Ballard using lava rocks for training

Ballard using lava rocks for training

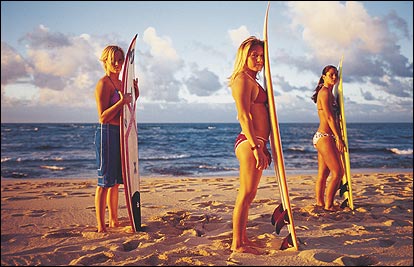

GO OUT TO ANY SPOT and you’ll notice stars who a decade ago were supporting players at best: women. Scores of females are paddling out to the breaks, and pro riders have amped things up with head-turning performances. Layne Beachley, 30, the four-time world champ from Sydney, Australia, is famous for taking on places like Oahu’s outer reefs and cracking her boards in two. Keala Kennelly, a 24-year-old from Kauai, along with the North Shore’s Rochelle Ballard, 31, and Woonona, Australia’s Kate Skarratt, 30, challenged the killer barrels at Oahu’s Pipeline on the movie screen in last summer’s Blue Crush, a go-for-it saga about one grommet’s quest to survive a women’s version of the famously dangerous Pipeline Masters competition. Now that the pro women have gotten good—really good—and the surfer girl image is cresting in pop culture, everyone from Hollywood producers to clothing manufacturers wants to ride the wave. But this time, the real surfer girls are determined to turn attention away from the beachside Gidgets and toward the athletes in the water.

“There are aggressive, powerful surfers on the tour,” says Kai Stearns, editor of SG: Snow Surf Skate Girl magazine. “They’re not just trying to surf as well as the guys—they’re getting inspiration from other women now.”

It all sounds so uplifting—a Wave of Their Own!—but there’s a depressing irony: Despite the groundswell of popular attention, women’s surfing at its highest level is experiencing serious problems. A movement to partially split the men’s and women’s tours has started to bonk, and lack of sponsorship has reduced the number of women’s events. At the end of December, when the women pros crown a world champion at Maui’s Honolua Bay, it may seem that Blue Crush was a little too far ahead of its moment. Not only have the women never had an event at Pipeline, they’re also failing to attract the attention that could make their sport an independent success.

A movement pushing for greater recognition for the wahines started back in 2000, when Ballard and fellow Women’s Championship Tour competitors Skarratt, Megan Abubo, Beachley, and Prue Jeffries established International Women’s Surfing, a group that lobbies to improve conditions on the tour. The IWC pushed the Association of Surfing Professionals, pro surfing’s governing body, to sanction more women-only events instead of piggybacking their competitions on top of the men’s, which usually take the lion’s share of exposure.

Though the effort resulted in one stand-alone women’s event in 2000, two in 2001, and three in 2002—as well as a doubling of prize purses, from $30,000 to $60,000—the apparent growth belies the fact that the women’s WCT has been unable to find sponsors. As a result, there will be only six WCT-level events for the women this year, as opposed to a dozen a decade ago. (There were 12 men’s events in 2002.) Only two companies, Roxy and Billabong, sponsor five of the six competitions during the season just ending, and the tour didn’t feature any events during most of October and all of November.

What’s the problem? If you ask the women, it’s the boys’ club mentality that has dominated the sport since the beginning. “We’re getting tons of exposure,” says Ballard. “But there are no new contests. The sponsors don’t think we deserve the money, and it’s bullshit.” Instead, money goes to surf models, like former amateur champ Veronica Kay, whose career took off after she posed for Maxim in 2001.

Of course, the sponsors are just following the money trail, and models in surf shorts reach more people than a competition in Fiji. “Fashion, surfwear, and lifestyle have exploded,” says Sam George, 46, editor of Surfer Magazine. “Where would you put your marketing money? It just makes sense—swimwear and surfwear marketing is a better return on your investment.”

Despite the setbacks, Ballard remains hopeful that women’s surfing will come out of the current slump. “The ASP has no plan for marketing their women surfers,” she says. “We want to go in the direction of mainstream sponsorship.”

The bright spot here is that the pros’ travails haven’t dampened the exploding popularity of women’s recreational surfing. Industry surveys show that since 1994 the percentage of female recreational surfers has grown from 5 to 18 percent of all surfers. Women’s surf schools are packed, and surf apparel company Quiksilver saw sales of its Roxy women’s line jump by more than 40 percent last year.

Ballard and the other pros don’t mind basking in the glow of the surf boom, but they also see it as a rare opportunity to raise the profile of their sport. “The mainstream has developed a crush on women’s surfing,” Ballard says. “Maybe it is more of a dream than a reality for girls to be able to surf in the Pipe-line Masters. But someday that dream will come true. I can’t stop pushing till it does.”