THE WAVES AREN’T BIG, but they’re long and glassy, and the women have them all to themselves. They trade off on slow lefts that break, one after another, off a sandy beach strewn with cobble and seaweed. Beyond the surf, the September ocean is smooth.

surfing Alaska

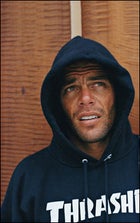

Nathan Fletcher

Nathan Fletchersurfing Alaska

The Santa Cruz boys at the airport bar: from left, Mulcoy, Max Schaff and Scott Sisamis from Vans, Rockhold, Smith, Loya, and Collins

The Santa Cruz boys at the airport bar: from left, Mulcoy, Max Schaff and Scott Sisamis from Vans, Rockhold, Smith, Loya, and Collinssurfing Alaska

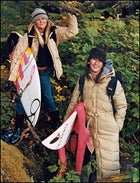

Mehlberg and Beachley, post-session

Mehlberg and Beachley, post-sessionThis spot wasn’t easy to reach; it took a full day of travel from Los Angeles on three separate flights, then this morning a local boatman shuttled us across the bay in a skiff. We carried the boards over the jungled isthmus of a tiny island to this beach, where the tail end of a swell is rolling in from across the Pacific.

But those trees lining the beach aren’t palms┬Śthey’re Sitka spruce. Out past the breakers, a salmon troller chugs by, and across the bay, wrapped in the clouds, stands North America’s third-highest peak, 18,008-foot Mount St. Elias. We’re a lot closer to the North Pole than the equator, which explains why six-time world-champion surfer Layne Beachley, perhaps for the first time in her 16-year career, came looking for waves this morning in an ankle-length parka.

Plunked down on the Gulf of Alaska 300 miles southeast of Anchorage, the fishing village of Yakutat (pop. 700) can’t be reached by road and gets ferry service just twice

They aren’t the only ones descending on Yakutat: Their first-ever-pro-female-surfers-in-Alaska mission is coinciding with the annual pilgrimage of another group of ten pro surfers, trailing an entourage of seven sponsors and cameramen. September is a good time to surf here, since it’s after the midsummer doldrums, but more important, because the silver salmon are running and you can fish and surf in the same place.

Yesterday, down at the tiny Yakutat airport┬Śa pair of rain-swept runways where a stuffed bear and a mounted moose head inhabit the parking-lot bar┬Śthe surfers were easy to spot amid the hunting and fishing camo. There was Beachley, wrapped in denim and turning heads as she floated across the terminal. There was Orange County recluse and big-wave seeker Nathan Fletcher, 30, bleary-eyed in a Thrasher sweatshirt. There were Reef McIntosh, a 26-year-old pro from Kauai, and three more Orange County riders: 14-year-old Ford Archbold, 18-year-old Erica Hosseini, and Jill Jacobs, 26. And arriving from Santa Cruz were Matt Rockhold, Jason “Ratboy” Collins, Josh Loya, Russell Smith, and Josh Mulcoy, a pack of pro freesurfers, aged 25 to 36, slouching from the luggage carousel in their tube socks and polka-dot shoes and cocked trucker hats, board bags in one hand and rod cases in the other.

Mulcoy, 35, is sort of the reason everyone is here: His pioneering expedition to Southeast Alaska in 1992 landed him on the cover of Surfer, dropping into a double-overhead barrel in front of snow-covered St. Elias. Ever since, a revolving roster of pro surfers has skipped the breaks of Fiji or Tahiti to come here each year, making a destination of this deep-woods, glaciated, and generally unlikely place.

The waves this morning aren’t the sort you’d travel the globe for, and air and water temperatures are both in the fifties. Still, there’s plenty to do. The photographers want some shots of the women huddled around a campfire in outfits provided by their sponsors. You know, real Alaska-looking stuff.

“I have trouble saying no,” Beachley tells me, then laughs. She’s a celebrity back home in Sydney┬Śshe dates the guitarist from INXS and gets chased down the sidewalk by paparazzi┬Śso she’s used to it. “If someone asked me to pose in the rain in a fucking bikini,” she says, “I’d probably say yes.” Her ensemble today, hot-pink cords and ditch boots, may be of questionable value for advertisers, but leaning over the fire with the wood smoke drying her hair, Beachley seems fairly content. She sits on the sand and looks out across the infinite icy ocean. Professional surfer or not, ultimately her reasons for making the long, chilly trek to the Gulf of Alaska are about the same as anyone’s: “I just had to see it,” she says.

NOBODY REALLY KNOWS how many waves go unsurfed in Alaska. The state has 33,000 miles of coastline, more than all the others put together. (California, the runner-up, has 1,100.) Much of that coast is either inaccessible, facing the wrong direction, or blocked from swells by islands and capes. But tiny Yakutat gets a straight shot from the Pacific in the form of relatively warm water┬Śup into the low sixties during summer┬Śthat arrives on the Kuroshio Current, the world’s second-largest after the Gulf Stream. Waves roll through here almost year-round. The islands and peninsulas that guard Yakutat Bay are like cogs, their nubs protruding in all directions; with a dozen or more point, beach, and reef breaks, if there’s any swell at all, it’ll be breaking at one of them.

That said, there are no guarantees. On Josh Loya’s first Alaska trip, in 1993, he and his friends were dropped off on an island by a floatplane. It rained the whole time, and the waves were lame. “Once we’d drunk all the whiskey,” Loya says, “we just sat around the rest of the week shooting guns at the campfire.”

Big waves or no, there is the sense of adventure in being the only one surfing them. On Mulcoy’s initial 1992 foray, the fishermen staying at the Glacier Bear Lodge thought he and his three fellow Surfer riders were nuts. “Every night when we got back to the lodge, they were amazed we were still alive,” he says. “They’d given us up for drowned.”

Since then, Mulcoy has been back more times than he can count. Why? “Just to sit in the water,” he told me. “Other places are beautiful, but I’ve never seen anything as dramatic as Mount St. Elias. It gives you peace of mind. And, besides, I don’t mind the cold. I like it, actually.”

Mulcoy and the others are a breed of pro surfer slightly different from world champs like Kelly Slater. Freesurfers don’t compete much┬Ś”not if I can help it,” says Mulcoy. Instead, they have sponsors┬ŚVans shoes, in this case┬Śthat send them around the globe to gather photos and videos. It might sound glamorous, but here in Yakutat the Vans junket means 15 guys and three girls wolfing down canned food in a pelt-laden three-story rental house called the Moose Mansion that might have been designed by Dr. Seuss and could, at any moment, tip over. Beachley, Bevilacqua, and Mehlberg have rented a separate, much tidier bungalow overlooking the bay, but the Moose Mansion stands on Yakutat’s main drag, right across from the liquor store. Someone got the idea to paint the thing green┬Śall of it: walls, eaves, porch, chimney, and the sheet-metal roof┬Śbut apparently the rain came and the painter gave up. Four rickety extension ladders lean up against its mostly green walls; outside, a roller floats in a pan of green rainwater.

There are not many streets in Yakutat, mainly just two intersecting strips of asphalt carved through the woods and lined with a smattering of lodges and shops (hardware, auto parts) and a bank housed in what appears to be a double-wide. Everything is wet. This week the town is as busy as it gets. It’s the height of silver salmon season, and all ten or so lodges are booked up. The entire fleet of dented rental vans is out bumping along the muddy roads, and the fish-cleaning station behind my room at the Glacier Bear Lodge buzzes late into the evening with packs of dudes in camouflage waders.

But the surfers are making cultural headway. Over the years, the town fathers have figured out that surfing could be big business, and now, in the person of Yakutat’s biggest surfing booster, 54-year-old Jack Endicott, they’re rolling out the red carpet. Endicott is the National Weather Service’s “official in charge” of the 230-mile stretch of coast from Cape Fairweather to Cape Suckling; he’s also a father of seven, head elder of the local Mormon ward, and owner of the Icy Waves Surf Shop, located in the back of his house. A self-described armchair surfer, he is a one-man welcoming committee, introducing the visitors to the local kids who’ve seen their pictures in magazines, supplying fish dinners from his own freezer, and predicting where the waves will be best.

With Endicott in the lead, the city council has passed a resolution in honor of Mulcoy and Beachley, proclaiming that surfing is a viable tourist industry. They’ve printed up the resolution on laminated yellow paper and thrown a party in somebody’s house with an open bar and a rustic buffet of salmon and black cod and even alligator meatballs flown in for the occasion by a Florida hunter who fishes up here every fall. Yakutat’s interim mayor, Casey Mapes, makes the presentation.

“Yakutat has great resources and cultures,” he begins, launching a speech that will go on for a while. Nathan Fletcher pulls out a cigarette and darts for the door. Mapes points out that while most tourists who come to Alaska take something away┬Śfish and game, mostly┬Śsurfers are showing that some leave the place just as they found it.

Whether or not the resolutions will find a place on Mulcoy’s and Beachley’s mantels, they accept them graciously. A player piano launches into some ragtime, and a few surfers scurry off to try the laser shooting range downstairs. Somewhere in the house a Chihuahua has been stepped on and lets out a scream. A second dog, a wet poodle, begins humping a stuffed orca and then pukes. It’s a hell of a party.

JUST AFTER DAWN one morning, Fletcher and I are bouncing down a dirt road in a big rented Chevy truck, looking for waves. The windshield is a web of cracks, and the heater doesn’t work, so we roll down the windows to defog.

Fletcher comes from a surf family: His father, Herbie, and his brother, Christian, were both pros. He quit the sport in the late nineties to pursue skateboarding and snowboarding, and when he came back to it a couple of years later, he started pulling never-before-seen aerial moves and towing in to Tahiti’s then-unknown monster break, Teahupoo. He rode with the Quiksilver team for a while, then abruptly quit. In a sport that markets the mythology of the brooding misfit, Fletcher comes across as an actual loner.

As I drive, he doesn’t talk about his family, his surfing, his sponsors, or anything else. We establish that we both live in trailers, his a double-wide in Orange County and mine a single-wide in Utah, and then we drive in silence, bumping across rocks and puddles to the slap-slap of the windshield wipers.

“How thick is that wetsuit?” I say.

“Thick.”

Nathan Fletcher is 30,

“Want a cigarette?” he says.

“Sure.”

We emerge from the forest and follow a sandy two-track out onto the beach.

“Eagle,” he says.

There on a gnarled stump is perched a bald eagle, its head the size of a softball. We watch it. We’re on a glassy bay, mist rising from the evergreens and glaciers off in the distance inching toward the sea. There are no waves, and when the rest of the surfers arrive in their beat-up rented Suburban, they decide to turn around and go fish for silvers off a bridge a few miles back. Ratboy and Rockhold own fishing boats back home, jigging for halibut when the waves are flat, and frankly don’t mind if the surf is no good. They’ve come to fish.

“Doesn’t anyone want to surf?” Fletcher mumbles, to no one.

Looks like no, so we drive on. The forest is thick, the puddles up past the hubs. Forty-five minutes later, when we finally reach a break that looks decent, Fletcher stares out at it for a long time. “I’m not as picky as some people about waves,” he says. These are a little more than head-high, fast and powerful and breaking on rock. I don’t want to go in, and Fletcher doesn’t want to paddle out alone. “Those guys have way better judgment than me,” he says.

Just when he decides to go back and convince someone to go with him, the others arrive. They’ve caught only one salmon and are ready to surf. In the lineup with Fletcher are Mulcoy, Loya, Ratboy, Smith, Rockhold, McIntosh, and Archbold. On the first wave, I watch someone disappear into a barrel for a three count, then emerge standing up. Guys launch aerials off the cold lips. Cruise ships steam by on the horizon. Fletcher gets out first, and by the time the others paddle to shore he’s already asleep, sitting upright in the truck, head pressed up against the window.

THE PLACE I’M LOOKING for is a few miles inland, in a settlement of weather-beaten boxes surrounded by hardy, aggressive spruce. After ringing a few wrong doorbells, I finally find the house, with surfboards leaning under the porch and the tiny sign that reads icy waves surf shop. I knock on the back door and Jack Endicott lets me in. With a white beard and a Hawaiian shirt over his belly, he looks like the Aloha Santa.

Endicott never envisioned himself as a surfer. “I made the mistake of taking the kids to Hawaii, and they fell in love with surfing,” he says. He’d moved to Yakutat back in 1980┬Śhaving already worked for the National Weather Service in Utah, Nebraska, and Alaska┬Śmet and married a local girl, converted to Mormonism, and started a family. Endicott quickly learned that outfitting seven teenagers with surfboards and wetsuits was going to break the bank, so in 1999 he opened the shop to buy the stuff wholesale. Six years later, he estimates that 400 visitors a year ring his hard-to-find doorbell, and while only about 50 of them are actual surfers, he and his wife, Laura, do a brisk business selling T-shirts heralding THE FAR NORTH SHORE.

But Endicott’s true passion is the weather. His mind is an almanac of swell direction, tide schedules, wind speed, and projected rainfall. “Man, isn’t this cool?” he says, clicking his mouse beneath a signed poster of Greg Noll dropping in at Waimea. He’s just discovered GoogleEarth, and he’s giving me a satellite tour of Yakutat’s surf spots. Because of unpredictable winds and because local tides can fluctuate by 16 feet, conditions change quickly.

“This one only breaks with a big southwest swell and a negative tide,” he says, pointing to a spot on the bay. He glances at his watch. “By the time you get out there it will be done. Tomorrow morning will be good, but by Tuesday it will be flat again.”

I thank him for the advice but don’t believe him. Yet when I get out to the driftwood-strewn beach a half-hour later, I see I should have listened. The water where the waves are supposed to be is as flat as a mirror. The next day, when I hit it precisely at low tide, it’s just as he predicted. There’s a lone guy surfing┬Śhe tells me that whenever a good swell hits, he cashes in frequent-flier miles and comes over from Juneau. I don’t know if he qualifies as a local, but I’ve never been so welcomed at anyone else’s surf spot.

“It’s good to see somebody else in the water,” he says. “I get used to being the only one out.”

We surf together, set after set rolling through. The beach is contained by thick forest, and out across the bay the fog lifts just enough to show the toe of a glacier cracking off the snowy base of St. Elias. Let me repeat that: I’m surfing incredible waves within sight of a glacier. The water numbs my fingers and face, but after a while it doesn’t seem all that cold┬Śnothing worse than Northern California, anyway. The waves rise out of nowhere, glassy peeling lefts we ride a few hundred yards, all the way to shore. After an hour, the tide rushes in so fast that you can watch it climb the beach, and as quickly as the waves arrived they disappear, leaving the spruce-ringed inlet once again calm, gillnetters pushing toward the open sea.

THERE’S A PARTY at the Moose Mansion. Rockhold and Ratboy are grilling fish, and they’ve invited Beachley, Mehlberg, and Bevilacqua over. A stack of salmon fillets from the day’s catch rise up on the Formica beside the halibut steaks contributed from Endicott’s personal stash. The TV is on, Reed and Russell are playing foosball, and Ford Archbold lies cocooned on the floor in a shimmering silver board bag. A big ling cod is curled in a plastic tub by the front door. A commercial comes on starring Andy Irons, the world-champion surfer. It’s a fast-food ad, and he’s talking to an infant he calls “the Big Kahuna.”

“You’ve got to be fucking kidding me,” someone says.

One of the surfers flips to a channel showing mild pornography. The guests arrive. If anyone thinks a good way to accommodate female dinner guests is to turn off the porn, they don’t say so. Rockhold piles the buttery fish steaks on a plate beside a pot of instant mashed potatoes and a pan of grilled vegetables. Everyone lines up with a plate, and we sit around the TV and eat. People are tired and planning to get up early and surf.

Afterwards, Fletcher, Smith, Rockhold, and I head over to the bar at Glacier Bear Lodge. It’s ladies’ night, though not many have shown up. Fishermen are shooting pool. A few drunks are on the dance floor. CNN flickers from a wide-screen.

Fletcher is silent, nursing a Sprite. I ask him what he did today.

“Surfed a bit. Laid around. Looked at the wall.”

Then a guy sits down beside him and introduces himself. He’s a local, a surfer, a commercial fisherman, and a helicopter pilot. He’s flown up and down the coast in a seaplane. He’s seen a lot of waves. Fletcher perks up. The guy knows of a volcanic island that he thinks could hold a 20-foot swell. A gentle slope of volcanic debris forms the island’s beach, which translates to backdoor barrels, never before surfed. Fletcher emerges from his hood, eyes flashing. He leans over and slaps Smith on the hand. “Listen to what this guy’s saying.”

Smith moves closer while the guy talks. He needs no convincing. “Let’s do it,” he says.

“Let him finish,” says Fletcher.

Smith’s mind is racing with logistical details. He wants to know what kind of boat, what kind of plane, what time of year, how far away. If Alaska is surfing’s last frontier, Yakutat is just the gateway. Who knows what else is out there?

“Let him finish,” Fletcher repeats. The Budweiser sign is blinking overhead. Fletcher leans in intently, but his eyes are serene and distant, his mind 3,000 miles to the southwest, where a tropical storm is whipping up a swell and pumping it north, until one fine day it will collide with this jagged volcanic shore. He can see it already.

“Now,” he says, turning to the Alaskan. “Tell us about that island.”