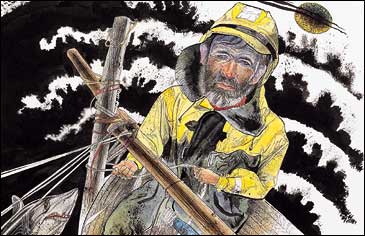

AN ICY WAVE CRASHES DOWN into the open boat. The four cramped, wool-clad seamen are bailing desperately, yet faithfully as monks. Trapped in a gale, sailing west between Iceland and Greenland, they have scarcely slept in 36 hours. They’re stunned by prolonged hypothermia and weak with exhaustion, and spirit alone is keeping them alive. That and the unlikely hardiness of their craft, the 36-foot Brendan, a twin-masted Irish curragh featuring the latest sixth-century design and materials. Built to flex like a sea serpent and thereby absorb an ocean flogging, the hull was hand-stitched from 49 ox hides, each a quarter-inch thick, waterproofed with wool grease, and stretched over a 36-foot rib cage of Irish white ash. Nearly two miles of leather thongs bind the traditional frame together.

Another wave curls high over the leather boat and explodes down upon the sailors, knocking them off their feet. They are knee-deep in gelid gray water, with food and clothing, skinned seagulls and whale blubber, sheepskins and oilskins—the ancient flotsam of death at sea—sloshing about them. Thick tarps, stretched gunwale to gunwale, deck three-quarters of the Brendan, but where the helmsman must stand there is a gaping hole. If it is not covered, the boat will founder in this tempest, and the ocean will summarily swallow the sailors and their dream.

The captain suddenly recalls the spare ox hides stowed aboard to patch a potential tear from icebergs. In the midst of the gale, the hides, stiff as war shields, are dragged out, perforated with a knife, and lashed together. The makeshift shell is mounted over the gap. The helmsman must now stand in a small porthole, fingers frozen stiff as wood—but the boat stops sinking.

In time, the storm, unsuccessful at killing the sailors, thunders away, and fog settles upon the cold sea. Like a ghost ship, the curragh floats onward, into the maze of icebergs off the east coast of Greenland.

ACCORDING TO LEGEND, Saint Brendan sailed from Ireland to Newfoundland 1,400 years ago, but the expedition described above took place in the late 20th century, led by a heretical explorer named Tim Severin.

“There’s no question that the Brendan voyage was my most dangerous journey,” says Severin, speaking so softly my tape recorder barely picks up his voice. “The margins were very slim. It set the threshold for fear. Once you’ve been really, really scared and then you come through and everything’s fine at the end, it’s very difficult to get as frightened again.”

Severin and I are having lunch at the Casino House, in the quiet hills of County Cork, Ireland, Severin’s home for more than 30 years. A slight 63-year-old man with blue-green eyes, a lean, handsome face, and a thin neck wrapped in a paisley cravat, Severin looks more like a distinguished British intellectual than one of the finest modern adventurers. In truth, he is both: recipient of the prestigious Founder’s Medal of the Royal Geographical Society as well as the Livingstone Medal of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society, author of 15 books, winner of numerous literary awards, and the only man to have built and sailed five different seagoing vessels of ancient design.

In an age when stunts of extraordinary physical skill are regularly performed with little apparent purpose beyond 15 minutes of fame—hucking 100-foot waterfalls, snowboarding Everest—and the risks transparently outweigh lasting value, Tim Severin is an adventurer cut from a different cloth.

“No one’s tried another Brendan voyage, and my advice is, don’t,” Severin says, laughing. “It’s like a doctor who injects himself with some sort of unknown drug. The hypothesis has been tested. Further risk is unwarranted.” Severin’s 1976–77 Brendan expedition became his benchmark for exhaustive research and methodical preparation. Studying the eighth-century Latin text Navigatio Sancti Brendani Abbatis, which describes a precise if phantasmagoric voyage to the New World by Saint Brendan, a sixth-century Irish monk and missionary, Severin began to believe that such a journey may have actually taken place.

The only way to prove it was to do it, so he did. He spent two years building a replica of the early Irish skin boat, then, using the Navigatio as a travel guide, sailed the craft 4,500 miles from Ireland to Newfoundland via the Hebrides, the Faroe Islands, and Iceland. Though he nearly died trying, Severin proved that seafaring Irish monks could have discovered North America in the sixth century, well ahead of the Vikings and almost a millennium before Columbus.

In 1978, Severin’s account of the journey, The Brendan Voyage: An Epic Crossing of the Atlantic by Leather Boat, became a global bestseller, was translated into 27 languages, and established Severin as Thor Heyerdahl’s rightful successor.

EVEN BEFORE TOUCHING in the Brendan, Severin was dreaming of his next project: retracing the route of perhaps the greatest literary seafarer of all time, Sinbad the Sailor. In 1980–81, Severin built a medieval ship and sailed the 6,000-mile great trade route described in The Arabian Nights, from Oman, on the Arabian Peninsula, to Canton, China.

In 1984, he designed a 20-oar galley to exact Bronze Age specifications and, with a 17-person crew, rowed it from Greece to the Soviet republic of Georgia, proving that the Greek myth of Jason and his quest for the Golden Fleece was based on geographical fact. The next year, Severin used the same boat to tackle the über-myth of Western literature, retracing Ulysses’ odyssey from Troy to Ithaca. Following that, he completed two overland expeditions by horse, one tracking the 2,500-mile route of the First Crusade across Europe, the other exploring the Mongolia of Genghis Khan; two more sea passages, the China Voyage and the Spice Islands Voyage; followed by two expeditions searching for the historical roots of Moby Dick and Robinson Crusoe.

Severin wrote a book about every expedition he completed. All told, he devoted between two and four years to each project, using the book contracts to fund his unorthodox life of adventure and creating a bankable franchise of historic reenactment. To connoisseurs of British sailing literature, Severin the author is legendary. However, unlike much contemporary travel writing, his work is free of emotional outpourings. He is eloquent at description, fastidious about mythic details, but reticent about his personal life. (He was married for ten years, then divorced, and has a grown daughter named Ida.) Much like the 19th-century English explorers, Severin keeps his own counsel and sticks to facts. No confessional effusion, no dark psychological secrets, no wanking.

Reading his books, you realize that Severin is an anachronism: Rigorously disciplined, he is willing to go back in history and re-create the conditions and crafts of ancient travelers, and then physically experience their difficult journeys himself, risking his life to better understand the complex intertwining of history, myth, and geography.

Severin, in short, is a time traveler.

BORN IN ASSAM, India, in 1940, Severin credits his upbringing for igniting his exploratory instincts. His father was an English tea planter born in South Africa; his mother, half British, half Danish, was born in India. At the age of six, Severin was shipped off, like so many children of expats, to boarding school in England.

“Look, this was ordinary,” says Severin. “It made us extremely independent and self-sufficient at a very early age. We could cope perfectly well, thank you very much. No need to be led by the hand.

“I spent my holidays in England with my grandmother, who had spent her entire life in India. Everything in the household, all the photographs on the walls, all the reference books, all the literature, came from India. I grew up with this whole mythology around me.”

Severin was educated at Oxford, where he received a graduate degree in medieval Asian exploration. Researching his thesis, he and two companions retraced the route of Marco Polo, from Venice to Afghanistan, by motorcycle, a journey that resulted in his first book, Tracking Marco Polo (1964). It also foreshadowed his lifelong obsession with epic voyages, and the lengths to which he’d go to achieve historical accuracy.

Building Sinbad’s ship, a 90-foot motorless vessel with 2,900 square feet of sail, required 140 tons of hardwood Severin hand-selected in the forests of India, 50,000 coconut husks that were spun into 400 miles of coconut rope to bind the hull planks and ribs together, and 20 traditional shipwrights working nonstop for 165 days. In November 1980, Severin launched the Sohar—named after the ancient Arabian port and purported home of Sinbad—sailing from Muscat, Oman, bound for China.

During the seven-and-a-half-month voyage, Severin and his sailors endured many of the struggles early Arab seamen—the prototypes for Sinbad’s character—must have faced. They shared quarters with all kinds of creatures: fruit flies that burrowed into their nostrils, a plague of cockroaches that skittered over their faces, mice in the food lockers, rats in the bilge.

Then there were the mind-warping doldrums. On the 900-mile crossing of the Indian Ocean, from Sri Lanka to Sumatra, the ship began sailing backwards in a headwind. Soon the Sohar was stranded at sea.

“We were facing the long, slow, gnawing doubts of boredom, frustration, and the ultimate possibility of thirst,” wrote Severin in The Sindbad Voyage. “We had truly moved back into the days of sail on ocean passages. Our time scale was longer, slower, and ultimately dependent on nature.”

For the next 35 days, the Sohar zigzagged aimlessly in the middle of the sea. As food and water began to dwindle, the 27-man crew became resourceful. They fished constantly, but instead of eating their catch, they used it as bait to hook sharks for food. Once they managed to bring in 17 sharks in just ten minutes. During storms, they rigged canvas tarps under the mainsail, funneled the rainwater into buckets, and then passed them hand to hand to the ship’s cistern.

“Patience is very easy to display,” Severin explains when I ask him about his cool stoicism, a rare quality in this age of instant gratification. “If you believe what you’re doing is something truly worthwhile, you stay with it. Frustration arises when you think what you’re doing is empty and useless. If the project is worth doing in the first place, it’s worth being patient about.”

And what makes a project worthy? For him, Severin says, there are two inflexible criteria:

“First, it must be original—something that no one has ever done before. Second, it must stand a reasonable chance of advancing knowledge.”

Just days after escaping the doldrums, an abrupt, violent shift in wind slammed the mainsail against the mast and broke the foot-thick, 81-foot main spar in two. “Sohar had been crippled as effectively as a butcher snapping the leg bone of a chicken by twisting it against the socket,” Severin wrote. They were 450 miles from Sumatra. Improvisation in times of calamity is one of the defining characteristics of great adventurers, and Severin immediately put a plan into action. Within seven hours, the crew had salvaged the long section of the broken main spar, smoothed off the fractured end, and rigged it with a spare mizzen sail, and Sohar was once again “moving briskly through the water.”

Intriguingly, although Severin has managed to display equanimity in the face of countless dangers over four decades of exploration, none of his books address the issue of courage.

“I don’t see my journeys as tests of courage,” he explains, “but more as tests of knowledge. When I select a project, I examine the evidence. I search for the kernel of truth within the legend. Could a ship of that kind have made such a journey? I gather information, do my homework, dig. If, after a year of research, the project still seems worthy, I build a boat as true to the original craft as possible, then we go out and do it. You get into heavy weather and there are some fraught moments, but I’ve done the calculations and think the risks are acceptable. There’s no courage involved.”

ALTHOUGH HE HAS HAD more than 200 teammates over the course of 15 expeditions, Severin has never lost a single man—perhaps the truest testament to his leadership.

“Severin has a deep sense of responsibility for his crew members,” Joe Beynon told me from his home in Switzerland. The coordinator for health and detention at the International Committee of the Red Cross, in Geneva, Beynon, 39, crewed on and photographed Severin’s 1993 China Voyage, a test of whether the Chinese could have crossed the Pacific 2,000 years ago in a bamboo raft. Three years later, he rejoined Severin for the 1996 Spice Islands trip, which retraced the route of Alfred Russel Wallace, a 19th-century naturalist who recognized the possibility of natural selection before Darwin.

“Tim’s very up-front about the risks and wants to bring people back safe and well,” Beynon continued. “It’s never a question of people dying. He sails original ships, minimizes the risk, and you all go home safely. Tim’s very meticulous at planning, very workmanlike, and leaves nothing to chance.”

Thinking of all the trips I’ve been on where conflict has blown the team—and sometimes the expedition—completely apart, I ask Severin how many people have dropped out of his projects.

“Two, maybe three; all the others were really first-rate,” he says cheerfully. “People seem to rise to the occasion—they do more than cope; they learn, they make a great contribution. I’m a big believer that almost anyone can handle a remote journey.”

So what is the most valuable characteristic of a good teammate? Bravery, stamina, technical skill?

Severin grins. “I would say being laid-back, easygoing.”

“With Tim, there’s no rush, no desperation,” said Murdo McDonald, 35, a geography teacher from the Outer Hebrides who accompanied Severin on his most recent project, a search for the sources of the fictional character Robinson Crusoe. “Tim takes time to understand a culture. He doesn’t have a predefined idea of where the end will be or what he’ll find. He goes slowly, conscientiously, and lets things unfold.

“It’s all about the myths and legends for Tim. If nobody in the world knew about his projects, but he could still do them—why, he’d still be happy.”

Most telling of all, both Beynon and McDonald added that if Severin were to call today, they’d both drop everything to go with him.

NANSEN, AMUNDSEN, Shackleton, Hillary. I put Severin in this elite company of great adventurers who have left a meaningful legacy. Not for his skill at re-creating ancient vessels, nor for his ability as a captain at sea, not even for so thoroughly succeeding in his vast ocean voyages, but rather for his incisive interpretations of some of the greatest literature of humankind.

Upon reaching Sumatra on the Sinbad Voyage, Severin was able to connect the original tales of cannibalistic tribes that fed their victims drugged food to modern tribes that still use the island’s marijuana in their cooking.

In retracing Wallace’s journey through the Spice Islands of Indonesia, Severin resurrected one of the most unheralded evolutionary theorists of all time, filling in the biographical blanks that no professor scouring libraries ever could.

And in his most recent book, In Search of Robinson Crusoe (2002), Severin discovers that an obscure runaway white slave named Henry Pitman, who was once marooned on an island in the Caribbean, may have provided Daniel Defoe with his prototype for Robinson Crusoe, much more than the infamous Scotsman Alexander Selkirk did.

When I list these examples for Severin, he is visibly pleased but says nothing. For several minutes his eyes stare right through me, as if he were out upon the ocean. Then he grins and his whole face lights up.

“From the first book I wrote, my editors have said, ‘Put more of yourself into it.’ And my response has always been: No. It’s not about me. The book is about the project, the ideas.” So what is Severin’s next adventure? He refuses to say.

“I much prefer to do it first, then talk about it.”