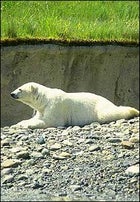

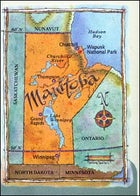

CHURCHILL, MANITOBA, ATINRY PORT TOWN perched on the western edge of the Hudson Bay some 600 miles north of Winnipeg, bills itself the “Polar Bear Capital of the World.” And rightfully so. Each fall, hundreds of the white-furred beasts, and the thousands of tourists who come to see them, converge on this hardscrabble Canadian outpost and its 1,000 human residents. Growing up in Winnipeg, I’d heard about the bears and about Churchill’s rough side—the dockhand life, the visiting Soviet freighters and their hard-drinking crews. Only later did I find out about the natural beauty, and about Churchill’s long history as a crossroads of humans, animals, and ecosystems. It’s a place where native Cree longshoremen help Korean sailors load grain in the seaport and caribou and red foxes roam the tundra and taiga.

Tread lightly: Churchill’s fragile, technicolor tundra

Tread lightly: Churchill’s fragile, technicolor tundra In late spring and summer, you won’t find many polar bears—the icebreak deposits them farther down the coastline—or, consequently, many other visitors. What you will encounter are nearly 200 species of birds, including snow geese and eider ducks, in one of the Northern Hemisphere’s key flyways; flowering tundra; and pods of beluga whales—no shortage of thrill-seeking in Churchill while the bears are away.

Exploring Wapusk National Park

I’m here for a week to explore Churchill without its famous blanket of white. I get a good start the morning after I arrive, when I hitch a helicopter ride to Wapusk National Park, 35 miles southeast of town. Wapusk—nearly 4,500 square miles—is one of North America’s wildest places. From my hovering perch, I can see where the treeless tundra morphs into taiga—a thin boreal forest of stunted conifers, muskeg, ponds, and rivers. In Wapusk you could see an Arctic fox and a red fox, a ptarmigan and a spruce grouse, a caribou and a wolf, a polar bear and even the odd grizzly—all in one day.

But in the three and a half years since its founding, only a handful of people have visited. The reason? Wapusk (which means “white bear” in Cree) may be the most concentrated polar bear denning area anywhere; on average, one in three overnight visitors—of only about 200 per year—has an aggressive encounter. (A future general park plan, tentatively slated for summer 2001, could increase the number of outfitted trips to the park.)

So you might think twice about camping here, but provided you plan your trip carefully—namely, with the guidance of the park’s chief warden, Doug Clark—Wapusk is ripe for adventure. In early June, when the bears are still out on iced-over Hudson Bay, you can canoe the Class II-III, spruce-and-tamarack-fringed Owl River, where you’re likely to see kingfishers, wolverines, moose, and in its easternmost reaches, the occasional harbor seal. Or if you heli-hike the coastline, according to Clark, “caribou will walk right alongside you because they’ve never seen a human.”

I certainly didn’t see anyone when I was there.

Subarctic Snorkeling in Hudson Bay

Hudson Bay belugas

Hudson Bay belugasNow’s a good time, whispers my guide, Barbara Draper, a Winnipeg native who’s lived and worked in Churchill for the last decade. She smiles—perhaps a little too enthusiastically—as I brace myself for the 38-degree-Fahrenheit water. I clamp my snorkel onto my mask and slip over the side of the Zodiac in my titanium-lined, blubberesque wetsuit, tow rope in hand. Barbara revs up the boat and slowly accelerates, with me trailing face down.

As I’m towed—we’re hoping the boat’s movement will attract a nearby pod of whales for me to see—the ice-chilled waters of Hudson Bay torturously infiltrate my wetsuit. Small wonder, I muse, that each season only a few twisted souls give this a whirl.

First I hear them: Their calls range from whistling tea kettles to chattering monkeys to squealing tires—kind of like several Hollywood sound-effect CDs all at once. Yet I see nothing but a gray-green gloom. Then a plump torpedo of radiant white, maybe 14 feet long, shoots up from the depths on its back. In seconds a beluga is beneath me, close enough to make eye contact before it dives out of sight. Moments later a second beluga coyly approaches, veering away when yet another joins in.

For two hours we carry on, me and dozens of belugas from different pods, including a handful of slate-colored calves. When I finally flop back into the Zodiac, the cold water has frozen my mouth into a permagrin.

Tundra-Trekking Cape Churchill

Ten minutes east of town, my companion and guide Paul Ratson, a tundraman from central casting, looking swarthy in a rust-colored flannel shirt, pulls his weathered van off the road and, as a matter of course, grabs his pachyderm-stopping .375 rifle.

We’re here in Cape Churchill Wildlife Management Area for a morning trek from the wreck of a cargo airplane that crashed in 1979 just off the coastal road to the shore of Hudson Bay. As we head out, the flat, rocky vista looks benign, if not boring. It dawns on me that the terrain’s subtleties demand an attentive eye. I squat and rest my palm beside a tiny flowering oyster plant. The tundra, which at first seemed dull, even desolate, is actually a finely woven carpet of lichen, peat moss, and plants in bloom, laid between stone and boulder. We try to walk weightlessly across the fragile, technicolor moonscape so as not to leave our Vibram-patterned footsteps for a millennium’s time.

Reaching the water’s edge, we give wide berth to a recently killed whale, keeping our boots clean of its dangerously bear-enticing scent. I ask Paul how he spends his holidays, expecting to hear about the usual trip to Florida.

“I go further north.” A man in his element.

And why, years ago, did he come up for a visit and end up staying? “Just look around.”

Out in the bay, a pod of arched white backs cuts through sunlit water. Beyond the point lies the Ithaca, a huge rusting freighter grounded in a 1961 storm, a reminder of just who has the final word up here.

It’s answer enough. It really is.

Thawed beauty. But still, beware the summer cold.

Churchill during bear season can seem as crowded as New Orleans during Mardi Gras (just don’t sleep in a doorway). The rest of the year the vibe is much calmer, but it’s still essential to book lodging and activities early. July and August are the only months you don’t need to pack serious winter garb; even then, days can be cool and nights near freezing.

GETTING THERE: Other than by freighter or dogsled, the only way to Churchill is by plane or train. Canadian Airlines (800-426-7000) flies to Churchill from Winnipeg, with round-trip fares starting at $425. The train ride from Winnipeg is 36 hours each way on Via Rail (888-842-7245); fares start at $189 round-trip.

ACCOMMODATIONS: The Churchill Chamber of Commerce (888-389-2327) can connect you with the town’s handful of utilitarian hotels—I stayed at the clean, friendly Polar Inn ($69, double occupancy; 204-675-8878)—and B&Bs (starting at $58, double occupancy).

OUTFITTERS: Sea North Tours (204-675-2195) runs beluga-spying snorkeling trips for $112 per hour. It’s BYO wetsuit: One Stop Diving in Winnipeg (204-257-2822) rents toasty seven-millimeter titanium-lined suits with hoods, gloves, and booties for $80 per week. Paul Ratson’s ���ϳԹ��� Walking Tours (204-675-2147) offers tundra treks (starting at $36 for a half day). Churchill-based Hudson Bay Helicopters (204-675-8823) does drop-offs and pickups in Wapusk National Park (no park fee, contact warden prior to your arrival; 204-675-8863) for $575 per hour for groups of up to four.