Five years ago, Brad van Liew, a 29-year-old commercial pilot and flight instructor from Southern California, took a bit of a flier by entering the 1998-1999 Around Alone, the single-handed around-the-world yacht race generally considered to be the longest event in sports. Despite a lack of experience and an old boat, he battled his way to a creditable third place in Class II for boats 50 feet and under.

This time around, Van Liew, now 34, simply ran away with the race, posting horizon-job victories over his Class II rivals in each of the race’s five legs and occasionally even besting some of the more powerful 60-foot Class I yachts. He finished the fifth and final leg of the 2002-03 Around Alone at 5:53 A.M. local time Sunday morning, becoming the first American to win a solo, around-the-world race since Mike Plant won the 1986-87 edition of the same race. Van Liew sailed more than 32,000 nautical miles in a total elapsed time of 148 days, 17 hours, 55 minutes and 42 seconds.

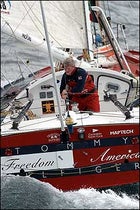

There are no cash prizes for Around Alone winners—as Van Liew’s wife Meaghan explains, “Just knowing you did it is enough”—and not much in the way of media attention, either. Still, you can expect to see a lot more of his all-American mug, as well as those of Meaghan and infant daughter Tate, this autumn. All three, along with van Liew’s star-spangled boat, Tommy Hilfiger Freedom America, figure prominently in the jeans maker’s marketing plans for a nautically-inspired fall fashion line.

���ϳԹ��� contributing editor Rob Buchanan chatted with Van Liew on Friday via satellite telephone, as the skipper neared the finish line of the Around Alone’s fifth and final leg in Newport, Rhode Island.

���ϳԹ���:

Where are you right now?

Van Liew:

Pretty much exactly 300 miles south of Newport.

How’s the weather?

It’s blowing about 25 to 30 and fairly rough, though I just got out of the Gulf Stream so it’s not as rough as it was a little while ago. There’s a pretty good storm up ahead and I’m trying to sail as east as I can at the moment, to get on the other side of it. Basically the low’s gonna come right over the top of me. Then I should have northeasterlies which could allow me to finish tomorrow night. If I don’t get through and get the northwesterlies instead, it’ll be Sunday morning.

How are you feeling physically?

Pretty good, pretty strong. I’ve lost a lot of weight since the race started— probably 25 pounds. I need to get out on my motorcycle and ride around in the desert, do some hiking, get my legs going again. But hey, it’s a healthy lifestyle out here.

What about sleep? Aren’t you a wreck after nine months of catnapping?

Not really. I almost think I could do it indefinitely. When I start a leg I don’t even think about sleep for the first 48 hours—too excited. Later you start looking for opportunities to sneak a quick nap, and now I’m fatigued enough to put my head down just about anywhere for ten minutes. But with the finish coming up, that’s impossible. Newport can be a tricky landfall, and there’s a ton of shipping out here…I’m sure I’ll be pretty shagged by the time I get there.

Any particularly scary moments on this leg?

Not yet! But then again, it’s not the Southern Ocean. It’s a very tactical leg with a lot of different weather patterns, but there hasn’t been a whole lot of crash and bang type stuff. Really our only heavy weather this whole leg was…well, today.

Let’s go back to your early days in this sport— who got you into it?

Mike Plant without a doubt was my most heartfelt mentor. I miss him. He was a very different personality than me, and the sport was different, too, ten years ago. He was more of an adventurer. The new breed is very precise and calculating, to the point where the sport has almost become a science. Guys are racing with monitors to maximize the efficiency of their sleep patterns, calculating onboard weight down to the ounce, that kind of thing. The sport just isn’t about voyaging anymore—it’s a serious racing environment.

What makes you so good at it?

I’m not the best anything on a boat. I’m not the best navigator or the best maintenance guy or the best sail trimmer. But I’m pretty good at every one of those, kind of a jack of all trades. That’s just the mechanical part of it, of course—the easy stuff. The hard part, the part nobody knows until you get out there and do enough miles to get your head around it, is the mental aspect. You’re either able to keep the whole house of cards together, or you’re not.

Ever felt yourself beginning to lose it?

In the 1998-99 race, leaving Punta del Este, Uruguay and about a day and a half into Leg Four, I almost did. I was still in the Rio Plata, it was blowing about forty out of the north and the current was doing about three out of the south and it was a nasty, choppy situation. We were pounding to windward and suddenly, bang, I lost the rig—dismasted. I think it had been compromised about two days before Cape Horn when I rolled the boat upside down.

Emotionally, it was really tough. We were three quarters of the way around the world and I was less than nine hours behind the guy in front of me—it was an elapsed time race then, not a point system like now. I really wanted to win the last leg and be the first boat home to the U.S., which would have been huge for me, and I think it was possible—my boat was old, but it was good in light air and upwind. It was the only leg I had a prayer in, and I knew I was going to be pushing super, super hard.

Mentally, it was just shattering. It was the one leg where I was like, ‘Screw the adventure, I’m here to try to beat this guy.’ And so I had a mind melt when it happened. Most of the credit for me even finishing that race should go to Meaghan. I called her on the satellite phone when the rig went down and said, ‘Well, that’s it, we’re out of the race.’ She said, ‘I’ll be damned if we’ve gotten this far, and you don’t finish this thing.’ She was right. If I hadn’t jury-rigged a sail, and just turned on the motor instead, I would have been disqualified. She got a team together and a bunch of shore crew from the other boats stayed to help me re-rig. I lost nine days but was able to hang on to third place by passing a few of the tail enders on the way north.

How about this race—any meltdowns?

No, but it’s been tough for me to monitor my frustration levels. When I’m sailing I’m really competitive and super focussed, not introspective or philosophical. I can get ticked off, really angry at myself, if I’m doing badly. I need to learn how to chill out and give myself a few moments, force myself to relax.

Any particular techniques for that?

I try to set up a routine that puts a little bit of a priority on having a human lifestyle. I try to have a glass of wine most nights, and every few days I’ll actually spend the time to make a little meal on my one-burner camp stove, you know, actually making up a pasta sauce instead of just straight freeze-dried. I also take a few books, maybe four on each leg, and I might read a chapter.

Have you ever gotten through all four?

[Laughs] Uh, not quite.

Leg Four took you across the Southern Ocean and around Cape Horn—your second rounding. Do you buy that ‘sailor’s Everest’ line?’

I used to be like, ‘No, the whole thing for me is my Everest, and Cape Horn’s just another switchback in the trail.’ But when you get there it’s like, ‘Whoa, this really is pretty amazing.’ You live with such a knot in your stomach the whole time you’re doing the Southern Ocean thing. You’re just so far from home, dodging ice and the whole thing, and man, when you get to turn north and get back in the Atlantic it’s like, ‘Oh, wow, now it’s just a sprint to the finish.’ [Laughs] Even though it’s not.

What’s the most dangerous thing about single-handing?

One is an injury or a sickness that you can’t deal with yourself, like appendicitis or a broken arm or leg. But probably the scariest thing is becoming separated from your boat. Getting in a life raft if it goes down, or worse, falling overboard and watching it sail over the horizon. It’s definitely something that gives you cold sweats every time you think about it, so you wear a harness and try to limit the risk.

Some people say single-handed racing will never catch on in the U.S. — our sports menu is too crowded.

That’s a really myopic, self-centered view, which is typical of the American persona. If you look at Europe, single-handed racing is without a doubt the largest, fastest growing sponsorship sport there is. Obviously the America’s Cup has more money being thrown at it, but it’s a massive waste and companies know it, which is why companies don’t do it anymore—it’s just the playground for the mega-rich. Open Class boats [the ultra-wide 50- and 60-foot skimming dishes used in the Around Alone] have been specifically designed to cater to a lot of needs: crewed round-the-Atlantic races, single- and double-handed trans-Atlantics, and single-handed around-the-world racing.

So you’re not worried about the health of your sport at all?

I guarantee you that in 20 years you and I are gonna be sitting here having a beer and laughing about how absurdly huge the sport has gotten.

What about your own future—are you going to do another one of these?

I’m not sure I’m up for soloing the Southern Ocean again. Having a baby changes a lot of things, and this sport is pretty extreme—a bit like playing Russian roulette. I’m gonna stay involved in it, do some crewed events as opposed to solos, maybe consult for other people. As long as we have a plan in place where I can afford the lifestyle that I want and I feel good about what I’m doing, I’ll be fine. If not, maybe I’ll get back into flying. I was just thinking the other day about buying a [Cessna] 185 with skis on it, and maybe doing a little Antarctic expedition….