“TWO SAILS, DEAD AHEAD,” helicopter pilot Marty White says over the intercom. “And two more towards Auckland.” White, 31, is a beefy, cool-talking Kiwi who has logged many hours on risky mountain-transport operations, and our preflight safety briefing was short and simple. “Don’t let anything fly out the open doors,” he drawled, glancing at our loose photographic gear. “You might take out the tail rotor.”

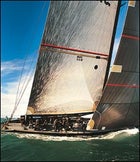

Stars and Stripes: With Ken Read at the helm, Team Dennis Conner launches into a practice race.

Stars and Stripes: With Ken Read at the helm, Team Dennis Conner launches into a practice race. The stealth yacht's of Oracle BMW Racing in New Zealand's Hauraki Gulf.

The stealth yacht's of Oracle BMW Racing in New Zealand's Hauraki Gulf. Return to spender: Oracle BMW Racing boss Larry Ellison says he intends to log some serious cup time at the helm.

Return to spender: Oracle BMW Racing boss Larry Ellison says he intends to log some serious cup time at the helm. Cloak and rudder: Oracle BMW Racing drapes one of its yachts in heavy skirts before lifting it from the water.

Cloak and rudder: Oracle BMW Racing drapes one of its yachts in heavy skirts before lifting it from the water. Kiwi Russell Coutts jumped ship from Team New Zealand to sail for the Swiss.

Kiwi Russell Coutts jumped ship from Team New Zealand to sail for the Swiss. High-tech tack: computers aboard Sweden’s Victory Challenge reveal perfect wind angle speed.

High-tech tack: computers aboard Sweden’s Victory Challenge reveal perfect wind angle speed. Unloading the sails for the day.

Unloading the sails for the day. Eternal vigilance: Team Victory Challenge electronics specialist Peter Tans (left) and grinder Kasper Vang keep watch on a practice run.

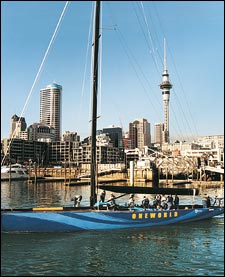

Eternal vigilance: Team Victory Challenge electronics specialist Peter Tans (left) and grinder Kasper Vang keep watch on a practice run. What million buys: A Oneworld Challenge yacht heads to sea.

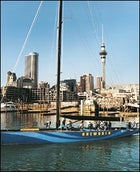

What million buys: A Oneworld Challenge yacht heads to sea.

Cruising high above New Zealand’s Hauraki Gulf, a 40-mile circle of sparkling green water near Auckland, you see a sweeping South Pacific panorama that stretches from the city’s glistening office towers to the lush Whangaparaoa Peninsula in the north. But we’re not playing tourist on this July afternoon, in the dead of the New Zealand winter. We’re on a recon mission to check out the nautical hardware that’s being tuned up for the most competitive and expensive race on water: the 31st America’s Cup. From a thousand feet up, it’s easy to spot the sleek racing machines that we’re stalking, as they tack and jibe on the water below. We clatter toward the first pair of boats at more than a hundred knots.

It’s still ten weeks before the qualifying races kick off on October 1, and the actual America’s Cup, a silver goblet weighing almost 30 pounds, won’t be awarded until February, following a climactic kill-or-be-killed duel between a battle-dented challenger and the Cup’s defender, Team New Zealand. But the 19 new Cup-class yachts that will fight for the trophy are the most sophisticated racers that money, technology, and human ingenuity can produce, and with a half-billion dollars invested, they’re treated like top-secret weapons systems. Even taking pictures is mostly forbidden, so catching them in action calls for a slightly unorthodox approach—in this case a chartered Bell 206B JetRanger III.

White drops in near the stiletto-thin, charcoal-black hulls of Oracle BMW Racing’s two yachts and settles into a hover. The boats spin and circle each other, the sun glinting off their sails as they engage in a pre-start dance. Faces aboard the Oracle RIBs—the high-powered rigid inflatable boats that constantly swarm around the racing craft—turn skyward to identify the intruder. But the sailors are too busy with their practice race to take much notice, and hit the starting line just as the gun fires. After watching them knife upwind for a few minutes, it’s time we moved on.

“Let’s go find OneWorld,” I say, and White smoothly spins the chopper in the direction of two indigo-blue hulls in the distance.

Within minutes White has us hovering just above the Hauraki wavelets as the 80-foot yachts of the OneWorld Challenge syndicate accelerate toward us. An RIB breaks from the pack and roars our way, a crewman waving his arms wildly to shoo us off. We rise into the sky, and the boats continue up the racecourse. Finally, the sailors can tolerate our presence no longer. The two boats break off their practice, headsails shivering down to the deck.

We drift back toward Oracle, but a call comes in on the VHF. The team has contacted White’s base at North Shore Helicopters to order us to back off. When we eventually touch down again at the airfield, I switch on my cell phone, and the display shows four calls from OneWorld. Word of our airborne stunt has already traveled across the Pacific to the Seattle home of Bob Ratliffe, OneWorld’s executive director, and he’s pissed. He unloads into my voice mail: “You didn’t have permission to be up there taking pictures of our boats!”

IT TAKES AN IMPRESSIVE COMBINATION of hubris and paranoia to try to claim control over a nation’s airspace. But the America’s Cup is hardly your average weekend regatta. It’s a grueling, multiyear campaign, and a staggering display of money, technology, and ego. Sixty-two-year-old William Koch, who dropped some $68 million on the campaign that won the Cup in 1992, calls it “the most ruthless sporting contest I have ever seen.” Naturally, the powerful people behind the syndicates are used to getting their way and will happily resort to all manner of skullduggery, legal shenanigans, crew poaching, and outright intimidation to win.

Software mogul Larry Ellison, the founder and CEO of Oracle, the computer database giant, heads the current crop of billionaires and near-billionaires—known simply as the B’s—who are making this America’s Cup the costliest and most cutthroat in the race’s 152-year history. Ellison, 57, has funded his San Francisco├Ébased Cup attempt with roughly $80 million, a fraction of his estimated $15.2 billion personal fortune. With BMW kicking in an extra $20 million, Oracle BMW Racing is a daunting force, boasting more staff (142), more technology (the boss monitored his yachts’ performance in real time from his Northern California desktop), and more swagger (Ellison has flatly declared that Oracle BMW is “the team to beat”) than any of its rivals.

Not that the three other $50-million-plus syndicates are running scared. The roster includes Seattle-based OneWorld, backed by telecommunications pioneer Craig McCaw, 53, and Microsoft cofounder Paul Allen, 49; Switzerland’s Alinghi, the brainchild of 37-year-old pharmaceutical heir Ernesto Bertarelli; and the talented team that lost to New Zealand last time out, Italy’s Prada, the plaything of fashion-house honcho Patrizio Bertelli, 56. Five lesser syndicates are in the hunt, too. One closely watched underdog is Team Dennis Conner, backed by the New York Yacht Club and led by San Diego’s Conner, 60, who has won the America’s Cup four times and lost it twice, making him the most experienced Cup sailor in history.

Over the past three years, all this money and megalomania has been funneled into a quarter-mile stretch of Auckland waterfront called Syndicate Row. Here, on Viaduct Harbor, huge aircraft-style hangars loom within spitting distance of one another, like a big-box retail development gone mad. This miniature city of sail lofts, cafeterias, offices, and rigging shops has transformed what was once a series of crumbling cement fishing piers into a Formula One—style pit row.

In the center of it all, the pink-and-silver-hued Alinghi compound, created by merging two vintage-2000 syndicate bases together, rises above its neighbors, Team New Zealand and OneWorld. Farther down the pier, Oracle BMW Racing has moored a multilevel floating barge that serves as an office area and mess hall. Suitable creature comforts are close at hand: Aside from the $300 million worth of luxury condos that have sprung up in the neighborhood, Ellison’s palatial 248-foot yacht, Katana, is on semipermanent station directly across from the Oracle base.

The teams are packed tight, and they aren’t very neighborly. America’s Cup syndicates have been jealously guarding their yacht designs since the turn of the century, when workers at the Herreshoff boatyard in Bristol, Rhode Island, used hot rivets to pelt a journalist trying to steal a look at Reliance, the defending yacht. Today, a culture of extreme secrecy permeates Viaduct Harbor. Security fences and video surveillance cameras give Halsey Street, which runs the length of Syndicate Row, a military feel. Oracle employs three full-time guards to keep spies away, and the rent-a-cops were put to the test at least once earlier this year, when a local reality-TV show sent a team of kayakers paddling under the syndicate’s docks.

Snooping is so much a part of America’s Cup culture that the rules of engagement are laid out in The Protocol, a 33-page document that was hammered out in the months following the 2000 America’s Cup by Prada and the Royal New Zealand Yacht Squadron to give the competition some semblance of order. Section 13, called “Reconnaissance,” allows any team to take pictures of another team’s yacht on the water from a distance of at least 660 feet, or at a public unveiling event, but its rules are mostly about what you can’t do. It forbids an array of surveillance techniques, including divers, submarines, satellites, computer hacking, dumpster diving, lasers, radar, and helicopters.

If this seems over the top, consider the 1992 Cup competition in San Diego. That year, scuba bubbles appeared under the keel of Dennis Conner’s Stars & Stripes as it was being lowered into the water. A crew member tried to spear the mystery swimmer with a long stick used for clearing kelp from the keel, and then dove in after him. The diver escaped. But a hollowed-out flashlight containing what looked like a measuring device was later found under the boat, leaving Conner speculating about which rival might have hired a spy. In 1995 in San Diego, feuds erupted on a regular basis as RIB drivers took to ramming one another on the ocean to keep rival cameras away from their boats.

THIS YEAR’S COMPETITION is already rife with sideshows. In July, Prada initiated proceedings to haul Oracle BMW into a New Zealand court, charging that the position of Oracle’s barge—and its then-tinted windows—allowed covert surveillance into Prada’s boatyard. In another confrontation, last December Team New Zealand hustled over to the Alinghi compound and demanded to be given the film taken by a visiting family member of an Alinghi crewman. Why? The snapshots were allegedly taken from an angle that showed a Team New Zealand boat passing in the background. By last summer, the America’s Cup Arbitration Panel—created by the challengers and the defender to resolve their spats out of court—had received no fewer than 18 formal complaints. It refused to issue any rulings until August, when the notoriously litigious syndicates finally promised not to sue in a real court if they didn’t like the panel’s verdict.

Making the race even more byzantine, the mountain of deeds, protocols, class rules, and legal interpretations that govern the America’s Cup has swollen to more than 150 single-spaced pages, and is often so nebulous that the syndicates employ full-time “rules advisers” to translate their meaning. In this year’s most serious flap, Team New Zealand hounded OneWorld for months, accusing it of illegally possessing design data brought by a Kiwi designer who had switched teams. The fracas was settled in August when OneWorld was assessed a one-point penalty, which will be deducted from its score after the two initial round-robins of the challenger series end on November 1. OneWorld, which admitted the breach but argued that it was insignificant, was probably just thankful not to be thrown out of the race.

While the lawyers and advisers battle it out behind closed doors, the sailors—most of whom know each other from the pro sailing circuit—try to keep things light. An unspoken rule prevents them from asking anything even remotely probing when they bump into each other at the popular Portside Brasserie on Syndicate Row. But that doesn’t stop them from having a little fun when they notice something interesting going on next door.

“We were putting a mast in a boat and got a call from Team New Zealand asking, ‘Are you sure you’re doing that right?’ ” says John Barnitt, 41, a grinder for the Alinghi team. The tease was payback for an incident earlier in the year, when the Kiwis, thought to be testing a radical new bow rudder design, waited until after sundown every night to lift their boats from the water. “Of course, we stuck around and gave them shit,” explains Barnitt.

As it is, almost nothing can happen in Viaduct Harbor without the other teams noticing. From a public pier located just 100 feet across a narrow channel from the compounds, I was able to watch every morning as the boats were trundled out of the sheds and launched for the day’s racing or training. Still, the teams take elaborate precautions to protect whatever secrets they can. Every evening, most boats are draped with skirts to hide their keels and hull shapes as they are craned from the water back into the boat sheds, where any modifications can take place in secret.

Trying to get a glimpse behind the veil can become an addicting hobby. One night I arrange to meet Cheryl Cliffe, a 56-year-old senior lecturer at the University of Auckland, at the Loaded Hog, a waterside pub decorated with quarter-scale models of past America’s Cup boats. Cliffe says she was never really into sailing until the America’s Cup came to town, but she’s become one of the most prolific agents for a Web forum called the Spy Network, accessible via www.2003ac.com. There, she shares descriptions of bow shapes and whatever hull characteristics she can glimpse when a skirt slips.

“It’s only a boat race,” she tells me, slightly embarrassed by her obsession. “But it’s also a lot of fun.”

THE AMERICA’S CUP has always attracted more than its share of obsessed tycoons. It began in 1851, when the New York Yacht Club schooner America crushed a fleet of Britain’s fastest yachts in a race around the Isle of Wight. America‘s syndicate of wealthy owners won an ornate silver ewer that they renamed the America’s Cup. Then they dared all comers to try and win it.

Over the decades, many a rich guy has stepped up to the challenge, often keeping sailing fans well entertained. Throughout a 31-year period starting in 1899, tea magnate Sir Thomas Lipton attempted in vain to win the prize back for England. (“I canna win, I canna win,” he moaned at the age of 80, following his fifth and final defeat.) Frenchman Baron Marcel Bich, the Bic pen magnate, blew $6 million on his first challenge, in 1970, and millions more on three additional bids, and never even made the finals. In 1977, Ted Turner trash-talked his way to victory aboard Courageous—much to the dismay of the overstarched New York Yacht Club. With drunken exuberance, he ended up under the table at his celebratory press conference.

Throughout all these shenanigans, the Cup remained in American hands for an incredible 132 years, the longest winning streak in sports. In 1983, Dennis Conner’s Liberty finally lost to the Australians, who had developed a top-secret winged keel for their yacht Australia II. Conner won it back in 1987 aboard Stars & Stripes, only to lose to Team New Zealand’s Black Magic eight years later. Today the prize stands behind armored glass at the Royal New Zealand Yacht Squadron, just a mile or so from Syndicate Row, protected by alarms and a hardened steel box that drops over it every night. The Mission: Impossible stuff isn’t just for show: In 1996 a Maori activist took a sledgehammer to the Cup, leaving it a dented, twisted mess that only Garrard of London, its original manufacturer, could repair.

Since stealing the Cup is out of the question, the only way to get it is to win it, match-racing sailboats in a four-month series of one-on-one duels that will ultimately pit a single challenger against Team New Zealand. The challenger trials, known since 1983 as the Louis Vuitton Cup, started October 1 and will subject nine teams to a pair of round-robins. Every race during this phase is worth one point. By November 1, a single challenger will be eliminated and the remaining eight will drop into a complex seeded draw, starting November 12. These seedings will be critical, because the top four boats in this elimination round are allowed to lose twice before exiting the competition, while the bottom four can lose only once. The double-chance format means the surviving challenger could arrive at the February 15 America’s Cup final having thrashed it out through as many as 53 races.

“It’s brutal,” says Kevin Hall, a 33-year-old navigator with OneWorld. “You have to be up on the day, and keep it up for months.”

While the drama hasn’t changed, just about everything else has. Until World War II, the America’s Cup was sailed in enormous schooners and sloops, often more than 100 feet long, with dozens of crew and clouds of sail. In the modern era, design formulas that allow just enough latitude for innovation while producing recognizably similar boats create closer, more intense races.

Today’s America’s Cup yachts employ the very latest materials and designs. The 80-foot hulls are literally baked from carbon fiber; about 20 tons of their total 25-ton weight is packed into a torpedo-shaped lead keel. Almost everything on board, from spinnaker poles to steering wheels, is custom-made. The boats sail against each other on an 18-and-a-half-mile course, traveling at speeds up to about 18 knots. An advantage of just a 20th of a knot can translate into a crucial few boat lengths on the first three-and-a-quarter-mile leg of the course, and can represent the margin between winning and losing.

Even the smallest speed advantage is so crucial that designers and engineers strip their craft of every excess pound. Each night the boats are dehumidified in their sheds to dry out water absorbed by the hulls. Any fitting that can be lightened without sacrificing structural integrity is drilled full of holes. Sometimes the engineers go just a fraction too far. Rigs fall, keels snap off, and sails shred. It’s hardly an America’s Cup unless at least one boat sinks or folds like a jackknife.

“Safety margins are nonexistent,” says Rob Humphreys, a 52-year-old designer with GBR Challenge, Great Britain’s syndicate. “We cut it as close as possible.”

It can be tempting to conclude that technology and boat speed are all it takes to win the America’s Cup. Oracle BMW’s boats, for example, have sensors on almost every moving part, and over two years of testing the team has amassed some 700 hours’ worth of performance data. As a result, the onboard computer knows the fastest trim settings for almost every wind speed and angle.

But an afternoon out on the Hauraki Gulf with the refreshingly press-friendly Swedish Victory Challenge team reminded me that technology, while powerful, is not the whole story. I watched as bright digital displays mounted to the mast told helmsman Jesper Bank, 44, the target wind angle and target boat speed that would get him to the next mark fastest.

In theory, Bank didn’t even need to look at the sails; he could simply steer the boat up or down until he hit the target numbers. I mentioned this to Skip Lissiman, Victory Challenge’s 45-year-old Australian coach, and he invited me to take the helm. Despite my slavish attention to the readouts, the boat speed dropped by up to half a knot. Bank and Lissiman chuckled. Don’t be fooled, their grins said. A fast boat is vital, but it still takes an elite skipper and crew to realize its potential.

CLOSE YOUR EYES and try to imagine Lance Armstrong ditching U.S. Postal to take up with a European cycling team. You’ll feel just a trace of the outrage that swept New Zealand in May 2000. That’s when Russell Coutts, a 40-year-old Kiwi and perhaps the best pure match racer on the planet, and 43-year-old countryman Brad Butterworth, his longtime tactician, jumped ship from Team New Zealand to Ernesto Bertarelli’s Alinghi syndicate.

Coutts and Butterworth, who took some of New Zealand’s best sail trimmers with them, had been expected to lead their homeland’s 2003 defense. To this day they have refused to publicly discuss the internal organizational disagreements that drove them offshore, but a pair of rumored $5 million Alinghi contracts likely helped close the deal.

New Zealand media equated the defections with treason (“TRAITORS!” blared a headline in the Sunday News, a weekly tabloid.) To appreciate the fuss, it’s important to understand New Zealand’s total obsession with sailing. When the Commonwealth country of four million first won the America’s Cup, in 1995, the feat was compared to Hillary’s first ascent of Mount Everest. Prime Minister Jim Bolger declared the day an unofficial holiday.

Now, two years after the defection, the buzz in Auckland ranges from the still-seething—”I’m surprised they let him back in the country,” growls one patron at the Loaded Hog—to a more benign view of Coutts as a money-struck prodigal son.

For his part, Coutts says he is enjoying his new life as a Swiss national—America’s Cup rules require team members to establish residency—and blithely explains away his new allegiance as a boon to competition. “Look at the talent that’s spread throughout these teams,” he says. “This is the best America’s Cup yet.”

But you have to wonder about the conflicting emotions he and Butterworth will go through if Alinghi wins the Louis Vuitton Cup and lines up in February against Team New Zealand.

Whether that dramatic moment arrives will depend a lot on Larry Ellison and the sailors, boatbuilders, and support crew of Oracle BMW Racing. Ellison jumped into the 31st America’s Cup on the kind of whim only a multibillionaire could afford. In May 2000, while celebrating victory at Antigua Race Week’s awards dinner, he was chatting with Tony Rae, one of several Team New Zealand sailors who regularly sailed aboard Ellison’s 80-foot racing yacht Sayonara. Rae told Ellison about the plundering of Team New Zealand’s talent. This gave Ellison bright ideas about what his money could buy.

“You mean I could sail with you in the America’s Cup?” Ellison asked.

“Yes,” Rae answered—although he ultimately remained loyal to New Zealand.

“Well, let’s do it,” Ellison responded, committing himself to a multimillion-dollar investment as if he were ordering a cup of decaf.

With Ellison, anything is possible. He’s famous in Silicon Valley for being supremely self-confident, always hungry to win, and willing to spend whatever it takes. He’s a skilled amateur skipper who has been steering Sayonara to victory in the world’s top regattas since 1995. To kick off his America’s Cup campaign, he snapped up the 2000-vintage boats used by fellow San Franciscan Paul Cayard’s AmericaOne syndicate, and set Annapolis-based Bruce Farr—the best yacht designer never to have won the Cup—loose on plans for two new yachts.

Ellison then leveraged his resources to create a computerized design program that allowed Farr to scroll through hundreds of virtual Cup-class boats, probing every possibility for marginal increments of speed. Farr ended up running through as many as 500 hulls a day. (A standard design program might analyze a handful.) Using a so-called velocity-prediction program, which takes the myriad design parameters of a boat—like length, displacement, sail area, and beam—and speculates how it will perform over a range of wind angles and wind speeds, Farr staged millions of “races” between the most promising hulls. Test results were sent around the world almost instantly to everyone in the design team, allowing the group to sort through data and move ahead while other syndicates were still manually collating information and banging out e-mails.

At the same time, Oracle BMW Racing created its own wind tunnel in Ventura, California, to test hundreds of sail shapes. And down on the Hauraki Gulf, a meteorology team led by American Bob Rice, the best-known sailing forecaster in the business, was gathering round-the-clock wind speed and direction data using a fleet of six boats and a weather buoy rented exclusively to Oracle. Rice, 71, was delighted by the resources that Oracle threw his way.

“It was almost as simple as ├öWhat do you need?’ ” he says.

Out of this sophisticated and seamless integration of design, sail, and wind data emerged a striking pair of race boats that are narrow as missiles, with slightly upturned canoe-style bows. And given Ellison’s lust for competition, no one raised an eyebrow when he made it clear that at times he plans to drive the boat himself. That part of the plan has rivals detecting an ego trip, but Ellison could pull it off. Bill Koch spent some time behind the wheel in his successful 1992 campaign.

“If [Ellison’s] boat is fast enough,” Dennis Conner says, “and someone is standing alongside him saying, ‘Steer up a little’ or ‘Steer down a little,’ and he has a two-minute lead, he’ll be just like Koch. Smile at the TV cameras!”

Theatrics aside, Ellison is smart enough to stay out of the way and leave the heavy pre-start driving to Peter Holmberg, 41, the last professional helmsman left standing at Oracle BMW racing. That way he’ll avoid the likes of Peter Gilmour, 42, OneWorld’s lead helmsman and a notoriously aggressive match racer who would enjoy nothing more than carving up a guy like Ellison. Gilmour is a pug-faced Australian and a canny, hard-nosed sailor who in his younger America’s Cup days was known as “Crash.”

“Gilly is always willing to put the knife in,” says Ian Walker, GBR Challenge’s skipper. Gilmour himself only partially disagrees.

“Typically, as you get older you get more conservative in your boat handling. It’s the young guys that don’t give a fuck,” he says. “But as the great match racer Harold Cudmore once told me, ‘I don’t have any moves myself. I just wait for the other guy to make a move and pounce.'”

DAY AFTER DAY in the coming months, the nine challengers will submit themselves to the grueling test of the Louis Vuitton Cup. In an endless series of cliffhangers, every boat and crew will be probed for weakness. Did Oracle BMW Racing spend Ellison’s millions wisely, or did GBR Challenge, Team Dennis Conner, or Victory Challenge somehow find more boat speed at half the cost? Will Prada come back stronger after its meltdown in the 2000 America’s Cup final, or is the team still singed? Will Coutts and Butterworth have enough pure talent to lead a first-time Swiss syndicate to victory?

Regardless of the answers, every challenger is united in a single goal: to beat Team New Zealand. “They have had the Cup for too long,” read a memo posted at Team Dennis Conner’s California training base. “It costs the taxpayer too much to stage it, all the good guys left the home team…all the locals do is complain about having it. We will be doing them a favor if we take it with us when we leave.”

As the challengers jockey for a place, Team New Zealand will be lying in wait, carefully observing, refining its boats based on what they see. Not that New Zealand needs much of an edge. The little island nation produces elite sailors like East Africa produces long-distance runners, and has transformed itself from a first-time challenger in 1987 to an America’s Cup powerhouse. Team New Zealand won a staggering 41 of 43 races to take the challenger series in 1995, and blanked Dennis Conner 5├É0 in the America’s Cup final to bring the trophy to Auckland. In 2000, Coutts and company also dismantled Prada 5├É0, leading at every mark of every race.

Despite the talent drain and Team New Zealand’s relative poverty—its $40 million budget is less than Larry Ellison dropped on Katana—most of the sailors along Syndicate Row expect a real dogfight in the final. Team New Zealand’s supporters say it has been reborn, led by Dean Barker, Coutts’s heir apparent, and the young guns who stayed loyal. Barker, 29, is a natural and gifted sailor who seems at ease with his new superstar role as he tools around Auckland in a Lexus coupe—a loaner from team sponsor Toyota. He was Coutts’s sparring partner for the 2000 Cup, and he beat the master in roughly half their practice races. Opponents describe Barker as being a magical sailor. “Sometimes he is simply unbeatable,” says Victory Challenge’s Jesper Bank. “When he is at his best, he’ll always come out of tight situations on top.”

If Barker has a weakness, though, it is his inconsistency. The job of keeping him focused falls to Team New Zealand syndicate chief Tom Schnackenberg. A former nuclear physicist, Schnackenberg, 57, has been involved in the America’s Cup since 1977 and is now in his eighth campaign. Dennis Conner calls him “the best brain in sailing.” Laid-back and cerebral, he mixes sailors, designers, and inspiration together like an alchemist, and always seems to come up with superior boat speed.

Sitting in a meeting room at Team New Zealand’s base, Schnackenberg puts his feet up on the table and talks modestly about his chances. But you can tell he is relishing the idea of beating the odds once again, of working his magic to outsail the most determined big-money assault the Cup has ever seen. He just doesn’t think it will be as easy.

“In 1995 no one saw us coming. No one rated us,” he says. “In 2000, people took aim at us but missed completely by aiming at where we were in ’95. This time around I can’t fault what anyone has done at all.”

No one knows what Schnackenberg and Team New Zealand have come up with, and no one will see it until February, when the yachts are unveiled just prior to the Cup finals. Does Schnackenberg have some critical innovation up his sleeve?

“If you can make just a bit of effort and create a reaction, then you make a gain,” he says with a grin. “But when it comes to boat speed, the truth will always out.”

GIVEN THE HEAD GAMES, paranoia, and legal mud-wrestling that go on in the America’s Cup, it might be easy to see the race as a sporting sideshow for obscenely rich, spoiled men. But to understand why it is, in fact, one of the most compelling dramas sailing can offer, it is only necessary to step into an America’s Cup yacht and go racing.

That’s exactly what I did last July—with Team Dennis Conner, on the cobalt waters off Long Beach, California. In the tang of a gathering sea breeze, listening to the click of pawls as winches spun and the quiet talk of trim and tactics, all the Machiavellian intrigue faded like so much sea smoke. I stood at the back of USA-66, one of the syndicate’s two new America’s Cup boats, trying to keep all my body parts intact as loaded blocks and lines whipped past my head. The five-minute gun had just cracked across the water, counting down to the start, and mayhem was headed our way in the form of USA-54, with Ken Read, multiple world champion and the team’s principal helmsman, at the wheel.

The few minutes before a match race amount to a fast-moving duel in which the two boats attack, spin, and feint, looking to force a penalty or establish any positional advantage to carry into the race. The two yachts usually charge directly at each other in a game of chicken, and Read and Tony Rey, who was driving my boat, followed the script at a closing speed of 20 knots. Just when I thought it was impossible for them to avoid a carbon-splintering collision, the two drivers deftly spun their helms and both boats shot head-to-wind, white rooster tails exploding out from under their scooped sterns. The boats slowed and came within a few feet of each other, sails cracking like machine-gun fire.

A 25-ton, 80-foot yacht moving at a crawl is like an uncoordinated boxer, and the sailors aboard the two Team Dennis Conner boats worked with total concentration. Rey and his crew skillfully brought the boat to a near-standstill, pointed into the wind and on the verge of stalling out. Read’s boat was still creeping ahead, which was just the opening Rey and tactician Peter Isler were looking for.

With smooth proficiency, the trimmers backed the jib, and the mainsail was eased, swinging the bow around. Rey added a touch of wheel and USA-66 ducked behind USA-54, clearing her stern by inches. It was done quickly and quietly. The only real noise was the sheets screeching through the blocks and the deafening creak when one running backstay was let off and the other was ground on hard.

“Beautiful,” Rey concluded. For four minutes, Read gave chase. Finally, the two boats powered back toward the start line. USA-66 crossed at the gun with a three-second advantage. The race was on.

Sailing can be a complex and confusing game, with enormous fleets and mind-numbing handicap systems. Yet there is a raw simplicity to match-racing sailboats that is irresistible. Every time the boats crossed tacks that morning, you could see who was ahead. Every time a spinnaker ripped or a line snagged, even if only for a few seconds, you could measure the cost in distance lost. It was both agonizing and exhilarating—and the America’s Cup, with the sophistication of its technology, the years of training, and the pressure of the racing itself, takes this purity of competition to an extreme found only at the highest levels of sport. “You’ve either won the race or you’ve lost it,” says John Cutler, a tactician with Oracle BMW. “It’s a blunt measure of you, your team, and your equipment.”

By this measure, nothing matters except who crosses the finish line first. That’s why they come, and why they spend millions. And it’s also why the winners can lay claim to being the best sailors in the world.

Playing the Field

Over the next four months, nine syndicates will slog it out in the waters off Auckland for the right to challenge Team New Zealand, the current defender of the America’s Cup. Here’s how the competition shakes out.

DEFENDER:

Team New Zealand Country: New Zealand Yacht Club: Royal New Zealand Yacht Squadron Helmsman: Dean Barker Budget: $40 million*

CHALLENGING SYNDICATES:

Alinghi Team Country: Switzerland Yacht Club: Soci├®e;t├®e; Nautique de Geneve Helmsmen: Russell Coutts, Jochen Schuemann Budget: $55 million

GBR CHALLENGE Country: Great Britain Yacht Club: Royal Ocean Racing Club Helmsmen: Andrew Beadsworth, Andrew Green, Ian Walker Budget: $31 million

Le D├®e;fi Areva Country: France Yacht Club: Union Nationale pour la Course au Large Helmsmen: Luc Pillot, Philippe Presti Budget: $25 million

Mascalzone Latino Country: Italy Yacht Club: Reale Yacht Club Canottieri Savoia Helmsman: Paolo Cian Budget: $25 million

Prada Challenge Country: Italy Yacht Club: Punta Ala Helmsmen: Francesco de Angelis, Gavin Brady, Rod Davis Budget: $50 million

OneWorld Challenge Country: USA Yacht Club: Seattle Yacht Club Helmsmen: Peter Gilmour, James Spithill Budget: $75 million

Oracle BMW Racing Country: USA Yacht Club: Golden Gate Yacht Club Helmsman: Peter Holmberg Budget: $100 million

Team Dennis Conner Country: USA Yacht Club: New York Yacht Club Helmsman: Ken Read Budget: $30 to $40 million

Victory Challenge Country: Sweden Yacht Club: Gamla Stans Yacht S├żllskap Helmsmen: Magnus Holmberg, Jesper Bank Budget: $25 to $30 million

*All budget figures are estimated