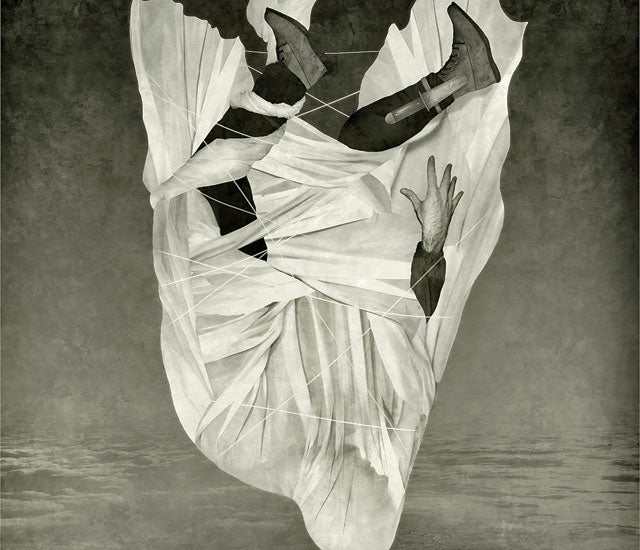

Drowned

How do you save someone who's already dead? Rafa Ortiz, Rush Sturges, and Gerd Serrasolses found out.

The Rio Tulijá is a remote white-water river that snakes its way through the rainforest of southern Mexico. Often called Agua Azul because of its swimming-pool-blue color, it features a stunning stretch of five waterfalls ranging from 40 to 70 feet tall. This past March, a team of four world-class kayakers—Rafa Ortiz, 26, Rush Sturges, 28, Evan “E.G.” Garcia, 27, and Gerd Serrasolses, 24—attempted to descend the falls as part of an expedition they were filming for a documentary. The previous day, they had become the first paddlers to drop all five waterfalls on the nearby Río Santo Domingo, arguably the steepest navigable section of whitewater on earth. The Agua Azul mission was to be their final day of filming:

RUSH STURGES: We were coming off the biggest descent of our lives and were tired and sore. I had two black eyes and a broken nose. We were really pushing ourselves to get this helicopter footage on the Agua Azul.

E.G.: We had driven six or seven hours in Rafa’s van, slept for like five hours, then woken up at about 6 a.m. The plan was to meet the heli in these flat pools about two-thirds of the way down to the big waterfall set.

RAFA ORTIZ: At the pools, I paddled upstream, away from the guys, to get in my zone, and Gerd kept practicing his hand rolls.

GERD SERRASOLSES: As soon as we saw the chopper, we all got fired up.

E.G.: We had scouted the hell out of the falls when we ran them a week earlier, so I knew exactly where I was going.

GERD: We had to pretty much go one after the other. I watched Evan drop over the lip, then Rush. I wasn’t too nervous. I had done it before and knew what I had to do. I went over and threw my paddle.

E.G.: I got out of my boat and was standing on a ledge about 25 feet from the base of the falls. I watched Rush come off. Gerd came next on a similar line, but he corked out and missed a few hand rolls.

GERD: I tried to roll up, but I wasn’t feeling any grab.

RUSH: E.G. and I were right there with throw bags, but I didn’t think it was that bad.

GERD: I tried to roll a few more times, then got pushed up against some rocks. I grabbed them, but my hands slipped and the water pushed me back down somewhere else.

RUSH: Gerd’s boat was full of water and spinning like crazy in this vortex of an eddy. We’re not seeing him come up. Fifteen seconds go by. Twenty. Thirty. I was like, Dude, we gotta do something.

GERD: I kept fighting to get to the surface, but I couldn’t get there. I remember opening my eyes and saying, Fuck, I’m running out of air.

RUSH: He’s under for about a minute and a half, and we’re panicking. I clipped E.G.’s rope into the back of my life jacket and went over to the spot where Gerd disappeared. I stuck my leg in the water and could feel it sucking down super hard, like a siphon. I didn’t want to go

in there.

E.G.: I looked downstream and suddenly saw Gerd’s yellow vest.

RUSH: He was facedown. It was the absolute worst-case scenario.

E.G.: I jumped into Rush’s kayak. No helmet, no skirt. I paddled like a bat out of hell in this heinously flat pool.

RUSH: Gerd was probably 100 yards downstream from us, and the next waterfall was coming up soon.

E.G.: Rafa actually ran the first waterfall while this whole thing was going on.

RAFA: At the bottom I looked around, and there’s no one there. Then I see Gerd floating facedown and E.G. and Rush chasing him.

E.G.: When I pulled him up he was super heavy—like some weird Jell-O object. I was screaming and slapping his back, then started in on CPR. Rush and Rafa got there about 20 seconds later.

RAFA: Gerd’s eyes were open a little but not showing life, and he was a mixture of white, purple, and black—the color you see in zombie movies.

RUSH: We were taking turns at CPR and slapping him in the face. It was a primal feeling, just the strongest desire to save a friend.

E.G.: I was yelling at him, “Come on, Gerd! Fight!” He was vomiting up some real nasty mucus and blood. Then we got the idea to pull off his life jacket, and we loosened the neck gasket on his drytop.

RAFA: For four minutes, we were doing CPR on a dead body. I don’t remember having much hope. But then he took a breath.

RUSH: His eyes literally lit up.

RAFA: That’s when I jumped up and started looking for the heli.

RUSH: The chopper hovered over the middle of the river. We carried Gerd to it, and Rafa jumped in with him. He was breathing a bit but still convulsing and coughing up water.

E.G.: After the chopper flew away, there was this weird quiet.

GERD: The next thing I remember is trying to wake up. I was hearing all these loud noises—the chopper, screaming—but I couldn’t react, and I couldn’t see anything. Inside, I was screaming to try and regain power. And then I woke up in the hospital in Palenque. —Mark Anders

Stuck

On a fall day in a Utah canyon, 25-year-old Robbie Tesar WAS nearly swallowed by quicksand.

It was late fall 2011, and I was three weeks into a course with the National Outdoor Leadership School in southeastern Utah, hiking with three other students along the Dirty Devil River. Around midday, we came to a point where the canyon wall met the river. A sandbank extended into the water, and I walked out on it with another guy. About 20 feet from shore, I suddenly sank knee deep. The other guy did, too, but only one foot. After 15 minutes of struggling, it was clear we were going to need some leverage. The two students on shore helped us rig a pulley so we could yank ourselves out. After about an hour, the other guy was able to slip out of his boot. He and one of the other two students went for help while the last one stayed with me.

It was about 65 degrees out when I first got stuck, and I was wearing cotton work pants and a long-sleeved wool shirt. When the sun went behind the canyon wall at around 3 p.m., it got cold, and I was wet. I put on a couple of jackets. The runners came back after not finding anyone, and we agreed to activate a personal locator beacon. They passed me warm food and hot water over the pulley. We built a raft using a sleeping pad and sticks so I could rest my upper body without sinking deeper. From my waist down I went mostly numb, though I kept my leg muscles moving.

A helicopter arrived at about 8 p.m. The plan was for me to build a harness with some webbing and tie it to one of the skids, then the chopper would take off while I held on to the skid. But when it started pulling, I didn't move. On the fourth try, I felt my back go pop. I heard the pilot say over the radio, “If I try this again, I'm going to rip the kid in half.”

The helicopter left to get more help. When the rescuers got back, they passed me a backboard and a shovel, but I couldn't get any leverage to dig. Then ten guys got into rafts on either side of me. I held on to the sides while others dug. I finally broke free around 2 A.m. I was so elated that I tried to step into a raft and face-planted.

At the hospital, after they warmed me up, they wanted to give me a shower. I couldn't stand, so they said I could get help from either a guy named Jed or these two beautiful nurses. I hadn't bathed in 25 days. “I'll take Jed,” I said. “I'm in no state to be showering with women.” —Joe Spring

Overboard

When 50-year-old South African surfer Brett Archibald fell from a chartered 72-foot motor-boat this past spring, during an overnight crossing from Sumatra to the Mentawai Islands, he was some 40 miles from the nearest shore.

April 17—1:30 A.M.

I woke up feeling sick and went to the head and immediately started exploding out both ends—it was food poisoning. I went on deck to throw up and saw one of my mates, who was also sick. I went and told the captain, then went back outside. That’s the last thing I remember until I came to in the ocean and saw the boat about 200 feet from me, sailing away. I must have fallen over the railing. I screamed, but I knew it was futile.

April 17—3 A.M.

I decided I had two choices: live or die. I chose to live. I immediately started focusing on getting my heart rate down, using breathing and meditation. Thankfully, the water was about 82 degrees.

April 17—2:30 P.M.

I knew the guys would look for me. And that afternoon, as a storm was lashing, the boat came along. It was within 350 feet, but because of the rain my mates couldn’t see me. I screamed and swam toward them, but the current dragged me sideways. The boat stopped, and I thought they saw me, but a minute later they sailed away. That was a meltdown moment. I thought, That’s it, I’m done.

April 17—Sunset

Something hit me on my left side. Fish had been nibbling at the back of my leg, so I was bleeding. Then it hit again, harder. I wanted to see what it was, so I swam under-water and looked right at a blacktip reef shark about my size. I thought, At least it will be quick. Then I realized, Wait, it’s a reef shark. If he attacks me, I’ll shove my arm down its mouth and have it drag me into a reef. Then it was gone.

April 18—7 A.M.

A fishing boat sailed straight at me. But it must have reached some coordinate, because it turned sharply and sailed away. Right then I thought, I can’t do this anymore. Before the trip, my wife had read me a story about drowning being a beautiful way to die. I tried to suck down some water, but it didn’t work. So I went about six feet under and breathed. It was actually quite easy. The water came in through my mouth and out my nose. Then my brain went, What the hell are you doing? and I came up like I had an engine. While I was sputtering at the surface, I saw a cross coming at me—a mast. I put my head down and swam while counting to 1,000. When I looked up, I saw four spotters on the roof of the boat. I screamed. They couldn’t see me, but they could hear me. They eventually located me with binoculars. I’d never been so happy to see a boat in my entire life—even if it was full of Aussies! —Ben Marcus

Falling

One bad decision sends northern California skydiver Craig Stapletoon toward a crushing impact

My skydive teammate Katie and I had planned a formation for a jump last March where we would float a giant U.S. flag between our two flying parachutes. I had done about 7,000 jumps and competed in six world meets and probably 14 nationals. I’m also the safety adviser for my local drop zone here in Lodi. Katie looked at me as we were getting on the plane and said, “I don’t have a knife. Is that a problem?” I took mine from my chest pouch and handed it to her. In 25 years, I had never needed one. Plus, I had a backup attached to my leg.

We started our trick at 6,000 feet. Katie placed her parachute just below me, so I could put my feet in the lines. I passed one end of the lanyard we’d use to hold the flag down to her, and she clipped in. At that point, we were supposed to move away from each other horizontally, but we ended up moving apart vertically, and I got jolted so hard when the lanyard straightened out that I was flung forward and upside down. My right ankle got caught in one of my lines, and my chute inverted, then circled around itself and knotted. The lanyard was around my neck.

At about 4,800 feet, Katie released her end of the lanyard, setting me free, then I pulled the handle to release my main parachute, but only the left side came off. I was spinning so wildly, I couldn’t grab the knife from my leg. At 1,800 feet, I fired my reserve parachute while tangled up, but the main parachute just started eating it as soon as it opened.

I was falling at 30 to 35 miles per hour. I looked down and saw vineyards. There were grape plants every four to five feet. Inside each one was an iron spike about six feet tall, and they were all strung together with fencing wire. I visualized the horrible things that were about to happen to me. I said goodbye to my wife and kids and apologized to them. I thought, Just relax as much as you can, roll with the impact, and exhale.

Next thing I know I was lying on the ground. I’d landed between all the wires, in dirt that had just been plowed, so it was like really fine sand. Katie called 911, and the emergency crew came pretty rapidly. They cut my jumpsuit off and looked at me. I didn’t have internal bleeding, just a separated left shoulder, and my left side was really sore. The best news I heard was the fire chief canceling the helicopter.

My wife was signing into the security desk at the hospital when I walked out. All she wanted to do was give me a hug, but I was like, “No hug! I can’t take it!” —J.��.

Shot

Two months into a planned source-to-sea expedition down the Amazon River, 24-year-old adventurer Davey du Plessis was in his kayak when the first shotgun blast hit his back.

I was having my best day tracking wildlife. I’d seen a manatee, a river dolphin, and a couple of new birds. When two guys in their twenties motored past in a pirogue, I didn’t pay them much attention. Ten minutes later, something slammed into my back and knocked me into the water. My arms were frozen stiff. I didn’t know what was going on. I kicked to the surface but didn’t see anyone. Then something hit my face. I used my head to push my kayak to the riverbank. I sat down and got hit again—someone was shooting at me from the jungle. I looked down and saw a pool of blood. I thought, This is where you are going to die. I lay down and closed my eyes.

When I opened them moments later, I saw one of the guys in the pirogue motoring toward me. I stood up and put my hands together like I was praying. “Please leave me alone,” I said, then kicked my kayak toward him. “Take it.” He just stared and headed upriver.

I ran. I got shot again, in the leg, but kept going. After five minutes, I saw two men on the opposite side of the river. I tried to yell, but nothing came out—the shots had damaged my neck and lungs. Eventually, they saw me and took me to their village, where everyone gathered around and whispered. I couldn’t feel the right side of my face or hear out of my right ear. My thoughts went all over. Then this old lady came up to me with a bucket of water and started cleaning the mud off my legs. That brought me back to the moment.

I asked to be taken downriver to a city called Pucallpa. The villagers made a wooden stretcher, wrapped me in blankets, and hauled me to a boat. A couple of hours later, we reached another village. It was night, and the only light came from torches and candles. The people there said to me, “Pobre, pobre”—poor, poor. I took the blankets off and said, “I have nothing to give you.” After about an hour, I started to throw up blood. They put me in a different boat. Throughout the night, I was passed along like this, from village to village. Late the next morning, I saw port cranes over the top of the canopy—Pucallpa. At the hospital, I reached my mom by phone, and she helped me get a flight to Lima.

I had 22 pellets in my body and punctures in my lung and carotid artery. I still can’t feel the right side of my jaw. Initially, I thought my survival was a testament to my strength, but lately I’ve realized it was because of the compassionate villagers who passed me down the river like a baton. —J.��.