YOUNG STEVE BLICK HAS BEEN COURTING A PLAYBOY PLAYMATE. He has wooed Miss April with flattering words, and now he kneels before her with gifts. In Blick’s duffel bag are a hundred pairs of Oakley sunglasses, with vaporized metal coatings and patented XYZ Optics. Blick does not wish to possess this woman in a physical way. He wishes to possess her in a marketing way: He wants to sponsor her bones.

The woman, 33-year-old Danelle Folta, is captain of Team Playboy X-Treme, an adventure-racing squadron that consists of 22 former centerfolds in their twenties and early thirties. Since its inception in 1998, Team Playboy has run one Eco-Challenge—the famously grueling slog across one or another of the world’s most unwelcoming landscapes—and nine Hi-Tec ���ϳԹ��� Races, daylong competitions here in the U.S. Unfortunately the team was disqualified in the 2000 Eco-Challenge for failing to reach a checkpoint in time, but placed second in the women’s division in four Hi-Tec races. The Playmates also compete in non-endurance events, including volleyball and golf tournaments. Regardless of their standing, the women feature prominently in television coverage of these games. To date, the team has 14 corporate sponsors, including Adidas, St. Pauli Girl, Red Bull, and Oakley. A popular ice cream brand is considering launching an X-Treme Girl flavor, despite the questionable tact of naming a lickable product after soft-porn models.

Blick, 33, has driven from Oakley’s Orange County headquarters to Santa Monica, where ten members of the Playboy team have gathered for a skills camp run by an outfit called ���ϳԹ��� Training Consultants. He has come to introduce the women to the sunglasses that they will be “running,” which is what Blick says instead of “wearing.” The group is standing in a corner of the parking lot outside the ���ϳԹ��� Training gym. Blick finishes his spiel, and the women descend on the black bag.

“Hey, Steve, what other fashion frames did you bring?”

“Steve, do you have any more like Danelle’s?”

“I can’t get my lenses in my M-Frame.”

“Mine won’t fit right on my nose.” Playmate Echo Johnson shows Blick how the frames hover above her provocatively upturned appendage. Blick fiddles with the frames and then tells her to try sliding them on over her hair, to which Johnson firmly replies, “No.” ���ϳԹ��� Training Consultants is owned by an affable 44-year-old triathlete named Scott Zagarino, who runs classes and training camps for endurance athletes. He periodically coaches the Playmates as they prepare for upcoming events. They’ve got several Hi-Tec races in the months ahead, along with their second Eco-Challenge, which takes place in Fiji in October.

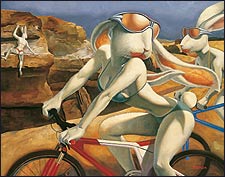

Zagarino is a Buddhist, but you can tell that his Zen is being stretched thin by the distraction Blick’s swag bag has presented. He has three days to cover rock climbing, sea kayaking, land navigation, and advanced mountain biking. Ten minutes ago, the ���ϳԹ��� Training van was scheduled to be on the road to Point Dume, a sea cliff a half-hour north of here. All around him, women in sunglasses are checking their reflections in other women’s sunglasses.

“You look awesome!”

“These are totally fly.”

“Can I try yours?”

Zagarino cups his hands to his mouth. “Can we please start moving toward the van!”

TEAM PLAYBOY X-TREME is a brilliant idea, but it wasn’t Playboy’s. It was Danelle Folta’s. Folta, a five-foot-ten redhead who likes to snowboard, wanted to use her celebrity to inspire women to get fit. She recruited 21 of her buffest centerfold friends, then lobbied parent company Playboy Enterprises for seed money. Playboy gave the team $100,000 and waived the licensing fee for use of the Playboy name, but that has been the extent of the formal relationship. Sponsors now pay for most of the team’s expenses. It is, as Playboy Enterprises communications director Bill Farley says, “a win-win-win situation.” Playboy gets exposure because of the team’s name, and the team gets exposure because they are Playmates. The networks that air the events get lots of viewers, and the viewers get to look at Playboy Playmates. It’s synergy at its best.

In 2000, three members of Team Playboy X-Treme decided to take on the mother of all adventure races, the Eco-Challenge. The 320-mile race, held in Borneo, involved three days and nights of kayaking, 30 hours of mountain biking, two days of canoeing, and two days of jungle navigation, along with miscellaneous skills like caving and extracting leeches from unspeakable places. The Eco-Challenge has always been a hit with TV viewers, in part because competitors don’t have to do much to qualify other than pass a few strenuous but rudimentary physical tests. As a result, catastrophes abound. There’s always someone getting lost in the jungle, suffering mental collapse, and/or requiring rescue at sea. Not coincidentally, the Playmates’ debut marked the first time the race was broadcast on the USA Network rather than the Discovery Channel. As the home of the World Wrestling Federation, the USA Network instinctively understands our national weakness for blood and boobs and cheesy human drama. Now that hapless adventurer could be someone who’s posed for a magazine in only pearls and high heels.

Since Eco-Challenge teams require four members and must be co-ed, Folta invited her friend Owen West, a 32-year-old former Marine and author of a swashbuckling military novel called Sharkman Six. Predictably, the cameras ignored Owen, though he still had a fine time: “I learned a lot,” he says, “and I’m a better man for it.”

Just as predictably, the other teams made fun of the Playmates. They were dissed for all manner of transgressions, in particular for wearing bikinis rather than Speedos for the swim test and for sucking up media attention even after they were disqualified halfway through for not reaching the biking checkpoint in time. (Though out of the race, the team decided to soldier on, showing the same pluck they had early in the competition when they hammered their outrigger canoe back together after a wave swept them into some rocks.) Some suspected that the team had received preferential treatment by the TV producers, who had good reason to try to keep them in the race. “I think many people were sympathetic toward them until they saw the USA Network’s program and couldn’t figure out where they got a hammer and nails [to fix the boat],” says Bev Abbs, a racer whose team was sponsored by a software company called Discreet. Competitor Rebecca Rusch reported that a rumor had been circulating that the Playboy team received not only repair equipment but also clean clothing and extra food.

In the end, many competitors wound up admiring the Playmates’ perseverance. “I was skeptical of them initially, because they acted more like bimbos than athletes before the race started,” says Maureen Moslow-Benway, a member of Team Booz Allen. “However, as the race progressed, I was impressed with their gutsiness. All in all, they’re good athletes deserving of the chance to compete in the Eco-Challenge. They got what most teams want—lots of publicity—and unfortunately, there’s sour grapes from some people who can’t deal with that.”

Folta and her team were in the awkward position that beautiful women often find themselves in: They were given special treatment because of their looks and then resented for it, despite the fact that they did not ask for or expect any help. Their looks are at once their greatest asset and their most frustrating liability. “People not in controversial roles don’t have to be on top of their games like we do,” says Folta. “I hope that doesn’t sound conceited, it’s just that people are more critical of our performance. Sometimes it feels like we have to work twice as hard. People don’t think you can do anything, but then you go out there and kick their butts.”

THE PLAYMATES are standing around the beach at Point Dume in “X-Treme Girl” T-shirts and lank ponytails and black sweatpants, waiting for the climbing instructor to arrive. Their sweatpants are unlike any I grew up with, in that they have bell bottoms and cling provocatively to the buttocks and thighs. No one has panty lines. The women are well toned, but you wouldn’t call them muscular. The main thing that sets them apart from the average female athlete is, well, their breasts. You could fill a set of C cups with an elite female athlete’s calves, but rarely with her breasts, owing to changes in lean-fat ratios and estrogen levels during intensive training. None of that going on here.

Folta is the only one who trains and competes full-time. The others are models or artists or moms. They don’t claim to be hard-core. They are just gals who love the outdoors, love sports, love travel and camaraderie, and love having sponsors pay their way. The team’s collective sports résumé includes mountain biking (22 of 22 women), distance running (12), in-line skating (10), and snowboarding (11).

Only five of the ten women here today have tried technical rock climbing, partly because it’s rarely included in adventure races. They will learn how to tie in to a climbing harness, attempt a 5.6 route, rappel back down to the beach, and attempt a second, 5.9 route. It’s an ambitious plan for one day. When I took introductory rock climbing, the course lasted two days and culminated in a 5.5 climb that a quarter of the class failed to finish.

The instructor, Tom Magee, has arrived and is unloading gear. He turns to the women and says “Who’s worn a harness?” with absolutely no trace of a smirk. Magee is a former body-builder and WWF wrestler, a man who has answered, at various turns, to both “Mr. British Columbia” and “Joe MacKenzie, the Cruel Canuck.” These days Magee is heavily involved in climbing.

The former Mr. British Columbia kneels down to help the former Miss January, Echo Johnson, with a leg strap. Like everyone else on Team Playboy X-Treme, she has a well-turned sofa-bolster ass and enviable thighs. The harness sets off the sofa bolster in a fetching manner. Although I have worn a climbing harness before, the similarity to a garter belt has heretofore escaped me.

One after another, the women climb the 5.6 arête as though it were the escalator at Nordstrom on a 40-percent-off day. They are clearly strong and seemingly fearless. The ones waiting their turn sit on the sand, talking and gossiping (“That female wrestler grew a penis from taking steroids!”) and feeding sound bites to the two TV cameras that have shown up. A reporter from Channel 13 News tells Folta that his station is doing “a story on hot women who do extreme sports,” which she relays to the team as “a story on cool women in sports.” Either way, Channel 13 has an interesting concept of news.

On the ground, Playmate Victoria Fuller, blond and sultry-eyed, is talking to her teammates about a disastrous modeling shoot. “You should have seen what they had me in. The makeup people were laughing at me. Then the stylist took half my hair down. I looked like Predator.”

To hear the Playmates tell it, nude modeling can be as X-Treme as much of what they do on the team. One recalls a Playboy shoot during which wooden props had to be made for her feet because her legs were cramping from being on tiptoe too long. “Basically,” Deanna Brooks explains, “if it’s uncomfortable, it looks good. ‘Arch your back, put your chest out, now twist 45 degrees, now reach up and stick your hand in your hair…'” To the near-palpable disappointment of the Channel 13 man, she does not demonstrate.

Another hour passes as the women take turns on the cliff. Some start eating lunch. Jennifer Lavoie, a compact, high-wattage Playmate who now designs handbags, picks a veggie sandwich out of the cooler and then abandons it for tuna, crying “Gimme some meat!”

The Playmates do not eat like models. They work out too hard to be on diets. I asked six of them about their regimens and all reported daily or near-daily trips to the gym. Lavoie, who was on the 2000 Eco-Challenge team, e-mailed me her schedule: “Monday: 60-minute lift and 30-minute cardio. Wednesday: 45-minute lift, 60-minute spin class. Thursday: 60-minute Butts & Guts class, 25 minutes cardio, 60-minute yoga class. Friday: 60-minute lift, 20-minute cardio. Saturday: 35-minute swim, 60-minute spin class. Sunday: 60-minute lift. Tuesday is my off-day.”

Team captain Folta’s prerace regimen consists of six to 12 hours a day in the gym and on the bike and a 20-hour training session every other week. For multiday adventure races, she adds one 40- to 50-hour training session to “make sure I know how the team will cope with sleep deprivation and exhaustion.”

Because she and the Playmates lack mountaineering skills, Folta decided to skip last year’s Eco-Challenge, which took place in New Zealand. “We’re not a cold-weather team,” she says. She admits that they might miss this October’s Fiji race, too, if a deal goes through to produce a Team Playboy X-Treme TV show, the rights for which have been purchased by Endemol, the company that brought you the ogle-fests Fear Factor, Spy TV, and Big Brother.

While the women eat, I ask them what they find to be the most challenging aspect of Team Playboy X-Treme. Most of their answers have to do with not being taken seriously as a competitor. I listen and offer words of understanding, and then I ask about their chests.

Do exceptionally large breasts handicap an athlete? Not really, is the consensus, though Lavoie confesses to wearing two sports bras at once and Nicole Woods has trouble with her golf swing. Folta says tartly: “If you were interviewing a male athlete, would you ask him if an exceptionally large package hinders him in his sport?” I reply that no, I wouldn’t, unless his team were called, say, Team Playgirl or Team Clydesdale Penis—and then you bet I would. To make it up to Folta, I tell her I will pose the question to the next well-endowed athlete I come across. This is a lie, because that athlete would be Tom Magee, who is wearing a climbing harness, which does for packages what push-up bras do for bosoms, and I cannot bring myself to say it.

From high above, we hear a strident, agitated sound. Seagull? Police car? No, it’s Victoria Fuller. Fuller has never climbed before. Three-quarters of the way up, she is plastered to the rock, arms and legs splayed like Wile E. Coyote. The women shout encouragement, and, as if powered by their collective will, Fuller reaches the top. Now she must rappel down—or, as one woman puts it, “propel” down. The team’s mastery of climbing lingo has been the one thing that marks them as beginners. “On belay!” has variously come out as “On Vuarnet!” and, in a moment recalling the late Teddy Roosevelt, “Bully!”

The rappel requires Fuller to lean against her harness, step backward off the small ledge, and trust her fate to a strange man 70 feet below. She flaps her hands and lets out a long “Noooooo!” This devolves into a scream that provokes looks of alarm and forces a retake of the Channel 13 tagline (“See Playboy’s X-Treme Team like you’ve never seen them before!”). Coaches Magee and Zagarino decide to hike up the trail on the back side of the cliff, haul Fuller up the remaining five feet of the wall, and escort her back down. Folta intervenes. “Vic’s just veryÉcommunicative. She’ll be OK.” With shouts of support from her teammates, Fuller eventually makes it down, dignity and French manicure more or less intact.

By 3 p.m. the women have moved on to the 5.9 route. All of them make it at least halfway, and most make it to the top. By any standard, it’s an impressive performance. Magee smiles broadly.

“These girls are risk takers,” he says.

“Climbing a rock face and taking off your clothes both go against your natural instincts. I knew they’d kick ass.”