H2O is what connects us—it’s the alpha liquid that supports natural wonderlands and lets us live, play, and explore. You’d think we’d be taking better care of this critical resource, and yet waste and pollution are rampant and more than 1.1 billion people lack access to clean water. The good news? Our special report introduces you to the water heroes who are reversing the worst woes and showing us how to keep the planet afloat.

Troubled Waters I

The globe's six biggest water crises—and what's being done to conquer them

Down the Drain

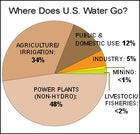

Americans use more water per capita than any other nation on earth. Here’s where the gallons go:Flushing toilet: 3┬ľ5

Low-flow: 1.6

Brushing teeth 1 min., faucet running: 4

Low-flow, off while brushing: 0.2

Washing dishes by hand: 25

Water-wise dishwasher: 6

Washing car 10 min., hose running: 100

commercial car wash: 32

Water Shortage

1. Access Denied

STATUS: For a huge percentage of earth's population, turning on a faucet would be as miraculous as turning water into wine. That's because 1.1 billion people don't have access to clean water, and two-fifths of the world's inhabitants┬Ś2.6 billion people┬Ślack access to sanitation facilities, resulting in regular exposure to human waste, particularly in local water sources. The deadly result: As many as five million people a year┬Śmost of them children┬Śdie from waterborne maladies like cholera, typhoid, dysentery, hepatitis, and diarrhea, which by itself is estimated to kill one child every 15 seconds.

According to some studies, 80 percent of the developing world's health problems are related to contaminated water. “It's not a supply or technology issue┬Śthere's clean water all over the world,” says Ted Kuepper, executive director of Global Water, a California-based nonprofit. “It's a matter of getting it to people.”

SOLUTION: Simple gravity-fed spring-catchment systems, $10,000 to $20,000 each, can transport clean water to villages within a few miles of natural springs; these work well in places like Central America. In drier climes, wells are often the only source of clean water, though rainwater-collection systems can also be used. Simply providing villages with communal taps and latrines can reduce disease by more than 75 percent.

And they're hot causes, too. Hip-hop mogul Jay-Z recently filmed an MTV documentary on water issues, and while shooting a movie in the Sahara last year, actor Matt Damon created the H2O Africa Foundation, to bring water access to the filming locations in Senegal, Mauritania, Mali, Libya, and Egypt. But the United Nations has the most ambitious mission: One of its Millennium Development Goals is to cut in half by 2015 the number of people without access to clean water and basic sanitation, a goal the World Health Organization says could cost $11.3 billion per year.

2. Oceans in Peril

STATUS: Big blue is in deep trouble. Fish populations are tanking due to overfishing (a recent study in Science estimates that by 2048 there will be no commercially harvestable seafood left), and pollution has created about 200 deoxygenated areas in places like the Gulf of Mexico, where there's a New Jersey-size dead zone in summer. Meanwhile, bottom trawling, in which nets are dragged along the seafloor, is destroying fragile ecosystems like coral gardens, and longlines are snagging animals like turtles and albatrosses, decimating their populations. Overdevelopment is imperiling coastlines, and CO2 emissions, which concentrate carbon in the water and wreak havoc with pH balances, are causing ocean acidification, which could destroy a vast spectrum of sea life┬Śfrom diatoms to oysters to coral reefs.

SOLUTION: For ecologist Carl Safina, founder of the Blue Ocean Institute and a MacArthur fellow, the global priority right now is restoring marine wildlife, making fish populations as healthy as possible. In this regard, the U.S. has a good track record: From the 1996 Sustainable Fisheries Act to the creation of no-fishing-allowed reserves┬Śsuch as last June's establishment of the 137,792-square-mile North-western Hawaiian Islands Marine National Monument┬Śthe nation is giving fish a fighting chance. “The U.S. has a whole suite of recovering species┬Śstriped bass, king mackerel, summer flounder, and swordfish,” says Safina. Worldwide, there are some similar moves to create reserves, such as the 71,000-square-mile Phoenix Islands Protected Area, near Kiribati. But the vast majority of coastal waters still have few or no protections.

The silver lining? “Oftentimes it takes a sense of crisis to get countries and individuals mobilized,” says Josh Reichert, director of the environmental division of the Pew Charitable Trusts, whose focus includes ocean health. “And we are now faced with a crisis.”

3. Mass Pollution

STATUS: Toxic sludge. Raw sewage. Animal excrement. Deadly farm chemicals. All of these ingredients find their way into the world's water supply. In developing nations, as much as 90 percent of sewage and 70 percent of industrial waste pour into local waters without any treatment whatsoever. Even in the U.S., sewage pollution is problematic. “Most treatment plants are old and inefficient, and their technology is from 1916,” says Nancy Stoner, a senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council. If fixes aren't made, she warns, “by 2025 we can expect to have as much sewage pollution as we had in 1968, before the Clean Water Act.”

But agriculture is the crisis at our doorstep. Irrigation runoff and massive amounts of animal waste from factory farms┬Śthe nation's top water-pollution sources┬Śhave fouled more than 173,000 miles of waterways.According to Worldwatch Institute, once contaminants reach groundwater, they are “essentially permanent,” since onaverage they remain there for 1,400 years.

SOLUTION: “Primary and secondary treatment of waste is the most inexpensive thing we can do,” says Paul Faeth, former managing director of the World Resources Institute, an environmental think tank with a focus on water. That means building water-treatment plants and cleaning up industrial waste around the world, an effort led by groups like the Global Water Partnership, an international network of water agencies that connects developing nations to technical expertise. In the U.S., Maryland and other states around the Chesapeake Bay have reached a comprehensive agreement to clean up the bay and have already restored more than 3,000 miles of natural streamside buffer zones to filter toxins and fertilizers that would otherwise seep into the Chesapeake. Bad practices on factory farms┬Śwhich hold animal waste in lagoons or spray liquefied manure on crops┬Śhave been successfully fought on the state and county levels, and a 2003 lawsuit brought by the Natural Resources Defense Council, Sierra Club, and Waterkeeper Alliance against the Environmental Protection Agency has forced the federal office to put some teeth into its factory-farm rules. The EPA is now hashing out new permit requirements that will likely go into effectthis summer.

Troubled Waters II

The globe's six biggest water crises—and what's being done to conquer them

Water Shortage

SOURCE: USGS

SOURCE: USGS4. Climate Change

STATUS: You've heard all about the earth's water cycle: It rains, rivers flow to the sea, water evaporates and forms cloud vapor, and then it rains again. It always sounded so predictable. Well, hold on to those galoshes, because that stable system is likely to go bonkers, according to climate forecasters. If, as expected, the earth's temperature rises between about three and seven degrees Fahrenheit in this century, the result will be more evaporation and more water vapor, which itself acts as a potent greenhouse gas, accelerating global warming. Essentially, the whole hydrologic cycle may act like it's on speed, sparking fiercer and more frequent storms and flooding, melting snowpack and glaciers, and threatening the water supply of one-sixth of the world's population. Sea levels could rise up to two feet by 2100, drowning cities, wetlands, estuaries, mangroves, and other ecosystems, not to mention a few of your favorite tropical atolls. In turn, the destroyed wetlands would no longer absorb greenhouse gases, feeding an ever more vicious cycle.

SOLUTION: Reduce global emissions of greenhouse gases as soon as possible. “The longer we wait, the graver the risks and the cost of averting them,” says Eileen Claussen, president of the Pew Center on Global Climate Change. Groups like Pew are building worldwide coalitions to support treaties and policies like emissions cap-and-trade programs, which set a limit on the amount of CO2 allowed to enter the atmosphere. Such market-based approaches, perhaps combined with a tax on emissions, would provide cash incentives for industries and individuals to adapt more quickly to a low-carbon reality. In January, a coalition of environmental groups and industrial giants like DuPont and Alcoa proposed reducing emissions by 10 to 30 percent over 15 years. And energy guru Amory Lovins insists that clean alternatives, like hybrid cars and low-carbon fuels, are already available or in the pipeline. “Existing efficiency technologies, systematically applied, can save half of our oil and gas, and three-fourths of our electricity,” he says. “This by itself would solve nearly half the climate problem.”

5. Excess Dams

STATUS: The Tinkertoy lovers among us may admire their engineering, but dams are the most perilous threat to river systems worldwide. Consider the numbers: 47,655 large dams exist today in 140 countries; they're present on 60 percent of the world's major rivers; and the weight of their water is so immense, it's believed to have altered the speed of the earth's rotation. Dams also supply one-fifth of the world's electricity and help irrigate about one-sixth of the world's food, but the benefits come at a huge cost.

As many as 80 million people have been displaced by dams worldwide, including nearly two million Chinese living above the new Three Gorges Dam, on the Yangtze. Dams prevent fish migration, causing local extinctions; they alter river flows and water temperatures, killing plants and aquatic species; and they destroy habitats and recreational areas. (Paddlers, take note: Not even 2 percent of U.S. rivers today are free-flowing.) Big dams are also a wasteful way to store water┬Śhuge reservoirs suffer so much evaporation that they can lose up to 10 percent of their volume each year.

SOLUTION: World leaders and enlightened governments are putting proposed dams┬Śand even existing ones┬Śto the test: Are they worth it? While small hydro projects can be a green boon, since they provide clean, renewable power, most large dams are not. “In many cases, it's clear that the negative impacts of dams outweigh the benefits,” says Patrick McCully, director of the International Rivers Network and member of the UN's Dams and Development Project. That new vision is especially noticeable in the U.S., where experts say the era of big-dam building is over. More than 212 dams have been torn down in recent years, with glowing results: When the Edwards Dam came down on Maine's Kennebec River in 1999, schools of migratory alewives returned by the hundreds of thousands. Where knockdowns are not an option, dams can often be better managed┬Śfor example, dam operators can release more water during dry seasons, to help fish and downstream wildlife. The Nature Conservancy has partnered with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to tweak water releases through 27 dams in nine river basins so far, with more agreements on the way.

6. Lost Habitats

STATUS: As humans pave paradise, expand cities and farms, and suck up more water┬Śand pollute what's left┬Śwe leave individual species and entire ecosystems at risk. Topping the endangered list: freshwater ponds, lakes, streams, rivers, and marshes. Already, about half the world's mangrove ecosystems (critical for spawning fish, sheltering birds, and recycling nutrients) and half of its freshwater wetlands┬Śhome today to an estimated 40 percent of the earth's species┬Śhave been lost to development. Some 75 percent of the globe's fish stocks have been nearly or totally depleted, and more than 20 percent of freshwater fish species have become extinct, endangered, or threatened in recent decades.

Statistics aside, nearly every terrestrial species is in some way dependent on freshwater ecosystems for their survival┬Śhumans included. Wetlands and bogs filter and cleanse water, regulate water flows, absorb storm surges, and protect us from hurricanes. These natural services, provided free of charge, can offer more of an economic boon to communities than developing the wetlands would. “We need to recognize that freshwater ecosystems have economic value, and we need to set some boundaries,” says Sandra Postel, director of the Global Water Policy Project.

SOLUTION: Rivers and wet-lands can be forgiving: Many will bounce back if you simply keep enough water flowing in them. And U.S. courts are increasingly ruling that “in-stream flows”┬Śwater that in the past was often sucked out of rivers for irrigation or urban use┬Śmust be protected for the health of fish and other fauna. Conservation groups and citizens' coalitions are also working to take back aquatic zones. Ducks Unlimited is helping preserve wet-lands on two million acres, stretching from Canada and Montana to Minnesota and lowa, by plugging old drainage ditches and letting ponds and marshes refill. In Brazil's Pantanal, the earth's largest wet-land, activists are successfully fighting a massiveshipping waterway. And worldwide, members of the Waterkeeper Alliance, a grassroots group with more than 150 chapters, use patrol boats to monitor polluters, then take the worst of them to court.

╠ř

╠ř

╠ř

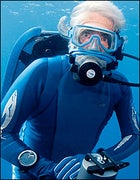

Jean-Michel Cousteau

Podcast and Gallery

and see he and his son Fabien and daughter Celine in action in our exclusive online gallery.Jean-Michel Cousteau

Carrie Vonderhaar/Ocean Futures Society

Carrie Vonderhaar/Ocean Futures Society

Podcast: Listen to an interview with Jean-Michel Cousteau

The new patriarch of the first family of the sea, Jean-Michel, 68-year-old son of the legendary Jacques Cousteau, is founder and president of the Ocean Futures Society, a nonprofit dedicated to ocean conservation and education. And he’s making waves. Last year, an episode of his PBS series Jean-Michel Cousteau: Ocean ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°s influenced President Bush to create the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Marine National Monument, the largest protected marine area on earth. Next, he’s off to the Amazon to document the region’s global importance.

“Since my father pushed me overboard with a tank on my back at the age of seven, I’ve been completely engulfed in the aquatic environment. The quality of our lives is directly linked to the quality of water: no water, no life. We’ve been very lucky because nature has been doing a fabulous job of cleaning itself. But there’s a point when nature says, ‘Too much is too much.’

Greg MacGillivray

Greg MacGillivray

Shaun MacGillivray/MacGillivray Freeman Films

Shaun MacGillivray/MacGillivray Freeman Films

Podcast: Listen to an interview with Greg MacGillivray

Greg MacGillivray, 61-year-old cofounder of Laguna Beach, California┬ľbased MacGillivray Freeman Films and director of the 1998 Imax hit Everest, is as passionate about water conservation as he is about filmmaking. Next up is Grand Canyon ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° 3D, a film made in partnership with Teva and the Waterkeeper Alliance, set to debut in March 2008. It’s a rollicking Colorado River raft trip and stunning plea for action that stars water activist Robert F. Kennedy Jr., kayaker Nikki Kelly, and anthropologist Wade Davis.

“I love the ocean; growing up around Laguna Beach, I spent my summers surfing, diving, and snorkeling. But over the past few decades, I’ve noticed a remarkable change in California’s aquatic environment. So I’ve been using the power of the Imax medium, with its gigantic screens and supervivid pictures, to get people to fall in love with the ocean. Now the world is moving toward a water crisis. What’s happening on the Colorado River is happening all over the world. The water is overused, overdammed, and it’s polluted in some places. My goal is that after seeing Grand Canyon, every person in the audience will go home knowing they have to conserve water┬Śeven something as simple as installing a low-flow toilet or showerhead, or turning off the faucet while they’re brushing their teeth. We go through life so wastefully now; if we can just alter our behavior a tiny bit, it would make a tremendous difference.

Aqua Man

Environmentalist Robert F. Kennedy Jr. is always on the H2O front lines

It’s no surprise that RFK Jr. cares passionately about water—he’s been sailing,fishing, and paddling since childhood. But what he’s accomplished with that passion is astonishing. Simply put, the iconic Kennedy—master falconer, avid kayaker, and son of the late senator Robert F. Kennedy—is one of the leading environmental advocates of our time. He’s the chief prosecuting attorney for Riverkeeper, a nonprofit group devoted to protecting New York’s Hudson River watershed, and president of Waterkeeper Alliance, an international network of water defenders. He’s also the senior attorney for the Natural Resources Defense Council and co-author—with acclaimed New York water warrior John Cronin—of The Riverkeepers. Along the way, Kennedy, 53,has helped command one of America’s brightest eco-successes: the cleanup of the Hudson, whose now swimmable waters were once largely a liquid garbage bin. But his most recent book, Crimes Against Nature—a takedown of the Bush administration’s environmental record—perhaps best highlights his core belief: that our obligation to nature is a moral one, the shunning of which harms not only the future but the very fabric of society. Senior editor AMY LINN spoke with him about his crusade.

OUTSIDE: What made water issues such a calling?

KENNEDY: I spent most of my early life wandering the creeks around my home in Virginia and spending summers on the Cape, fishing almost every day. On vacations my father would take us to the whitewater rivers. We ran the Salmon, the Snake, and the Colorado, the Yampa, the Green, and the upper Hudson. And I always understood that water wasn’t just an environmental issue; it was a civil-rights issue—a human-rights issue. The best way of measuring the success of a democracy is how it distributes the goods of the land—the commons.

Did you see threats long ago?

I couldn’t swim in the Hudson or the Charles or the Potomac when I was growing up. I was shocked, when I ran the upper Hudson, when the guides told us it was poisonous to drink. And I always recognized that as an act of theft—that pollution was a theft. It was the act of a big shot with political clout stealing from the rest of us—stealing publicly owned resources from the public.

What’s at stake?

The relationship with nature is so critical to our culture. We’re not protecting nature for the sake of fishes and birds. We’re protecting nature for our culture, for our prosperity, for our quality of life.

And if we want to meet our obligation as a generation, as a nation, as a civilization—which is to create communities for our children that provide them with the same opportunities for dignity and enrichment and good health as the communities that our parents gave us—then we’ve got to start by protecting our environmental infrastructure. We’ve got to protect the air we breathe, the water we drink, the wildlife, the public lands, the waterways that enrich us, that connect us to our past, that provide context to our communities—and that are the source, ultimately, of our values and virtues and character as a people.

How does a Waterkeeper help?

Every Waterkeeper has a patrol boat on the water. We also take the public out, and take journalists out. We do this to constantly remind the public that this is their property. The polluters want to make the public think the waterways belong to them—that they’re just a waste conveyance.

Is there a way to bring the message close to home?

If General Electric pulled a truck up to your lawn and dumped PCBs into your yard, you would fight them until they removed the last molecule. So why don’t we react the same way when they dump PCBs into our river?

What’s the most important thing people can do?

They have to be willing to fight—that’s all. You have to be willing to fight.

For more on water, visit or .

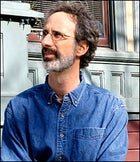

Peter Gleick

Peter Gleick

MacArthur fellow Peter Gleick, 50, is a leading water expert and president of the Pacific Institute, in Oakland, California, and edits The World’s Water: The Biennial Report on Freshwater Resources.

“The fact that this is the 21st century and we’ve failed to meet basic human needs for water is the most appalling problem facing us. It’s our most egregious failure. We’re not living in a world where our demand for resources has to go up inexorably. Clean water is finite, but it’s renewable if we’re careful. The problem is that we don’t use it properly and don’t plan our systems properly. If we did, there would be enough to meet everyone’s needs. We give it inadequate attention, inadequate funding, and┬Śall too often┬Śincompetent governance. It’s a problem of will and commitment. I originally came to the subject through an interest in energy issues, but I’m drawn to water now because it’s so critical to everything we care about: the environment, prosperity, family life. If any other environmental problem is more connected to all aspects of our lives, it would be hard to imagine what that is.”

Dean Kamen

His mind-boggling purifier could save millions of lives

Dean Kamen

Dean Kamen, 55, is probably best known for inventing the two-wheeled Segway people mover. But his latest creation promises to move mountains. The device, dubbed the Slingshot, can transform the filthiest water into pure, drinkable H2O. The 300-pound, electric-powered, dishwasher-size prototype purifies both freshwater and saltwater, basically by vaporizing, compressing, and condensing the liquid. At Deka Research & Development, his Manchester, New Hampshire┬ľbased company, Kamen’s standing challenge is this: Bring him the vilest goo and he’ll run it through the Slingshot, knock it back, and ask for more.

║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°: How much faith do you have in this machine?

KAMEN: Last summer we took one into Tiananmen Square, in China, and fed it local river water. It was not only brown and disgusting; it was gelatinous. It had stuff bobbing around in it that would almost defy description. And out came the cleanest, purest water you’ve ever had. We were standing around handing it out to people in paper cups.

How did you get interested in water in the first place?

We at Deka were designing home-based dialysis systems┬Śwhich require water clean enough to inject┬Śso we were very interested in how to purify local water. Even in the developed world, tap water can have arsenic, cryptosporidium, lead, and other contaminants, so we spent millions trying to figure out everything that could possibly go wrong with water and how to fix it. Eventually I said, hey, we could help a few hundred thousand people┬Śor we could expand this technology to serve a billion people around the world.

Did everybody immediately say, “Great idea!”?

Everybody said “You’re nuts!” But I thought, If we can manufacture a machine that has no need for chemicals or activated charcoal or membranes┬Śand if we can create something small and rugged enough to carry into remote areas and have it run for years with no maintenance┬Śwe’d solve the problem.

You recently tested a prototype in Honduras, where people were getting sick from drinking dirty river water. How did it go?

From day one we were making a thousand liters a day. People loved it. Now we’re ready to go with more prototypes in other villages next year. In a few years we hope to have them widely available. In very high volume, they’d be under a few thousand bucks apiece.