Map of Antarctica

Antarctica

AntarcticaJabet Peak summit

Binning and Hagen on the summit of Jabet Peak

Binning and Hagen on the summit of Jabet PeakSphinx, Antarctica

Earn your turns: An expedition team moving up an ice cliff on a steep face they named the Sphinx

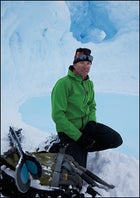

Earn your turns: An expedition team moving up an ice cliff on a steep face they named the SphinxChris Davenport Davenport

Davenport

DavenportAustralis, Drake Passage

The Australis in the Drake Passage

The Australis in the Drake PassageAntarctic Expedition

Davenport, Workman, and the author

Davenport, Workman, and the authorChris Davenport, Antarctica

Davenport skiing an iceberg

Davenport skiing an icebergTWO HUNDRED THOUSAND TONS of freshwater go into making your bigger Antarctic icebergs. They’re formed when ice calves off a glacier or an ancient frozen shelf. Splashing into the salt water of damned-cold seas, icebergs drift off on their own, sometimes covering ten miles a day. Less dense than salt water but not by much bergs float like pear-shaped tubbies at the Jersey Shore, with 10 to 15 percent poking above the surface and a great rumpy mass below.

At the moment, a medium-huge berg roughly the size of a large yacht is minding its own business in Waddington Bay, a body of water off the north side of the Antarctic Peninsula, that spindly geographic thumb that points toward South America. Suddenly, an intruder starts hacking into its blue-white mass with a pair of ice axes. The blades belong to 39-year-old American Chris Davenport, a former World Extreme Skiing champion who’s now a multi-sponsored, globally known ski mountaineer. Davenport swings his ax points into the ice. He kicks his way up it wearing ski boots. Hauling a pack with skis, he spiders up a wall that angles steeply into the bay.

Before long, he reaches the berg’s 100-foot “summit,” detaches his skis, lays them down carefully, and clicks into his bindings, knowing that it’s not necessarily smart to ski an iceberg. Davenport’s body weight and gear are putting 200 new pounds on top of its unstable apex. He and his fellow ski adventurers Australian Andrea Binning, 33, and Norwegian Stian Hagen, 35 have watched from afar as a few top-heavy bergs actually flipped over, with a thunderous splash. Sometimes the bergs simply implode and sink. The sounds of disintegrating chunks are echoing freely throughout the bay, and Davenport will tell me later that when he skied this berg, which he did twice, he could hear it groan.

So why is he doing it? The answer isn’t much more enlightening than the old dog-licks-self truism: because he can. One skis icebergs in Antarctica precisely because you can’t ski them in Verbier or the Khumbu. But the stunt is really just garnish to this trip’s main event: skiing several of the dramatic, snow-covered spires that erupt out of the hyper-clear waters around here.

“The Antarctic Peninsula is the last great ski location on earth,” says Davenport, who ought to know. In 2007, the Aspen-based athlete became the first person to ski all 54 of Colorado’s 14,000-foot peaks in a year. Along with Hagen who cut his teeth on the icy couloirs of Chamonix Davenport has also knocked off Europe’s most intimidating ski descents, including the Eiger, the east face of the Matterhorn, and Mont Blanc.

The basic plan this time: float in from Ushuaia, Argentina, on a 75-foot sailboat called the Australis, ride inflatable, outboard-powered Zodiacs to rocky beaches, climb peaks, and then relish descents that have probably never seen skis, moving cautiously because of the scary absence of paramedics and rescue helicopters.

“People have scoured the globe for the next Valdez,” Davenport says, but almost no place can match Alaska’s combination of huge peaks, maritime snowfalls, and opportunities for untouched lines. Antarctica just might. “The Antarctic Peninsula is like the Southern Hemisphere’s answer to AK,” he adds, “even though it’s a lot harder to get to.”

SOUNDS GREAT, DOESN’T IT? Wouldn’t you love to be with us, seeing these uncharted playgrounds for yourself? Not to worry: A major part of our mission just as important, really, as bagging first descents is to make you feel like you’re here.

A modern adventure has many moving parts, and they come in two basic categories: the gear the athletes use to perform their feats of derring-do, and the gear they use to tell the world all about it. It adds up to a lot of stuff. Our crew contained less than a dozen people, but between us we had enough equipment, clothing, and communications hardware to bury ten luggage carts back at the Buenos Aires airport, prompting a hysterical Argentinian woman to light into Davenport for being a cart hog.

But what could he say? Expedition and film crews travel heavy Davenport paid $1,800 in excess baggage fees for all the duffels, ski bags, and Pelican cases we’d brought and the footage guys, who are indispensable, have their own hefty loads. Onboard with the three pro skiers are Ben Wallis, the rugged Australian skipper of the Australis; Skye Marr-Whelan, our first mate (and Ben’s girlfriend); mountain guide Doug Workman; a magazine writer (yo!); and three professional image makers: still shooter Greg “GVD” Von Doersten and two videographers, Jim Surette and Scott Simper, who are filming a documentary called Australis: An Antarctic Ski Odyssey. GVD, for his part, is hauling four cameras, two water housings, and 100 gigs’ worth of CompactFlash cards to earth’s most remote continent.

��

In the modern era, trips like Davenport’s happen only because a group of sponsors decide it’s worth their while to send talented jocks off to do something difficult, and they want plenty of images for their money. The marketing payoffs are impossible to calibrate do accountants look for a revenue surge when the team is hunkered down in a homicidal blizzard? but people in the outdoor biz seem to agree that these investments are a good idea. According to Jon Atencio, athlete manager for the Amazon.com of the crampon set, based in Park City, Utah underwritten expeditions make everybody happy.

“We sponsor athletes because they’re doing things that the average Joe in his cubicle only dreams of,” he says. “We have massive subscribed e-mail lists, and it’s nice to alert people to a big adventure, instead of just saying, ‘Scarpa boots on sale!’…Goodwill is part of it. It’s not like we see a sales spike for mountaineering in Antarctica. We don’t get a sales spike even if one of our athletes does something amazing on CNN. The value of sponsorship to us iscredibility. We can say, ‘We’re a core company supporting core athletes on core adventures.’ “That doesn’t mean the companies throw money at any old expedition, especially during arecession. To cobble together the roughly $90,000 cost of this trip, Davenport started beseeching sponsors back in early 2009, armed with a four-page, full-color proposal called “Australis: An Antarctic Ski ���ϳԹ���.” It read, in part, “The objective of this expedition is to climb and ski first descents in one of the world’s last great unexplored ranges, the Antarctic Peninsula. Our professional film crew will capture HD Video…to produce a feature-length ski documentary…. Only a handful of ski groups have explored the range, and very little documentation of skiing has been accomplished there. We would be the first team to bring the beauty and majesty of the Antarctic Peninsula to the modern ski-film viewer.”

Davenport sent Helly Hansen the main clothing sponsor for both him and Hagen a request for $30,000. In a pitch target=ed to Backcountry.com, he stressed the particular benefits of the film he hoped to make. “I would like to offer Backcountry.com a multi-faceted sponsorship opportunity for this film project,” he wrote. “What I need…is an additional budget of $15,000 to be spent on the post-production…including editing, transfer, music, color-correction, and DVD printing. Backcountry.com would get opening sponsor credits with logo in the film, as well as more subtle product placement (stickers and coffee mugs come to mind). I would provide Web dispatches and photos from the expedition to Backcountry.com. I would also offer that Backcountry.com would be able to stock, sell, and promote the DVD when it becomes available in late summer 2010.”

The company which has been resoundingly successful, even in a bad economy went for it. So now on Backcountry.com, you can link directly to Davenport’s blog. (Davenport is listed, along with 32 other Backcountry.com athletes, under the heading “Pro Team.”) Once you arrive at , you’re shown the Antarctic dispatches, then tempted by a boomerang link: “Check Out Chris’ Gear: backcountry.com.”

Throw in Hagen’s and Binning’s sponsors (Roxy, Black Diamond, Adidas, Völkl, Marker, and others) and you’ve got capital-A ���ϳԹ��� in the 21st century: a mission in which photogenic, gender-balanced, multinational teams do their thing in undiscovered glory holes. Nailing big and/or weird objectives is a particularly favored niche, producing oodles of imagery that will thrill the core audience watching various magic-glow boxes back home.

WE LEAVE USHUAIA on November 22, sailing through the Beagle Channel as we begin a four-day voyage from the southernmost city in the world to Antarctica via the Drake Passage, 600 miles of stomach-churning pitches and yaws. As the warm evening sun glints off the Australis‘s wake, we glide through the channel, below snowcapped, arrowhead-shaped peaks. But the fun stops once the protected channel opens into the wide-open Drake. Even with the aid of seasickness patches, people go green and puke. I’m queasy myself, unless I stay flat and motionless in bed which itself is not without hazard. After one especially violent wave, Workman launches from his upper bunk, rolls across the hall, and bangs into a metal ladder on the other side. This wakes him up.On Thanksgiving Day, we anchor safely in the Melchior Islands a rocky archipelago near the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, which has been called “the Venice of Antarctica” because of its endless channels and natural canals. The next morning, we get down to business, bagging a line on 1,788-foot Jabet Peak, on Wiencke Island. It feels carnal to move legs on land again after five days at sea.

@#95;box photo=image_2 alt=image_2_alt@#95;box

We change our ascent route after spotting a hidden, 1,000-foot couloir rising almost to the summit. Near the top of a long, hard climb, Davenport asks, “Do we chance a really steep descent on the south face?” We do, because it’s in the sun, and because the visuals will pop. “Really steep” turns out to mean 52 degrees as thoroughly modern adventurers, Davenport and Hagen have inclinometer apps on their iPhones. Committing to a ski turn on a pitch that steep takes a leap of faith. Once moving, though, we experience perfect backcountry conditions: smooth and predictable.

It was a triumph except for one glitch: We left all our sunscreen on the boat, thinking our base tans would be enough. Wrong. We came back looking like we’d been for a stroll on the surface of Mercury.

There are other little headaches. Davenport has borrowed an Inmarsat BGAN satellite terminal to provide us with wireless Internet access. The idea is to send dispatches to Backbone Media, a Colorado-based PR firm, which will then file posts for Davenport’s personal blog, as well as updates for the Web sites of sponsors Black Diamond, Red Bull, Backcountry.com, Kästle skis, and Smith Optics. But the BGAN is fickle. Mountains (and even icebergs) disrupt its signal. Scrambled software forces Davenport to speak to an IT dude for 15 minutes on a dollar-per-minute sat phone. The last few days in Antarctica, the BGAN refuses to work at all. Internet communication dwindles to sketchy, early-nineties levels like we’re all still on CompuServe.

��

It’s a big blow. Sponsors pay for adventures because they can’t entrust all their salesmanship to the pimply teens at your local ski shop. From a trip like this, they crave tweet and blog attention, but our tweet total wheezes to a halt at around 35.

Davenport is a veteran at coping with problems, which can dog an expedition leader every step of the way. Before the trip, a benefactor (whom Davenport can’t name) pulled out after promising him $100,000. Helly Hansen had to pull out, too; late last year, it greatly reduced the size of its sponsored-athlete program. The twin losses caused out-of-pocket boat costs to skyrocket to more than $9,000 for each passenger.

But Davenport and Hagen landed on their feet. Days before leaving for Ushuaia, they cut new deals with a Helly competitor, Spyder. Known for its ski-racing skin suits, Spyder wants to launch a big-mountain collection, and Davenport and Hagen happen to be two of ski mountaineering’s marquee names. During our time on the Australis, between viewings of violent DVDs like Pulp Fiction and The Punisher, Davenport and Hagen sat at a table, sketching new designs for Spyder. “We’ll name them after Duseberg Buttress, Demaria, and other first descents down here,” Hagen said.

The two are actively involved in the collection, and their deal is structured like the relationship between Burton and the late snowboarder Craig Kelly. The big-mountain line AK, which sponsored him, sold like crazy, earning Kelly considerable profits before his death by avalanche in 2003. Hagen and Davenport believe they can do well, too. As they look at existing product, they’re vocal about skiwear design. Hagen rips Helly for a jacket’s counterintuitive cuff closure. Don’t get him started on pockets and zippers.

ON THE SUNDAY after Thanksgiving, a few of us take a Zodiac to 65° 15′ south, 64° 16′ west, the coordinates of Vernadsky Station, a science outpost that specializes in measuring ozone depletion.

The oldest operational station on the peninsula, Vernadsky was founded by the British on Galindez Island in 1947 and handed over to Ukraine in 1996. Today it hosts five scientists, four mechanic/electricians, a doctor, a cook, and a custodian. All are male, and all seem pleased that Skye, not her boyfriend, escorts us on our visit. She is exceptionally pretty for a first mate, with long raven hair, doe eyes, and a pierced tongue. The scientists fawn, though their rough English makes for especially small small talk.

@#95;box photo=image_2 alt=image_2_alt@#95;box

Almost all of the Ukrainians sport mullets, tight jeans, and cigarette breath. They take us on a tour of Vernadsky. Rooms appear mostly spotless. The ozone-measuring device, an underwhelming assemblage of white metal tubes, sits in a dark attic. Skye enters the gym and quickly walks back out its walls sag with centerfolds of nude women. When not perving, the Ukrainians play snooker and Ping-Pong.

Vernadsky also hosts the southernmost souvenir shop on earth, selling $20 bottles of “low ozone air.” We don’t buy any. Instead we eat overcooked beef kebab and drink homemade vodka, a blend of “water, Antarctic ice, yeast, and magic!” according to a Ukrainian who’s wearing a piece of six-millimeter rope as a headband.

In the bar, the main focal point of a Vernadsky visit, I pound five vodka shots and talk with meteorologist Eugene Lomakin, who bemoans the nearby penguins. “They leave very bad smells,” he says. “Ugh! They’re very funny, but we hate them.” The penguins are currently tending to eggs, which makes them aggressive. “When I go to check meteorological equipment, they bite my calves,” he frowns.

��

As we all know, things were a little rougher around Antarctica in the old days. (See, for example, Ernest Shackleton and the Endurance, 1915 16.) Shackleton got iced in about 250 miles from here, and one of the peninsula’s most imposing peaks is named Mount Shackleton in his honor. It stands at 4,805 feet, with an abrupt, 3,000-foot ridge littered with crevasses and seracs. Sickly steep couloirs spill down from the summit, and, not surprisingly, Mount Shackleton has no recorded descent. It’s a geologic monster. Scoping it with binoculars from the Australis deck on the night of December 4, Hagen says, “If we do Shack, we’ll be really happy. We’ll go home having accomplished something as ski mountaineers.”

Shackleton is far from the shore, so we can’t approach it as a day trip. We’ll need to haul tents, stoves, and sleeping bags, and to overnight on a glacier. Says Davenport, “I’ve sold my soul to Mother Nature several times, so I hope she’s nice.”

While Workman and Simper stay on the boat, six of us set off the next morning under ominous conditions. Gray skies glare at choppy seas. As we boat to the approach, icy water splashes over the bow, soaking gloves and soft shells. Shivering, we strap crampons to our alpine-touring boots and kick our way up an unstable face, skis riding our heavy packs. When the pitch flattens, we put climbing skins on our skis and stride. We climb roped together in three-person teams, in case a crevasse opens up.

After five hours, we quit skinning and establish a base camp, stomping platforms for two Black Diamond Bombshelter expedition tents. With shovels, we dig out shelves for cooking, then fire up MSR stoves. We melt snow, brew tea, and cook freeze-dried meals that Hagen bought in Norway. (Try the Turmat Storfegryte beef stew you can thank me later.)

We wake to four inches of new snow, with crappy visibility. We make a pre-arranged 11 a.m. radio call to Workman on one of our seven Motorola Talkabouts. He confirms the worst: The forecast shows no clearing till the next morning.

Slight, sporadic patches of blue “sucker holes,” in skier parlance convince us to wait in the tents for a miracle. But at 2 p.m., we finally admit the obvious: We can’t risk Shackleton in these conditions. “There’s no room for error here,” says Binning. “You’re such a long way from help. In that respect, Antarctica is a more dangerous place to ski than anywhere else. You can’t fuck up.”

“Yeah,” says Davenport, “even in the Himalaya there are helicopters. This is the only place where rescue is not an option.”

OUR DAILY ROUTINE becomes familiar: We hand skis down from the deck to the Zodiac each morning, then bounce in ourselves. To avoid puncturing the inflatable pontoons, we stick axes, Whippets and self-arrest poles, and crampons in a plastic bucket.

On December 8, midway through a sunny afternoon, we set off for a 45-degree, diamond-shaped face spilling off the Arctowsky Peninsula. The athletes call it the Sphinx, after a similar steep in Alaska’s Chugach Range.

Though it’s softening to the point of spring snow conditions, the Sphinx should be safe to climb. Which it is. For about 20 minutes. Then the sun becomes more direct. In the invisible distance, great chunks of ice are crashing into the sea. We begin to remember that today is the austral equivalent of June 8. Small rocks begin whizzing down, released by the sun from the Sphinx’s icy grip. Sporadic at first, rocks are unleashed every minute or two. The athletes, two-thirds of the way up the 1,700-vertical-foot pitch, announce they’re skiing down now.Afterwards, on the deck of the Australis, Hagen says, “Those rocks could come down at 100 miles per hour and take your head clean off.”

“The rocks were small at the beginning,” Davenport says. “Then all of a sudden they were softball-size. They’d kill you so fast. The mountain can’t talk any more clearly. It said, ‘Get the hell off!’ “

“We should have retreated earlier,” Binning says, “but we could smell the summit.”

Three days later, we head back to the Arctowsky. This time, we start moving up a chute to skier’s left of the Sphinx, climbing with crampons and ice axes. The pitch is steeper than anything this side of vertical ice. It’s best to look up at all times, to see what’s above and where to sink the next sharp. Yet we can’t help but look to the side every now and then. That’s when you feel like a badass: when the mountain looks damn near perpendicular to the horizon. Not that you notice the horizon much, what with the unfiltered-by-ozone sun sparkling up the clear water, icebergs disintegrating into “bergie seltzer,” and breaching whales exhaling happily through their blowholes.

Shaded by its walls, the chute releases no stones. We snap photos of each other sticking to pitches that only tree frogs should adhere to.

From a distance, GVD and Simper capture panoramic shots. Through their viewfinders and binocs, they see us summit the Sphinx. They spot Surette filming a mountaintop interview with the athletes before they drop the face. With Davenport leading off, the pros etch huge, bold lines on a 52-degree slope, which Davenport calls “the coolest line of the trip.” Yet Surette, Workman, and I can hear that the snow on the Sphinx has yet to soften their turns sound like knives on Styrofoam.

We decide to ski the much narrower but not-quite-as-steep only 45 degrees ascent couloir. We know the snow is much softer. Besides, dropping the ascent means we’ll snag a first that the athletes can’t claim.

It’s our last day on skis; 36 hours later, we’ll head back across the Drake. Back on the boat, euphoric, we attempt to dent the seemingly infinite supply of Quilmes cervezas. (We brought 26 cases.) The sun refracts off ten pairs of high-tech sunglasses. “That’s 12 sunny days,” Davenport points out, “which is absolutely not normal for the Antarctic Peninsula.” It’s his understanding that the place usually enjoys only 60 clear days per year.

As the Australis knifes between bergie bits through blue water, a humpback whale flirts with us. It’s like SeaWorld minus the biologists in short shorts. The playful cetacean swims fore, aft, alongside, and underneath the boat. It fires its 35 tons in and out of the sea splashing huge, flashing its prehistoric flukes. Davenport runs to the deck to watch, saying, “It’s amazing we’ve been here 18 days and we’re still freaking out!”

GVD, the pro photographer, is the only one to really capture the diving humpback. But that doesn’t stop the rest of us, armed with our point-and-shoots, from snapping approximately 87 shots as well.

Everyone, everywhere, thinks they can shoot good photos. GVD’s territory has definitely been infringed on. But so has mine: Judging by the blogosphere, everyone thinks they can write. And on our trip, the pros ski steeps that pucker even their experienced sphincters, but still we media types think we can keep up. Everyone can do everything.

These days, adventure seems less inspirational than aspirational. One would hope that Antarctica still represents a barrier of some kind. But I know what you’re thinking: “If I had ten grand for the boat and a month to play, I could do that.” Maybe. Thing is, you haven’t. Davenport has. He traveled through seven airports, shared a balky boat toilet with nine people for a month, and rang up four possible first descents. Five if you count the iceberg.