MY COMPANIONS and I are sitting shoulder to shoulder in the snow at Mount Rainier’s Camp Muir (elevation 10,188 feet), hunched over plastic mugs containing a lukewarm paste of rehydrated vegetable soup. It is late spring, when the climbing and skiing in Washington and Oregon’s Cascade Range are reputed to be at their finest, but for the past 48 hours an alpine gale has been scouring Rainier’s upper flanks with the relentlessness of an industrial sandblaster. This is Phase One of a weeklong ski-mountaineering trip, the purpose of which is to knock off four of the most significant Cascade volcanoesÔÇöMounts Rainier, Adams, Hood, and St. HelensÔÇöin descending order of magnitude. It’s an ambitious goal, to be sure, but one we had hoped was at least marginally within our grasp.

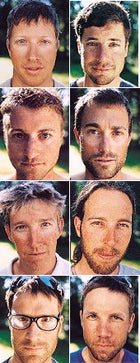

The Crew: Team Desk Jockey: from left, Casey Vandenoever, Chris Keyes, Eric Hansen, Eric Hagerman, Kevin Fedarko, Marc Peruzzi, Tim Neville, and Nick Heil, all looking a little shell-shocked on day nine after more than 42,000 vertical feet of climbing and skiing

The Crew: Team Desk Jockey: from left, Casey Vandenoever, Chris Keyes, Eric Hansen, Eric Hagerman, Kevin Fedarko, Marc Peruzzi, Tim Neville, and Nick Heil, all looking a little shell-shocked on day nine after more than 42,000 vertical feet of climbing and skiing Blisters and baggage: an up-close-and-personal view of keye’s heel on day three(left), and a partial sample of all the crap we brought along

Blisters and baggage: an up-close-and-personal view of keye’s heel on day three(left), and a partial sample of all the crap we brought along Because it’s…where? Doug Ingersoll, center, points out Rainier’s summit to Hansen, Vandenoever, and Fedarko, from left.

Because it’s…where? Doug Ingersoll, center, points out Rainier’s summit to Hansen, Vandenoever, and Fedarko, from left. An overview of three charismatic peaks we hit (and one we missed)

An overview of three charismatic peaks we hit (and one we missed) Eighteen feet and rising

Eighteen feet and rising At the moment, however, that hope is dwindling. It has been puking snow all spring, and we’ve arrived to find the Cascades mantled in a thick maritime snowpack that’s unstable at best, downright lethal at worst. Fourteen days ago, three climbers on Rainier were seriously injured by falling ice. And later that same morning, a 29-year-old woman slipped and fell 2,500 feet to her death on Hood. Further complicating things is the creeping realization that we lack both the skills and the knowledge required to climb the glaciers and technical terrain that separate our current camp from Rainier’s summit, 4,222 feet aboveÔÇöa deficiency that’s being hammered home by a voluble authority figure, clad in a red one-piece ski suit, whom we’ve begun referring to as…The Doug.

Doug Ingersoll, 38, boasts the kind of perma-tan you’d expect from a backcountry ski icon or a professional mountain guide (both of which, in fact, he is). Since meeting up with us two days ago at the base of Rainier, Ingersoll has been burnishing his role as alpha male by barraging us with anecdotes about his skiing virility (in 1998 he participated in the first ski descent of a 4,000-foot pitch on Rainier called the Mowich Face) and his sexual dexterity (he once won a contest at a party by corkscrewing his “unit” before a panel of female judges, a stunt he dubbed “twist-a-peenie”). Right now, though, Ingersoll has cast off his breezy schtick and adopted the droop-jowled gravity of an Arkansas hanging judge.

“Look, mountaineering is all about having your shit dialed,” he intones, standing before us on the Muir Snowfield. “If you don’t have your shit dialed up here, you’re putting yourself really low on the food chain. And at the moment…” Here, Ingersoll pauses and cocks one of his eyebrows theatrically. “To be honest, you guys are pretty much at the bottom of the fuckin’ food chain.”

IT’S BAD ENOUGH to hear this kind of thing from a guide whom you’re paying to keep you alive in the mountains, but Ingersoll’s connection to our venture is far more tenuous: He basically invited himself along for the fun of it, an offer we accepted, thinking his skills would help to offset our weaknesses. Nonetheless, his assessment is painfully accurate. Ever since we left the parking lot, nearly 5,000 vertical feet below, inexperience has been swirling around us like spindrift.

At the trailhead we discovered that Michael Darter, our freelance photographer, forgot his climbing skins, a mistake that forced him to boot-pack the entire route to Muir. Less than two hours into the climb, three of us who hadn’t bothered to break in our ski-mountaineering boots with fully loaded packs (see “Screw-ups,” page 100) were desperately patching blisters with moleskin. Our collective lack of preparedness became most clear at Camp Muir when Ingersoll informally quizzed us on climbing knots. A few of us were able to produce a well-wrought butterfly, a standard knot used to tie in to the middle of a rope, but we all failed horribly when it came to equally important (and simple) knots like clove hitches and bowlines. If there was a point at which we felt that Ingersoll might be an overbearing egotist threatening to take over our trip, it was also starkly apparent why we needed him. He could tie a bowline with one hand; I couldn’t tie one with two.

As I sat listening to The Doug and staring into my glutinous, rapidly chilling dinner, I couldn’t help but think that what had started out as a classic ski-mountaineering trip was spiraling into disaster. The group had become laconic, even sullenÔÇögone were the wisecracks and ribbing that were standard fare during the months of planning and training that got us here. Earlier I overheard two of my companions speaking in hushed tones about bailing out and going kayaking down in Oregon. We’re doomed, I thought. Even if we summit Rainier, the fraternal fabric we’ve knit together has shredded. And, because both the trip itself and Ingersoll’s presence on it were my idea, it’s entirely my fault.

AFTER spending our second evening on Rainier listening to The Doug’s alpine homily on the importance of dialing one’s shit, we pushed back our summit bid by a full day and submitted ourselves to a crash “glacier clinic” in which Ingersoll provided crack instruction on snow anchors, crevasse rescue, and emergency rope-team protocol. Then we turned in for a few hours of rest, serenading one another to sleep with some remarkably bold concertos of tent flatulence, courtesy of the rehydrated vegetable soup.

At midnight we arose, roped up into two five-man teams, and wound our way through the frigid dark along the base of Gibraltar Rock, ten headlamps bobbing beneath hulking black cliffs. Our summit route, the Ingraham Direct, would take us right through the middle of the Ingraham Glacier. We stumbled over the exposed volcanic rock, crampons flashing sparks, and plowed our way to the base of the Ingraham Headwall, whose silhouette was limned by a dense scrim of stars.

Ingersoll, at the head of the lead rope team, started boldly up the steep pitch, which required us to use our front points for purchase, then led us over the lip into a labyrinth of towering ice blocksÔÇöthe intestines of the glacier. Moving through the ice maze in the dark was precarious businessÔÇöcorridors would close out; snowbridges were fragile. At one point, Peruzzi stepped through a crust of snow covering a crevasse and plunged in up to his waist, legs dangling in space. “You should be more careful!” scolded Ingersoll.

I had summited Rainier for the first time in 1998, and I hadn’t forgotten what the last 1,000 feet feels like. It hurtsÔÇöan endless, bitter predawn trudge up a 30-degree ice ramp, during which you’re pummeled by wind, exhausted, dehydrated, and reeling from the altitude. Five steps. Rest. Five more steps. Rest. Repeat ad nauseam. And then, almost suddenly, you’re there, hitched up along the boulders that border Rainier’s summit caldera. We arrived at just after 6 a.m. and stayed only long enough for Keyes and Hansen to trundle over to the opposite end of the caldera so they could perch on Rainier’s highest point, roughly 200 feet above where the rest of us were slumped in exhaustion. For the rest of the trip they swaggeringly billed themselves as the only two “official summiters.”

During our descent we stopped for a rest at Ingraham Flats, lounging in the broiling late-morning sun to snack on cheese. Back at Muir, as we broke camp and strapped on our skis and boards to head down the final 5,000 feetÔÇöa brutal task, given our advanced state of fatigueÔÇöwe realized we were completely out of water and, thanks to our extended stay at Muir, had no fuel to melt snow. We were pondering this problem when a hiker materialized holding two plastic gallon jugs of water. “I haul these up because the extra weight is good training,” he said. “I was just going to pour them out. You guys look like you might want ’em.”

Someone (I’m pretty sure it was me) let out a noise somewhere between a laugh and a sob.

WHILE WE LOADED our rigs in the parking lot at the base of Rainier, Ingersoll urged us to follow him north to Mount Baker, where he generously offered to guide us up the mountain and show us some of the finest glacier skiing in the Northwest. At some point during our ski descent of the Muir Snowfield, however, an odd feeling had overtaken each of us. Partly it owed to the euphoria we felt at the nearly flawless 14-hour round-trip we’d just completed with Doug’s help, but I think it had even more to do with a renewed collective determination, fueled by what we had both gained and given up on Rainier, to reconnect with our original plan. We’d lost two days, so we’d have to cut out Mount Hood, the least enticing of our Ring of Fire objectives (its most direct summit route entails hiking up through the Timberline ski resort). But if we busted a move, we could still bag two of the three remaining peaks on our own. We shook hands with Ingersoll and thanked him sincerely for all he had done. And then we sped south for Adams.

AT 12,307FEET, Mount Adams is a lesser giant than Rainier, but still formidableÔÇöan elegant massif with fir-studded flanks and snow-draped shoulders that is believed by many to be the loveliest peak in the entire Pacific Northwest. Partly owing to our time constraints, we planned to camp at the Cold Springs trailhead and summit in a single, punishing 6,700-foot push up the South RidgeÔÇöa route that doesn’t require ropes or protective gear other than ice axes and crampons. If we got lucky with the weather, we’d be able to ski straight off the top and carve turns all the way back to camp. Summiting Rainier may have been viscerally intense, but as far as we were concerned it couldn’t hold a candle to the rapture of linking turns through the virgin snow on Adams.

We awoke well before dawn and launched a rhythmic attack on the series of wide, steep snowfields along the mountain’s southern rib, spurred by the bracing realization that we were now on our own. Nine hours later, we crested the summit of our second peak and, in one of those acts of grace that nature sometimes affords, were greeted by a vista that was striking even by Cascades standards: There, winking back at us 80 miles to the north, its blue glaciers shimmering in the crystalline air, was Rainier. To the south, just across the Columbia River Gorge, rose the sharp spire of Hood. And 50 miles to the west, the razed dome of St. Helens. We gazed in silence for several minutes while waiting for Hagerman, who had stalled out and almost given up due to fatigue. When he finally arrived, he annihilated the delicate and beautiful moment by seizing his ski pole and walloping the summit with enough fury to create a small cloud of snow crystals. “I beat you, you son of a bitch! Take that and that and that!”

We cruised off the top on our skis and boards, hacking through 400 feet of sastrugi ice burrs until we reached the 700-foot, 40-degree ramp that leads from Adams’s false summit down to a broad plateau called the Lunch Counter. It was midafternoon, the snow on the ramp soft and consistent so that our edges set easily, almost automatically, and then sliced into buttery arcs. Several of us had skied big mountains before, but none had ever experienced anything like thisÔÇöthe brilliant summer afternoon, the skis and boards hissing beneath us, the marvelous sensation of dropping into that elusive flow state in which body and mind move to the cadence of a synchronous, elemental inner vibe. “Well,” announced Keyes, as we pulled into camp around 5 p.m., capping a 12-hour marathon, “I’d say that was pretty much the best day I’ve ever spent in the mountains.”

IT WAS exhilarating how the momentum of skiing multiple peaks seemed to build rather than diminish: The next morning we broke camp, hiked out, loaded our trucks, and headed straight for Mount St. Helens, which offers a long (4,500 vertical feet) nontechnical walk-up and skiing every bit as delicious as that on Adams. We arrived feeling that we were firing on all cylinders and exhibiting an almost Ingersollian ├ęlanÔÇöa mind-set that was dealt a rude blow when we caught up with a troop of ten-year-old Girl Scouts merrily skipping up the route we’d chosen. We scampered up to the rim in a brisk three and a half hours, completing our revised goal: three peaks in a week. Not too shabby. A thick wash of fog was rolling in below us and appeared to be rising, so we didn’t dally. We clicked into our gear and boogied down the ash-dusted snow. As we whisked past the Girl Scouts, who were firing up the cinder ridge at Marine Corps pace, somebody yelled to ask if they’d already done Adams or Rainier. Fortunately for us all, perhaps, their reply was lost in the fog.

WE CASHED IN our last night on Bainbridge Island, northeast of Seattle, where Eric Hansen’s family has a beach house. As we drove the three hours to the place, I realized that this, even more than the climbing and skiing, would be the moment I relish mostÔÇöthe seam between the denouement of an adventure and the cold shock of reentry to your life, when your body still vibrates from the physical challenges in a way that makes you feel renewed, expanded. That evening, we plucked and shucked oysters from the bay next to the cottage. We grilled salmon steaks and cooked a huge pot of pasta. We uncorked bottles of wine. We drank three cases of Rainier Beer. And soon the ideas about other possible trips were tumbling out: something in Patagonia, perhaps, or Alaska’s Brooks Range, or maybe a wilderness canoe trip through the Northwest Territories. As the conversation eddied and rolled, I ducked out and walked down to the dock, where I stared up at the stars and pondered the trip’s balance sheet of risks, frustrations, and rewards. Was it a success? Had it been worth the effort? I looked toward the house and got my answer. Through the kitchen window, I could see my friends sitting at the dining table, laughing and lifting their glasses in the air, and I realized what they were doing. They were offering a toast to our next self-guided adventure.

I walked back to the cottage to find out what it would be.

1 Mount Rainier

ELEVATION: 14,410 feet

Time on the Mountain: Four days (it took 14 hours to climb from Camp Muir to the summit and then descend to the Paradise parking lot).

Summit route: From Camp Muir, we took the Ingraham Direct (an alternative to the standard route up Disappointment Cleaver).

2 Mount Adams

ELEVATION: 12,307 feet

Time on the Mountain: 24 hours

Summit Route: The South Rib from the Cold Springs trailhead, where we camped

3 Mount St. Helens

ELEVATION: 8,366 feet

Time on the Mountain: 18 hours

Summit Route: Monitor Ridge from our camp at Climbers’ Bivouac.

4 Mount Hood

ELEVATION: 11,235 feet

Next time

The Lowdown The Ring of Fire

LENGTH OF TRIP: Nine days

WHEN TO GO: Late May through early July

REQUIRED FITNESS LEVEL: High

MINIMUM PREPARATION TIME: Three months

REQUIRED SKILLS: Big-mountain skiing or snowboarding, backpacking, winter camping, nontechnical grades II and III climbing on snow and ice

* The Objective

To climb and skifour of the most significant peaks in the Cascades during the course of a week: Mount Rainier (14,410 feet), Mount Adams (12,307 feet), Mount Hood (11,235 feet), and Mount St. Helens (8,366 feet). In our case, we failed to knock off Hood; but the remaining three peaks offer glacier travel, substantial nontechnical climbing, and 17,000 vertical feet of glisse.

* Skill Requirements (Mountaineering)

All routes to Rainier’s summit require roped team travel. See page 104 for a checklist of requisite skills and a directory of schools where you can acquire and polish them.

* Skill Requirements (Skiing/Snowboarding)

Corn snow is hero snow: Softened by spring’s warm days, it gives an intermediate skier the confidence to descend expert terrain. But cold fronts and wind can instantly turn corn back to ice, or worse, either brittle sastrugi (think ankle-deep broken glass) or sun cups (ice with more dimples than a Palm Beach County ballot). Attempt this trip only if you’re comfortable skiing or boarding all runs in all conditions at any major ski area.

* Fitness Requirements

This is a rigorous outing. Rainier is a sea-level fourteener, so, unlike in Colorado, where you might ascend only 5,000 feet from trailhead to summit, here you’ll climb a full 9,000. Pulling off all four volcanoesÔÇöor even just threeÔÇöin a weeklong push demands a serious approach to fitness (and a fair amount of luck). See “Powering Up” on page 104 for specific training information.

* Gear Requirements

This trip is extremely gear intensive. For a comprehensive inventory of the mountaineering and skiing equipment, see “Walking Is for Hikers,” page 107, or www.outsideonline.com.

* Is It for You?

This is an ambitious yet classic North American ski-mountaineering trip. It will bust your ass and empty your wallet; but unlike a commerically guided trip (of which, in fact, there are none for the four-peak plan outlined here), you’ll return with the gear, skills, and partnerships that will enable you to do it again.

The Damage

Ground Transportation

$2,130.59

Rental of two SUVs, gas, parking, tolls

Airfare

$1,920.00

Eight round-trip tickets, Santa Fe to Seattle

Food

$1,017.04

Pasta, ground meat, fresh vegetables, freeze-dried meals, cereal, energy bars, powdered drink mix, Gu, and three cases of Rainier Beer

Permits

$275.00

Climbing permits for Rainier, Adams, and St. Helens

Specialized Gear

$2,172.17

Avalanche transceivers, rope, perlon, carabiners, climbing harnesses, helmets

Total Cost Per Person:

$939.35

Note: This figure does not include ski orsnowboard setups, clothing, packs, or tents.

WHEN THE PERSON behind the desk at Mount Rainier’s Paradise Ranger Station asks how many “blue bags” you want to pack up the mountain with you, take our advice and err on the side of plenty. The self-sealing, heavy-duty plastic sacks are the key to keeping Rainier’s most popular routes relatively free of human waste. (If you think this isn’t a big deal, consider the following: Last year, the portable toilets at Rainier’s two high camps, Muir and Schurman, accumulated 15,600 pounds of excrementÔÇöevery ounce of which had to be helicoptered off the mountain.) Blue bagging, however, is only part of the commitment you should make to minimum-impact ski mountaineering. Here are a few other points to keep in mind:

* Eat what you cook; pack out what you don’t. It’s a no-brainer, but we’ve gotta say it: Haul out all litter, even trash that’s not yours. And remember that burying your garbage in the snow or tossing it into a crevasse is not an acceptable means of disposal.

* When camping on heavily trafficked routes on popular peaks such as Rainier or McKinley, be thoughtful and leave your snow structures standing for the next party. In more remote areas, knock them down to hide your traces.

* On tight bivouacs where snow is scant, avoid the few pristine patches of powder when it comes time to pee. Otherwise, you contaminate the water supply for you and everyone else.

Resources

Twenty years ago, ski-mountaineering guidebooks were largely nonexistent. Now, everyone’s either an author or a reader. Below, a list of our favorites.

Location-Specific Guidebooks:

NORTH AMERICA

Wild Snow: 54 Classic Ski and Snowboard Descents of North America, by Louis Dawson.

THE ROCKIES

The Chuting Gallery, by Andrew McLean

Teton Skiing: A History and Guide to the Teton Range, Wyoming, by Thomas Turiano

*Wasatch Tours, by David Hanscom and Alexis Kelner

Dawson’s Guide to Colorado’s Fourteeners, by Louis Dawson

THE WEST COAST

*Backcountry Skiing Washington’s Cascades, by Rainier Burgdorfer

Exploring the Coast Mountains on Skis, by John Baldwin

Cascade Alpine Guide: Volumes I, II, and III, by Fred Beckey

Backcountry Skiing California’s High Sierra, by John Moynier

NEW ENGLAND

Backcountry Skiing ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°s: Classic Ski and Snowboard Tours in Maine and New Hampshire, by David Goodman

*Classic Backcountry Skiing: A Guide to the Best Ski Tours in New England, by David Goodman

*Northern Adirondack Ski Tours of New York, by Tony Goodwin

General-Reference Guidebooks:

Allen & Mike’s Really Cool Backcountry Ski Book: Traveling and Camping Skills for a Winter Environment, by Allen O’Bannon and Mike Clelland

Backcountry Skier: Your Complete Guide to Ski Touring, by Jean Vives

Backcountry Avalanche Awareness, by Bruce Jamieson

Free-Heel Skiing, by Paul Parker

Rock & Ice Gear, Equipment for the Vertical World, by Clyde Soles

* Out of print