ONE APRÈS-SKI GOLDEN HOUR LAST MARCH, Daron Rahlves, three-time Olympian and retired U.S. Ski Team star, was standing in the middle of Squaw Valley’s Le Chamois bar in his underwear. Another fallen sports hero? It’s as good a guess as any. But Rahlves, it should be noted, was sober, and he had stripped only as a favor for a camera crew from ABC Sports, which needed footage to promote his latest high-speed, adrenaline-fueled pursuit, skiercross. An X Games favorite heavily influenced by motocross, skiercross sends four to six skiers at a time down a swerving, jump-studded, wildly ramped Alice’s rabbit hole of a course. Elbows fly, and if you cut off your enemy and send him careering off the course—hey, bonus.

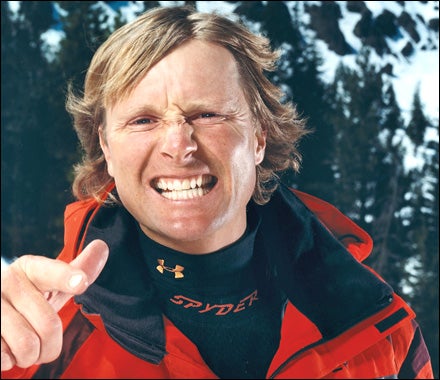

daron-rahlves

Rahlves between careers at Sugar Bowl

Rahlves between careers at Sugar Bowldaron-rahlves

Rahlves working his big-mountain mojo in the Sierra Nevada

Rahlves working his big-mountain mojo in the Sierra NevadaThis was not what Rahlves expected when he retired from World Cup racing following the 2006 season. With 28 podium finishes, 12 wins, three world championship medals, and a reputation as America’s best downhiller, Rahlves, 34, planned to leave racing behind and try big-mountain freeskiing—those helicopter adventures to the steeps of Alaska that supply each year’s new crop of ski porn. “It’s nice not dealing so much with edges,” he explains of the switch from racecourses to powder. “Nice not having to try to hang on to the ice all the time.”

It’s a transition no major racer has nailed, though. Sure, other U.S. Ski Team members have morphed into great freeskiers. Big-mountain heroes Jeremy Nobis and Wendy Fisher each raced at one time for the Stars and Stripes. But they all found their new mojo early. None enjoyed Rahlves’s success or longevity on the World Cup circuit.

But a funny thing happened on the way to the chopper: The International Olympic Committee, to everyone’s surprise, added skiercross to the 2010 Winter Games as a full medal sport. Then came the 2007 launch of the Honda Ski Tour—a well-funded, heavily promoted four-event series billed as “the Loudest Show on Snow.” The Ski Tour combines skiercross with terrain-park competitions, surrounds it all with fashion shows and rock concerts, and multi-platforms the bejesus out of its imagery. Rahlves hasn’t abandoned his big-mountain plans. Now, though, between waiting for weather windows in Alaska, he’s found another way to stay in the spotlight and on sponsors’ payrolls. “Skiing doesn’t pay nearly as well as during my World Cup career,” says Rahlves. “But the only sponsors I lost after leaving the U.S. Ski Team are 24 Hour Fitness and Oroweat bread. My Austrian sponsors, Red Bull and Atomic Skis, especially love the new exposure I give them.”

This explains his lack of pants. Squaw Valley was hosting the final stop of the 2007 Ski Tour, and Rahlves was enduring a made-for-TV costume change. After first modeling his old skintight World Cup downhill wear, he stripped and put on skiercross apparel: same helmet and goggles but with softer boots, back and knee pads, baggy black pants, and a lime-green miracle-fabric windbreaker with RAHLVES embroidered on the back. The purpose of all this haberdashery, the racer deadpans, was “showing schoolkids how to get dressed.”

The purpose might also have been to lift his Q rating higher than ever. While Rahlves hopes to shoot this winter with Matchstick Productions—the biggest seller of freeskiing DVDs—the Ski Tour, which has since acquired the Jeep King of the Mountain tour, will expand in 2008 under a new name, 48Straight, and will try to ride the buildup toward 2010, when America will renew its quadrennial love for winter sports, and skiers will become media “gets.” If Rahlves can polish his ‘cross skills a bit more—that is, if he can stop crashing in the finals—his could be the face you see on late-night TV. The reinvented stud whose post-skiing career … is a skiing career.

“MY HIP IS CLICKING,” Rahlves observes on a chairlift at Sugar Bowl, a resort near Squaw Valley. “It shouldn’t be.”

It’s Thursday, three days before the Ski Tour’s ‘cross finals at Squaw, and Rahlves is testing his pelvis. It hasn’t felt right since February, when, at the third stop on the Ski Tour, in Aspen/Snowmass, he caught an edge during a training run and shot 20 feet in the air before splashing down so hard he left three-inch divots in the hardpack. He looks solid enough to me, though, slashing his Atomic giant-slalom boards against a frozen steep named Rahlves’ Run. Huge chunks of terrain get swallowed with each turn. If he’s down to one hip, that hip is excelling. Rahlves appears, as only racers can, to accelerate out of his turns. Nominally, those are braking moves. Yet I can’t keep up with him, despite beelining straight down on a healthy hip. Must be a wax thing.

��

But all of this—the athletic grace, the fun-at-any-cost mind-set, the multi-pronged unretirement—is perfectly in character for Rahlves. If this guy wants to star in ski films and a new Olympic discipline, expect to see him on DVDs every winter and in sit-downs with Bob Costas in 2010.

The son of a champion water-skier, Rahlves was always primed for athletic success. He and his younger sister were raised active and outdoorsy in the Bay Area and on the California side of Lake Tahoe. He recently took up skateboarding and already excels at snowboarding, mountain biking, wakeboarding, surfing, jet skiing, and motocross. Excels on a world-class level. He claimed the 1993 World Jet Ski Championship in the expert division, completed the Baja 1000 motocross relay in 2006, and won his class at the prestigious Glen Helen Outdoor National motocross race, in September. Though he spends most of his days at his family’s longtime Truckee compound—with his wife, Michelle, and their six-month-old twins, Dreyson (a boy) and Miley (a girl)—Rahlves just bought a second home in Southern California to be closer to moto-friendly desert and good surf.

“I was there in January and February surfing—the first time in my life I wasn’t in a wintry place in those months!” Rahlves beams.

He says the world jet-ski championship in ’93 marked a turning point: whether to train for the highest echelon of that sport or for ski racing. He chose the latter “because it was more of a challenge” and was racing on the World Cup circuit a year later. Good choice.

At five foot nine and 175 pounds, Rahlves gave up at least 20 pounds to Bode Miller, Tommy Moe, and the other hosses he raced against, and he lacks the Buick-size trunk found on gold medalists like Picabo Street and Hermann Maier. “A bigger guy can go faster on a straightaway than a small guy like me,” Rahlves tells me at Sugar Bowl. “So I learned to really stick my turns in just the right place and at just the right time.”

Among his 12 World Cup wins was a victory in the 2003 Hahnenkamm, the most hallowed downhill in the world. The slope, already steeper than Stephen King’s forehead, is fiendishly watered down to make it icier. Rahlves is the only American to have won it in the World Cup era, and the performance made him a legend in Europe, where Hahnenkamm wins mean more than Olympic medals.

Unlike most of his contemporaries, Rahlves had a tendency to disappear into back bowls whenever races were canceled because of excess snow. “Eighty percent of World Cup racers wouldn’t touch powder skis or hit jumps,” he marvels. “They said powder would ruin the feeling of a course!” Raised on the Pacific-fattened dumps of Tahoe—Bode Miller grew up on the ice sheets of the Northeast—Rahlves always craved the stuff.

In the past few winters, though, weather cancellations started happening more because of drought or unseasonable murk. “I had gotten spoiled,” Rahlves says of his last year on the World Cup. “If it wasn’t perfect weather, if the conditions sucked, I’d lose interest. All the years of traveling, training, and committing to one sport began to wear on me. It was the right time to walk away.”

Rahlves made his competitive skiercross debut at the X Games last January, easily winning the individual qualifying run and every heat through the semifinals. But in the finals he got squeezed off his line and knocked off balance. His left ski ripped away from his boot, his arms flailed, and he landed on his can as his opponents sped away. “Shit happens so much quicker in ‘cross,” he says. “You’re not skiing the run; you’re skiing the guy in front of you.”

He also biffed at the first Ski Tour ‘cross, in Sun Valley in January, and then again at Breckenridge in February. Then there was the February crash at Snowmass that injured his right hip. Despite all this, he headed into the finale at Squaw in seventh place in the series standings.

“Daron gets impatient sometimes,” says Casey Puckett, another American World Cup and Olympic veteran who’s become the world’s top skiercross racer. “You want to pick your places to pass. Most of the time you see crashes is when a guy tries to make a pass where it’s impossible.”

For his part, Rahlves admits he still has a lot to learn. “Ski racing, it’s just me versus the mountain,” he says. “Here, it’s me versus the mountain plus three other guys.”

IN THE END, RAHLVES’S HIP keeps him out of the race at Squaw. “Pro athletes need to know the right thing to do with their bodies,” he tells me as we watch the race at the finish line. “You get to know anatomy through being injured.” A few feet away, Puckett is prone on the snow, grimacing at a torn medial collateral ligament suffered in the finals.

An hour later, we take off in Rahlves’s truck, a big black Chevy Duramax with a leather interior and a sticker on the back windshield that shows Rahlves cartooned as Captain America. He drives like he skis—fast and true—and we quickly cover the dozen miles between Squaw and his five-acre spread northeast of Truckee.

Rahlves doesn’t just have a garage—he has seven. The Chevy occupies one. The others bulge with toys and trophies—a photo of his dad making a U.S.-record water-ski jump of 158 feet in 1964; the plaque from his first World Cup victory, in Kvitfjell, Norway, in 2000; the top-end snowmobile that Red Bull gave him. Three snowboards hang on the walls, along with 22 pairs of skis, including decade-old race skis, new Atomic prototypes, fat planks for Alaskan powder, and giant-slalom boards for skiercross. “I need all seven of these garages,” he says. “I couldn’t move if I wanted to.”

Three weeks later, Rahlves goes to Alaska and bags a freeskiing DVD segment in Rage Films’ Enjoy, which is out now. “It was the best heli-skiing I’ve ever had,” he tells me when we catch up in October. “Well, it was a little unstable, a little sketchy. But that makes for good filming, because a lot of snow was moving down around me as I skied my lines.”

Matchstick owner Murray Wais hopes to shoot with Rahlves this season but says the difficulty is finding time. “Freeskiing’s in Daron’s blood,” he says. “He just hasn’t had the time or opportunity to change and commit to it.”

Which brings up another new hitch for Rahlves: teamwork. Shooting video segments requires that he coordinate his performances with the ski guides, a cameraman on the ground, another in a helicopter, the pilot, and, sometimes, other skiers. “It may be selfish, but I’m not much of a supporter,” he declares. “I couldn’t fully feel the joy if I was on a basketball team and my teammate sunk the winning basket.”

That might be why Rahlves says most of his energy will go toward skiercross this winter. “I just built a start mount at my house,” he says. “As soon as it snows, I’ll have my own practice area. Last year, the start was the worst part for me. I feel I can out-ski everyone else, but I crashed at every event last year because I wasn’t out front. I’ll try to get that dialed up.”

The U.S. Ski Team, meanwhile, has just appointed a new skiercross coach, a former racer named Tyler Shepherd, in preparation for the Olympics. Rahlves knows Shepherd well and likes him but says he’s still not sure about 2010. “A lot has to do with qualifying,” he explains. “I’d like to see it done like U.S. snowboarding does—with a series of American grand prix races. If it requires lots of European World Cups, over several months, I’m a longshot to try.”

There’s just too much keeping him in America these days. He’s getting involved with his family’s commercial real estate business; trying to nurture young skiers for the next wave of U.S. World Cup stars; working with Atomic on new ski prototypes; and wining and dining with sponsor VIPs—including a group of European bankers who are flying to Aspen in February just for the chance to ski with him.

Rahlves also got pulled into a committee attempting to bring the Winter Olympics to Reno–Tahoe for 2018. By then, he’ll be 44 and no longer competing. Unless, you know, something happens and…