IF THERE'S ANYTHING that high-altitude skiers agree on, it's that skiing in or near the so-called Death Zone is rarely, if ever, anything but awful. The snow, when it's not Coke-bottle ice, stinks; the higher you go, the worse it gets. The thin air cottons your mind, deadens your legs, and makes each turn a brutal chore in a place where a sloppy one can be fatal. The Swedish ski mountaineer Fredrik Ericsson—who, in an attempt at a first descent on K2 last year, watched his partner, Michele Fait, fall to his death—has said that making four or five turns at that altitude is as hard on the legs and lungs as skiing a continuous pitch of 1,000 vertical meters in the Alps. That's if you're fortunate enough actually to ski; Himalayan expeditions, expensive and time-consuming on a good day, are as likely to end in storm-siege, retreat, or worse as they are in anything resembling success. It can take a month or more to bag a single run.

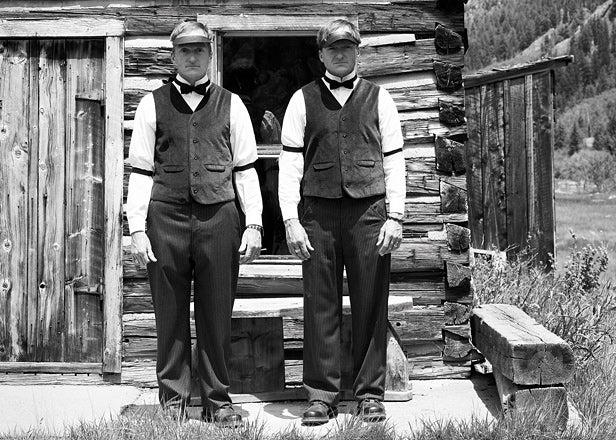

Steve and Mike Marolt

Steve and Mike, Montezuma Basin, Aspen, Colorado.

Steve and Mike, Montezuma Basin, Aspen, Colorado.Steve and Mike Marolt

Steve on Everest’s North Ridge, May 2007

Steve on Everest’s North Ridge, May 2007Which may be why so few people do it. High-altitude skiing is an eccentric and thinly populated outpost in the extreme-skiing/ski-mountaineering galaxy. It has a herky-jerk history and a lineage of larks. To most people, the idea of skiing down Everest, for example, still evokes the 1970 footage of Yuichiro Miura, the so-called Man Who Skied Down Everest, hurtling over the ice on his ass, skis spinning in the air, parachute trailing uselessly behind. Since then, others have had cleaner runs. Hans Kammerlander, Reinhold Messner's old climbing partner and the man whom many consider to be the most accomplished Himalayan skier of them all, skied off Everest's summit via the Northeast Ridge in 1996, after a high-speed ascent without the use of supplemental oxygen or Sherpas. But he had to downclimb some of the way, due to a lack of snow, and so his achievement, towering as it was, earned an asterisk. In 2000, a Slovenian named Davo Karnicar skied from the summit (which he reached using oxygen and Sherpas) down to Base Camp by way of the standard Southeast Ridge climbing route—passing, along the way, a corpse that had been lying there for four years. Over the past few decades, there have been dozens of successful descents of the 14 Himalayan peaks over 8,000 meters, for the most part by Europeans. Still, when you consider the thousands of climbers who've summited those peaks in that time, it's surprising how few of them chose to go down even part of the way on skis.

So why is it that Mike and Steve Marolt, middle-aged certified public accountants and identical twins, spend nearly every minute that they aren't preparing tax returns lugging skis toward the Death Zone or training to get back up there? The Marolts, 45, live in Aspen and are North America's most dogged and single-minded practitioners of high-altitude skiing. They are fourth-generation Aspenites from a distinguished ski-racing family. They are also, strictly speaking, weekend warriors. The term “adventure athlete,” so widely applied these days to those who make some kind of a living or name doing bold, marketable stuff out of doors, does not suit them. They are just strong skiers who happen to have devoted most of their free time, over the past two decades, to skiing at high altitude. Not least among their achievements is the curious fact that they actually enjoy the skiing up there.

Ten years ago, they became the first Americans (or, as Mike Marolt sometimes says, the first skiers from the Western Hemisphere) to ski from above 8,000 meters. The awkward wording of the claim requires explanation. The mountain was Tibet's 26,289-foot Shishapangma, the 14th-highest peak in the world. It was the Marolts' first trip to the Himalayas with skis. In October 1999, seven months before the Marolts went, an expedition of elite American alpinists had gone to Shishapangma to ski a new route down the southwest face. During the ascent, a gigantic avalanche tumbled down from a glacier and killed two of them: Alex Lowe, one of the world's top mountaineers, and Dave Bridges, a cameraman from Aspen. The attempt was abandoned.

In April 2000, the Marolts, not nearly as experienced as Lowe and his mates, went to Tibet to climb and ski the more traditional route, to and from the Central Summit, which is about 50 feet lower and much more accessible than the Main Summit. An Austrian named Oswald Gassler had been the first to ski from it, in 1985, and since then a few others had done so, but no Americans.

The Marolts had been told it was an easy eight-thousander. They were accompanied by a photographer and a childhood friend with whom they'd been going on ski expeditions for more than ten years. They were alone on the mountain. On their way up, as they acclimatized with some mid-mountain skiing, a blizzard granted them the rare gift of a powder day. Another storm socked them in 14 days later, during their summit push. On several occasions near the top, Mike considered ditching his skis, but Steve's withering look, and the fraternal imperative, persuaded him to continue on. In a total whiteout, they reached what they judged (by their altimeters) to be the peak. The summit photograph, of Steve in a fog, doesn't tell you much. It could be Snowmass or Scotland. They clicked in and skied down a moderate slope, through ice and breakable crust, to advance base camp. It was the most difficult skiing they'd ever experienced. “Easy eight-thousander, my ass,” Mike muttered to his brother.

The media's declaration, upon their return, that they were the first Americans to ski an 8,000-meter peak, ruffled some feathers, especially in light of the tragedy the year before. To their detractors, the Central Summit was one asterisk, as was the slim evidence of their having reached it. Later that year, Laura Bakos Ellison, a woman from Telluride, Colorado, climbed 26,906-foot Cho Oyu, the sixth-tallest mountain in the world, in her alpine ski boots and skied back down. She became, in the eyes of many, the first North American, male or female, to ski off an 8,000-meter peak. The Marolts again pointed out that they were the first to ski from above 8,000 meters. They've skied from above 8,000 once since, on Cho Oyu. They've twice skied on Everest's North Ridge, from 25,000 feet. (The summit is at 29,035 feet.) All told, they have six ski descents from above 7,000 meters, apparently more than anyone else in the world. (There is no ski-mountaineering governing body—official or otherwise.) They do it without supplemental oxygen, and they carry their own gear.

“People who haven't been up there and done this have no concept,” Mike says. “It's the hardest thing you'll ever do.”

Since you can't see thin air on film, the only visual hint I've had of the difficulty—and of the Marolts' unique ability to have fun regardless—is in some footage of Steve on Everest. A climber in a down suit, ascending via fixed rope and hidden behind his oxygen mask, stops and turns his head to observe Steve skiing past in a baseball cap. From the climber's bewildered body language, you get the sense that he might as well have just seen a flying turtle.

“WE'RE NOT EMBRACED by the climbing community at all,” Mike told me one night. “Maybe because we've always gotten along with our parents.”

“Maybe because we don't smoke dope,” Steve said.

We were sitting in Mike's living room in Aspen, dining on steak and drinking Stranahan's Colorado Whiskey. Bedtime was imminent; we were looking at a pre-dawn alpine start the next morning. The plan was to hike and ski Castle Peak, a fourteener in the Elk Range—for the Marolts, a training run; for me, an occasion for a restless night.

“All those guys are jerks,” Steve went on, referring to an unnamed chorus of doubters and gripers. “In mountaineering, the only way you can excel is to break other people down.”

“There's no point system,” Mike said, “so the only way to feel good about yourself is to bust on someone else's accomplishments.”

“We don't care what they think,” Steve said. “We don't need the money. We have jobs.”

Mike: “Have you ever referred to yourself as a climber?”

Steve: “I can't stand the notion.”

Mike: “I've never referred to myself as a climber.”

“You know what makes me crazier than anything?” Steve said. “Prayer flags.” Buddhism, he says, is all about letting go of ego. “And yet everyone over here puts them up to show how cool they are because they went to the Himalayas. That's all ego.”

The two are identical, yet it isn't hard to tell them apart. Mike is a little walleyed. Steve wears glasses. Mike is earnest and effusive. Steve is more acerbic and wry. I observed, rather quickly, that, as I put it to Mike, “Steve doesn't suffer fools, does he?” Mike took great delight in the phrase. Mike suffers them quite well; he's the one who chronicles, publicizes, and raises money for their trips and who put me up, and put up with me, during my visit in May. Mike is deferential and solicitous toward Steve in their daily dealings. Steve is the expedition leader. Mike was in charge of their first Asian adventure—a 1997 climbing trip to 26,400-foot Broad Peak, the world's 12th-highest, on the Pakistan–China border—but it was a mess. Steve is slightly stronger and faster. “He's a beast above 20,000 feet,” Mike says. Their mother says, “Steve is the uptight one.”

“Crabby, grouchy, curmudgeonly—that's what people tell me,” Steve says. “What do you expect after you've been carrying your brother on your shoulders for 45 years?” They're both very fit and very square. They go to church together on Sunday mornings.

The brothers live across the street from each other, in a development at the northern edge of town, near Woody Creek. “This is where the common folk live,” Mike told me as we drove up to his place. He lives with his wife, Shelly (a painter originally from New York City), and their two young daughters (whom they adopted from China) in a red ranch house that's partly subsidized by the town. Steve is married to Charlotte, a former prenatal nurse, and has three kids. The last time the twins got in a fight with each other was 24 years ago. It began with a dispute over whose car they were going to drive into town for cash before heading back to St. Mary's College of California, where Mike played baseball. Mike's account of it has him spitting on Steve, then running and hiding in the bathroom, while Steve waited outside long enough to ambush Mike and punch him in the jaw.

Mike: “We busted up the house.”

Steve: “Oh, that's nonsense.”

Mike: “Haven't had a fistfight since.”

Steve: “I don't think I hit you in the face.”

Mike: “I guarantee you did.”

Steve: “I don't remember hitting you in the face, for crying out loud.”

Mike: “You did. Atrocious behavior. Unbelievable.”

I met Mike a couple of years ago, when he came to the Explorers Club, in New York, to peddle a rough cut of Skiing Everest, a documentary he'd made, with the filmmaker Les Guthman, about the twins' adventures. The film will be released this fall, after the Marolts return from an expedition to ski 26,758-foot Manaslu, in Nepal, the eighth-highest mountain in the world. The name of the film is a little disingenuous: It implies a descent from the top. Skiing on Everest doesn't have quite the same ring, however. This is the kind of thing that irks their detractors.

A number of renowned ski mountaineers told me, without wanting their names to be used, that they resented the attention the Marolts had received for their exploits—or, more to the point, the attention the Marolts had sought out. The criticism is that the Marolts ski (and climb) unremarkable, unstylish lines (“tourist routes,” as one put it), that they care less about summits than about altimeter readings, and that, above all, they make more of their feats than those feats merit. The fact that they've skied so often above 7,000 meters elicits a collective “So what?” from the sport's elites, who favor first descents and technical derring-do. One of them told me, “All it proves is that they have more time and money to waste on trying to get one boring run.”

The relative youth and narrowness of the high-altitude-skiing category makes it a hard niche to define and opens it up to a host of qualifying questions. Did the skier use Sherpas or supplementary oxygen, did he ski from the summit, did he make a continuous descent, did he choose a stylish route? One day, I came across a list of first descents assembled by the Colorado ski-mountaineering pioneer Lou Dawson (the first to ski all of the state's 14,000-foot peaks) on his blog, . It became an occasion, in the comments section, for a handful of the world's top ski mountaineers—including Fredrik Ericsson, Andrew McLean, and Dave Watson (who skied on, but not from the summit of, K2)—to engage in a spirited debate about the relative merits and murky facts of various high-altitude-skiing feats. McLean wrote at one point: “For better or worse, there are no rules to this sport, which leaves it open to interpretation when somebody shouts 'I SCORED A TOUCHDOWN!' That's when the real games begin.”

“There's a hell of a lot of ego in what we do. Let's be frank,” says Steve.

“When you go out and do all the shameless self-promotion,” Mike told me, “people think, 'Oh, Marolt's out there making money.' I haven't made a dime off of any of this, but I have been able to drag my buddies along on amazing trips around the world.” He helped finance the Shishapangma expedition by selling photographs of earlier trips. “Then we got the feather on Shish, and the sponsorship came around”—mostly in the guise of free gear. Still, Mike says, the trips are 75 percent self-funded. It's the films that require the money. To complete Skiing Everest, he got a big loan from a family friend. Fortunately, Mike had plenty of raw footage; he's brought a camera on all their trips and has learned, through trial and error, how to deploy it. These aren't home movies.

“The glory in what we're doing, if there is any, is just the result of one thing: We decided to do it,” Mike said to me one day. “Anyone can do it. It's doesn't require any special talent. It's not like hitting a major league curveball. It's not even a sport. It's high-level, high-risk recreation.”

WHEN I FIRST MET MIKE, I recognized the last name. It turned out that he and Steve were nephews of Bill Marolt, a former Olympic ski racer and director of the U.S. Ski Team. Bill's older brother, Max Marolt, Mike and Steve's father, had been one of the top ski racers in the world; he competed in the 1960 Olympics.

The family has deep Aspen roots. Mike and Steve's great-grandfather, Frank Marolt, an Austrian immigrant, had walked—walked—from Ohio to Colorado during its 1880s silver rush. The early Aspen Marolts were miners and barkeeps. In the 1930s, they began raising cattle. The family sold the Marolt Ranch, which encompassed 440 acres, in the 1950s for $157,000. It's now the municipal golf course. On the one hand, Mike and Steve can regret no longer having the land in the family, as it would now be worth many tens of millions; on the other hand, as Roger Marolt, Steve and Mike's older brother, says in Skiing Everest, selling the land gave their parents the means to remain in Aspen as it became a glitzy, expensive resort. “Growing up, they couldn't even afford to eat the cattle they raised,” Mike said of his forebears. Instead, they lived on what they could catch or kill: deer, elk, trout. This is why, later in life, the boys' father, Max, ate only beef. (Mike: “I can't eat trout.” Steve: “Worms with fins.”)

Max began taking the boys backcountry skiing on Independence Pass when they were 12. Once they could drive, they each bought a Willys Jeep and started heading out on their own. One year, Max, who made a living as a regional sales rep for Look bindings, Völkl skis, and Nordica boots, started an off-season ski-racing camp up in a backcountry cirque called the Montezuma Basin, at the foot of Castle Peak, where he'd often trained. Max put in three rope tows and converted an old smelting house into a bunk room. It didn't last long. The U.S. Forest Service made him shut down the rope tows because they fell within the Aspen Skiing Company's leased property, and someone burned down the bunkhouse. Still, the twins spent years exploring the nearby peaks and chutes. (Max died of a heart attack at 67, in 2003, while skiing in Las Leñas, Argentina—”with his skis on his feet,” as Mike says.)

Typically, in their Colorado backcountry wanderings, the Marolt boys were accompanied by a handful of close neighborhood friends, including Jim Gile, now a computer programmer, and John Callahan, a former Olympic cross-country ski racer. This was the core group that wound up graduating from one adventure to the next, until they came to find themselves gasping for air together in Tibet. The first trip out of state, after the Marolts graduated from college, was to Mount Rainier. Next came Denali, in 1990, where they realized they had a lot to learn. (They reached, but did not ski from, the summit.) For seven years, the group made an annual pilgrimage back to Alaska, to the Wrangell–St. Elias range, where they ripened their mountaineering skills on such beastly peaks as Logan, Blackburn, St. Elias, and Bona. At that time, it was a place where not many had skied. They left their skis behind on their first trip to Asia, the 1997 trip to Broad Peak. They were accompanied by the mountaineer Ed Viesturs, who got tired of hearing them grouse about not having their skis and suggested they bring them along next time. It was Viesturs who urged them to consider Shishapangma.

After Shish, and a series of trips to South America (they go down to the Andes every year), they got to Everest in 2003. They approached it from the north: It was cheaper to do so, and they wanted no part of the notoriously dangerous Khumbu Icefall. Foul weather and extreme cold prevented them from making the summit. “It's been 60 days, and north Everest has kicked our butts,” Mike said to at the time, via satellite phone. The Marolts wound up skiing a section of the North Ridge, from an altitude of 25,000 feet, in a storm that blinded them, helpfully, to the fact that on either side of the narrow pitch they were skiing were precipitous drops of 4,000 feet to the glaciers below. They settled for a similar result in 2007, on their return trip to Everest, when Mike, worried about his frozen feet and discouraged by thin snow cover, decided to turn back at 28,000. Earlier on the same trip, they'd climbed Cho Oyu, where Mike had an asthma attack a few hundred feet from the summit, preventing him from making the top. (Mike is also, bizarrely, allergic to aspen trees.) Steve alone skied from the summit.

Their Himalayan résumés, like those of most mountaineers, contain as many shortfalls as triumphs. Failure, if you can even call it that, is part of the deal. (Survival is success, of a kind. The only injury anyone has ever had on one of their trips was a frostbit fingertip, on Mount Logan.) For all of Mike's finely parsed categories of accomplishment, he insists they're in it for the turns, not the prize.

“I've never had regret about not making the summit of Everest,” he says. “When you're climbing those peaks, you don't care if someone's been there before you.”

MY FIRST DAY OUT with the Marolts was a tour in the Snowmass backcountry. It was May, and the lifts were closed, but there was still a lot of snow, all the way down to the ski area's base. Mike and Steve typically put climbing skins on their skis and hike up Snowmass and then on out to an adjoining peak called Baldy a couple of times a week, before or after work. They were inspired, in part, by Fritz Stammberger, a German climber who moved to Aspen when they were kids; Stammberger, who summited Cho Oyu in 1964 and then skied down from 23,600 feet—at the time, the high-altitude-skiing record—used to train by hiking up Aspen Mountain with duct tape covering his mouth. The Marolts skip the duct tape.

Unlike most ski mountaineers and backcountry skiers, who sneer at riding lifts, the Marolts also hit the resort a few afternoons a week, when it's open, to pound out as many runs as they can in a couple of hours before the lifts close. (Mike told me he couldn't care less about first tracks: “I've had plenty of powder in my life.”) They generally ski Ajax, which is a few blocks from their offices. (They are not business partners; they get enough of each other as is.) They use giant slalom racing skis and seek out bumps and crud. The idea is that the only way to build up the muscles for skiing at high altitude is to ski hard. No matter how fast you walk up, you can't get enough turns in without the chairlift. “You can't ski those peaks without doing that,” Mike said. “You need power and endurance.” Still, no bump run will really prepare your legs for Everest. “It's hard to pursue an anaerobic sport in a place where you can't go anaerobic,” he said.

Since I'd arrived, Mike had been needling me to come with them to Manaslu in September. And yet now, in consideration of the fact that I'd come from sea level, they'd arranged for a snowmobiler to rush us, one at a time, to the top of Snowmass. The WildSnow boys would not have approved. Mike rode up first, while Steve stayed behind with me and complained about how much he hates snowmobiles. I soon came to dislike them, too, when halfway up my pilot flipped our sled. I bailed (helmetless) just before the machine careered, upside down, into the pines. The driver had on a helmet and was unharmed, save for his pride. The 40-minute effort to get the sled upright made me aware, for the first time, of the altitude.

The day was sunny and clear. Up high, the wind had beaten the snow into meringue; the windward aspects were bare, the lee loaded. Once Steve joined us, cursing the sled, we skinned out along the ridge toward Baldy. About 15 minutes out, Mike dropped a ski pole. It skittered to a stop on a massive pillow of snow about 60 feet down the leeward cirque, which was also baking in the sun. Steve and Mike considered it for a while and decided that it was too risky to retrieve it; the pillow had a hair-trigger look. They tried throwing rocks at the pole, to knock it loose and down to the bottom of the bowl, for later and safer retrieval, but that didn't work. They'd have to come back for it in August. For the next two hours Mike skinned with one pole. I tried to think of all the people I'd skied with over the years and concluded that the twins, who venture into more perilous terrain than most of them, might be the only two who wouldn't have persuaded themselves to go after that pole.

Our day ended with a gentle corn run down through the Big Burn, amid the eerie ghost-town appeal of a resort hill shut down for the year. The day, snowmobile aside, had been as mellow as a backcountry outing can be, and yet after skinning for a couple of hours at 13,000 feet, I could feel the altitude getting the better of me. It was hard for me to imagine the horror of an asthma attack at twice the altitude, as Mike had experienced on Cho Oyu. Generally, asthma aside, Mike and his brother seem to be physiologically suited to high altitude: Doctors have told them that they have huge hearts and lungs and veins. On a treadmill at a MET testing site, Mike's VO2 max—the point during exercise at which the body can no longer increase the amount of oxygen it uses, despite the intensity of effort—was more than 70, double the average 45-year-old male's score.

“Our genetics allow us to have fun at altitude,” Mike says.

So does the fact that they have a ready-made expedition team in the half-dozen or so old Aspen friends who've been accompanying them for 20 years.

“When everything works, it's like a line on a hockey team,” Jim Gile likes to say. Gile also likes to say, at some point on every trip, that he will never go on another one. “He writes it in his journal: 'Remember this,' ” Steve says.

John Callahan told me that he wouldn't bother to climb at all if not for the company—rough as that company can play. Callahan, the Marolts told me, comes in for more flak than anyone.

Steve: “Why is Callahan the brunt of every joke?”

Mike: “Because he's a know-it-all. We call him the Professor.”

Steve: “Callahan failed calculus twice. In college.”

Mike, for his part, gets perennial hell for an old Rainier trip, their third, in which he decided, a few feet short of the summit, that he was close enough. “It comes up constantly,” Mike says. “It bugs the shit out of me, both because I was too lazy to go those extra 20 feet and because who cares? I'd already been to the top a couple of times.”

“THAT'S NOT his house.”

“Yes, it is.”

“No, it's not.”

“Yes, it is.”

“No, it's not.”

The twins were inching along an Aspen street in the dark in Mike's pickup truck, looking for the home of their friend Mike Maple, who accompanied them on an expedition to Noijin Kangsang, a 23,642-foot peak in Tibet, last year. (It was Maple who coined the term “Tibetan corduroy,” which is, as Mike described it, “a generous euphemism for corrugated boilerplate.”) It was almost 5 A.M. Maple appeared, and the three of them spent most of the drive south to the Castle Creek trailhead swapping tire-rotation horror stories and gossip about acquaintances who were having extramarital affairs. “You've hung out with these guys long enough to know not to believe everything you hear,” Maple told me.

First light found us walking up along a rutted jeep track over ice and rotten snow at about 10,000 feet. Sunrise came as we put on our skis and skins, revealing steep palisades of rock and snow rising up on both sides of the drainage. The Marolts pointed out prized lines. Up ahead, the valley forked where their father's ski camp had been. The Marolts decided to go for Pearl Peak, on account of the avalanche risk on nearby but higher Castle, if not also for the fact that they had along a flatlander who was already struggling to keep up. They led the way up into a vast basin of refrozen snow that rose gradually from the tree line to the foot of Pearl. We weren't even at 12,000 feet yet, and I was out of gas. The wind had a schizophrenic malevolence to it. Spring in the southern Rockies, my ass.

We boot-packed over scree and windblown snow up the face of Pearl, the two Mikes way ahead, Steve hanging back, tight on my tail, exhaling very loudly. (Mike told me later that Steve is a notorious heavy breather; the doctor's office under the Aspen gym where the brothers work out has lodged several complaints.) We reached the peak at ten and spent a few moments taking in the view of Crested Butte, as well as of Castle, which looked inhospitable from this side, too. Steve's altimeter read 13,300 feet. Now that it was time to ski, I felt fine. As Mike says in his film, “climbing without skiing is just pain and suffering with lousy food at the end of the day.”

We leapfrogged our way down a chute, the snow wintry and firm. It was steep and rocky enough to suggest that any kind of fall could mean trouble but wide enough to allow for a little speed. The Marolts skied with an aggressive, heavy style; you could tell they'd raced in their youth. After the run was done, we traversed across the basin over to an adjoining mountain called Greg Mace Peak and boot-packed up its flank to access another chute, which had the shape of an hourglass. “I thought New Yorkers were always in a hurry,” Maple said as the three of them waited for me to click in. The run was a dream. It started in steep chalk and ended in a giant alluvial field of corn snow that settled once and for all in my mind the utter insanity of ever walking downhill over snow.

“Once you make turns, it makes everything right,” Mike said back at the truck. It was noon. We'd ascended and descended 5,000 vertical feet in a morning. Usually, they'd have done it in a couple of hours. “You could have the experience from hell, but once you make turns—even if it's bad snow—it makes everything right.”

Agreed. But Manaslu? I'll pass.