“THERE WAS ABSOLUTELY NO DOUBT about it—can I go, can I not go. It was a clean decision. The snow was superstrong, superpositive. Fantastic.”

“I know what happened,” says Ruedi Beglinger, the guide in charge during the January 20 avalanche disaster. “It would be a different ballgame if I couldn’t figure it out.”

“I know what happened,” says Ruedi Beglinger, the guide in charge during the January 20 avalanche disaster. “It would be a different ballgame if I couldn’t figure it out.” “Nature wanted to hit us:” Beglinger choppers in to the Durrand Glacier Chalet nine days after the accident.

“Nature wanted to hit us:” Beglinger choppers in to the Durrand Glacier Chalet nine days after the accident.

The alpine dream: SME’s Durrand Glacier Chalet

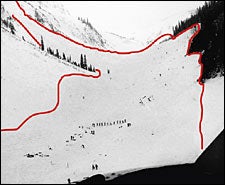

The alpine dream: SME’s Durrand Glacier Chalet Two hours after the February 1 avalanche (red outline), a probe line of rescuers (center) looks for survivors

Two hours after the February 1 avalanche (red outline), a probe line of rescuers (center) looks for survivors

In his lilting Swiss-German accent, Ruedi Beglinger, the founder and owner of Selkirk Mountain Experience (SME), a popular hut-skiing operation in Revelstoke, British Columbia, begins to describe the conditions five days earlier, on January 20—the day a large Class 3 avalanche killed seven of the 20 people he was guiding on a peak named La Traviata. “If I would have come home that evening with nothing having happened,” he continues, speaking quietly inside the third-floor office of his Revelstoke home, “I would say that today was the best day ever. Absolutely amazing snow. You can jump into that stuff with no worrying. Like a hardwood floor. But that’s not how it was.”

As fate would have it, the Revelstoke slide was just the start of a particularly brutal two-week period in British Columbia. On February 1, 12 days after the Selkirk avalanche and less than 20 miles away, another powerful slide claimed the lives of seven Calgary high school students on a school-sponsored cross-country excursion. Combined, the two accidents represented the deadliest fortnight in the history of North American alpine touring, prompting deep questions about ethics, risk, and the business of skiing the backcountry.

Despite the eerie similarities, these disasters involved very different circumstances. In the second incident, an inexperienced and young group passing through a high-traffic area was blindsided by a more-or-less random event. (See “Tumbling Down,” page 107.) In the January 20 avalanche, however, expert skiers who had signed on expressly to seek downhill thrills on exposed terrain were led by a guide with a flawless safety record. Both avalanches left devastated families, friends, and survivors in their wake. But the fate that befell Beglinger’s SME group seemed less purely accidental, and more subtly problematic, because it involved the judgment and decisions of a renowned backcountry guide—a man known for aggressively providing his clients with access to some of the most demanding landscapes on earth.

A 48-year-old from Glarus, Switzerland, Beglinger grew up skiing in the Alps, and in 1977 completed his Union Internationale des Associations de Guides de Montagne certification—the gold standard for mountaineering and skiing guides. Spare and of medium height, he is nearly inexhaustible in the mountains, spending 200 days a year in the backcountry, breaking more than a million vertical feet of trail for some 400 skiers a year. Beglinger’s customers must be prepared to push themselves mentally as well as physically—a day of skiing with SME usually involves seven hours, and the pitch of some powder runs approaches 50 degrees.

Furthermore, unlike heli-skiers and cat-skiers, SME clients climb every inch of vertical they descend. “It’s a chance to come out of your regular life and really go for it,” one skier told me. “Ruedi’s a real hard driver,” said another SME veteran. “He’s out to squeeze the last drop of skiing from the mountains.”

Such full-tilt charging at the winter backcountry, as well as Beglinger’s old-school European approach—in which the guide’s word is law, and you’re ready by 8 a.m. or you’re left at the lodge—aren’t for everyone. Some clients have called him “militaristic.” Others have even declared his style of probing the steep and the deep for more exquisite powder lines “a time bomb waiting to go off.”

The criticism hasn’t altered Beglinger’s style; it has, however, made him more willing to explain to weak skiers that his emphasis on speed, precision, and efficiency isn’t some autocratic power trip, but a crucial element in his approach to safety. “My style was learned in the Alps,” he says, “and is the one given by all big mountains.”

SME’S brochure doesn’t mince words about the ability levels required of customers. Skiers must be able to negotiate “rugged terrain” that is “very remote and wild”; safely link 20 turns down the fall line in deep snow and on slopes equal in steepness to black-diamond runs at international resorts; and climb at least a vertical mile each day of the trip. SME staff also conduct phone interviews to make sure skiers comprehend what’s involved. Up to two months prior to the trips, which last from four days to a week, guests are told, “If you’re not comfortable with any of this, you can back out and we’ll give you your money [about US$1,000] back.”

Until January 20, SME had never had a serious injury or fatality in 18 years of operation. Yet in the days immediately following the accident, the questions multiplied: Why were Ruedi Beglinger and his group skiing when the official avalanche forecast was “considerable”? Why were there 21 people in two groups on a single slope, with one group skiing above the other? Who—if anyone—was to blame?

“My guests are my friends, and I take care of my guests,” Beglinger tells me, on the verge of tears. “But on the 20th of January, at 10:45 a.m., I failed. And I failed not because I made a mistake. I think I failed because nature wanted to hit us.”

THE GROUP THAT SET OFF ON on January 20 was a strong one. In addition to Beglinger and 38-year-old assistant guide Ken Wylie, it included five SME staff. One of the staff members was snowboarding legend Craig Kelly, 36, who was training to become a certified mountain guide. There were 14 clients—three were returnees, and two others were part-time skiing and mountaineering instructors. Six of the clients were friends from Truckee, California; one of them, Rick Martin, a 51-year-old electrician, later noted that “most of us had 20 years of experience in the backcountry.” As always, SME had conducted transceiver and rescue drills with all the clients before embarking into the backcountry.

It was the group’s third day at the lodge. The skiers left at 8 a.m., with the temperature climbing into the low twenties as they glided along in single file. The pace was stiff, the mood buoyant. Beglinger led the skiers northwest toward 8,400-foot La Traviata and its 30-degree west couloir. Their original destination had been a peak called Fronalp, but the mountain was socked in. Conditions on La Traviata—with only high, broken clouds above—looked more favorable. The skiers had traveled in fog the previous day, and Beglinger wanted them to have a view.

Each avalanche season has its own unique meteorological history and risk profile, as weather and temperature build layers in the snowpack. In November, rain throughout the Selkirks had left an icy crust upon which moderate December snowfall did not bond. In early January, a warm spell triggered multiple avalanches that slid down that crust, but cold temperatures soon returned, and SME’s snow-pit, compression, and shear tests during the following two weeks indicated that conditions were stabilizing as the snowpack began bonding to the underlying ice. On January 17, Beglinger dug a test pit on a 45-degree, west-facing slope called the Goat Face, not far from the chalet, and he could no longer find the dangerous November layer. Moreover, for the past two weeks the Canadian Avalanche Association had pegged the risk of avalanche around the Durrand Glacier at “considerable”—a midlevel rating, and one that generally doesn’t deter guides from taking groups out.

About two hours after departing the lodge, the group reached the bottom of La Traviata and entered the west couloir. Beglinger put in four switchbacks to the top, where the slope eased off to a bench below the summit ridge. Probing along the way, he found excellent conditions.

“Not one hollowness,” he said later, “not one little bit of a crust that I picked up. It was beautiful. As good as it gets.” Rick Martin, third in line behind Beglinger, also remembers seeing nothing on the way up that made him nervous. “There were signs of old activity, but none of the classic signs of avalanches,” he says. “No cracks. No whumping. I saw no windloading. I considered it pretty ordinary.”

The skiers were traveling in two groups: 12 of them following dutifully behind Beglinger near the top, and seven others, led by Ken Wylie, just beginning the first traverse.

Following in Beglinger’s tracks, Martin exited the gully onto a gently sloping bench and moved right, away from the slope beneath him. He joined Beglinger and a client named Age Fluitman, who had paused on an almost-flat spot below the ridge to let the rest of the group catch up. Not too far below, but still on steep ground, were Jean Luc Schwendener, a 40-year-old chef from Canmore, Alberta; Evan Weselake, a 28-year-old corporate trainer from Calgary; Craig Kelly; Naomi Heffler, 25, a canoeing guide also from Calgary; and Dave Finnerty, a 30-year-old SME trainee from New Westminster, B.C., bringing up the rear.

When Weselake had nearly reached the top of the couloir, he stopped and looked back to observe the lower group’s progress. He saw Wylie, the guide, about halfway across the bottom of the slope, with the others trailing, and then he returned his concentration upward.

There was no warning for what came next. Beglinger, standing on his perch above the couloir, felt a sudden huge settlement almost directly beneath him, not anything like the normal whump experienced by countless backcountry skiers. Then he heard a percussive explosion. “Unbelievably loud,” he says.

JUST MOMENTS LATER, Weselake saw a crack open in the snow uphill from Schwendener. Then a second fracture line ripped between them, and the world began to move.

Weselake yelled, “Avalanche!” and was reaching down to release his telemark bindings when the moving slab pushed him over. Schwendener, Kelly, Heffler, and Finnerty were also caught and began moving down the slope. Weselake tossed his poles aside, lay on his back, and tried to swim as everyone and everything around him disappeared in a maelstrom of snow.

Below, third in line in the lower group, was John Seibert, a 54-year-old geophysicist from Wasilla, Alaska, who was on his eighth trip with SME and had skied this very slope a year before. He heard what he later described as a “shotgun blast” and, a millisecond later, a “whump.” As the slope began to move, Seibert tried to turn and ski off it to safety, but the slide knocked him on his butt. “I backstroked from here to eternity,” he said, “and in my peripheral vision I saw the slab breaking up into blocks. It was like being in big whitewater. I never lost sight of the sky. It didn’t slow down. I thought I was going to get my hands in front of my face to make an air pocket. But it stopped instantly. The snow was level with my neck, and my head and my left hand were sticking out.”

The three skiers at the end of Seibert’s group, all of them SME employees, had managed to turn in the track and were trying to ski toward the side of the gully when they were overwhelmed by the slide and buried. Also engulfed were Wylie and three clients: Vern Lunsford, 49, an aerospace engineer from Littleton, Colorado; Dennis Yates, 50, a ski instructor from Los Angeles; and Kathleen Kessler, 39, a realtor from Truckee.

Now completely submerged, Weselake felt the slide abruptly come to a standstill as the leading edge of the avalanche halted in a depression at the bottom of the slope. Blocks of snow were wedged around his head, and he could see dim light and take rapid, shallow breaths. But he was locked tight in the debris, unable to move anything except his right ski tip. He tried not to panic. He remembers thinking, “Relax your body, slow down your breathing, and just wiggle your ski.”

FROM HIS VANTAGE POINT ABOVE, Beglinger watched the avalanche roar to life. After the explosive noise, he recalls, “It was quiet for maybe a tenth of a second, and then it was like a rocket went down the slope—woosh-shoo!—accelerating as it went. The ground started to vibrate, and I realized that the energy was going behind me to the west.”

The first slide set off a second, smaller avalanche—still to the right of the ascent track. But then a third, huge split opened up high in the chute above Ken Wylie’s group, and the entire couloir washed down the mountain.

Beglinger whirled around and ran over to get a better view down the couloir, yelling into his radio as he went, “Durrand Glacier Chalet from Ruedi! We have a terrible accident! I need all help there is!”

He looked past the crown of the avalanche and saw a nightmare. Twenty-one skiers had started out that morning from the chalet; 13 were now buried below.

“It’s huge!” Beglinger shouted into his radio. “Everybody’s down! We need all help there is. Nobody on standby, everybody coming up here. Selkirk Tangiers, CMH, Department of Highways, avalanche-dog masters, paramedics, and everything you can find—bring it up!”

The cook at the Durrand Glacier Chalet fielded the call and handed it over to Beglinger’s wife, Nicoline. The call was also picked up by Ingrid Boaz, a part-time SME employee in Revelstoke, where radio communication is constantly monitored. She radioed Selkirk Mountain Helicopters and reached Paul Maloney, one of the pilots, who happened to be in the air about 28 miles away. Maloney sped toward the chalet, where he picked up two guests, extra shovels, and a trauma kit.

On La Traviata, Beglinger jumped over the crown and glissaded down the icy bed surface of the avalanche. “I was talking on the radio,” he says, “and with the other hand I took out my beacon, put it on receive, and as I came to a stop, I threw the radio inside my jacket, picked up the first person, flagged him with a probe, went over, picked up the second person, put a pole in, the third person, put a pole in, and that was like two minutes from when the avalanche cracked loose.”

With all the SME staff except for Beglinger buried by the avalanche, it fell to the clients to aid in the rescue effort. Charles Bieler, a 27-year-old skier from New York City, reached Seibert, who was trapped but uninjured.

“Are you OK?” Bieler asked. “Can you breathe?” After Seibert indicated he was all right, Bieler told him, “We’ve got a lot of people buried—we’ll get to you as soon as we can.” Another client—Seibert can’t remember who—reached down and turned Seibert’s avalanche beacon to receive, so it wouldn’t confuse the search, and handed Seibert the shovel from his pack, which he used to dig himself out. He stood up and saw a sea of debris, packs, skis, and eight members of the group searching, probing, and digging. He joined the rescuers and began pitching in.

Evan Weselake, locked in blocks of hard snow, was still wiggling his ski tip, which was protruding above the surface. One of the clients, Bruce Stewart, 40, a skier from Truckee, noticed it and dug him out. Weselake paused long enough to put on heavier gloves and then began searching with his transceiver, finding a signal only 2.6 meters away from the hole he’d just climbed out of and 1.2 meters below the surface. “Those numbers will be burnt into my memory forever,” he told me. “It was Jean Luc.” He yelled for a shovel and Beglinger appeared. The two of them frantically began to dig, but when they finally reached Schwendener, he was dead.

Meanwhile, Rick Martin had ripped off his climbing skins and skied down the bed surface of the avalanche. He located a victim and began to dig, eventually uncovering Naomi Heffler’s face and chest. Heidi Biber, a 42-year-old nurse from Truckee, performed CPR—to no avail.

After several rescuers succeeded in digging down to Dave Finnerty, they lowered Biber into the hole by her ankles. She again attempted CPR, but Finnerty did not regain consciousness. When the bodies of Vern Lunsford, Dennis Yates, and Kathy Kessler were uncovered, efforts to revive them were also unsuccessful. Craig Kelly, lying lifeless almost nine feet below the surface, was the last victim removed.

In the end, six of the skiers who had been buried were saved, including the three SME employees from the lower group. Ken Wylie also survived—barely. After finding his signal, rescuers first uncovered Wylie’s hand, then cleared away the snow around his head. His cheeks were still pink, and Seibert felt his carotid artery and detected a pulse. Beglinger, who was trying to reach another victim, remembers that a great shout went up behind him: “We got Ken!”

“I cleared his airway,” Seibert said. “I don’t recall if I gave him a breath or two. We were talking to him, saying, ‘Wake up!'”

But then Wylie’s head rolled back. Joe Pojar, one of the SME staffers, jumped into the hole and slapped his face hard. “Ken!” he yelled. “Hear me! Let’s go home!” Wylie opened his eyes and started to breathe.

ROUGHLY 40 MINUTES after Beglinger radioed for help, Paul Maloney, the Selkirk Mountain Helicopters pilot, flew his chopper under the lowering fog and landed at the base of La Traviata. Moving fast, he flagged a landing zone for three more helicopters, two from SMH and one from Selkirk Tangiers Helicopter Skiing.

Wylie was flown to a hospital in Revelstoke. At the avalanche site, Beglinger stood in the debris field, despair over the general disaster only now beginning to descend on him. One failure was particularly haunting: his attempt to save Vern Lunsford. “He was only 1.2 meters down,” says Beglinger, “and I felt I would find him alive. I was hoping because the snow was soft. Then I hit a great block of ice. He wasn’t alive when I reached him.”

The survivors, exhausted, in shock, some beginning to break down, were flown back to the chalet. There they would try to console one another while taking turns on a satellite phone to call their families. Most of the next of kin were notified by police in Canada and the U.S., but Heidi Biber personally made the hard call to Scott Kessler in Truckee. In tears, she told him there had been a devastating avalanche, and that his wife, Kathleen, had been killed.

Before any of the survivors had even returned to Revelstoke, where a makeshift morgue had been set up, wire-service reports—patched together from talking to the B.C. Ambulance Service and the helicopter operators—began to filter out. The earliest of them declared eight Americans dead, then seven, then the correct figures: three Americans and four Canadians. E-mails shot back and forth within the skiing community, and within 24 hours at least 30 print and broadcast journalists, photographers, and TV cameramen had swarmed over the small Wintergreen Inn, the main base camp for SME clients.

Most of the survivors wouldn’t speak publicly about the incident, but John Seibert, acting as spokesman for the group, appeared at a press conference at the Royal Canadian Mounted Police office on January 21. While his companions attended a grief-counseling session at the inn before quietly slipping away, Seibert told reporters and the police that the avalanche was “a fluke of nature.” The same day, in what seemed like a clear attempt to quell the rising storm of media speculation—What happened up there? Was someone at fault?—the RCMP released a statement that said, “There is nothing in the initial investigation at this time to lead investigators to believe that this is anything other than a tragic accident.”

LIKE MANY PEOPLE in Revelstoke’s snow-science and law-enforcement communities, Clair Israelson looks puffy-eyed and tired three days after the accident. As the managing director of the Canadian Avalanche Association, Israelson, 53, has been helping the B.C. coroner’s office with the investigation into the SME incident and, a few days later, the avalanche on February 1. Official reports won’t be out until the end of May, and, with the newspaper and TV reporters temporarily gone, Israelson gets a rare moment to sit back in his map- and file-cluttered office to explain his job’s complexities.

“I believe we can forecast avalanche danger and snow stability at a mountain-range scale with a reasonable degree of confidence,” he says. “What we can’t do is forecast for every slope on every mountain in that range with a high degree of confidence. And so the art of guiding is moving safely through dangerous places.”

Of course, this is what guides do every day of the winter in British Columbia, the risk of “considerable” avalanche danger notwithstanding. As Israelson points out, considerable is only halfway up the five-level International Avalanche Danger Scale, which begins at low and moderate and ends at high and extreme. If people stayed home when the avalanche danger was considerable, no one would go skiing.

Guides base their decisions to go or stay on an aggregate of factors, including recent weather history, their own experience with the terrain, on-site testing, and daily regionwide data gleaned from the Information Exchange—a report compiled by guides, heli-operators, highway departments, and national parks logging every observed avalanche in western Canada. The January 20 Information Exchange showed a particularly quiet day in the region: only eight avalanches triggered by explosives, and two small ones triggered by skiers. On an active day, there would be pages of avalanches reported.

So if the slope was stable, why did it go? “The problem is that unstable conditions can sit way out on the end of the bell curve, a couple of standard deviations away from the mean,” says Israelson. “They’re there; we know it. But despite our best science, we haven’t found the means to forecast them.”

In Beglinger’s case, when he reached some shallow snow—maybe 20 inches deep—on the ten-degree upper slope of the ridge, it settled over the old November rain crust. That settlement started the initial avalanche and set up a domino effect, sending energy toward the skiers and triggering the massive third slide, which buried them.

The day after the accident, Larry Stanier, an independent avalanche expert from Canmore, Alberta, hired by the B.C. coroner, traveled to the site. He measured the slope angle at the crown: 33 degrees, not something experienced backcountry skiers would think particularly steep. He also did several compression tests, which evaluate weak layers in the snowpack that might be prone to being triggered by a skier. He tells me that he got a “very hard” result, which means that the slope wasn’t likely to slide from skier traffic.

“Ruedi ascended in the strong snowpack, and he wasn’t in the fall line above the skiers who were killed,” Stanier says, “but he managed to find the needle in the haystack.”

STANIER’S POSITION corroborates the eyewitness accounts of Keith Lindsay, Evan Weselake, and John Seibert. Nonetheless, the configuration of skiers on La Traviata put 13 people in harm’s way simultaneously, and, as the quick-to-condemn pundits of Internet ski chat rooms were alleging within hours of the accident, this equaled a “major fuckup.”

The logistical realities of guiding large commercial groups tell a different story. It isn’t atypical in the heli-skiing industry to have a dozen or more skiers at the bottom of a run when the next group begins down. As Alison Dakin, one of the owners of Revelstoke-based Golden Alpine Holidays, which began backcountry powder tours in 1986, says, “Unless you have a concern about a slope, you won’t spread your clients out. It takes a lot of time, you can’t keep your day going, and your clients get cold.”

The operative words here are “unless you have a concern.” Backcountry skiers pay people like Beglinger and Dakin to make those calls. And when things do go very wrong, as they did on January 20, should the guides be held criminally negligent?

A 1996 British Columbia Supreme Court case helped establish some legal precedent. In 1991, nine skiers were killed in an avalanche on a run called Bay Street, in the Bugaboos—still the largest single-day ski accident in the history of the province. A victim’s widow sued the operator, Canadian Mountain Holidays, and the guide (the only skier struck by the avalanche who survived), claiming that the guide had not dug a snow pit before attempting the run. She also maintained that it should have been obvious to any competent guide that there was a potential for deep-slab instability in the snowpack, since the slide ran down a deep, weak layer.

After extensive testimony from a variety of snow-science experts, a Supreme Court judge concluded that it was the assessment of all the CMH guides on the day in question that there were no concerns about deep-slab instability. Since this was the consensus, and it was extrapolated from a season of observing the snowpack, it wasn’t deemed reckless, dangerous, or even a marked departure from standard operating procedure to not dig a pit before attempting the run. Even though the slope did slide, the judge observed, “Liability…will only arise where a defendant has transgressed the standards to be expected of a reasonable man, not where he has acted with due care but nevertheless made what turned out to be a wrong decision.”

One of backcountry skiing’s well-kept secrets is that skiers get caught in avalanches with fair regularity, though they are often small and rarely fatal. Because the hazards can never be eradicated, SME, like other operators, maintains rigorous standards to protect its patrons and its employees. The company’s waiver—which all clients sign in the presence of a staff person—is laboriously explicit about the hazards of wilderness skiing, including the fact that guides “may fail to predict whether the alpine terrain is safe for skiing or whether an avalanche may occur.” The waiver was crafted by Robert Kennedy, an attorney who represents all the ski areas in British Columbia and who has successfully defended at least a dozen previous claims brought against other operators. It continues to be the primary document establishing that paying customers understand and accept the risks they are about to encounter.

At press time, there was no indication that any of the victims’ families were filing suit. In fact, the response, both from other outfitters and from grieving survivors, has largely been supportive rather than derisive or litigious.

“I respect Ruedi’s judgment and how he transfers it to his guiding style,” says Jim Bay, 50, who owns Mountain Light Tours, another backcountry operation in Revelstoke. “He has an admirable safety record if you look at how many skier days he’s put through his operation since its inception. Over the years he’s done a remarkable thing up there, and it would be a real shame if this incident colors it in a negative way.”

As for potential lawsuits, Kennedy says, “I haven’t heard a whisper of a notion that there may be a claim arising out of this. Just the opposite. There’s been an outpouring of sympathy for Ruedi from the next of kin.”

“I don’t think it’s anyone’s fault,” says Kathleen Kessler’s husband, Scott. “Spreading blame will do no good. Risk is part of being in the backcountry, part of doing something that you love. At Kathleen’s memorial service, I spoke, and I said, ‘Hey, all you folks who went out and did something this morning? That’s what Kathy would have wanted.'”

BEFORE BEGLINGER LEAVES for his first funeral—Vernon Lunsford’s, in Denver—we have dinner at his home in Revelstoke. Nicoline makes raclette, served with thick brown bread, pickles, sweet onions, and wine. The atmosphere reminds me of their Durrand Glacier chalet, the smells rich, the table elegant, his two young daughters, Charlotte and Florina, politely passing the dishes, Nicoline lovely and gracious.

This is part of what clients pay for when they sign up at SME: not only great powder, but also the chance to experience—if only for a week—the alpine dream created by this Swiss family. John Seibert has told me, “I’m positive I’ll go back and ski at SME again.” Rick Martin was also unequivocal that he would return—not only to SME and the Selkirks, but to skiing challenging lines.

They are not alone. The backcountry skiing community has grown tremendously as ski areas have become more crowded and expensive. Black Diamond Equipment Inc., based in Salt Lake City, has seen the sales of its alpine touring gear increase 20 percent a year for the last five years. Those rising numbers correlate with problems occurring off-piste: In the U.S., during the two seasons from 2000-2002, ten backcountry skiers were killed in avalanches. During the previous six years, avalanche deaths among backcountry skiers had averaged only one per year.

In British Columbia, the popularity of the backcountry has helped turn guided skiing into big business. According to a survey of the British Columbia Heli and Snowcat Skiing Operators Association, 28,000 skiers took a backcountry trip during the 2000-01 season in B.C., pumping an estimated US$68 million into the province’s economy—most of it from visiting Americans and Europeans. Heli-accessed huts create an additional tourist engine not reflected in the BCHSSOA study.

And the risk? Of the 28,000 heli- and snowcat skiers in B.C. during the 2000-01 season, three died in avalanches. Among heli-accessed operations, until this January nobody had been killed in 17 years. Disasters like those on January 20 and February 1 give the perception of high risk, but statistically speaking, it’s not supported by the numbers. “It’s horrible,” says Beglinger when we talk later, referring to the February 1 slide, “but they just got nuked from above.”

Before I depart, I ask Beglinger if anything will change now, after his accident. “Maybe we cut the groups back from 12 people to eight,” he says. “Less pressure. We will have to charge more, but I think even charging more, people will still come.”

“I know what happened,” he continues while walking me down to the end of his long driveway. “It would be a different ballgame if I couldn’t figure it out. I would be scared of guiding if there had been a bad layer I did not see and I just jumped onto it. But that was not the case. I had a conservative approach of the gully. I chose a self-supporting gully instead of a headwall. I choose the terrain feature which is in my favor instead of something exposed, and I did not trigger that gully. We had a settlement away from this. It fired into a different slope, and wrapped around the mountain and multiplied many times.”

We stand with the snow falling on us; the forest smells moist and sweet. He can’t talk anymore. He seems spent, and much lies ahead. Jean Luc Schwendener’s family will be arriving in an hour. Ken Wylie wants to debrief an hour after that. Tomorrow, Beglinger will be on a plane, bound for memorial services.

Before I leave, he offers a hopeful goodbye: “Until better times and happier skis.” He shakes my hand, turns, and climbs the drive, head bent, scuffing at the snow with his boots, his despair just peeking through the surface, but under control. It’s a large part of who he is—who he has to be, to move people through the shifting dangers of the alpine world. It is the side of him so many have seen and probably many more will view. But it’s not Rick Martin’s memory of him. Boarding the helicopter for the flight to the chalet after the rescue, the Truckee skier looked back and saw the seven bodies of his companions lying on the debris. Beglinger was sitting among them, weeping.

ON FEBRUARY 1, just 12 days after the Selkirk Mountain Experience disaster, seven high school students from Calgary died when their group was slammed by an avalanche just a few miles east of the first accident. The students were starting a three-day telemark ski trip at Rogers Pass in British Columbia’s Glacier National Park. Though the avalanche risk had been rated “considerable” in the heights above the trail, more than 80 other skiers had safely taken the path earlier that day.

The slide, triggered by a natural event, began nearly 3,000 feet above the skiers. By the time it swept over the group of 17, it was a massive killer more than 1,500 feet across. Nearby skiers and rescue personnel managed to pull ten people safely from the debris, but six boys and one girl, aged 16 to 18, perished.

In the aftermath, emotions ran hot, especially since these were teenagers on a school-sponsored wilderness trip, not adults actively courting danger on steep, hard-to-reach slopes. “These aren’t just accidents anymore,” declared the Calgary Herald the next day. “This is backcountry carnage.” Some parents felt the group shouldn’t have been out there at all, given the risk. And at a February 4 funeral, a grandparent one of the victims, questioned the very nature of such outings: “What kind of character are we trying to build by this type of adventure? Rambos? Conquerors?”

Would legal action come next? Rumors quickly started flying about a class-action lawsuit on behalf of survivors and families, although experts say such cases are difficult to win, given that the students’ parents had all signed liability waivers and no apparent safety procedures were violated. Meanwhile, the school—an elite private academy called Strathcona-Tweedsmore—is standing behind the judgment of the two teachers, Andrew Nicholson and Dale Roth, who led the trip. Both had avalanche training, and everyone in the party was equipped with beacons, shovels, and probes.

One thing is certain: the accident will be exhaustively investigated, and probes are already under way by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, the Revelstoke coroner’s office, and Parks Canada. In the aftermath, government officials were promising better avalanche warnings, a “comprehensive review” of wilderness safety, and a look at whether some backcountry areas should be closed when conditions are deemed too dangerous.