One winter night in 1995, in a crowded Jackson, Wyoming, bar, Stephen Koch ran into a friend who, like many of his friends, was also something of a rival—a fellow player in the rarefied, hyperdangerous sport of ski and snowboard mountaineering. Over a pitcher of beer, the two made a curious discovery: Both had quietly been eyeing the same virgin line, a finger of snow snaking precipitously down the northeast ridge of Wyoming’s 10,267-foot Cody Peak. The route had all the right stuff: It was narrow, scary-steep, and ended abruptly at a 350-foot cliff. Better yet, it was plainly visible from the base of nearby Jackson Hole Mountain Resort—and whoever got down it first would not be toiling in obscurity.

Stephen Koch at Jackson Hole Mountain Resort, January 5, 2003

Stephen Koch at Jackson Hole Mountain Resort, January 5, 2003 Cold feet: Koch at Granite Falls, in Teton National Forest.

Cold feet: Koch at Granite Falls, in Teton National Forest. One way down: Koch plots his Everest finale on Jackson Hole’s Rendezvous Peak in January.

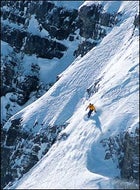

One way down: Koch plots his Everest finale on Jackson Hole’s Rendezvous Peak in January. Total commitment: Koch makes his pioneering descent of Talk Is Cheap, March 1, 1995.

Total commitment: Koch makes his pioneering descent of Talk Is Cheap, March 1, 1995. “I just want to swing ’em”: Koch in full quest mode at Jackson Lake, in Grand Teton National Park, not far from the site of his near-fatal avalanche accident in 1998

“I just want to swing ’em”: Koch in full quest mode at Jackson Lake, in Grand Teton National Park, not far from the site of his near-fatal avalanche accident in 1998The way Koch tells the story, his friend made a bold announcement on his way out of the bar. He was, he said, going to ski the route first thing in the morning. Koch, who at the time was earning a living busing breakfast tables at Jackson Hole’s Alpenhof Lodge, could only nod and feign a smile. “Great,” he said. “When I get off work I’ll come check out your tracks.”

It was noon the next day by the time Koch and a photographer pal made it to the summit of Cody after a 45-minute climb from the top of the ski area. To their delight, the northeast ridge was untracked. Wasting no time, Koch clipped into his snowboard, cinched the leashes of his ice axes, and dropped in. At the cliff band, he pulled out a rope and made a short, tricky rappel into an adjacent couloir, then put his board back on and finished the 4,000-vertical-foot run in style. It was an elegant first descent—Koch’s tenth in the Tetons—and by the time he got back to town he’d come up with a name for it: Talk Is Cheap, a not entirely playful jab at his rival. In the supremely macho game of getting there first, Koch seemed to be saying, there was no room for spewing—your tracks either were there or they weren’t.

It’s one thing to spout fiery credos as a youth, but it’s quite another thing to live by them forever after. And that, in a nutshell, is the dilemma of Stephen Koch.

Ten years ago, with a good deal of fanfare (and the subsequent collaboration of just about everybody in the adventure-sports press), a brash 24-year-old Koch announced his Seven Summits Snowboarding Quest—a bid to snowboard the highest peak on each continent. “I realized it was something sponsors and the media could understand,” says Koch, now 34. “Plus it seemed like a pretty good way to see the world.” Had things gone according to plan—he originally envisioned a three- or four-year time frame for the project—his quest would be a colorful footnote to the history of 20th-century mountaineering.

But in the mountains, things rarely go the way you want them to. There were technical glitches—on Koch’s first visit to Alaska’s 20,320-foot Mount McKinley, in 1993, a problem with his bindings made turning on steep, hard snow impossible, and he took a serious slide on a warm-up run above base camp. A bigger problem was the fickle public. Even though interest in mountaineering exploded after the Everest debacle of May 1996, Koch’s quest, with its focus on other, more obscure peaks, never quite caught on, and his sponsors, who at one time included such industry powerhouses as The North Face and Burton Snowboards, gradually drifted away. By the end of 1997, Koch had collected only four of the Seven Summits: South America’s 22,834-foot Aconcagua, Europe’s 18,510-foot Elbrus, Africa’s 19,340-foot Kilimanjaro, and McKinley.

More significantly, Koch himself was changing. Though he’d originally wanted to get to the tops of peaks merely to ride down them, he found himself increasingly drawn to “pure” alpinism—so much so that today, he admits, he prefers climbing to snowboarding. That’s Koch you saw on the cover of the 2002 American Alpine Journal, leading a delicate traverse on the Mini-Moonflower Buttress of Alaska’s Mount Hunter—one of a trio of extraordinarily difficult rock-and-ice routes that he and Slovenian climbing partner Marko Prezelj completed in June 2001. (The two were nominated for the Piolet d’Or award, the climbing world’s equivalent of an Oscar, for the last of the climbs, a route on McKinley’s southwest face they dubbed Light Traveler.)

Yet for all his success in this new arena, Koch the snowboarder has soldiered on, goaded, he says, by one overarching fear. “I’ve been talking smack about this thing for ten years,” he explains. “I need to finish what I set out to do. I’d feel like an idiot if I didn’t.” Despite a near-fatal avalanche accident in the Tetons in April 1998, Koch knocked off two more of the remaining three summits: Antarctica’s 16,067-foot Vinson Massif, in December 1999, and, in February 2001, Irian Jaya’s Carstensz Pyramid, at 16,023 feet the highest point in Oceania (and 8,700 feet higher than Australia’s tallest mountain).

It was never Koch’s intention to leave the toughest challenge—Mount Everest—for last. He was none too pleased when, in October 2000, Slovenian alpinist Davo Karnicar retraced the standard south-side climbing route from summit to Base Camp without removing his skis—the first unbroken descent of Everest. Ditto the following spring, when young French snowboarder Marco Siffredi pulled off an even more impressive feat, dropping off the summit onto the mountain’s precipitous North Face before traversing out to regain the North Col.

Now that Everest has been skied or snowboarded from both sides, what once loomed as a glorious finale to Koch’s quest is no more. Or is it? What Koch wants to do—or has persuaded himself that he has to do—is not to merely snowboard the peak. Late this summer, he will attempt to climb and ride its steepest and most terrifying route, the Hornbein Couloir, an avalanche chute that plummets nearly 10,000 feet straight down the middle of Everest’s North Face, on the Tibetan side of the mountain.

How dangerous is the Hornbein? To date, only one man has tried to descend it on skis or a snowboard: Siffredi, who returned to Everest in September 2002 in hopes of picking off the mountain’s ultimate plum. According to the Sherpas who helped the Frenchman carry his board to the summit on September 8, the 23-year-old was relaxed, rested, and carrying a full cylinder of oxygen when he dropped off the lip and began his descent. He was never seen again.

AT SIX-TWO, 185 POUNDS, Koch is big by the standards of the climbing and snowboarding worlds. With his linebacker shoulders, jutting jaw, and skinhead-short blond hair, he could be a cartoon character: Sergeant Rock in snow camo, or “El Gringo con Carne,” as he was dubbed on a 2000 snowboard-mountaineering expedition in Peru that we’d both joined. He exudes nervous energy. The first time I set foot in his Jackson apartment, a few weeks before Christmas 2002, I find him on hands and knees, madly scrubbing at a spot of mud left by a careless visitor. About the only time you’ll see him relaxed is on his snowboard, where he moves with serenity and perfect balance—a classic old-school rider.

A big key to Koch’s success is that while he is a physical machine, he’s also a social animal. He makes a point of striking up conversations with total strangers. He asks waitresses to show him their tattoos. He makes unnervingly direct eye contact, flashes his cat-who-ate-the-canary smile, and then crushes your hand in his. He’s a big hugger, which can be corny, but it’s usually charming, too. On McKinley a couple of years ago, conniving to meet two women climbers on vacation from jobs at Sony Music, he approached with a pressing technical question: Could they help him fix his broken Discman?

In a Huaraz, Peru, disco, I’d gotten a glimpse of Koch in full roar, stripping off his shirt when the beat picked up and clearing a huge swath on the dance floor. When I catch up with him in Jackson, he isn’t in quite the same form—his right knee is still tender from ligament surgery two months ago. But it’s party season, and Koch never misses a party. Toward midnight of my second night in town, we find ourselves in the Old Yellowstone Garage, a Jackson restaurant where the local oral surgeon is hosting a lavish holiday fte. Koch is dressed nattily, as usual—crisp chinos and a long-waisted Cuban shirt—and he works the room like a seasoned pro. Having been a fixture at the elite local outfit Exum Mountain Guides for more than a decade, he’s a well-known figure in Jackson, and most people have heard about his upcoming Everest plans. One woman in a black sleeveless blouse, however, has not. When he brings her up to date, she crosses her arms in disbelief.

“You can do that?” she asks. “Isn’t it, like, way too steep?”

“Not really,” says Koch. “I mean, I’ve been on steeper stuff here.”

If Koch has any doubts about the project, he doesn’t let on. Mark Newcomb, 36, a Jackson ski mountaineer and likely Everest teammate this summer, marvels at Koch’s ability to radiate confidence. “I can’t just go tell somebody I’m going to ski Everest,” Newcomb says. “I have to say, ÔWell, I’m going to try, but it might not happen.’ Stephen isn’t like that. He can look somebody in the eye and say, ÔI’m going to snowboard Everest.’ ”

Overhearing the conversation, a balding thirty-something PR executive and amateur climber joins in. “What route are you doing?” he asks Koch.

“The direct North Face,” says Koch. “The Hornbein.”

“Wow,” says the man, his eyes widening. “We were on Cho Oyu last year, and we got a good look at it. It’s steep—you’ll have to rappel some sections.”

Koch shakes his head. “I don’t think so. I’m going at the end of the summer, during the monsoon. It should be filled in.”

“And you’re going to climb that thing with all that snow?”

“That’s the thing that everybody forgets—like Marco,” Koch says of Siffredi’s attempt. “He went up the North Ridge and dropped in from above, and I really think that was part of the problem.” Siffredi used oxygen and support Sherpas, Koch explains, but he wants to do it “by fair means”—no oxygen, no Sherpas—and in true “alpine style”: straight up, straight down. “That’s the purest way,” he says. “And also the only way you know for sure what the snow is like.”

“Wow,” the man says again, shooting Koch a sideways glance.

Talk to Koch’s oldest friends in Jackson and you often see the same look. Most express support for the project, but it’s not hard to read the worry in their eyes. “I wonder if he feels like he’s pounded himself into a corner and needs to get this out of the way so he can say he did it,” says Jack Tackle, 49, a fellow Exum climbing guide and a veteran of many Alaskan epics. “Which isn’t the best place to be, psychologically, on a project of that scale.”

Others are less charitable. “I wouldn’t want to be in his position, I can tell you that,” says John Griber, 37, another snowboard mountaineer from Jackson. “If I go to Everest, I don’t have any obligations. If I’m 200 feet from the summit and need to turn around, I can turn around. Can he?”

When I report the comments to Koch, his face tightens. “When you get up there on the mountain, there are no sponsors,” he says. “And anyway, nobody could possibly put more pressure on me than I do.”

ONE DAY IN THE LATE 1980s, Jackson photographer Wade McKoy was shooting at Corbett’s Couloir, the dramatically corniced chute near the top of Jackson Hole, when Koch showed up. “This kid on a snowboard told me he was going to air it and could I take a few pictures,” McKoy recalls. “I didn’t see him again for months, until one day he came up to me and said, ÔHey, I saw my picture in TransWorld Snowboarding, but not my name.’ I said, ÔThat’s because I didn’t know it.’ And he was like ÔWell, that’s not good.’ ”

It’s not hard to trace Koch’s “powerful need for attention,” as he puts it, to his childhood. Koch grew up in San Diego, the fourth of five children of an aerospace engineer—his dad designed rocket wings for General Dynamics—and “a very religious mom,” a devout Catholic who sometimes organizes prayer support meetings when her son goes on an expedition. Seven years younger than his twin brothers and three years younger than his sister, Stephen often felt the kid brother’s sense that he was missing out on the action. A natural athlete, he made up for it by showboating in his favorite sports: skateboarding and surfing.

There’s a tradition of contemplative public service in the Koch family: One of the Koch twins is now a Benedictine monk in California; Stephen’s sister, who lives in Oregon, counsels compulsive gamblers; and his younger brother did a stint with Teach for America. Koch himself might have wound up a doctor—he sometimes supplements his paltry guiding income by working as a freelance masseuse—if he hadn’t been such a disaster in the classroom: “Hyperactive, the class clown, with ADD and all the rest of it,” he says.

When Koch was 12, his family moved to Denver, where he became a proficient mogul skier, and then on to Boston midway through high school. “The thing about my family is that we were just so conformist,” Koch says. “There was no model—not even any aunts or uncles—for living a different life.”

In 1987, fresh out of high school and with no particular plans for college, Koch bought a one-way plane ticket to Jackson, where the idea was to learn how to snowboard and to benefit from Wyoming’s legal drinking age of 19. He got a job baking cookies in Jackson Hole’s cafeteria, thus obtaining a season ski pass, and took a snowboarding lesson the first day the mountain was open. “That was it,” says Koch. “I picked it up instantly.”

“He was just a punk—a partying snowboarder,” recalls Tom Turiano, 36, a mountain guide who first got Koch interested in going off-piste. In June 1989, with just two seasons—but more than 200 days—of snowboarding under his belt, Koch set out to climb 13,770-foot Grand Teton with Turiano, hoping to become the first to snowboard it. “I had virtually no climbing experience,” Koch says. “I’d never roped up in the mountains before, and I barely knew how to self-arrest.” At first he lagged behind, tired and nervous. “When we got up on the east face,” he says, “I got a big second wind and took over breaking the trail. We started down and did two rappels in the Stettner Couloir, and I was like ÔWhy am I doing this? This is turnable terrain.’ I climbed back up and put the board back on.”

“After that, he was the shit,” Turiano recalls. “He was on the cover of both newspapers, everyone loved him, he made a lot of friends.”

That fall, Koch moved to Chamonix, France, curious to see the legendary valley surrounded by “the equivalent of 15 Grand Tetons,” as one Jackson climber put it. He washed dishes, modeled skiwear for a Swedish photographer, bought a valley ski pass, and found an Aussie girlfriend. “Chamonix was the sixties for me,” he says. In terms of mountaineering, it was grad school. Koch saw the exploits of his French counterparts—legendary extremistes like Bruno Gouvy, Jean-Marc Boivin, and Patrick Vallencant—up close and did several climbs with another French standout, snowboarder Alain Moroni. “I realized that a lot of people in Chamonix were making a living doing this stuff,” Koch says. “They were known to the general public; they were in the press. I was like ‘OK, it’s possible to make this happen.’ ”

“I remember going into a bar with Stephen and watching this film of Gouvy jumping off a helicopter onto the tip of the Dru, snowboarding it, and then breaking out his paraglider and flying down to the valley,” recalls Greg Von Doersten, 39, a Jackson photographer who visited Koch in Chamonix. “It was superhero stuff—that whole idea of enchainement, of hopping off one thing and flying to the next. If you saw that and you were young and ambitious, you had to say, ‘Wow, the possibilities are limitless.’ ”

As long as you stayed alive. While snowboarding alone, Koch had several very close calls. Then one day he heard that the great Gouvy himself, clad in his skintight Marlboro speed suit, had hopped out of a helicopter atop the Aiguille Verte, taken a couple of crisp practice turns above the Whymper Couloir, and promptly lost his edge and tumbled 3,000 feet to his death.

“Gouvy once said something about the grass being greener, the sky bluer, after one of these descents,” says Von Doersten. “But you looked at him and you had to think, ÔOK, but you also started this machine that you couldn’t stop.’ ”

KOCH LEFT CHAMONIX in the fall of 1990 and, except for one glamorous hiatus, has lived in Jackson ever since. His current residence is a two-story condominium on a quiet street corner, equidistant from the brew pub and Snow King, the local ski hill. It’s a comfortable place, but he doesn’t own it; unlike many of his contemporaries, he missed out on the real estate boom of the early and mid-nineties. Though he professes to be happy with the mountain-bachelor lifestyle—a dependable 18-year-old Toyota pickup, a garage stacked with gear, a few bottles of wine in the rack—he’s always looking for the next big opportunity.

In 1995, one of Koch’s Exum clients offered to introduce him to Jann Wenner, the publisher of Rolling Stone and Men’s Journal, who was vacationing in Sun Valley, Idaho. “He went up there and hung out with Jann for the weekend,” says Wade McKoy, who has been on four of Koch’s Seven Summits expeditions, “and the next thing you know, Men’s Journal is helping pay for our Denali trip.”

With the Alaska trip scheduled for June 1996, Koch went off to Nepal that spring on a wildly audacious project: a climb of 27,923-foot Lhotse, Everest’s slightly shorter but much steeper neighbor. Since Lhotse shares a base camp with Everest, Koch brought his snowboard, thinking that if things went well, he might sneak onto Everest sans permit and “poach” a first descent.

His first day in camp, a teammate introduced him to New York-based climber Sandy Hill Pittman, who had recently separated from her husband, media executive Robert Pittman. (They divorced in 1997.) She was there to climb Everest with a guided group from Mountain Madness. The two had spoken previously on the phone—Koch had called Pittman, who was pursuing her own Seven Summits quest, for logistical information—but this was their first face-to-face meeting. They got to know each other as part of a group of climbers bonding over a bottle of Jack Daniels, Koch recalls, and subsequently began a romantic relationship.

It was a relationship that was soon overshadowed, first by the events of May 10, 1996, when eight Everest climbers and guides perished—including Scott Fischer, the guide for Mountain Madness—and then by the controversies and recrimination that followed. In Into Thin Air, Jon Krakauer’s chronicle of the Everest disaster, Pittman is introduced as “a millionaire socialite-cum-climber” and a “shameless” publicity seeker. “Fairly or unfairly,” Krakauer wrote, “to her derogators, Pittman epitomized all that was reprehensible about [the] popularization of the Seven Summits and the ensuing debasement of the world’s highest mountain.” To Koch, the criticism of Pittman was unfair and disproportionate—”as if she invented the idea of guided climbing,” he says scornfully.

On Lhotse, Koch made it to nearly 26,000 feet—Camp 4—before being stopped by exhaustion and dehydration. He was descending the mountain when the big storm hit Everest. Once back in the United States, he escaped to Mount McKinley to collect the third of his snowboarding summits. Afterward, Pittman invited him to New York to be her houseguest, and Koch wound up staying more than a year and a half.

“Stephen offered me tremendous support after 1996,” Hill, who has since remarried and now goes by her maiden name, wrote me in an e-mail. “He had been there, and he knew what had really happened and that so much of what was written following was exaggerated and fabricated to sell books, magazines, and movies.”

One of Koch’s reasons for moving to New York was to find backing for his Seven Summits Snowboarding Quest, but his efforts failed to produce the funding he sought. “If all the media frenzy of 1996 hadn’t happened, he probably would’ve found sponsors for his Everest trip then,” Hill wrote in her e-mail, “but I remember people telling him, ÔOh, Everest—that’s an old story already . . . everyone’s doing it now,’ as though what Stephen had in mind could be pulled off by some weekend snowboarding teenager.”

Nevertheless, Koch stayed in New York, telling himself a gym was a gym—he could train for big peaks anywhere. In the climbing world he became known as “someone who can hang in high society,” as he puts it. But he did pull off one successful expedition during his New York sojourn: In January 1997, he, Wade McKoy, and climber Scott Backes went to Kilimanjaro to attempt the highly technical Hein Glacier route. “I was in the best shape ever,” Koch says. “We did a new ice route on the way up and just killed it.” Not long afterward, Koch’s relationship with Hill ended, and he returned to Wyoming.

Back in Jackson, Koch began focusing on another long-dreamed-of objective, the Northeast Snowfields of 12,922-foot Mount Owen in Grand Teton National Park. Early one morning in April 1998, he made his bid. “It’s a beautiful big face and a gorgeous line, and that’s really all I was thinking about,” he says. “I didn’t have a turnaround time, didn’t realize how warm a day it was—I had blinders on.” Koch heard the roar of the avalanche a few seconds before it hit him, but there was nowhere to shelter. It swept him some 2,000 vertical feet, hurtling him over several cliff bands, breaking his back, lacerating his liver, tearing the ligaments in one knee and completely dislocating the other. Miraculously, he wasn’t buried. Sliding on one hip, his other leg flopping uselessly, he worked his way downhill to a relatively secure spot, then spent the night waiting for rescue in his warmest garment—a long underwear top. A friend alerted park rangers that Koch was missing, but it wasn’t until the next morning, 23 hours after his accident, that a rescue helicopter found him.

Being Sandy Hill’s boyfriend hadn’t helped Koch’s credibility in the mountaineering world. The accident on Mount Owen seemed to confirm his dilettantism. “It led to a lot of skepticism about Stephen in the local climbing community,” recalls Angus Thuermer, a climber and the editor of Jackson Hole News at the time. “It was a pretty elementary mistake. But I’ll say this: I’m not sure anybody else would have survived.”

IT’S 5:30 IN THE MORNING, and the floor of Koch’s otherwise tidy living room is a sea of gear: ropes, slings of climbing hardware, axes and crampons, headlamps, batteries, and little packets of Gu. Five minutes later, it has all disappeared into a small daypack. Fifteen minutes after that, having heaved a snowmobile into the back of a friend’s pickup truck, we’re rolling west out of Jackson toward Teton Pass and the Idaho state line.

Koch had ligament surgery in October, his fourth procedure on the right knee and his sixth overall—the lingering legacy of Mount Owen. Today, nine weeks later, is a big test: his first day of ice climbing. Koch’s knee is still volleyball-sized, but if he’s worried, he doesn’t show it. “Check this out,” he says, grabbing his lower leg and pulling back on it. It travels a good inch rearward in the socket before stopping with an alarming clunk. “That’s the PCL, the posterior cruciate ligament. Not really there anymore. But this way”—he pushes his leg side to side—”this is what I care about, and it’s pretty good.”

When Koch talks about Mount Owen, he tends to emphasize the positive. The accident, he says, was a “giant wake-up call” that set him on a new path. “Too much to do,” he told the Jackson Hole News from his hospital bed a week after the accident. “People to love. Babies to have. It’s a sign I’ve got more work to do on this earth—helping others, especially, since I’ve been helped so much.”

Spend some time with Koch, however, and you begin to suspect that the opposite is true—that his life hasn’t changed at all. On the expedition to Peru, in 1999, we’d teased Koch for what he called his “homework”: a book his first serious girlfriend since Hill, Tina Flowers, had given him, called Getting the Love You Want. Koch dutifully read it, and on his return to Jackson even got engaged to Flowers, an athletic, outgoing woman with a successful housecleaning and housesitting business. Then things fell apart. “I don’t really know why,” Koch says. He sighs, then hastens to smooth things over. “But it’s good. We’re still friends.”

“Basically, it was a major decision to go with his career over wife and family,” says Tom Turiano. “But deep down he wants a family, and he knows he blew it with Tina.”

If Koch has found any comfort since Mount Owen, it’s been in his climbing—a sport he’s approached in a different way from his snowboarding. In Peru, the team was shocked and dismayed when Koch quit the expedition before we had even approached our main objective, a ski and snowboard descent of the West Rib of Huascaran—an act that, at the time, seemed monumentally selfish. But in retrospect, Koch’s lame-sounding explanation—”I just want to swing ’em,” he said, miming the action of his ice axes, “and not carry the board all over the place”—may well have been genuine. Over the years, and in between his Seven Summits expeditions, he’s racked up a fairly impressive list of ascents, most notably the last of the three Alaska routes he did with Marko Prezelj—a 48-hour, nonstop push up an unclimbed rib on the southwest face of Mount McKinley.

“I think Stephen has made a natural evolution to alpinism, to making the full commitment,” says Jack Tackle. “I’d like to see him evolve to the point where he could just decide what’s important to him. My sense is, it’s not snowboarding.”

FROM THE TETON CANYON trailhead, it’s about three miles to the ice formations Koch wants to climb. They don’t look too hairy at first, just some ragged drips coming over the edge of a small cliff band. But 20 minutes later, standing right under them, they’re suddenly formidable: thin sheets of dimpled ice hanging from the rock like crumpled paper.

As the rest of us—a local dentist and a civil engineer, both bike-racing pals of Koch, and I—slowly gear up, our leader stamps his feet in excitement. “The ice is perfect—so gooey,” he says. “This is gonna be so cool.” It’s all Koch can do to contain himself—and a minute later, he can’t. “God, I love myself!” he yells.

Everybody laughs. Where did that come from? But it’s classic Koch—narcissistic, perhaps, but also totally unpredictable, and refreshingly incorrect.

Moving powerfully, Koch levers his way up the biggest piece of ice, then turns his attention to a problem that looks truly “interesting”: a fanglike frozen waterfall 30 feet high that tapers to a column no thicker than his own thigh. Later, he tries another, trickier approach, via an overhanging shelf of rock and ice. He’s halfway across, hanging tenuously by one arm, when a suitcase-size chunk of ice collapses onto his shoulder. It’s an Incredible Hulk sort of moment—only a sudden burst of inhuman power is going to keep him from falling. Koch sends a bellowed obscenity ringing across the canyon, shrugs off the ice block, and then swings his free arm high overhead, hoping for a good stick. He gets it and, with one more shout, pulls himself over the lip.

“Well, that was exciting,” he says, his voice calm again.

All things considered, it’s a good first day back. “The knee is good,” Koch says as we get into the truck for the drive back to Jackson. “I think I can start getting back on the snowboard.”

Still, it’s a long way from Teton Canyon to the North Face of Everest. The immediate issue is money. “We don’t have the cash to foot the bill for an Everest trip, and I don’t think any other companies in the industry do either,” says Scott Hinton of Petzl, one of Koch’s main gear suppliers. “I think he’ll either have to do this really cheaply, which basically means on his own, or get some big sponsor, like a Red Bull, a Pepsi, or an MSN, which means sat phones and that crazy stuff.”

But when I see Koch in New York in early February, he insists he’s not worried about sponsors. He’s in town to talk to agents and film producers. The amount of money being discussed, Koch says, makes his original $180,000 budget (for a team of four climbers and two cameramen) seem almost laughably unambitious. ” ‘I can get you $250,000 for the trip right now, and another $750,000 for post-production,'” Koch says one producer told him.

Apart from financing, there is one other obstacle: the Hornbein itself. “It’s very hard to find the right conditions,” says Dominique Perret, a Swiss freeskier who, along with Swiss snowboard mountaineer Jean Troillet, tried to climb and ski the couloir in 1996 and hopes to return for another bid in 2004. “The monsoon is an unsettled time when there are a lot of systems coming through. After a storm, you need a day of good weather for the mountain to clear itself—for the loose snow to slide off—and then two more days to make the climb, at least.”

Koch has never been above 26,000 feet, which he reached on Lhotse. He also has a history of poor circulation in his toes—an annoyance on most mountains but a potentially lethal handicap for an Everest snowboarder. And then there’s the sheer drudgery of postholing up 10,000 vertical feet. “Technical climbing is always interesting, because you’re trying to find the route,” says Prezelj. “But this is just snow. You need a very strong motivation.”

So what is Koch’s motivation? Ask him and he shrugs. “It’s just the line, man,” he says. “Any skier will tell you that—the best line on the highest mountain in the world.” OK, but why all the added hurdles—no oxygen, no Sherpas, the insistence on a one-push alpine-style ascent? Tellingly, the answer is a climber’s, not a snowboarder’s. “Because style matters,” Koch says. “Most people never think about style on Everest, but they should.”

It’s a pretty good clue to how Koch has wound up in the delicate position he’s in. A wiser head, of course, might simply abandon the project. (Nearing the end of his own famous quest, Ed Viesturs, the American mountaineer who has successfully climbed 12 of the world’s 14 8,000-meter peaks, continues to maintain he’d rather be careful than triumphant.) But sitting on a friend’s couch in New York, Koch doesn’t want to hear about Viesturs or anybody else with the courage to walk away from his dream.

“Listen,” he says, sinking back in his seat, “I just want to do this, and then I wanna be free.” He takes a deep breath. “I can’t wait to be free.”