Sometime this spring, Chris Davenport—ski mountaineer, film star, perpetual-motion machine—will ski up and then down , a 13,838-foot summit in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains of south-central Colorado. The outing will wrap up an extraordinary nine-year project: tackling the Colorado Centennials, the 100 tallest peaks in the state, with fellow skiers Ted and Christy Mahon. If that doesn’t mean much to you, consider that the project has entailed hiking, climbing, and skiing some 350,000 vertical feet—roughly the equivalent of 28 round trips from Everest Base Camp to the summit. (Davenport also skied the Lhotse Face of Mount Everest in 2011.)��

“I used to think I was the hardest-working guy in the ski industry, until I started spending time with Dav,” says Mike Douglas, a professional skier and filmmaker.��

Davenport has parlayed his boundless energy into one of the most successful careers in the adventure game. But during his 20-year run, most of his accomplishments have been little known outside the skiing community. He’s won an in ski cross; gained generous sponsorships from Kästle, Red Bull, Scarpa, and Spyder; and skied on every continent, including pioneering descents in Antarctica and Norway. Last November, he was inducted into the for being one of the “world’s premier big-mountain skiers.” He’s also built a successful ski-guiding business, run summer ski camps in South America, authored two books on ski mountaineering, helped Scarpa develop a new boot, hosted a show on ���ϳԹ��� Television, sat on the board of (a snow-sports coalition that fights climate change), and raised three boys (Stian, Topher, and Archer) with his wife, Jesse, a ski patroller in Aspen, Colorado.��

Davenport’s career took off in 1996, when he won the World Extreme Skiing Championships in Alaska. By the early aughts, he was starring in ski-porn installments from and . But by 2005, the youthful bravado that allowed him to stomp landings off 50-foot cliffs began to fade, even as his desire to ski big mountains continued to grow.��

“I’d become a little jaded with filming,” says Davenport. “I felt like I’d achieved a lot of my goals by that point, and I was looking for something fresh.”

In the fall of 2005, he had an idea: he would ski all the fourteeners in a single year.

“When I told Jesse, she was like, ‘Are you fucking kidding?’ ” says Davenport. “I think she was hoping I might dial things back.” The two had just started a family—Stian was born in 2001 and Topher in 2003. “But I still felt really strong, and I wanted to do something new and big and different.”��

At the time, the skiing industry was shifting from a focus on conventional alpine skiing toward off-piste, human-powered adventure. Davenport’s fourteeners project was one of the first to build on that momentum.

“Only one person”—Colorado native Lou Dawson—“had skied all the fourteeners,” says Davenport. “Skiing them in a single year seemed like a really great opportunity.” He set out on January 22, 2006 and finished the -final, 54th peak on January 19, 2007. “It was probably the best year I’ve ever had,” Davenport says. “It reignited my passion for the mountains.”��

Recharged, Davenport ticked off other big peaks on his bucket list—Denali, Everest. In 2012, he was driving around the Pacific Northwest in an RV, skiing Cascade Range volcanoes with Ted Mahon, a pro skier, and Christy Mahon, director of an Aspen environmental organization, when they decided to tackle the Centennials. “We were fit and��strong, and we wanted to push the bar higher,” says Davenport. “By the end of the trip, we were set on doing it.”

By 2005, the youthful bravado that allowed Davenport to stomp landings off 50-foot cliffs began to fade, even as his desire to ski big mountains continued to grow.

The Centennials, if a touch shorter than the fourteeners, aren’t any easier. Several have required multiple attempts due to weather and snow conditions. Of the five that remain on the list, three—Jagged Mountain, Pigeon Peak, and Turret Peak—are among the most remote in Colorado, requiring another trip into the Weminuche Wilderness on the Durango and Silverton train, followed by an eight-mile approach on foot and climbing skins. (For an account of the group’s first Weminuche mission, see “The Hundred-Mountain Siege,” below.) Weather permitting, an alpine-style assault on the summits could get them done in a day or two, but as Davenport notes: “Everything has to go perfectly.”

Davenport knows that things don’t always go as planned in the mountains, though somehow he has managed to avoid serious injury and encountered nary an avalanche during the project. In 2006, on 14,011-foot Mount of the Holy Cross, while he and some other skiers were headed uphill, Davenport stopped to take a photo when someone yelled “Rock!” He looked up just in time to sidestep a watermelon-size boulder that came whistling down a couloir. Another time, on Vermilion Peak, he leaped off a cornice into a steep, frozen chute and fell onto his back. He managed to spring up just before hurtling hundreds of feet down the slope.��

“The joke is that Davenport has a golden horseshoe up his butt,” says Douglas. “How do you ski all the fourteeners in a year, in some of the sketchiest snowpack in the country, and not have a single avalanche?”��

As this story went to press, the five remaining Centennials were being pounded by powerful winter storms, setting Davenport and the Mahons up for a May sojourn. Which raises the question: What’s next?

“I’m not sure yet,” he says. “I’m kind of hoping to take Stian up the last peak. He’s starting high school this year, and this could be the metaphorical passing of the torch. I’m 44, but I feel 34. As an athlete, you get this question all the time: How far can you go? What is the age cutoff? I’m still curious about my potential.”

The Hundred-Mountain Siege

The Centennial Peaks project is one hell of an accomplishment. Here’s a closer look at what went into the effort. —

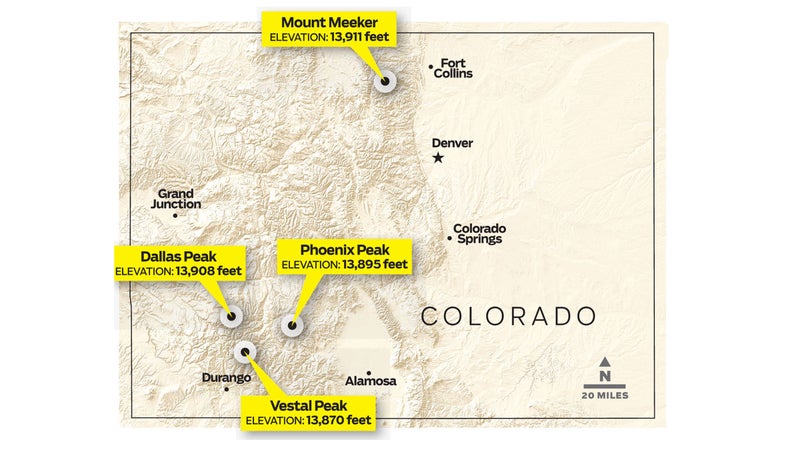

Phoenix Peak

May 19, 2014

“We weren’t too excited to ski it: there wasn’t much snow when we made the ascent, the wind was relentless, and the mountain looked like it lacked any great ski objectives. But getting to the top we scouted a steep, east-facing bowl and ended up dropping some super fun lines.”—Christy Mahon

Vestal Peak

May 9, 2014

“Accessing the Weminuche peaks requires a trip on an old steam locomotive, and during spring ski season it runs only once a day. At the end of our five-day traverse, we had to climb and ski one of the most challenging peaks of the project, Vestal, and then break camp and make it six miles out to catch the train home. From the moment we awoke we had to hustle. We were running down the dry trail with our skis and boots mounted on our overloaded packs.” —Ted Mahon

Dallas Peak

May 1, 2014

“This was some of the most challenging alpine climbing I’ve ever done. We don’t normally expect steep snow, little ice, and a narrow rock chimney in the Centennials, but Dallas is different. The rappel from the summit back to our skis was easy in comparison—and the descent was totally sublime.”��—Chris Davenport

Mount Meeker

May 11, 2013

“What we found on the south face of Meeker after we summited blew our minds: 2,000 feet of epic powder and perfect spring corn. It was one of our more thrilling descents.” —Chris Davenport

Meet the Team

Chris Davenport

Age: 44 ��

Project Highlights: Thunder Pyramid, Dallas Peak, Rio Grande Pyramid

Because: They were the most physically and mentally demanding.

Also Known For: Wildly unsuccessful attempts to find north-facing routes down the Centennials.

Christy Mahon

Age: 39��

Project Highlights: Ice Mountain, North Apostle

Because: The Refrigerator Couloir on Ice Mountain is legendary, and North Apostle is an easy ski with great views.

Also Known For: Total contempt for Gu Shots.

Ted Mahon

Age: 42��

Project Highlight: Vestal Peak

Because: It’s an iconic Colorado mountain, and it was such a massive effort to haul ass out of there to catch the 2 P.M. train home.��

Also Known For: Calling out the name of every peak, subpeak, foothill, and stream while on missions.��

How the team’s vertical gain compares with other high-altitude endeavors

350,000 feet: Elevation gained during the Centennials project

128,100 feet: Height of Felix Baumgartner’s Stratos jump

39,000 feet: Cruising altitude for a commercial jetliner

29,035 feet: Mount Everest