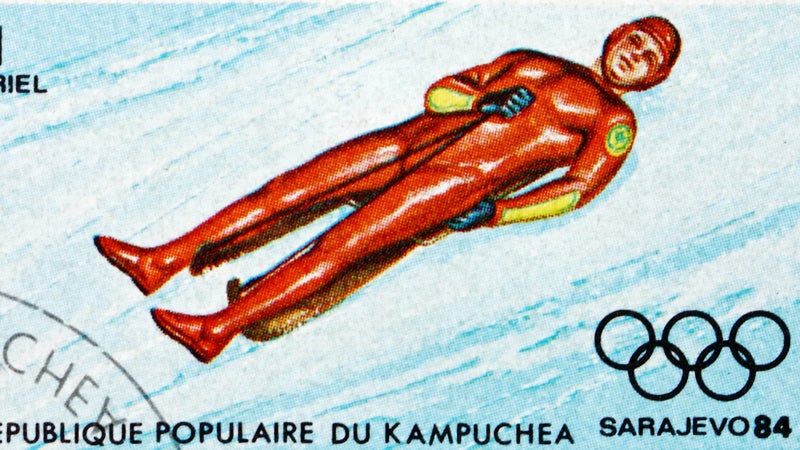

Long before the Jamaican bobsled team’s recent resurgence in popularity, George Tucker, a 37-year-old doctoral student in physics, became the first Winter Olympian from the Caribbean. Representing Puerto Rico in the luge, Tucker bumped down an icy track in the 1984 Sarajevo Games, where he finished dead last. Despite his disappointing run, he quickly became a press favorite—and an inspiration to athletes in other tropical nations.

A tower in Sarajevo displays the logo of the XIV Olympic Winter Games.

A tower in Sarajevo displays the logo of the XIV Olympic Winter Games. George Tucker with a friend in December 1984.

George Tucker with a friend in December 1984. Tucker and his wife at Sossusvlei Desert Lodge Observatory in Namibia.

Tucker and his wife at Sossusvlei Desert Lodge Observatory in Namibia.Tucker was “the one who set the competitive standards for Caribbean nations,” luging coach Rich Kolko told The New York Times in 1992. Kolko’s right: soon after Tucker’s appearance in 1984, lugers from Puerto Rico, Brazil, Venezuela, the Virgin Islands, and, yes, Jamaica began to show up. (The bobsled team that inspired Cool Runnings, the 1993 Disney movie, was assembled after George Fitch, one of its founders, saw Tucker compete.)

To understand how Tucker found himself lying faceup on a sled in Yugoslavia, we must go back to when he was a young child, living with his parents—who both worked for the distribution arm of RKO Pictures—in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Tucker’s mother never forgot his early fascination with the stars there, a passion that continued after the family moved to the U.S. when her son was four years old. “We had a great sky; you could see the Milky Way,” Tucker says of the small town in upstate New York where he spent the bulk of his childhood.

As a teenager, Tucker taught himself and others about stargazing, light pollution, astrophotography, and physics. The future Olympian didn’t give much thought to athletics until, while an undergraduate, he became “reasonably good” at basketball. He was watching on July 20, when Puerto Rico’s Olympic basketball team caused a stir at the 1976 Summer Games in Montreal. Playing against the previously undefeated United States, the Puerto Rico team nearly managed a major upset. The U.S. got by with a razor-thin win of 95–94 after a buzzer shot by Puerto Rico was discounted. Credit for that shot, and for another 35 points during that game, belonged to a player named Alfred “Butch” Lee Jr.

Like Tucker, Lee had grown up mostly in the state of New York, after having been born in Puerto Rico to American parents. When his coach at Marquette University didn’t choose him for the U.S. Olympic basketball team, Lee discovered he could play for Puerto Rico instead. “Up until then, I’d never thought about Puerto Rico and the Olympics because I thought, well, I live in the U.S.,” Tucker says. “So I kept that in the back of my mind.” Years after moving away from San Juan, the place still meant something to him. “I had posters on my wall from Puerto Rico. I was born there, so I considered myself Puerto Rican,” he explains.

Four years later, Tucker was living in Albany when the 1980 Winter Olympics came to Lake Placid, just two hours away. Tucker and a group of friends made the drive up to watch athletes at the training site. At the luge track, they saw a competitor practice. At the start of a single luge race, a luger sits on a small sled and grasps a horizontal bar on either side of the track. He uses the bar to slide back and forth, building up momentum before launching himself down the track.

As Tucker and his friends watched, the Olympian stood, placed his hands by his knees, and jumped off the ground as if simulating a launch. “Well, he jumped a couple of times, then he came down and landed on the ice, and smashed his head on the ground,” Tucker says. “A friend turned to me and said, ‘Now �ٳ�����’s the sport for you.’” Tucker brushed it off. Another three years would pass before an Olympic thought crossed his mind.

Tucker is quick to point out that, while his participation in the Olympics probably amounted to his only 15 minutes of fame, that’s really only a minor part of his life. But what got him to Yugoslavia—some combination of a why-not attitude, a fondness for the underdog, sheer recklessness, and serendipity—also played a role in his academic pursuits. Though Tucker earned his first doctorate in astronomy, after learning there were few jobs for astronomers in the U.S., he went back to school for physics. For most of his life, astronomy was just a hobby. Then, as he grew older and watched his favorite childhood stargazing sites become lackluster with light-polluting development projects, he knew something had to change.

“It’s hard to rally the troops about light pollution because it’s such an incremental process,” Tucker says. “But, every day, year after year, it’s going to get worse and worse. As a kid, I was so thrilled to see the big Milky Way, and to realize that such views are going to vanish from most of the world is pretty depressing.” In 2003 Tucker traveled to Namibia, where he photographed the night sky as part of a passion project, hoping to get the NamibRand Nature Reserve certified as a dark sky site under the International Dark Sky Association (IDA). That designation would mean that the park would keep light polluting fixtures to a minimum and attract stargazing tourists.

Tucker helped fill out a 100-plus-page application, took inventories of existing light fixtures, and photographed the night sky. NamibRand got its certification as an International Dark Sky Site last year, and Tucker now has his sights set on locales in the Galapagos and Southern Africa. The thing about these sites, Tucker says, is that �ٳ���’r�� not places the IDA usually recognizes for certification. The organization has overwhelmingly awarded dark sky status to sites in cities, or areas that are already quite developed and not nearly as dark as NamibRand.

“It’s kind of a lonely battle at the moment,” he says. Listening to Tucker, it’s hard not to think back to his Olympic experience, when he found himself in a new place, bringing an underrepresented country to the Winter Olympics—and all without much support. In both scenarios, you have to give him credit for really sticking with it.

Which brings us back to the spring of 1983. Tucker was pursuing his Ph.D. in physics at Wesleyan University, using a new technology called the tunable diode laser to measure the oxygen isotope ratios in nitrous oxide. As the 1984 Winter Olympics approached, Tucker thought back to the training site at Lake Placid. He decided to buy a $25 membership to the United States Luge Association, which would allow him access to training sessions at the track. Then he’d buy his buddies memberships as Christmas gifts so he could get revenge for some disastrous ski trips they’d taken him on. “I always got hurt,” he says. “It was the one time of the year I’d ski. So I had this evil plan: ��’m gonna take them up, and �ٳ���’r�� gonna get hurt. And, this time, ��’m gonna stand there and laugh.”

Tucker next wrote to Puerto Rico’s Olympic committee, asking if he could qualify for the island’s Winter Olympics team if he became proficient enough at luge. “It was just for grins,” he says. “It was more to get the letter rejecting me.” During Tucker’s first training session at the Lake Placid Olympic Sports Complex, he watched his fellow amateur lugers clumsily bang off the walls and decided they were oversteering. So he let his sled run mostly straight, and “got going really fast,” he says. But he still crashed—in three out of five runs—watching as his peers improved enough to luge from farther up the track. “I got left behind,” Tucker remembers. “It was like I failed the class.” Nevertheless, he signed up for a weeklong training camp in March. But, when the time came, warm weather melted the track, and the event was canceled.

Around that same time, a letter arrived from Puerto Rico. “My rejection letter, right?” Tucker deadpans. “I open the envelope, and it says, ‘Wonderful news, you are entered to compete in the 1984 Winter Olympics in Sarajevo. You will be the first Puerto Rican Winter Olympian.’” After a long what-the-hell-do-I-do-now moment, Tucker decided to follow through. There was still a chance, he thought, that he could become proficient enough at luge to qualify after all. The timing was perfect. His thesis was wrapping up, but because he was still waiting on lab results, he wouldn’t be able to get his Ph.D. until the following year. He had time to kill.

That December, Tucker went to train in Lake Placid, battering himself around on what he describes as “the worst, most dangerous track in the world.” Unlike athletes on the U.S. team, Tucker didn’t have access to protective gear like arm pads. His tendency to gash up his arms on the sides of the track quickly earned him a nickname: the Luger Who Dripped Blood. “I’d take maybe four or five runs a day,” Tucker says. “Every run I could get.” But then, at the end of the month, the track closed to everyone except U.S. Olympic athletes. Tucker knew he wouldn’t qualify with only two weeks of training under his belt, so he went to the Luge Association’s office to turn in his equipment for good.

Just as he was about to walk out of the office, another man entered. He’d seen Tucker around, and asked him what he was doing at the track. When Tucker explained that he’d wanted to represent Puerto Rico in the Olympics, the man said, “Come with me.” He was the president of U.S. Luge, and he was upset that no one had told him about Tucker (at the time, luge didn’t have the required minimum number of countries to compete in the Games and was perilously close to losing its place in them). “It’s really vital that you compete,” he told Tucker. Less than a month later, with special permission from U.S. Luge, Tucker arrived in Sarajevo early to train with the Yugoslavian Olympic luge team.

All it took was one quick chat with a reporter for Tucker to become something of a press darling. He didn’t pay much attention to the coverage—Sports Illustrated described him as “the press’s favorite loser … an overweight but quick-witted doctoral student”—but he was getting plenty of it. In the U.S., he figured even more prominently than Paul Hildgartner, the Italian luger who ended up taking gold in the event.

“Trust me, I wasn’t looking for publicity,” Tucker says. “I thought it was going to end up with me splattered all over the track, so the less publicity beforehand, the better off I figured I was. I didn’t want to embarrass Puerto Rico—that was the big thing.” And then, 14 practice runs, several qualifying rounds, and a couple of actual runs later, it was over. Tucker finished 30 out of 30 (though, he points out, it was technically 30 out of 32 because two competitors crashed and were disqualified).

Just eight years later, much of Sarajevo would be destroyed during the Bosnian War. “At the time, I thought that I’d go back there someday and see all these people I’d befriended,” Tucker says. He speaks highly of his fellow lugers, having spent a lot of time with the Yugoslavian Olympians. “When you saw them all together at parties and stuff, they were wonderful,” he says. “But then it all fell apart.” Some of the Yugoslavian athletes he met have died since the war, and he’s not sure he’s ready to go back.

These days, Tucker keeps his Olympic memorabilia—sleds included—in his garage. He doesn’t talk about that time much anymore, although he did pave the way for Caribbean athletes hoping to compete in the Winter Games. “There were Puerto Rican athletes who approached me with questions about how they could represent the country,” Tucker says. “I helped about fifteen of them get started in different winter sports, and several did make it to the Olympics.” In fact, when Tucker returned to luge at the 1988 Winter Olympics in Calgary, he competed alongside Raúl Muñiz, a 31-year-old New Yorker whose parents were born in Puerto Rico. Tucker had convinced Muñiz to try luging when they bumped into each other at Lake Placid in 1984.

The Calgary Games saw another tropical team make its debut, thanks in part to Tucker’s influence. The Jamaican bobsled squad didn’t officially finish in its first stint at the Olympics. But they were crowd favorites—and, like Tucker, true underdogs—going on to qualify for every Winter Olympics through 2002. And participation among tropical nations in the Winter Olympics has been steadily growing ever since, with 16 such countries competing in the 2014 Sochi Games.