In 2013, 15-year-old Dawson Toth was perched on a ridge watching his best friend, Evan, ski down the north slope of Hero’s Knob, a popular backcountry area in Kananaskis County, Alberta, when he saw the avalanche. “It started at my ski tips,” he recalls. “Then I watched the slide spread across the whole slope.”

The wall of snow engulfed Evan, then both teens’ fathers, who were waiting farther downhill. Once the slide petered out, Dawson jumped off the crown onto the now bare shale below, switched his beacon to search mode, and made his way toward the buried victims. “There wasn’t much going on in my head except that I needed to find my friends and family fast.”

Luckily, three years earlier Dawson had received training from a guide certified by for just this sort of scenario. Within a minute he’d dug out Evan’s dad, whose hand was protruding from the softly packed snow near the top of the slide. Thirty feet down, he saw his own father buried to the waist. But where was Evan? Dawson worked downslope in a grid pattern, and soon his beacon homed in on another signal. When his snow probe struck something roughly five feet below, he and a few helpers who’d come upon the scene began digging frantically. Evan was unresponsive when Dawson pulled him from the debris. But as soon as Dawson cleared the snow from Evan’s mouth, his friend coughed and inhaled rapidly.

Relatively few teens in North America die in avalanches each year, but increasing numbers of young rippers are likely to head for the backcountry—and into harm’s way. Many guides and educators are pushing for earlier avalanche instruction so that if things go wrong, as they did for Dawson and Evan, teenagers will have the skills to deal with it.

“I liken it to sex education,” says Mary Clayton, a former ski guide and communications director for Avalanche Canada, whose 16-year-old son, Aleks, has started venturing out of bounds. “I know it’s going to happen, so I won’t put my head in the sand.”

Seniors at public high schools in Jackson, Wyoming, take a ten-day snow-safety course as part of the science curriculum; by adding a two-day field session, as dozens of students did during the 2016–17 school year, they can earn Level 1 certification, the first of two levels of recreational avalanche education. High schools in Breckenridge, Crested Butte, and Vail, Colorado, also offer snow-safety courses. And Avalanche Canada launched a youth-focused avalanche-awareness program in 2005 that reached nearly 8,200 kids across western Canada last year alone, some as young as six.

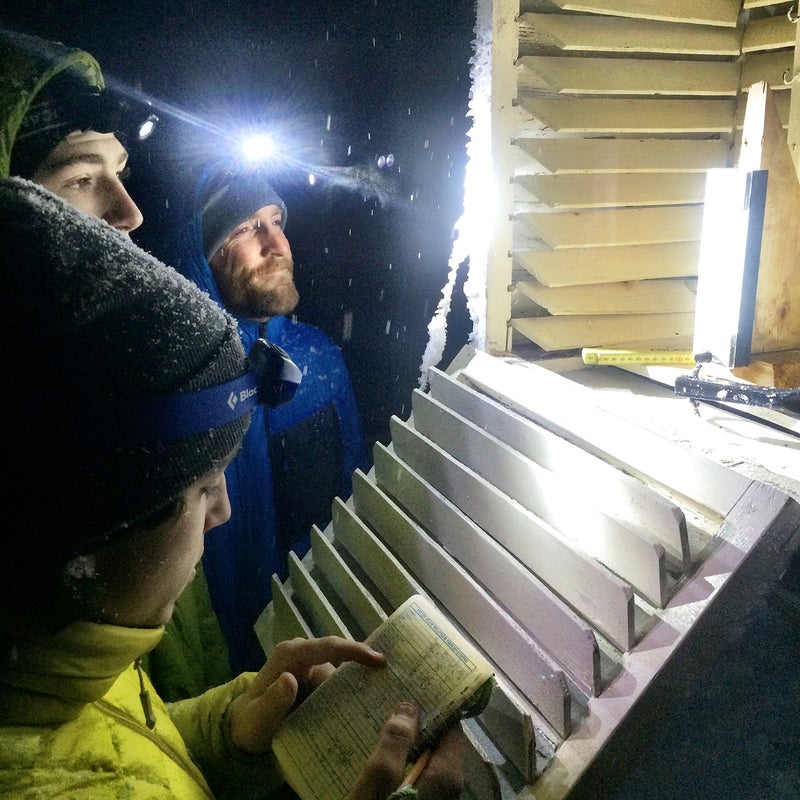

High schoolers who want to earn safety certification go through the same steps as adults: learning basic snow science, digging snow pits, performing stability assessments, using transceivers, and practicing rescue scenarios. In basic awareness classes, elementary school kids may learn some of those skills, too, or stick with things like identifying avalanche terrain. In Jackson, the youngest participants focus on abstinence, says Sarah Carpenter, co-owner of the American Avalanche Institute: “As in, ‘Here’s why you never leave the resort gate without an adult who is prepared.’”

We know avalanche education works, says Jordy Hendrikx, who directs the Snow and Avalanche Laboratory at Montana State University. According to data from the , the number of fatalities remained essentially flat between 1995 and 2016, despite an explosion in backcountry use among skiers, snowboarders, and snowmobilers. But the educators and snow scientists I spoke with expressed concerns about whether a little bit of avalanche education will push young people—who tend to have high risk tolerance and an eagerness to impress their friends—to go further than they would otherwise.

“Are we enabling people to increase their exposure but also decrease their risk?” Hendrikx asks. Carpenter wonders the same thing: “A lot of high school kids are ducking the rope, building a jump, and sessioning it for hours. So we tell them, ‘Here are the places you want to avoid putting your jump.’ Do I want them to take those same skills and go big-mountain skiing without supervision? No.”

Hendrikx, who in recent years shifted his focus from snow science to how decisions are made in the backcountry, is conducting a study with colleagues from Sweden and Norway to better understand the role that status plays in peer groups, including kids who’ve grown up with exposure to off-piste powder shots via social media.

What they might find, at least among some teenagers, is that the tide of social stigma has actually begun to turn against cavalier attitudes. “People used to not think twice about ducking the rope,” says Andreas Massitti, an 18-year-old from Canmore, Alberta, who started competing in big-mountain freeskiing competitions when he was 14—the same year he took an avalanche course. “Now, with kids my age and younger, if you go out there without the gear or on a bad day, it’s like, ‘What were you thinking?’ People give you heck about it, eh?”

Youth Avalanche Safety Courses Near You

Parents: Keep your rippers safe in the backcountry with these youth-specific avalanche-safety courses. Don’t see one near you? Contact the snow-safety nonprofit to request a free presentation by an avalanche expert. —Nicholas Hunt

Alpine Skills International

Tioga Pass, California

A five-day touring and mountaineering course for 12-to-18-year-old skiers that covers everything from packing techniques to risk assessment. Late spring; $925;

Utah Mountain ���ϳԹ���s

Salt Lake City, Utah

Students 13 and up who take this three-day course, which combines classroom lectures and field sessions, walk away with American Avalanche Association Level 1 certification. December 27–29; $349;

Selkirk Outdoor Leadership and Education

Sandpoint, Idaho

Anyone 16 and older can sign up for SOLE’s avalanche courses, but it offers a Level 1 course designed expressly for 16-to-25-year-olds.January 13–15; $345;

CAPOW Canadian Powder Guiding

Revelstoke, British Columbia

How to be a Young Person that Older People Respect is a camp focused on the skills, knowledge and respect needed to safely navigate avalanche terrain. Ages 15 and up. December 19-23; $1498 (CAD);