On October 9, the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race announced that several dogs on a single team had for a prohibited substance last spring. Fans would later learn that the four dogs finished in second place with four-time champion Dallas Seavey, and that the controlled substance was tramadol, an opioid pain medication.

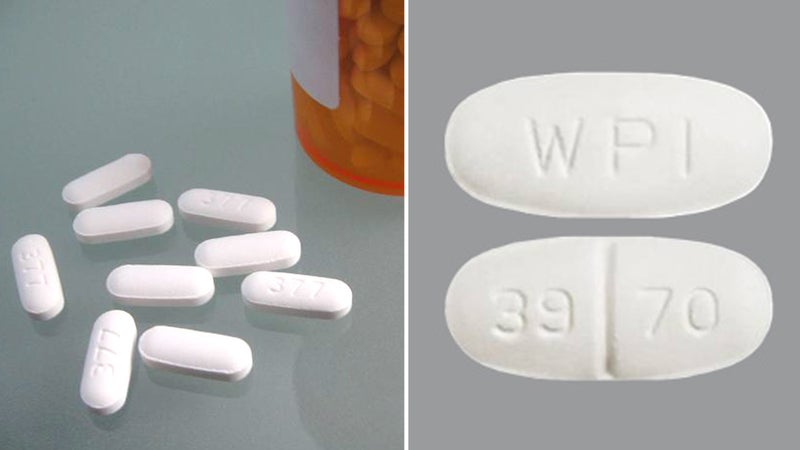

The world of dog sports exploded with speculation, in part because the details of the find were so unlikely: tramadol is a not a known performance-enhancing drug for dogs, and, based on its half-life, it appeared to have been administered at the very end of the race, possibly after the dogs had crossed the finish line and before they were tested six hours later.

The scandal also plays into the public’s fears about canine athletic feats that seem, from a distance, unbelievable. Headlines about an elite musher caught “doping” seemed to confirm doubts—at least among those who have never seen an actual sled dog team in action—that the dogs’ innate athleticism is a little too good to be true. The events have stirred up questions about the sport as a whole, as well as the role of the Iditarod Trail Committee (ITC) in representing an athletic community that’s anything but cohesive.

The 2017 Iditarod ended in March, and the ITC’s delay in announcing the news has fueled plenty of theories. Maybe Dallas administered the drug himself to access little-known benefits; maybe, since tramadol comes in white tablets that look similar to metronidazole, a common antibiotic prescribed for diarrhea, the dosing was a mixup on the part of a sleep-deprived vet tech or dog handler. In a series of recent videos, Dallas, swearing his innocence, suggests other possibilities: The dog food or urine samples may have been adulterated during their chain of custody. Most disturbingly, he suggests the drug may have been administered by a competitor or spectator grown frustrated with the Seavey family’s recent dominion over the sport. And although the vast majority of racers expect to lose money (the phrase “IditaDebt” should need no explanation), there is money, a Dodge Ram 4×4 truck, and sponsorship on the line for elite finishers, upping the stakes considerably.

I spoke to Jeff King, four-time Iditarod champion, who was adamant that even top finishers don’t compete for fame or money—and that Dallas, an articulate and handsome former world-class wrestler and reality TV star, had plenty of other routes to glory. “I saw [Dallas’ father, three-time champion] Mitch Seavey three days ago, training out in a remote part of Alaska, hundreds of miles from civilization,” King says. “Mountains are snow-covered, caribou running up and down the road.” Spectators see adoring crowds at the race’s famous burled-arch finish line in Nome, but they rarely conceive of the thousands of hours of running and training and cuddling and camping that saturate a dogsledder’s life year-round. “You don’t do this sport if you don’t love dogs first and foremost.”

As for the ITC’s delayed response, King is sympathetic. “I’ve been a board member,” he says. “You do the best with what you’ve got. We are continually tasked with being a local event that gets global exposure.”

It’s not just exposure: The Iditarod—the “Last Great Race”—is a full-on global symbol, at once proud and reluctant, tasked with organizing a statewide sporting event on a shoestring budget while also defending itself against attacks on the sport itself. (PETA major sponsor Wells Fargo to withdraw from the race.) The ITC has responded to conflicts in recent years by becoming more conservative and controlling, but this fearful attitude does little to promote an event that, ultimately, is designed to celebrate the Final Frontier and the bond between dog and musher.

Danny Seavey, Dallas’ older brother, is blunt about this. “The Iditarod board has shown an almost uncanny ability to make a big problem out of little problems,” he said, citing an incident in 2015 where front-runner Brent Sass was disqualified from competition for carrying an iPod Touch. (Racers were not allowed to carry two-way communication devices until this past year, when race directors voted to .)

But as the current predicament shows, the Iditarod’s tight grasp on participating mushers is fraught. A sport like dogsledding—which plays out in the middle of wilderness, far from fans or most sane human beings, with animal welfare on the line—is suspect to all kinds of misinformation. It needs to embrace transparency in order to grow.

One of the Iditarod’s more controversial decisions was the implementation of Rule 53 in 2016. Nicknamed the “gag rule,” it orders mushers not to speak about anything that might reflect badly on the race or its corporate sponsors, starting from the day they sign up until 45 days after the last team crosses the finish line. Since signups begin in June, the rule basically silences mushers in every month but May. Several racers I spoke to (not quoted here) wanted to know when this article would be posted to see whether its publication date allowed them to speak freely. Dallas Seavey, in his first video about the tramadol incident, said he expected he would be banned from the race due to the gag rule. He has since withdrawn from next year’s race in protest.

On a practical level, the gag rule protects the Iditarod’s own media relationships and lucrative contracts, but it also stifles that doesn’t align with the agendas of corporate sponsors, and prevents racers from speaking up about dangerous conditions for themselves or their dogs. Dogsledding, like most adventures, lives through its stories, and censoring those stories chips away at a core tradition in the sport.

“Iditarod has spent years building up an event that is heavily romanticized, rooted in heritage and history, these basic stories of man and dog, man versus nature, etcetera,” Lisbet Norris, a three-time Iditarod finisher, told me. “But the image isn’t bulletproof, and lack of information leaves a vacuum that is filled with speculation and hearsay.”

But change may be coming. On October 23, 86 members of the Iditarod Official Finishers Club (IOFC), a self-proclaimed “players union” for Iditarod mushers, signed a press release urging the ITC to repeal Rule 53 and to implement a stricter drug policy, including a full and transparent investigation and clear penalties. The IOFC will meet again next month to make further recommendations.

And, most likely, the ITC will listen. There’s charm and power in a world-class competition that’s never outgrown its provincial roots, and—though it occasionally leads to inexpert PR moves—the hometown vibes that make the Iditarod vulnerable will also be what saves it, both from this scandal and others. It’s a global symbol staffed almost entirely by volunteers, a bipartisan celebration of Alaska, and a place to see some really great huskies in action. Rather than cultivate a fearful, defensive attitude, the race should focus its limited resources on promoting its deep traditions of storytelling, bonds between mushers and dogs, quirky traditions, and connections to village Alaska.

“If you took the entire top ten out of the race, and took everyone in a leadership position and fired them, there would still be an Iditarod next year,” Danny Seavey told me. “It has nothing to do with media contracts or who’s getting paid big bucks. It’s a social event. Everyone comes together, and Bob out of his cabin puts the trail in for the next 20 miles, and there’s the guy that always gets up and makes the parking setup. You can’t take that away.”

Or as one elite musher puts it: “I would run the Iditarod if the prize was a bag of dog food.”