IT'S TIME TO SWIM, and so I kick my legs over the side of the tandem surf ski—a sit-on-top fiberglass racing kayak—and drop into the 55-degree currents and rolling breakers off South Africa's Cape of Good Hope. Salt stings my eyes, and the water snaps from black to blue, with blurry ropes of kelp dissolving into the shadows and the skis' rudders hanging above. Then I resurface.

“You must not dither,” shouts Lewis Gordon Pugh, the world's greatest cold-water distance swimmer, as he treads water near his ski. “Swim like you're running through a minefield.”

Right, the sharks. We're bobbing off Cape Point, with False Bay stretching eastward. The exercise is the second of three frigid dips I've joined Pugh for—a kind of initiation into his training regimen before a big swim. The first was a lap across chilly Silvermine reservoir, atop Cape Town's Table Mountain; this one is largely ceremonial, just 20 ocean yards, but it happens to take place at one of the most famous gathering spots for great whites. If you've seen a photo of an airborne Jaws tearing through a seal, it was likely taken in False Bay.

��

��

��

Dawid Mocke, the better half of my tandem, mans the craft while Pugh coaches. If you're going to swim off the stormy Cape, there's no better team to watch your back. Mocke is the current world champion of surf-ski racing, while Pugh, a Brit who's lived in South Africa on and off his whole life, is “the Ice Bear.”

��

��

��

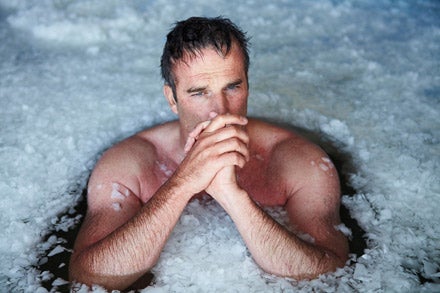

Over the past decade, Pugh—a six-foot-one 40-year-old with sandy-gray hair—has completed swims of a kilometer or more in the world's frostiest places, all in an effort to call attention to climate change: across Whaler's Bay, at Antarctica's Deception Island; down the 127-mile length of Norway's Sognefjord; around the northern tip of Norway's Arctic Spitsbergen island; and, in 2007, across a kilometer of open water at the geographic North Pole. That swim froze the tissue in his hands and left his fingers without feeling for four months. It also produced a previously unknown condition involving a urine icicle. “You don't know pain until you've had a stalactite in your cock,” Pugh told me, wincing.

��

��

��

In April, when I visit, he is in the final stages of training for a May swim across one of several mile-long lakes at the foot of Everest's Khumbu Glacier. Though the water won't be as cold as at the polar oceans, it won't be as buoyant, either. The altitude, more than 16,000 feet above sea level, could force him to use the slower breaststroke, not his usual crawl, in order to breathe. Minimizing time in the water is critical for Pugh, since his feats always adhere to the rules of the English Channel Swimming Association: a Speedo, cap, goggles, and nothing else.

��

��

��

I follow his rules, too, but my strokes evoke a crippled seal rather than a trained swimmer, which may be the reason Pugh's voice has a hint of real concern as we stroke back to the skis. In Pugh's and Mocke's circles, everyone knows someone who's been attacked. There's Shark Boy, the distance swimmer who's missing a leg, and Mocke's friend Lyla Maasdorp, who borrowed his ski and had the back half of it bitten off. To add to my anxiety, 20 minutes ago Mocke and I felt a firm thump against the hull that might have been imaginary—until a second jolt came just as we were exchanging was-that-you's. But today the sharks are picky. We make the skis and finish our four-mile tour of the Cape.

��

��

��

PUGH LIVES WITH HIS WIFE, Antoinette, her son, Finn, and their two small dogs, Kanga and Nanu, in the bucolic Cape Town suburb of Noordhoek. He begins his days boxing, lifting weights, and running sand dunes with his fitness trainer, Craig Scarpa, 35, around the mountain in Hout Bay. Some mornings he swims laps in Silvermine reservoir, above the waters where he got his start in 1987.

��

��

��

At 17, Pugh, who was a lifeguard at Cape Town's Clifton Beach, began taking lap-swimming lessons with his high school team. A month later, he made the difficult four-mile crossing from Robben Island—the notorious prison where Nelson Mandela was held during the apartheid era—back to Cape Town. Six years later, Pugh swam the 21-mile English Channel. “As a swimmer, I'm just above average,” he told me, “but I have a great deal of desire.”

��

��

That desire and Pugh's determination to conserve the places he loves come from his late father, Patterson Pugh, a former admiral in the Royal Navy and the Queen's personal orthopedic surgeon. The elder Pugh was present at the first British atomic-bomb test, in 1952 off western Australia, where he was responsible for determining the causes of death and levels of radiation in the marine life that washed up after the blast. This had a profound effect on him; he later told his children that he saw an X-ray view of his hands through his closed eyelids. In 1980, Patterson retired from the navy and moved to South Africa, for its temperate climate. He used school holidays to bring Lewis and his older sister, Caroline, to many of the country's famous national parks.

��

��

��

After earning law degrees at the University of Cape Town and then at Cambridge, Pugh worked as a maritime lawyer in London. In 1998, he joined the British Army's elite Special Air Service regiment as a reservist. He wasn't able to swim much with his weekends occupied by paratrooping, but he did learn a soldier's toughness. It was after his discharge, in 2003—the same year the SAS was deployed to Iraq—that he decided on his mission: to claim swimming firsts and use the publicity generated to highlight the damage caused by climate change.

��

��

��

“When I came to it, the only swims that were left were the really cold ones,” he admits. But, with many of those icy reaches melting at alarming rates, the niche fit well with Pugh's conservationist mission. His first break as an activist came in 2005, when he called then–prime minister Gordon Brown after his Spitsbergen swim to tell him that, yes, the glaciers really were melting. A short time later, Brown appointed Britain's first climate-change minister.

��

��

��

Now Pugh swims full-time. His record-breaking Norway swims, down Sognefjord in 2004 and then off Spitsbergen, helped him land sponsorships and corporate speaking gigs where he folds his environmental message into motivational business lectures. Speedo and South African retailer Pick n Pay fund his expeditions, while he supports his family by giving an ever-growing number of speeches—currently about 85 a year. After the Everest swim, he hopes to increase that total to more than a hundred.

��

��

��

��

��

��

��

��

��

��

��

At 17, Pugh, who was a lifeguard at Cape Town's Clifton Beach, began taking lap-swimming lessons with his high school team. A month later, he made the difficult four-mile crossing from Robben Island—the notorious prison where Nelson Mandela was held during the apartheid era—back to Cape Town. Six years later, Pugh swam the 21-mile English Channel. “As a swimmer, I'm just above average,” he told me, “but I have a great deal of desire.”

��

��

��

��

��

��

��

��

��

��

��

That desire and Pugh's determination to conserve the places he loves come from his late father, Patterson Pugh, a former admiral in the Royal Navy and the Queen's personal orthopedic surgeon. The elder Pugh was present at the first British atomic-bomb test, in 1952 off western Australia, where he was responsible for determining the causes of death and levels of radiation in the marine life that washed up after the blast. This had a profound effect on him; he later told his children that he saw an X-ray view of his hands through his closed eyelids. In 1980, Patterson retired from the navy and moved to South Africa, for its temperate climate. He used school holidays to bring Lewis and his older sister, Caroline, to many of the country's famous national parks.

��

��

��

After earning law degrees at the University of Cape Town and then at Cambridge, Pugh worked as a maritime lawyer in London. In 1998, he joined the British Army's elite Special Air Service regiment as a reservist. He wasn't able to swim much with his weekends occupied by paratrooping, but he did learn a soldier's toughness. It was after his discharge, in 2003—the same year the SAS was deployed to Iraq—that he decided on his mission: to claim swimming firsts and use the publicity generated to highlight the damage caused by climate change.

��

��

��

“When I came to it, the only swims that were left were the really cold ones,” he admits. But, with many of those icy reaches melting at alarming rates, the niche fit well with Pugh's conservationist mission. His first break as an activist came in 2005, when he called then–prime minister Gordon Brown after his Spitsbergen swim to tell him that, yes, the glaciers really were melting. A short time later, Brown appointed Britain's first climate-change minister.

��

��

��

Now Pugh swims full-time. His record-breaking Norway swims, down Sognefjord in 2004 and then off Spitsbergen, helped him land sponsorships and corporate speaking gigs where he folds his environmental message into motivational business lectures. Speedo and South African retailer Pick n Pay fund his expeditions, while he supports his family by giving an ever-growing number of speeches—currently about 85 a year. After the Everest swim, he hopes to increase that total to more than a hundred.

��

��

��

AT LEAST THERE are no sharks in the ice pool. Pugh's third test for me is his customary pre-expedition cold-water acclimatization, which he'll do once a day over the next week. The pool in question is of the circular, four-foot-deep, Walmart variety, and the only place in Cape Town that produces enough ice to adequately chill it is the I&J fishing wharf. The place is a long two-story warehouse where trawlers park to unload their catch and undergo repairs.

��

��

��

The gatehouse guard makes several incredulous phone calls about the two guys who claim they have permission to set up a pool on the dock. Then he raises the gate and we find our spot between stacks of bundled nets and pallets loaded with 55-gallon drums of motor oil. Several workers in diesel-stained coveralls immediately begin to help. The ice? Over there. One guy disappears and returns driving a forklift carrying a one-ton bin of chipped ice, and then a second. In they go. Another man appears with a fire hose, which spews some kind of black gook everywhere before water eventually flows out.

��

��

��

The pool fills. Never mind the ice; we're the two pale dandies in Speedos in the middle of an industrial park. Mine is too small, prompting Pugh to jab, “Borat wouldn't wear that.” There is a great deal of laughing around us, but Pugh turns serious. “Now listen to me,” he says. “You're committing 100 percent to ten minutes. You know you've got the strength inside to do it.”

��

��

��

It's at this moment that I understand the difference between a polar bear plunge and what Pugh's asking of me. We'd never discussed a specific goal, but ten minutes sounds long, and the bath looks cold—in the low forties, he estimates. “Take your mark, get set, go,” he suddenly barks. “Just walk in and sit down.”

��

��

��

I obey. The wind goes out of me, and I gasp as the pain of a full-body ice-cream headache hits me. The urge to stand up and leave is strong, but I'm focused on an imaginary stopwatch ticking down in my head. I've flown halfway around the world to sit in this ice pool and, damn it, I'm going to succeed. After a few seconds, the fire eases, though not in my feet, and I can feel my skin contract and stretch tight over my frame.

��

��

��

“I want you to say, 'I can do this,'” coaches Pugh. What comes out is mostly a series of primate noises. Pugh climbs in and sits against the side of the pool like it's a hot tub. He looks calm and peaceful, as if he's thinking about what beer to order the next time the waitress comes around. I try to copy him and last only a few seconds. Then Pugh decides the water could be colder. He gets up and begins breaking chunks off the floe circling the middle of the pool—and then drops them on top of me. “Break it up! Break it up!” he shouts. I try, but bolts of pain are shooting through my hands. After nine minutes, I can acutely feel the warmth of my core, but my palms and the soles of my feet ache worse. It's impossible to block them out.

��

��

��

Finally, Pugh shouts “Time!” and we climb out. The 60-degree air feels strangely warm, and I'm too cold to shiver or run for my parka. The shivering starts a few minutes later and is strong and uncontrollable. It's the sort of deep cold that isn't abated by blasting the car's heater.

��

��

��

That night at dinner, Pugh is subconsciously massaging his fingers—the same digits that were frostbit on his Arctic swim—as he talks. Eventually he turns to me.

��

��

��

“Do your fingers tingle?” he asks.

��

��

��

“That's weird. Mine don't hurt at all,” I say, ribbing him. “You know, once you have nerve damage, it's often recurring—”

��

��

��

But before I can finish, Pugh sticks his fingers in his ears, drowning me out—“Lalalalalala”—with another one of his mind-control techniques.

��

��

��

“No, seriously,” he asks again. “Yours don't tingle?”

��

��

��