After skate-and-surf auteur Stacy Peralta went from Sundance favorite to box-office millions with the films Dogtown and Z-Boys and Riding Giants, board sports get the documentary treatment once again with the December 2 national release of First Descent: The Story of the Snowboarding Revolution, from New York–based producer-directors Kemp Curley and Kevin Harrison. But the film is only half Dogtown-style history lesson. Woven throughout archival clips and interviews with industry founders like Jake Burton and Tom Sims is footage from a 2005 backcountry epic that may make First Descent the greatest snowboard porn ever. Backed by Universal Pictures and Mountain Dew—the latter making its first foray into film production—Curley, 36, and Harrison, 35, childhood friends from Fairfax, Virginia, assembled a five-rider dream team and 25-person crew for a multigenerational smackdown on the powder-covered steeps of Alaska’s Chugach Mountains. The athletes: snowboard pioneers Shawn Farmer, 40, and Nick Perata, 38; all-mountain legend Terje Haakonsen, 31, considered by many to be the world’s greatest rider; and freestyle wonder kids Shaun White, 19, and Hannah Teter, 18. JUSTIN NYBERG caught up with Curley and Harrison to find out about the making of the film—and why following Shaun White off anything is a bad idea.

first descents

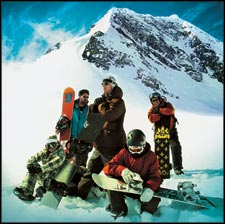

BOARD MEETING: From left, Hannah Teter, Shawn Farmer, Terje Haakonsen, Shaun White, and Nick Perata

BOARD MEETING: From left, Hannah Teter, Shawn Farmer, Terje Haakonsen, Shaun White, and Nick Perata

OUTSIDE: What prompted you guys to make this film?

HARRISON: We started snowboarding 20-plus years ago; we used to make our own boards. It’s always been a bit of a passion for us. And it went from being this outcast hobby all the way to where it is today—a billion-dollar industry and Olympic sport.

CURLEY: You have this chaotic rise of the sport in such a short time. It’s a fun story to tell.

Any surprises as you went through the history?

H: Most people assume snowboarding started in the late sixties and seventies, but we saw this footage of people snowboarding in Chicago in the 1930s. The boards are made of whiskey barrels, with these two little places to put your feet. There’s a whole family doing their thing in brimmed hats and overcoats going down a hill. It’s classic.

Why throw in the backcountry trip?

C: We’re using the term “fusion documentary.” Alaska is the pinnacle of snowboarding, and we wanted to get the most progressive representation of the action.

H: The history-lesson thing is great, but it definitely appeals to an older crowd. The young kids want to see the latest tricks. About 30 percent is history, and the rest is modern-day. We thought it would be a cool way to keep it entertaining for everybody.

Any scary moments up there?

H: We have a cameo by Travis Rice, one of the best all-around snowboarders in the world, where he triggers a giant avalanche while he’s coming down a run. He gets completely covered up. I thought we were going to have to charge over there and do a search and rescue, but he eventually rode out of it. He’s no stranger to the backcountry. He was ready to go back up and do another run.

Snowboarding isn’t short on personalities. How did you settle on these five?

H: They’re the perfect group. They span the generations of the sport. Shawn Farmer was the original wild man of snowboarding. He would jump off giant cliffs, go down big mountains, and party just as hard. Nick pioneered the heli-boarding scene in Alaska. Then you get Terje Haakonsen, maybe the best ever. He dominated the sport in the nineties but has always been kind of a mystery, someone who let his actions speak for him.

C: And then Shaun White and Hannah Teter, who are the mainstream now. They’ll probably go to the Olympics.

That’s a lot of ego to fit into one helicopter. How did everyone get along?

C: Nick migrated right into mentoring the rookies, White and Teter, which is what we were hoping for. But we were surprised to see Farmer doing it, too, making sure they were safe. He wasn’t going to tell them, “Don’t jump that cliff,” but he would help explain the best way to get through it.

H: But the new guys taught the old guys stuff, too, you know, because they took freestyle riding up to the old guys’ world.

Forty-year-olds trying to keep up with Shaun White? Sounds like a recipe for disaster.

H: We have this one kicker session on a jump we built. The guys were bombing in at 50 miles per hour and launching. Shaun did a 720 that he claims was the biggest he’s ever done—probably a 120-foot gap. Farmer was last, and he had to build up his courage to go for it. He went down really hard, had kind of a reality check—bruised ribs and a big hematoma on his elbow. But he still charged some good runs after that.

After all this, any ideas where the sport is headed?

C: With the mainstream money that’s involved now, it can go anywhere.

H: It’s always been dictated by the riders—where they want to take it. As Jake Burton says, “If you can tell me where snowboarding is going, you’ve got a job.”