THE COLLECTIVO SPED down the valley, flicking past cornfields and eucalyptus groves and little adobe villages where tomato-cheeked women in bowler hats and Day-Glo skirts squatted in the dust, waiting for a ride to the market in Huaraz. It was early June. The hillsides were aflame with yellow broom, and the tributaries rushing down the quebradas from the high glaciers of the Cordillera Blanca were running clear and full. Every few miles another giant, fantastically fluted peak would swing into view and someone in the van would call out for a photo stop, but by the time the driver got the message and took his foot off the gas, the moment was gone and we’d wave him on. Then, just outside the grimy hamlet of Mancos, we came around a corner and it was right there, filling the windshield, too big to believe. Everyone yelled at once, the driver laughed and pulled over, and the five of us tumbled out onto the side of the road.

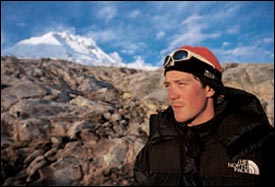

Chris Trimble scales Huandoy

Chris Trimble scales Huandoy Hans Saari climbs Huandoy

Hans Saari climbs Huandoy Cutting edge: Saari side-slipping down the Shield, 21,000 feet and dropping

Cutting edge: Saari side-slipping down the Shield, 21,000 feet and dropping Saari and Nat Patridge’s trial run on Huandoy

Saari and Nat Patridge’s trial run on Huandoy Supper by headlamp

Supper by headlamp

Nevado Huascarán. At 6,768 meters (22,205 feet), it’s the highest mountain in Peru, and the loftiest peak in the tropics. (Argentina’s Aconcagua, at 22,834 feet, is the highest in South America.) Huascarán is two peaks, actually: Huascarán Norte and the slightly taller Huascarán Sur, both massive snow domes connected by a vast snow field called the Garganta; you could land a space shuttle up there.

Squinting into the morning sun, Kristoffer Erickson, our de facto expedition leader, pointed out the ruta normale, the standard climbing route to the summit of Huascarán Sur. Established by a German-Austrian expedition in 1932, it goes up the south side of the lower glacier, angles through a serac-studded icefall to the Garganta, then straight up the north shoulder of Huascarán Sur to the broad summit plateau. In 1978, French extremiste Patrick Vallençant made the first ski descent via the ruta normale. Since then it’s been skied and snowboarded many, many times.

Now Erickson traced another line. It was breathtakingly direct, cutting from the icefall onto a great chevron-shaped snow face and then back along a sharp ridge—the West Rib—to the summit of Huascarán Sur. The face was the crux. Erickson estimated it at about 1,500 vertical feet and 55 to 60 degrees. It was oddly smooth and unbroken, as if it had been hacked out of the mountainside by a giant cleaver. El Escudo, the Peruvians call it. The Shield. As far as anyone knew, it had never been skied.

Erickson, 27, is an affable and self-assured former high-school swimmer who was born and raised on the plains of north-central Montana. In 1993 he enrolled at Montana State University, in Bozeman, where he planned to major in landscape architecture. He took up photography instead, and he soon fell in with the boisterous local climbing crowd. Along with an ice-climbing buddy named Hans Saari, a sober, quietly competitive housepainter with a humanities degree from Yale, Erickson developed a passion for ski mountaineering, the once-obscure sport that involves carving turns down “slopes” previously considered to be climbing routes.

In 1998, after a series of noteworthy first descents in Montana’s Beartooths and Wyoming’s Tetons, the duo talked The North Face into sending them and four friends to Peru to shoot a ski flick on an absurdly steep, Matterhorn-like peak called Artesonraju, a few quebradas, or deep valleys, north of Huascarán. (Their footage became the lead segment of the DesLauriers brothers’ 1999 film Altitude.) Now Erickson and Saari, who is 30, were back, with a new crew of Peru first-timers: Chris Trimble, 32, a voluble, redheaded snowboarder from Basalt, Colorado; Nat Patridge, a laconic, 30-year-old ski guide from Jackson Hole, Wyoming; and me. A sixth member of the expedition, 32-year-old Stephen Koch, a Jackson-based snowboarder, would join us a few days later.

On their way to Artesonraju two years earlier, Erickson and Saari had scoped the Shield, and found it blue and sheeny—far too icy to hold a ski’s edge. But because the past winter had been more severe than usual, it now looked as if the left side of the Shield might be covered in snow. Skiable snow.

IF YOU’RE LYING in bed in Huaraz on a June morning, acclimatizing (the city sits a heady 10,200 feet above sea level) or just recovering from a night at the Tambo, the nightclub where climbers, tourists, and locals mix, here are some of the sounds you might hear:

A rooster with a throat infection.

Distant tuba bands playing dirges.

Pickup-truck-mounted megaphones blaring political slogans.

And, without fail, the metallic jouncing of rebar being carted to construction sites.

In Huaraz, rebar is serious business, a legacy of the terrible earthquake of May 31, 1970, which leveled the city’s unreinforced adobe buildings and killed 20,000 people, half the population. (All told, the death toll in northwestern Peru came to 70,000, making the quake the worst natural disaster in the recorded history of the western hemisphere.) A tragedy like that could haunt a place for generations, but Huaraz today is a vibrant boomtown of 100,000-plus whose prosperity is due to two new nearby Canadian-owned copper and precious-metal mines—and to adventure tourism. With easy access to climbing and trekking in both the Cordillera Blanca and the Cordillera Huayhuash, the city has become a mandatory stop on the Gringo Trail, a sort of Andean Chamonix.

In the two years since Erickson and Saari last visited, the place had changed dramatically. Internet cabinas had sprung up everywhere, a half-dozen new cash machines had gone in around the Plaza de Armas, and there were even seafood restaurants. Yet the two had gotten their biggest shock when we checked in at La Casa de Zarela, the little hillside hostel run by Erickson’s friend Zarela Zamora Lopez. Erickson and Saari expected to find the usual crowd of penny-wise climbers on the back terrace, one of the pension’s prime attractions. What they weren’t prepared for was the half-dozen skiers and snowboarders hanging there, too. One of them, a rawboned Scotsman, had just reprised Vallençant’s classic descent of the west face of Yerupajá, in the Huayhuash. Next to him, two longhaired French snowboarders lounged in the sun, rolling joints and waiting for their photographer to recover from a bout of “gastro.” As soon as he did, they were going to ride Huascarán Norte.

Saari shook his head in disbelief. “Two years ago people would see our skis and just say, ‘What are you doing?'” he muttered. “Now it seems like everybody’s down here.”

“Maybe it’s time to stop making movies,” Trimble said.

He had a point. Even as Saari lamented the ski bum’s rush on Huaraz, he knew that he and Erickson had had a hand in kicking it off. Make an over-the-top video like the one they filmed on Artesonraju, and you’re going to draw a host of imitators. On the other hand, what choice did aspiring backcountry careerists have? Ski mountaineering isn’t pro golf, and the only way to make it pay is to go bigger, get higher, publish more articles, and make more movies.

Even so, Erickson and Saari insisted that this trip was to be casual and relaxing—a vacation. The previous fall the two had been witnesses to the avalanche on Tibet’s Shishapangma that killed alpinist Alex Lowe, 40, and cameraman Dave Bridges, 29, and neither felt ready to attempt something of that magnitude again, much less return to the Himalayas. All he and Saari wanted, Erickson said, was to kick back and show their friends Peru.

But was it really possible for these guys to chill? In a month, Erickson, Saari, Patridge, and Koch—all of whom worked for Exum Mountain Guides—were due in Jackson Hole for the summer climbing season, a two-month slogfest in which they might clear $12,000 each. The stake would carry them through the rest of the year, but during the season they’d have next to no free time. As such, this “vacation” represented their best chance to stay on the radar of potential sponsors. What’s more, this was their last opportunity to secure summerlong bragging rights within their fraternity of climbers and guides. As they all well knew, reputations are made in the off-season. If they didn’t come back from Peru with some spectacular first descent, someone else would.

Beyond all that, I suspected, there was something else—a simple, burning need to take things one step further. Sitting there on Zarela’s terrace, I suggested as much to Erickson.

He shook his head. “We don’t go out there to up the ante every single time,” he said. “We’re out there because it’s what really fuels us, gives us the drive to do everything else we do. It’s not to outdo anybody. It’s the camaraderie, the bond between us, the excitement.”

Whatever the motive, I replied, the effect is the same: Your next expedition winds up being heavier than the thing you did before. Erickson laughed.

“That is true,” he said.

STEPHEN KOCH KNOWS how to make an entrance. Blond, muscle-bound, and rakishly dressed in crisp khakis, a porkpie hat, and a pink aloha shirt, he strode into Zarela’s, set down two giant duffels, and cheerfully crushed all our hands in turn. Then he hoisted himself up onto the stuccoed eaves of the roof and made his way around the courtyard, hand over hand. “Need a little workout after that bus ride,” he explained, panting a little.

Erickson might have been our leader, but Koch was our rock star. Born in San Diego, he skipped college, moved to Wyoming, and taught himself to board, startling the locals with his out-of-the-blue first snowboard descent of the Grand Teton, in 1989. Though he spends his summers guiding, like everyone else, he also has a mediagenic multiyear quest: to become the first snowboarder to ride the Seven Summits, the highest peak on each continent and Oceania. So far he’s knocked off five and is seeking more sponsorships (Burton Snowboard Company is already backing him) for an attempt on the last two—New Guinea’s Carstensz Pyramid this year, and the formidable north face of Everest in 2002.

Despite all he’s done, Koch was new to Peru. He’d meant to come down on the Artesonraju trip in 1998, but an avalanche that spring on Mount Owen, in the Tetons, got in the way. The slide carried Koch 2,200 feet, broke his back, and blew out both of his knees. Now, after a full year of therapy, he was again ready to charge—and charge he did. That night at Tambo, Koch delighted the mostly female crowd by ripping off his shirt and clearing a swath on the dance floor with his gyrations.

“Did you know Hasbro and The North Face are coming out with a new Stephen Koch action figure this Christmas?” Trimble said one morning over breakfast. “It’s gonna have a little snowboard and two little ice axes for accessories.” He mimed the toy, making hand-over-hand ice-climbing motions. Everybody laughed, but the truth is we were grateful for Koch’s infusion of energy. It was good to have someone impulsive and headstrong in our midst. Until his arrival, the rest of us had been bumping along in professional nice-guy mode, carefully deferring to one another with the jokey bonhomie of package tourists.

The next morning we huddled with Koky Casteneda, a local guide and an old friend of Erickson’s who knows all the climbing news. Saari outlined two possibilities for our first project: the Ferrari couloir on Alpamayo and the north face of Huandoy. (The Shield isn’t the sort of run one warms up on.) Both options were audacious. Huandoy is a 55-degree slab bordered by a sickening 1,200-foot overhang, while the Ferrari is a 60-degree ice runnel ten or 12 feet wide.

Everyone knew that to ski the Ferrari would blow the collective mind of the climbing world. But Casteneda, who had just returned from Alpamayo, had discouraging news. “There were 40 people in base camp,” he reported. “It’s like ants. Every morning there’s a race to get out of camp and be first on the face.” Even if we won that race, then what? Would we ski it with everyone else coming up the same line?

That night another Bozeman climber dropped by Zarela’s. “That’s funny,” he said after hearing our plans. “There’s this other guy from Jackson who’s trying to do the same routes.”

“He’s on skis?” Saari asked.

“I think so,” the Bozemanite replied. “His partner got sick on Alpamayo, but after that I know they went to Huandoy. Now they’re on Huascarán.”

An almost palpable shiver ran through the group. Before leaving the States, Saari had posted a brief write-up of the trip on the Exum Web site. Koch, it turned out, knew the other skier. His name was Brendan O’Neill; he worked at Jackson’s Mountain High Pizza Pie. Could a guy from home be doing a little poaching?

THE TRAIL TO HUANDOY zigzagged up through chest-high thickets of lupine in riotous purple bloom. Paintbrush and miniature organ-pipe cacti brushed our boots, and we passed through a last, gnarled grove of papery-barked quinual, one of the world’s highest-dwelling trees. Then, at 15,400 feet, we crossed over a little ridge in the moraine and dropped down to a turquoise glacial tarn: base camp.

After hearing about O’Neill, Saari had checked the logbook at the local guides’ office in Huaraz and discovered that O’Neill and a partner had indeed climbed Huandoy Norte but had left their skis at base camp. Good news. The peak was still a potential first descent, and we’d quickly decided on it.

Above base camp we could see a series of smooth granite slabs, then the toe of a massive glacier leading back into the giant bowl formed by Huandoy and its sister peak, Huandoy Oeste. The first afternoon we made out a faint trail leading up the glacier—O’Neill’s bootpack—but above that, nothing.

“It’s going to be burly, really burly,” said Saari. “It needs lots of traverses and rappels.” He looked around, smiling. “I’m psyched.”

After three days of acclimatizing, we decided to take a warm-up run on a ramp dropping down from the flanks of Huandoy Oeste. To me it was the only line on the whole mountain that looked remotely skiable. But when I got to the crux, a funneling, 53-degree couloir that connected the upper part of the ramp to the slightly mellower lower slopes, I changed my mind. Ditching my skis and poles, I climbed the rest of the way up with an ice ax in each hand.

A strange sight greeted me up on top: thousands of foot-high ice towers, apparently created by fierce sun and a lack of wind. They’re known as penitentes, and the name is apt: They looked like cloaked pilgrims plodding mindlessly toward some holy summit where they might or might not be redeemed. Luckily, the towers turned slushy with the heat of the day and gave way easily beneath the pressure of turning skis and boards.

The slope, which we later dubbed Los Bonitos Penitentes, topped out at about 18,500 feet and offered 50-degree turns over a terrifying precipice. Everyone gritted their teeth as Casteneda threw his first few turns. He’d been on skis for only a couple of seasons, and his self-taught technique was ragged. But he kept his stance low and wide and calmly shoulder-steered clear of trouble.

Trimble went next. I watched him, impressed by how casually he shifted his weight when turning from toeside to backside. Too casually, perhaps; an instant later his board shot out from under him and he went down hard on his butt. At first it was almost funny. He wasn’t sliding fast, and the expression on his face was more of annoyance than fear. Then he began to accelerate.

“Get a tool in!” Erickson yelled.

Not a chance. Trimble was on his back, enveloped in a cloud of flying ice chips, straining hard to keep the bounces from becoming cartwheels. Though the pitch gradually flattened below, it wasn’t at all clear that he would be able to avoid being swept over the cliff at the very bottom. And then, suddenly, he got his edge in and stopped. Shaken but unhurt, he sat up, swallowed hard a few times, and waved weakly toward us. By the time we caught up to him, the Chattering Skull—one of Trimble’s many nicknames for himself—was back to his customary self-mockery.

“How’d you like that one?” he said. “Bucky’s Wild Ride.”

THE NEXT DAY BROUGHT the first of the debates that would rattle and eventually fracture our team. Castaneda left for a guiding job in Huaraz, and everyone except me wanted to ski Huandoy. (After the warm-up run, I quickly decided to stay in base camp and monitor the group’s progress via walkie-talkie.) Koch and Patridge lobbied for the north face proper, a route that would take the group left, or east, of a giant rock spur that runs down from the summit. Erickson argued forcefully for going right on the marginally gentler northwest slopes. The face proper was the most direct and “elegant” line, but there was a problem: a vertical rock band right at the top, a spot where the four Americans who first climbed the face, back in 1971, had been forced to bivouac.

“We could climb it and then rappel back over it on the way down, but are we gonna have the time to do all that in one push?” Saari wondered. On the other hand, he pointed out, going via the northwest slopes would mean an easier, rock-free approach and an uninterrupted ski descent. “In which case you’ve skied from the summit,” Trimble said, “but maybe not in the ultimate style.”

For two days we talked it over, sitting elbow-to-elbow in the shade of a large, leaning rock and staring up at the face in the afternoons, then tossing it over some more at night in the “conversation pit,” a circle of stones stacked between the tents. For a while the argument was a great, all-absorbing game—not unlike the fierce chess matches that Saari and Trimble engaged in every evening.

Finally it was time to vote. Northwest slopes prevailed, three to two. Relieved to have a decision, Erickson went to nap in his tent. By the time he woke up and returned to the pit, Koch had made a fiery speech and rallied everyone back to the face proper. Better to knock off the toughest line on the mountain, he argued, than leave some plum for a future O’Neill to pluck.

“That’s fine,” Erickson said. “You all go ahead. I’ll stay here.”

In some ways, he was acting the petulant schoolboy. Yet Erickson knew firsthand the consequences of overreaching in these mountains. In June 1997, having just graduated from Montana State, he had arrived here with his best friend, Rob Williams. When Erickson was sidelined with dysentery, Williams, 23, decided to attempt a hard route on Chopicolqui, immediately east of Huascarán, with Koky Casteneda, then an apprentice guide. Just below the summit of Chopicolqui, Williams succumbed to pulmonary edema. Over the next week, Erickson, Casteneda, and two others grimly fixed ropes to the summit so that Williams’s body could be lowered off the mountain.

Now, as Erickson restated his argument—the northwestern slopes provided more bailout options if something went wrong—everybody but Koch began to waver. In the end it was Nat Patridge who led the troops back across the divide between Koch and Erickson. “We’re much stronger and safer if we stay together as a team,” Patridge said. “I don’t care if the left is more aesthetic. I’m going right.” Koch walked away in disgust.

At midnight I watched the five of them leave camp and disappear over the toe of the glacier, penitentes marching to oblivion. Later, after daybreak, they were five specks on the open face, frying under the Andean sun. By noon, three of them had reached the ridge, and a fourth, Koch, was clawing his way up to join them. Patridge had turned back, stopping to rest—or so it appeared—at a rocky alcove halfway down the face.

Up on Huandoy, the clouds don’t roll in, they coalesce out of blue air, and a few minutes later I couldn’t see the peak at all. Erickson got on the radio. The four on the ridge wanted to go on and tag the summit, he said, but how was Nat doing?

“I don’t know,” I said. “I can’t see him anymore.”

The next three hours were tense. The four abandoned their summit bid to make sure Patridge was OK, but how best to reach him? A ski descent was out of the question—baked by the sun, the snow was unskiable. The four tried to skirt right and rappel down to the glacier by another route, but eventually they had to tiptoe all the way back across the bottom of the slide-prone slope they’d just climbed. At dusk they got to the alcove where I’d last seen Patridge, but he wasn’t there. Then, just before dark, the clouds lifted and I spotted him a thousand feet below the rest of the group. He was skiing.

BACK IN HUARAZ, we again contemplated the Shield. Only, after the failed summit bid on Huandoy and the scare with Patridge, it now seemed more daunting, not less so. Nor were the reports from people who’d been up on the mountain very encouraging. Saari suggested another option: Ranrapalca, the chiseled peak that looms directly over Huaraz.

It’s the south face of Ranrapalca that you can see from town, an incredible 60-degree slab overhung with seracs. It was, most everyone agreed, unskiable. Back in 1979, a 22-year-old Canadian named Peter Chrzanowski had attempted it only to take the most spectacular fall in the history of Peruvian skiing.

“After making only a couple of turns, I cartwheeled 2,000 feet down the entire face and somehow survived,” Chrzanowski recalled for me in an e-mail. “I was barefoot when I came to, and in a crevasse. I ate three days’ worth of sleeping pills while my climbing partner ran for help to the nearest village. This probably saved me from stress. I slept instead.” Chrzanowski, now 43, is a filmmaker and a gregarious oddball whom the ski world has never quite taken seriously—”Chernobyl,” some call him, or “Peter Should-NOT-Ski.” Still, he’s one of the sport’s original soul surfers, and the guys liked the idea of trying a descent of the northeast face of the mountain he’d made famous.

Huascarán or Ranrapalca? While this latest debate wore on, Koch e-mailed the suspected poacher, Brendan O’Neill, who’d returned to Jackson, asking if he’d skied or climbed the Shield.

“Climbed and skied ruta normale on Huascarán,” O’Neill replied. “The Shield looks fantastic, I want it. Black ice on the flanks, snow down the gut, but who knows how deep. I say check it out.”

Then, a day later, we heard that some new gunslingers—two skiers, a photographer, and a writer sponsored by an adventure Web site—had hit town. Saari and Patridge went off to do a little espionage under the guise of a welcome-wagon visit. The cyber-jocks were there to generate a daily online journal of their exploits and had two peaks on their list: Tocllaraju, which Erickson and Saari had skied in ’98, and Ranrapalca.

No time to lose. Erickson called a vote: Three to two for Ranrapalca, with Saari and Patridge dissenting. Then Erickson and Trimble began to have second thoughts. “There’s a better consolation prize on Huascarán,” Trimble noted. “Even if you don’t ski it, you still get to climb the biggest mountain in the range.”

As the discussion intensified, Koch seemed less and less interested. The next morning, just before heading down to the market to provision, we assembled for our “final” vote. Koch wore an aggrieved expression, as if it was all too tedious. “Whatever you guys want is fine with me,” he said. But that same night, he dropped out altogether. “I just want to swing ’em,” he said, miming an ice ax in each hand, “and not carry the board all over the place.” Koch searched out everyone’s eyes. “I’m just not psyched on the route.”

Saari stood up and, without a word, left the room. Erickson tried to remain diplomatic. “What are you going to do?” he asked Koch, with exaggerated politesse. Koch said he and Jim Earl, a friend from Bozeman who’d turned up in Huaraz, planned to try a new route on Caraz, across the valley from Huandoy. Later, Erickson was sharply critical. “You just don’t drop out of the expedition, and weaken the team, without warning,” he said. “I admire Stephen for speaking up, but to me it’s like he used the trip to get what he wanted from it, which was to figure out the scene in Huaraz. I could have asked numerous other people who would have been a much better asset to the team.”

It was hard not to see Koch’s decision as payback for Erickson’s stand on Huandoy, but Koch took pains to explain otherwise. He was “burned out on group decision making,” he said, and, certain that Huascarán would be all ice, worried that he might return from a month in Peru with nothing to show for it. On Huandoy he’d battled a bronchial infection and then fought his way up to the top, only to find the snow completely unrideable. There was no way, he said, he was going to haul his board up to 22,000 feet for another “nonstarter.”

AFTER THE QUIET of Huandoy, base camp on Huascarán was the definition of culture shock. Some 40 people were there, most of them on commercially guided climbs headed up the ruta normale. Long into the night, peals of laughter spilled from the big canvas tent where guides and porters gathered. Huascarán, it appears, has gotten a reputation as a big but not-too-difficult peak, a good place to burnish the résumé.

For three days, we moved up the mountain in 1,500- to 2,000-foot “baby steps,” which brought us to the foot of the icefall. From there, I planned to climb via the ruta normale and meet the others on the summit. On the fourth night, Erickson, Saari, Trimble, and Patridge puppy-piled into a tent in a crevasse just beneath the Shield, intending to make for the summit later that same evening.

Their alarm went off at 11, but it took three hours of high-altitude Twister to brew up, suit up, and get on their way. Fifteen minutes after leaving camp, Patridge ate a candy bar and immediately puked it back up. “But after that I felt great,” he said.

The first few hundred feet of climbing were nasty, but then the slope eased. Sure enough, there was snow on the left-hand edge of the Shield—some of it good, some of it death crust. Continuing up the West Rib, they climbed by headlamp until the moon came up. At dawn I looked south and saw two figures with skis on their backs heading up the summit plateau.

Saari and Trimble arrived at the summit at 9:15 A. M., with Erickson close behind. About the same time, some 500 feet below, on the ruta normale, I turned around, too exhausted to continue.

Above me, the final, crucial call of the expedition was at hand: descend by the Shield, or retreat by the ruta normale? “In a strangely lucid, intense discussion at 22,000 feet,” Trimble would e-mail later, “Erickson convinced me that I was going to accompany them down the Shield for the turns of a lifetime, and that the snowpack, which seemed sketchy on the way up—while breaking trail I triggered a terrifying ‘settling’ incident at around 3 A. M.—was actually ‘bomber’ and beautiful. He was utterly correct, and I slithered along into the abyss.”

After a beautiful ski down the West Rib, the foursome arrived at the top of the Shield about ten o’clock. Behind them, the sun was just coming up over the mountaintop. Edging right, they skirted the near-vertical peak of the Shield’s chevron. Then Patridge cut out onto the face, probing delicately with his pole and hopping an exploratory first turn. He nodded back to the group—and off they went.

“I’ve skied steeper slopes,” Saari said. “But the pitch was so consistent that there was a distinct feeling of, I don’t know, just being out there on a separate plane.”

Switching the lead every few turns, they descended partway and stopped to reassess. “The snow was firm, but it had a biteability to it, like chalk,” Erickson said. “Up high, you left hardly any tracks, just these little creases in the snow.” Lower down the snow softened, however, and they began, if not to relax, at least to open up, linking turns and reveling in, as Trimble put it, “the whole you-fall-you-die thing, the altitude, and the exposure, and the incredibly sustained pitch.”

They’d achieved what they came for, but it was all over in an hour. Trimble coasted to a stop at the top of the ice pitch, planted both ice axes in the snow, and felt a strange sensation at his back foot. Looking down, he was horrified to find that his boot had come completely out of his binding. Another turn and he might well have found himself doing the fall-and-die thing. Instead, he could at last claim a shared piece of history.

Or so we thought. A few weeks after we got home, Saari sent out a group e-mail. He’d been in the library further researching mountaineering firsts in Peru, and he had some bad news. “I learned that Benoit Chamoux, Eric Favret, and André Genand skied the ‘West Rib’ of Huascarán on June 18, 1983,” he wrote. “This, to me, sounds like exactly the line that we skied which we are calling ‘The Shield.’ Oh well.”

A week later, there was another message from Saari. “I personally think [the Frenchmen] skied the same line we did, but we did ski down the actual Shield, and the West Rib route could have stayed skier’s right the whole time, a much less exposed route. I would not claim our descent as a first though, and I hate shit like ‘first American descent,’ or ‘first snowboard descent.’ I guess in the end it really does not matter. The line was steep, aesthetic, and high. A classic hard route for sure.”