What’s up, dog? Danny Kass, doing his best to keep a low profile slopside in Stratton

What’s up, dog? Danny Kass, doing his best to keep a low profile slopside in Stratton “Sometimes I kinda forget where I am,” says Powers.

“Sometimes I kinda forget where I am,” says Powers. White light, white heat: A competitor surfs above the halfpipe

White light, white heat: A competitor surfs above the halfpipe Kass meets his public.

Kass meets his public. The indestructible Lelly Clark

The indestructible Lelly Clark

Grenade posse in full effect

Grenade posse in full effect Luke Mitrani

Luke Mitrani Fashion-forward at the open

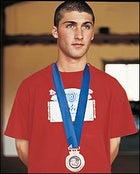

Fashion-forward at the open Does this metal make me look phat? Danny and J.J. (below) get ready for their Wheaties shoot.

Does this metal make me look phat? Danny and J.J. (below) get ready for their Wheaties shoot.

THE GAUNTLET IS turning ugly. Two lines of blunt-booted snowboarders stretch along the main slope of the Waterville Valley ski area in New Hampshire, and they are unsatisfied with the performances thus far. They express their displeasure by spewing insults and mouthfuls of beer at riders speeding by on their way to the icy, two-story quarterpipe below.

“You guys suck!”

Psssssphplaaaaaafth!

The drill is to charge downslope at the towering ramp and catapult off the top lip into a McTwist, a Rodeo Flip, or some other contortion. Several riders sail 15 feet above the top, gunning for amplitude. But the gauntlet needs more, so it shovels snow into the approach, improvising a jump to up the ante. When some of the competitors simply bunny-hop it, the gauntlet scatters to gather empty Bud cases for fuel and starts a fire that forces riders to jump higher to avoid the flames. A few swerve wide of the trouble altogether, but such behavior undermines the spirit of the moment, and they are booed and called pussies.

This is the fifth annual World Quarterpipe Championships, sponsored by Snowboarder magazine and Red Bull. Competition started around 11:30 this morning when an emcee boomed over the P.A.: “The name of the game is DRUNK!” The vibe feels like Lord of the Flies meets Animal House. On ice.

A few days ago, over in Vermont, Stratton Mountain Resort hosted the 20th Annual U.S. Open Snowboarding Championships—the sport’s most venerated event. For the last five years, Waterville has served as a sort of anti-contest. “World Quarterpipe Championships” would seem to imply: officially sanctioned, lavishly sponsored, widely covered. The event is none of these. Winning it guarantees neither sponsorship incentives nor a place in the record books. What victors receive is smirking admiration from the brethren. Respect. As with so many aspects of snowboarding, the World Quarters is an elaborate goof—with a slightly serious edge.

For instance, two of the judges are newly minted celebrities: Olympic halfpipe gold medalist Ross Powers, looking haggard today after enduring a month of appearances (Letterman, Today, the Daytona 500) and an all-night beer-fest during his homecoming at the Open, and Danny Kass, the lazy-lidded rebel who took silver in Salt Lake.

The peripheral activities, however, almost overshadow the riding. At the moment, a round-faced Vermonter is busy pumping up the pressure of a plastic weed sprayer strapped to his back and squirting the frothy contents (Red Bull and vodka, a.k.a. “liquid crack”) more or less into people’s mouths. Giacomo Kratter, the 19-year-old Italian who finished fourth at the Olympics, wobbles around in tattered fatigues, carrying an issue of Penthouse and playing ventriloquist to a rubber turkey obsessed with the magazine. (“I am durky hunter!”) Nearby, two capitalist hooligans work in tandem with cans of spray paint, one distracting a member of the gauntlet while the other lacquers a large stencil of a grenade—the symbol of Grenade Gloves, Kass’s company—on the victim’s backside. Everyone has a beer cozied into a glove or mitten and bobs loosely to the drum ‘n’ bass beat, compliments of DJ NC-17, who’s hunkered in a slopeside yurt-cum-bong rigged with a thumping sound system.

Powers and Kass and the other judges stand near the end of the gauntlet, a vantage that allows them to assess the style with which riders handle both the harassment and the quarterpipe. They confer about the technical specifics of a trick performed by Teddy Rauh, a 24-year-old from East Dover, Vermont, who works as a logger in the off-season. “Let’s see what he claims,” says Powers, “then we’ll decide whether he makes the finals.”

Powers explains that Rauh, after executing a brassy Backflip Indy over the fire and then flipping everyone the bird, hit the quarterpipe and purposefully did a Tailfish—”which everyone knows is a gay trick.” It looks similar to a Stalefish, which is cool, but if Rauh claims a Stalefish, he’s gone. “We’re trying to judge it fair, you know?” says Powers, who has big blue eyes and a smile that wants to veer off the side of his face. “You gotta put everything into it.”

“Hey, Ross!” someone shouts. “Is that your board?”

Powers pokes his shaved head into the alley and sees his pro-model Burton 158 teetering atop the bonfire. (His old friend Kass snuck off and put it there.)

“Awww, shit, man,” he mutters. Then, more urgently, “I need those bindings!” Without thinking, he lurches into the lane and scrambles up the gauntlet, holding his beer out to the side so as not to spill. Just as he stoops to pluck his board from the fire, Burton teammate Colin Langlois hits the jump full tilt, sucking his knees into his chest and skimming above Powers’s head.

The gauntlet erupts. Powers jerks upright and looks downslope, not quite aware that he’s just missed being decapitated. It’s the best moment of the day—unscripted, acrobatic, and a bit sketchy. Just like snowboarding.

IF YOU DIDN’T KNOW any better, you might assume the pranksterism on display at Waterville validates a certain stereotype of snowboarders as lawless punks. But thanks to the Salt Lake City Olympics, you do know better—don’t you?

When Kelly Clark won the women’s halfpipe event—the first U.S. gold of the Games—and then, the next day, Powers, Kass, and Jarret “J.J.” Thomas became the first Americans to sweep a Winter Olympics podium since 1956, snowboarding was transformed in the public eye from hoodlums’ hobby to serious sport. The many outsiders among the 21 million people watching NBC prime time last February 11 couldn’t help but get what they saw: ethereal athleticism. “Oh! I just enjoyed it, that halfpipe thing,” raved Gordon Hinckley, the 92-year-old president and prophet of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, in USA Today. “It was crazy, to get down and tip upside down and cavort about.”

A month later, at the U.S. Open, riders could already sense the bizarre 180 in pop culture perceptions. But broad acceptance ushers in a different dynamic. Without a negative stereotype to gleefully buck against, snowboarders may find it more difficult to define themselves. “We’re a little more respected, for sure,” Josh Pekuri told me while standing at the bottom of the halfpipe during a lull in practice. A 23-year-old engineer on leave from Coast Guard duty, he was wearing a leather skullcap, a Stanley Kowalski undershirt, and a studded leather belt to hold up his snowboard pants. Taking a drag from his Camel Light, he frowned. “People used to look at us like we were all drug addicts.”

Leading up to Salt Lake, all you heard was that top halfpipers hardly cared about the Olympics. They were too cool, the thinking went, to rah-rah such a mainstream event. In fact, core snowboarders had reason to be wary: Events at Nagano in 1998 had made them look silly. The uniforms were dorky, the pipe was shoddy, and the U.S. Ski and Snowboard Association (USSA) mortified them by marketing Animal, the Muppet character, as their mascot. And then, when Canadian Ross Rebagliati tested positive for marijuana, the press wrote off the entire sport as a stoner joke.

The SLC program managed not to embarrass anyone. This time, the best riders were mostly accounted for, the pipe was mint, and the sky was Windex blue. Best of all, the United States dominated. “I was stoked when I figured out that I got the bronze,” says J. J. Thomas, a handsome 21-year-old Coloradan sponsored by Ride Snowboards and Oakley. “But I wasn’t that stoked, because I didn’t have my best run. Then some guy came up to us and told us about the sweep thing—that’s when I got excited.”

But not everyone was stoked. Within the sanctified walls of Burton Snowboards, which puts on the U.S. Open, the posture toward the Olympics remains more bullheaded than bullish. A month to the day after the sweep, the company fired off a sniffy press release that read: “Many people have a false impression, supported by ambiguous communications from the U.S. Ski and Snowboard Association, that America’s snowboarding success is a result of the USSA’s ÔU.S. Snowboard Team’ efforts. This is not the case. . . . The best athletes train, compete, choose sponsors, and manage their careers as they choose—as individuals. The team system does not work, and is essentially a marketing device for USSA.”

It came across as something of a head scratcher, like a grouchy surfer getting territorial over an epic swell. Why bring everybody down when there’s more than enough booty to go around? Perhaps because with a 30 percent stake in the snowboarding market—which last year amounted to more than $100 million in sales—the 25-year-old company considers itself the feisty ombudsman of snowboarding, bent on protecting the sport’s image.

“The number of opportunities for people to talk about snowboarding and fuck it up is just enormous now,” says David Schriber, 38, who was senior vice-president of marketing at Burton for five years before taking over a sister brand, Gravis footwear, last spring. “The growth is consistent with where we’ve wanted to take things, but you have to be careful. We have the job of growing Burton and making it cooler. But bigger is lamer in snowboarding.”

Jake Burton himself seems unworried about the mainstreaming of the sport. “Obviously, for self-interested business reasons, but also beyond that, I think the more people who snowboard the better,” says the 48-year-old entrepreneur, who owns his company outright and rides more than 100 days a year. “What kids are doing—the rails that they’re hitting and the jumps they’re going off—that’s a completely different sport than what mainstream snowboarders are doing. I mean, does Michael Jordan get pissed off that fat white guys play basketball? I don’t think he’s like, ÔDamn, that’s the end of my sport.’ And I don’t think core riders feel that way either.”

Probably true. Definitely true: Snowboarders are nothing if not fickle. Now that the mainstream has latched on to snowboarding itself, can the sport keep its cool?

FOR A GOOD BAROMETRIC reading of snowboarding, rewind to the U.S. Open. Today is Thursday, and people have been practicing on Stratton’s slopes since Monday for the contests this weekend. There are three categories of competition this year: quarterpipe, halfpipe, and slopestyle. Compared with what will transpire at the World Quarters next week, the Open seems tame. Used to be that you could spot riders toking up before a run, hear a member of the Wu-Tang Clan lay down an impromptu rap, or maybe get hit in the head with a beer bottle. Now there’s a $180,000 purse, heavy competition, bleachers, grandparents, and a 25-member private security force. The chaos is under control.

Sort of. Luke Mitrani and Tommy Emanuelson huddle behind the vinyl start tent of the slopestyle event, occupied with how to wear their ski-racerish number bibs in any manner but the official one. Earlier, Luke and Tommy told me they were 21-year-old Texans who’d won the Olympics; in fact, I’ll learn, both were born in 1990 and hail from Vermont. Presently, Luke dishes up some MC trash talk: “We’re the cool rappers/And we don’t like snappers…”

All right. What he doesn’t mention is that he and his four-foot-tall friend are sponsored by two of the sport’s largest companies, Burton and Oakley; that they won every U.S.A. Snowboarding Association halfpipe and slopestyle contest in their respective regions this season (Luke rules southern Vermont, Tommy northern); and that 12-year-old Luke just beat out 135 older pros to make the halfpipe quarterfinals.

But they still have to wear these lame red spandex bibs like everyone else. Tommy, whose blond bowl cut frames a set of cheeks still chubby with baby fat, steps his bulky boots through the bib’s arm holes and hikes the hem up high, peering over his fists to see how he might secure it around his scrawny chest. Luke tries to help, but the thing won’t stay up. Older pros mill around, waxing boards and waiting to take a run. As J. J. Thomas sideslips down the start ramp, two guys in the tent who are not yet 20 compare notes on the orthopedic corsets they had to wear after breaking their pelvises last season. Out back, Josh Pekuri yanks against his own bib. “I feel like a Baywatch girl,” he complains.

All Tommy can manage is a sort of sumo diaper. Not cool. Luke, who has faint freckles and coarse curls, suggests they tie the bibs into do-rags. Yeah! They take off their helmets and goggles and try the Axl Rose approach. Too much material to knot. But Luke has a creative breakthrough.

“Tommy!” he shouts. “We don’t even need to tie it—your helmet will hold it on.” Jamming helmets over headwear, they size each other up.

“That looks sick, dude,” Luke chirps, snapping his goggles into place. Then they strap into their bindings, point their boards downslope, and ride.

“YOU JUST PLAY EVERY DAY,” says Norwegian Anne Molin Kongsgaard, laying out the life of a professional snowboarder over some fries in the Stratton cafeteria. The 25-year-old Burton rider switched from two planks to one in 1994 for the independence it affords—mainly, no coaches telling her what to do. Once they score sponsorships, most pros shelve school and hit the contest circuit sans chaperon. And most, like Kongsgaard, relish the lifestyle of riding, seeing the world on someone else’s tab, and hanging out with a tight group of good-looking friends. Still, it takes stamina.

Take a look at Ross Powers. He arrives midday, straight off a red-eye from L.A. Last night he taped a segment of Weakest Link; today he’s just hoping to get in a few runs. Wearing three days’ stubble and bright yellow goggles, the champ wanders along a carnivalesque main street of sponsors’ kiosks, the tail of his board dragging in the slush, as a huckster for Right Guard Xtreme bellows into a too-loud speaker, “Who’s the most EXTREME here!?”

“It seems like every other night I wake up in a different place these days,” Powers mumbles, looking at his feet. He hasn’t ridden in weeks. “Sometimes I kinda forget where I am, and then I realize what I’m there for and it brings the memory back.”

Powers, who is 23, grew up eight miles away, in South Londonderry, and the Open is his homecoming. People around here are proud of him, and they all seem to know his story: that his father left when he was five, and that he and his younger brother, Trevor, were raised in a two-room apartment by their mom, Nancy, who still works at the Bromley Mountain Ski Resort cafeteria. Ross started racing in 1988, when he was nine, nursing used equipment and winning like mad. Burton took note and started outfitting him the next year. By 1993 he’d made enough of a name for himself to get into the tony Stratton Mountain School ski academy on a partial scholarship, washing windows in the summer to offset his share of the balance. (Tuition is currently $17,300 for day students.) The year after he graduated, he took the bronze medal in the halfpipe at Nagano.

“If it wasn’t for my mom and a lot of other people,” he tells me matter-of-factly, “I wouldn’t be where I am today.”

That place is somewhere over the million-dollar rainbow, according to his agent, Peter Carlisle, who, as director of the action sports division of the management firm Octagon, also manages Kelly Clark, the 19-year-old from Vermont who rides for Burton. Powers was doing just fine with Burton and Polo RLX as his sponsors, but since the Olympics he’s added Stratton Mountain and Malibu Boats (he’s into wakeboarding) to his portfolio. “My guess—and it’s an educated guess—is that he’s the best-compensated snowboarder out there,” says Carlisle.

How Powers goes about making his money is a delicate matter. Selling out is a heavy subject in snowboarding—credibility means everything. Humble as his beginnings were, Powers has to be vigilant about the pitfalls of success. “There’s some stuff you just can’t do because it would make you look stupid,” he says. Like? “They wanted Danny and J. J. and me to go and rock out with ‘N Sync while they were at the Olympics. We didn’t do that. It would probably hurt our image more than help us.”

The new Olympians are acutely aware of the fine line they must walk. “Before the Olympics I would pick up on people saying little things about selling out,” says Clark. “But now that I did well, everyone’s like, ‘Oh, no, it’s totally cool!’ Which is, like, maybe a little bit annoying to me? I don’t want to sell out, you know, and I don’t think I will. But I don’t even know what the real definition of it is. I guess what it comes down to is how you’re going to feel having that sticker on your board.”

The sticker that Powers, Kass, and Thomas will be sporting this season is large and reads Nestea cool. Coca-Cola aired a commercial for its new tea last spring showcasing the three Olympians and a snowman using only the word dude to express various sentiments. It bombed in snowboard circles. “Let me see if I can be diplomatic about this,” says Schriber, Burton’s former image maker, who resembles an ornery, bespectacled Alfred E. Neuman. “What I would hope for is that when somebody wants to use snowboarding to sell their product, they contribute rather than detract.”

That’s a tall order. Dudespeak aside, snowboarders judge coolness in widely varying degrees, so for a major corporation to use the medalists’ credibility without simultaneously eroding it would be lucky. Fortunately for sponsors, the medalists all have different images, which broadens their potential demographic appeal. Powers is the Horatio Alger, Kass is the Willy Wonka, Thomas is the Hunk, and Clark is the Role Model (she did 40 public appearances in the ten days following her victory). “It’s like a perfect Venn diagram,” says Schriber, referring to the kind of graph that employs overlapping circles to illustrate logical relationships. “It’s almost too lucky that three totally different guys got medals. They have three different followings in the sport. All three of them now have to give the Olympics themselves some credit.”

Thomas has no problem with that, especially given that he didn’t expect to be in this position. He posted good but not stellar results until last January, when he finally mastered the Cab 900 and the Switch McTwist, taking first and third at Grand Prix events at his home mountain in Breckenridge, Colorado. Then he won the X Games. “It’s been cool—you get a lot of stuff for free,” says Thomas, who is six feet tall, with a tan to match his medal, and still lives at home with his parents. “You go into the local deli and they’re like, ‘Here you go!’ Tom Petty came to Red Rocks, and I just called my friends over at the radio station in Denver and they hooked me up.” As for the Nestea commercial? “If you go out, people will tease you and shit,” he says. “The only people who really harsh you are just, like, haters—they’re just jealous or whatever. I don’t even sweat that, man.”

Whether the Nestea deal is a first step toward Team Sweep being perceived as sellouts remains to be seen. Kass, for one, entertained other options. According to Bob Klein, his primary agent, he turned down Pepsi’s Mountain Dew, a brand that’s gone after generations X and Y with TV commercials and its sponsorship of the X Games, to sign with Coke’s Nestea Cool.

“When I laid it out to Danny,” says Klein, 38, a Northern Californian who used to be Shaun Palmer’s agent, “I said, ‘Here’s Mountain Dew and here’s Coke. Mountain Dew’s paying about a third more. What do you think?’ He was like, ‘Well, I’m going to do the Coke deal.’ I couldn’t believe it, because I’m thinking Mountain Dew is a no-brainer, the image is already there. Shit, Nestea Cool? C’mon man, there is no image, right? I was like, ‘Why?’ He said, ‘Because I don’t want to Do the Dew—dude.’ That’s all he said. And that’s all it took for me to understand what he was saying. And that, my friend, is what the kids of snowboarding understand.”

DURING OPEN WEEK IN MARCH, Danny Kass is conspicuously absent from the Stratton bars, his usual stomping grounds. “I don’t really have an ID,” he explains when I finally get him on the phone two months later. Of the four medalists, he has been the hardest to nail down. No rider straddles the divide between the underground and the mainstream with as much craftiness as this 20-year-old Jersey kid with the black mop of hair. When asked by a buddy with a video camera at Salt Lake what he was going to do after winning the silver medal, Kass responded, “Dude, I am gonna smoke the fattest…” Then, spotting a Newsweek reporter, he said to his friend: “Dude, nice try! You almost got me, man! Drugs are bad!”

Kass’s credibility is rooted in ability. In the 2000-2001 season, at age 18, the Gnu-sponsored rider won the X Games, the U.S. Open, and three of four USSA Grand Prix events. At the Olympics, where the judging system weighed amplitude more than rotational prowess, Powers won because, in addition to doing some tough tricks, he pulled off what was instantly recognized as the highest flight in halfpipe history—17 to 18 feet of big air. (Riders can go even bigger off a tall quarterpipe, because they have several hundred yards to pick up speed.) Kass, who grew up skateboarding and only started snowboarding at 12, took the other route. He pulled off a Cab 1080 with a Melon Grab (three full rotations midflight, front hand grabbing the heel edge of the board) and landed with enough speed to throw a 900 off the opposite wall—hands down the trickiest sequence that day. The final results had some core riders grousing, because they view Powers as a “pipe robot,” the antithesis of Kass.

“It’s rare to find style like that in snowboarders these days,” says veteran Shaun Palmer, 34, who stormed the circuit with a punk attitude a decade ago. “I mean, people rip—they go 12 feet high—but they don’t look like Danny when they’re doing it.” Then he clarifies: “Danny’s style is style.”

The other reason that adolescent rippers admire Kass has to do with the mystique of Grenade Gloves, the company owned by Danny and his 24-year-old brother, Matt, who both now live in Mammoth Lakes, California. Grenade’s following has almost nothing to do with handwear, and everything to do with the commercial knavery employed by the Kasses and their posse of guerrilla marketeers.

When Grenade logos first cropped up around Mammoth in fall 2000, nobody knew if the company was real. Matt had made the design, a friend hit on the idea of using stencils and spray paint, and the crew started tagging. But there was no product yet. Then, in February 2001, at the Grand Prix in Mammoth, an NBC cameraman was tagged, and a certain giddiness infected the circuit. Kids with no firm affiliation to Grenade bought their own paint and entered the game to see how far they could spread the virus. When the gloves finally did hit shops in November 2001, all 6,500 pairs sold. To date, Grenade has sold roughly 15,000 pairs at $40 to $80 a pop; combined with T-shirts, sweatshirts, and hats, that amounts to just under $1 million in sales in 2002.

“We’re not like your average new company that gets millions of dollars thrown in for advertising,” explains Danny. “We just started spray-painting everything and everybody, instead of buying $20,000 ads in Maxim. We’d spray-paint big posters of Patrick Swayze and use them as signs. It was just cooler, you know? Nothing else gets marketed like that.”

Grenade exudes cool in a way that even Burton can’t replicate—though it’s not above trying. This fall, Burton introduced a board called the Dominant, which has a plain white deck and comes with stencils so you can paint your own design.

“Personally, I think Grenade has helped revitalize the sport of snowboarding,” says Carter Olcott, 27, Burton’s North American team assistant. “They are so not the corporate way that snowboarding has maybe become over the past five years. Once the big money started coming in, [riders] started getting a lot more focused and not going out one or two nights before the contests. One of the coolest things about the Grenade crew is that they went out and partied harder than anyone, and still came in and won. It made me go, ‘Shit, man.’ That shows that you’re an amazing athlete. You don’t necessarily need to drink Gatorade 24 hours a day.”

The suggestion that snowboarders don’t survive on sports drinks alone has caused Kass some consternation. Several weeks after the Olympics, he returned to his hometown of Vernon, New Jersey, for a small contest and a break from the media attention. Journalists dispatched to the scene needed quotes from the silver medalist, but he made himself unavailable. One reporter from Sports Illustrated, Yi-Wyn Yen, pressed for an interview; Kass said no. But the matter did not end there.

“She just kept badgering me,” says Kass. “I was wondering what I could get her to do, so I tried to get her to buy me a keg. I figured she wouldn’t be able to write the article at all—it’d be dicey. Then she went and got all this beer with my friend, and wrote in the article how, like, we went and got all the beer.”

The March 18 article dubbed Kass “snowboarding’s most notorious bad boy” but failed to disclose that it was the reporter who purchased the “nine cases of Bud Light, four cases of Corona, and two cases of Coors Light” for the underage snowboarder. (“We are aware of the situation and it has been handled internally,” said S.I. spokesman Rick McCabe. “It is contrary to our standards for securing interviews and developing relationships with sources.”)

“It was kind of a prank,” Kass tells me. “I thought it would be humorous for a Sports Illustrated person to purchase a bunch of minors alcohol to do an interview with them. But I mean, they loved it, you know? They just made us sound even worse.”

THE HALFPIPE IS NOT something found in nature. Building one requires pushing some 882,000 cubic feet of snow into place and then sculpting it into a 500-foot-long U-shaped gully that measures 56 feet across from lip to lip. Though the pipe at the U.S. Open is only 425 feet long and a degree steeper than the current standard—there wasn’t enough snow—it’s still what’s known as a “superpipe,” thanks to its depth: 18 feet from the lip to the bottom of the trough. (Salt Lake had a superpipe as well, but the Nagano halfpipe measured a comparatively wimpy 12 feet deep.)

When you drop over the lip of a superpipe, crouch low over your board to rip across the belly of the beast, then push against centrifugal force and zip up the opposite wall, you can blast 15 feet or so above the top. Reentry, however, is risky: If you don’t return along the same vertical plane in which you took off, you’ll either land on the deck (just above the lip), or free-fall several stories to the pipe’s flat interior and blow a knee or two.

At the halfpipe finals on Saturday, Luke and Tommy warm up a crowd of 5,000 standing three deep along the decks. On the last trick of his exhibition run, Tommy lofts above the lip, throws an arm back like a bronc rider, and . . . gooses his crotch with his other hand. The crowd lets out a collective war whoop.

At the end of the pipe, goggled and toqued spectators shoot digital video footage, shout the favorites’ names, and pump their arms at big-air tricks. The music—a mix of hip-hop and metal—is stifling, forcing the announcer to shout his observations. Such as: “Tricia Byrnes, folks, won this contest ten years ago! She’s also the publisher of Eastern Edge magazine—and not to mention a college graduate!!”

Ten men and ten women make the finals, and they “jam” together in a kind of utopian antiformat. They take as many runs as they can in one hour, after which they’re ranked on overall “impression.” It’s willfully vague, and ends up looking like a friendly melee.

Giacomo Kratter, the Italian turkey ventriloquist, loses his hat and goggles in a high-flying spin. Fans reach over to high-five him as he trudges back up along the bannered barricades. Then American Keir Dillon pendulums down the pipe, vanishes from view, and explodes above the lip right in front of Kratter’s face. Kratter nods approval—nice one—as Dillon jets overhead, barrel-rolls sideways, and disappears back into the pipe.

Finland’s Markku Koski caps a run by spinning a 1260—or maybe it’s a 1440. Nobody’s sure which, including Koski, who shrugs when the announcer shouts, “Markku, what was that?”

Next, Kelly Clark loops her way down and catches an edge on a backside 540, smacking her chin hard against the snow. She doesn’t move at first, and the announcer lowers the volume when Clark fails to give an acknowledging wave. Tricia Byrnes, hiking back up after her own run, dumps her board and jumps into the pipe like an airline passenger hitting the evacuation slide. Clark starts moving, slowly, and after ski patrollers arrive to check if she’s OK, she heads back up for more. Which isn’t too surprising. Clark has ridden all season with a torn meniscus in her right knee; the day before her Olympic win, she broke her wrist. “It sounds really bad,” she tells me later, “but that’s kind of what I’m known for.” She’ll end up winning the halfpipe contest, and pocket $20,000.

Powers goes pretty big, but he looks rough around the edges. His friends have shown him no mercy since he’s been home; the day he arrived on the red-eye, he was up until 6 a.m. with visitors to his hotel room, and he rode the semifinals with no practice. “I was just happy to qualify,” he says afterward.

Meanwhile, Kass seems to be finding a groove after crashing on his first few runs. He drops in and does a huge, straight air, casually grabbing his board as he floats above the pipe, and slips back in like he’s easing into a velvet sofa. Then he slices—fast—to the other side for an inverted 1080, shoots back across, and jacks himself above the lip for yet another 1080. He finishes with a 720 and a goofy little nose tap, but that’s gravy. He’s just pulled off something he’s never done, not even in practice: back-to-back 1080s. “It was always in the back of my head, but I had never really landed the frontside 1080,” Kass later says of the combination, a half rotation better than his Salt Lake performance. “I tried to play it safe a little bit at the Olympics, but at the Open everyone was stepping it up so much.”

Dillon finishes third and Koski second. At the awards ceremony, Kass is announced as the winner and he meanders through the crowd toting a Grenade poster that reads we must exploit. buy-sell-buy-sell-buy, his army helmet shading his eyes. After the obligatory champagne shower, Kass hops off the stage and shambles over to a fence restraining hundreds of fans. He starts signing autographs.

“Danny, Danny, could you hook me up with your goggles and write your name across them?” shouts one teenager.

“Dude, I’m going to ride with them,” says Kass.

“Let’s go partying and drink some beers, Danny!”

“Yeeeeaaaaaah,” he responds, reaching out for a shirt that needs ink.

“CanIhaveyourhat, Danny? Danny, canIhaveyourhat?”

“Hey, Danny, say a little something for me, go ahead,” says a kid wedged up front, training a digital camcorder on Kass.

“What’s up, dog?” he obliges.

Thick clouds settle overhead, sending a chill through Kass’s slack five-foot-five frame. He wears a sweated-out T-shirt, and his bare arms are splotchy and goose-bumped, his cheeks red. He’s been at it for 20 minutes when a friend behind the clot of kids yells in a Beatlemania soprano, “Hey, DAN-ny!” Kass looks up and an insulated bomber jacket lands over his head. It’s his.

“Dude,” he mutters in thanks. He slips it on and says quietly, “I gotta go over here,” then walks over to a group of younger kids who haven’t been able to get to him. The bad boy of snowboarding stays for another 15 minutes or so, until nearly everyone is gone.

THREE DAYS LATER, over at the World Quarters in Waterville, all the beer’s been drunk and the bonfire’s been put out and Shane Flood, a 23-year-old rider from Rhode Island, has been judged the winner. (Rauh took second.) Powers and one of his oldest friends, Frank Knaack, return to the Best Inn in Plymouth, New Hampshire, which is housing all the riders who have migrated from Stratton to Waterville. As they pull in, they’re greeted by eight police cars parked helter-skelter in front of the motel. The desk clerk is going door to door with a police escort, kicking out anyone who could pass for a snowboarder. “All ah you guys are pissin’ on the walls, pissin’ on people’s caahs, throwin’ beeah cans,” she announces. “I can’t be playin’ favorites; everyone’s gotta go.”

It’s a fitting wrap—and the end of an era. The World Quarterpipe Championships as we know it won’t exist this coming season. The folks at Snowboarder are moving it to a ski area near Boston. “We’re going to sell out,” says senior editor Pat Bridges, a 29-year-old with a husky voice and build who’s fond of aviator sunglasses. “We’re going to do it up, put on a real stadium event.” The plan is to bring in bleachers and bands, and—because they won’t be tucked away in the New Hampshire woods—focus more on competition. There will even be prize money.

“How many years can you keep it real without paying the price?” Bridges asks. “It’s weird, you know. Somebody’s living in a cardboard box in a ski area parking lot, but they’re keeping it real? It’s like, C’mon, man, it’s big business now. We’ve done [the World Quarters at Waterville] five years in a row with no lift tickets, no entry fees, no release forms—and that opens everybody involved up to a lawsuit.”

Thomas hopes to be there. When I speak to him in late August, he tells me he’s been spending time playing golf and rehabilitating from ACL surgery on his right knee, which he blew just before the finals at the U.S. Open. He is excited about his post-Olympic windfall: He scored a character in Activision’s new Shaun Palmer’s Pro Snowboarder 2 video game, his own pro model from Ride (for which athletes receive somewhere between $10 and $20 for each board sold), and a sponsorship deal from Right Guard Xtreme Sport deodorant. “Hey, everybody’s got to wear deodorant,” says his agent, Todd Hahn.

Kass’s stock has risen as well. He’s looking at an economic boost that will take his earnings from $250,000 in 2002 to nearly half a million in 2003. No wonder he whiled away his summer playing video games and riding at Mount Hood, where he was filmed for a new Grenade 16mm release called Full Metal Edges. Clark, ever the go-getter, went surfing in Costa Rica in May, won an ESPY award for action sports athlete of the year in July, and did a lot of training at Hood.

When not traveling for corporate appearances, Powers has been hanging out on Cape Cod with his mother and grandfather and trying to get some work done on his house—an old cob job on 126 acres about half a mile from Stratton that he and his friends gutted and are refurbishing. He’s had offers to subdivide the land, which he bought three years ago for $208,000, but he’s not interested. Better to have your own motocross track. “Snowboarding’s pretty much been my life,” he says, “and now to be able to make a living and be kinda secure in doing something that I love to do—it’s awesome.”

As for the sport’s biggest player, at press time Burton Snowboards was in talks with none other than its old rival, the USSA, about a deal to outfit the U.S. Snowboard Team.

This season, all of the medalists plan to do more slopestyle events, which may open the door for up-and-coming halfpipe riders. “This is going to be a fun year, because there’s no qualifying for the Olympics,” Thomas says. “We weren’t raised to go to the Olympics. We just love snowboarding.”

That holds true regardless of whether the sport’s image gets hijacked by tone-deaf ad men. As with anything that becomes popular in the mass market, snowboarding can—and will—be accused of selling out. It’s an inevitability. Funny thing is, nobody’s trying to stop it. Do you think Powers, Kass, Thomas, and Clark regret their success? Don’t kid yourself.