Walking the rows of pro skier Chris Rubens’s Revelstoke, B.C., farm with him under a punchy May sun, it’s hard to square the subdued and pensive character before me with the high-octane hero he plays in ski movies.

The first ever images I can recall of him, cut together in Matchstick Productions’ 2006 film Push, showcased an eager newcomer pinning the throttle, throwing 360s off 40-foot cliffs, and beaming at the chance to go heli-skiing—a privilege afforded to him by virtue of having “made it” as a pro.

His segment sold a dream come true: powered by helicopters, snowmobiles, and a super-human dose of gumption.

Eighteen years later, the 39-year-old has all but grown out of that ideology, foregoing the stereotypical trappings of pro skiing for simpler pastures. He travels less, prefers pillows to do-or-die gnar, and does everything he can to keep his carbon footprint low; that includes hardly using helicopters or snowmobiles anymore. And while on its face that sounds like winding down, he is still charging hard, still filming, and, he says, it’s better than ever.

That’s the message at the heart of a career-spanning biopic set to release about the long-tenured star freeskier this fall. Looking back on a filmography propelled by combustion, Rubens’s self-produced new movie seeks to tell his story but also give pro skiers a dream to strive for that isn’t just heli-skiing.

As a guy who helped cement many fossil-fuel-powered shooting techniques that depict the modern sport, that’s no small walk back. Neither is leaving institutions like Matchstick Productions and Blank Collective Films behind to go your own way. But then again, he’s no stranger to fighting the current.

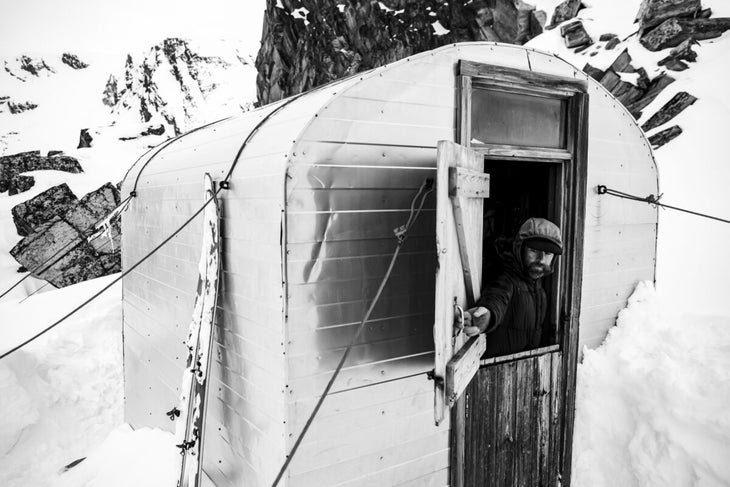

Rubens was instrumental in persuading Matchstick to start shooting at ski-touring lodges 15 years ago, opening up an entirely new mode of ski-movie production without helicopters. In the wake of that revolution, he also had a big hand in developing sturdy ski-touring gear like the .

More recently, he revamped the ski into an ultra-light, super playful freeride ski that also charges. He likewise popularized expedition skiing in movies like Sherpas Cinema’s ALL I CAN and in many short films by Salomon TV, in which he tested himself in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco and the Himalaya, amongst other locales. But throughout it all, healso did a lot of snowmobile and heli-skiing.

“It seemed like the prerequisite to being a pro freerider was you had to have a sled,” he recalls. “It was either that or heli-skiing. And heli-skiing you’d blow your whole season’s budget in two weeks.”

He and childhood friend Eric Hjorleifson, who opened pro-skiing’s door to Rubens, spent many seasons flailing together on their machines as they learned and eventually mastered them. That made Rubens one of the pre-eminent athletes of his day—he could go anywhere and do anything. It was a position that afforded him a status worthy of more and more heli-skiing trips from sponsors and film companies, which was the goal of any pro skier back then, as he tells it.

“It was exciting, there’s no doubt about it,” he says.

Though he was aware of the effects of fossil fuels (modern two-stroke snowmobiles emit about five times more carbon per mile than the average car and spit unburned oil into the snowpack), work was work. And this was how work was done.

“Until that point I was like most people,” he admits. “I wasn’t a climate denier, but it was such a big problem I was like, ‘How am I going to do anything about it?’”

Putting that aside, he steadily rose to the ranks of the world’s most filmed and famous freeskiers. Then came a 2016 trip to Greenland with Salomon TV for the short film Guilt Trip, in which he and other pro skiers help a climate scientist collect glacier core samples. The film is a lighthearted soliloquy about adventure skiing loosely pivoting around the issue of climate change, but it mostly takes advantage of the destination as a setting. When it went on tour to New York and Toronto, skeptical audiences saw through it.

“They were like, “So, what are you doing about [climate change]?’ And we were like, ‘Well, we made this movie.’ And I was standing on a stage, and I wasn’t prepared for that. I felt like a fraud,” he says. “So I was like, ‘OK, if I’m going to talk about this stuff I need to walk the walk. And I need to have some tangible things that I’ve done.’”

He leaned into his ski-mountaineering skill set, which he realized was a tool as good as any helicopter. Many of his Salomon TV trips from that point began to bear a self-powered ethic and focus on story. There was a road trip to ski volcanoes in the Pacific Northwest in an early electric car and then a traverse of the Monashee Mountains’ Gold Range that helped reveal a new way forward.

This was around the same time fellow Revelstoke was also making an environmental transformation, giving Rubens someone to collaborate with. Eventually, Rubens started dating Hill’s younger sister, Jesse, a fiercely intelligent woman with a degree in environmental science and lots of ideas. One of them was to start an organic farm to fight food insecurity as the climate shifts. She and Rubens did just that during the pandemic, and the ever-expanding farm is thriving today.

“I’m an old skier but a young farmer,” he likes to joke.

The decision to have a kid, though, was a little harder. As he and Jesse watched the glaciers around them shrink, winters become wetter, summers drier and more choked with wildfire smoke, they wondered what kind of world a child would grow up in.

“We’re going into year three of a serious drought in British Columbia,” he tells me soberly. “And I really thought we were sheltered from a lot of the effects of climate change here. We’re in a rainforest and it feels like we’re growing in a semi-arid desert now.”

But, as happens, a child came nonetheless. Huxley’s arrival further solidified the need for even more action, prompting Dad to double down and work harder to make a better future. It also made Rubens reflect on his influence on current and future generations.

“Back in the day when we would go to a trailhead [by snowmobile], it was just film crews. You go to the trailheads now and they are absolutely packed with everybody because we showed how rad it is,” he says. “I think when you’re younger, and someone’s giving you money to go skiing, you’re just like, ‘Holy, I can’t believe they’re paying me to do this sport, this is the sickest thing ever!’ And you don’t realize how much influence you have, per se.”

As to whether this film is an all-out correction on those images, Rubens says he doesn’t like to think of it that way—he’s not big on regrets. He just wants to show a different way forward now.

“You can still achieve crazy lines and push your ski limits and also be a little kinder to the Earth,” he insists. “I’m not trying to make the world’s best ski movie, but I am trying to showcase that foot-powered skiing is really fun and attainable. It’s not a struggle, it’s fun. I can still remember every ski-mountaineering line I’ve done to this day; I can’t remember all the heli lines.”

Shot and directed by longtime collaborator is clear-headed about the limits therein. He says if it had been any other athlete, the quality of skiing in the film might not have been equal.

“It was actually really hard,” Bonello explains, “because you hike for three hours just to get to the elevation that you’re going to start shooting at. But Chris is just so dialed on every front. He just knows where the good snow is, knows what’s happening with safety, knows how to get a good shot, knows how a story works. And he has the legs.”

Bonello asserts that, of all the athletes he’s worked with over the years, Rubens has fundamentally changed his life the most according to his values. Even though it’s not easy, working this way is evidently viable for him. Which means it could be for others as well.

“All of this stuff is about going to extremes to prove that something isn’t as impossible as everybody makes out,” Bonello continues. “Whether that’s jumping off a 100-foot cliff or ski touring to everything.”

For Rubens, there’s one more dimension to that. “It’s an opportunity to focus on what you want people to take away from your career,” he explains. “Were you just a model, or did you have something to say?”

Rubens and Bonello’s yet-to-be-titled film will be released online this fall, presented by Picture Organic Clothing, Atomic Skis, Tourism Revelstoke, and Revelstoke Mountain Resort.