THE DEVIL BEAT HIS WIFE FOR 20 MINUTES as we passed through sugar-beet fields a handful of highway miles east of Bliss, Idaho. That’s bus parlance for a sun shower, frosted flakes of snow flitting through a sunbeam as we dieseled northward, away from Utah’s icing rain. All right, folks, this is Bliss. We’ll be taking a half-hour dinner break here. If you’re not back on the bus in half an hour, make sure you have enough money in your pocket for breakfast. “Piss in Bliss,” say the Hound-hardened. We filed off the bus, and I did.

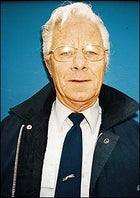

Greyhound driver Al Douglas calls the shots from Calgary to the U.S. boarder.

Greyhound driver Al Douglas calls the shots from Calgary to the U.S. boarder. The depot in Roseburg, Oregon.

The depot in Roseburg, Oregon. Tunnel vision: Rolling toward Banff, Alberta, on the snowy Trans-Canada Highway

Tunnel vision: Rolling toward Banff, Alberta, on the snowy Trans-Canada Highway

Sleeping it off on the road to Walla Walla

Sleeping it off on the road to Walla Walla Snow-bound: The powder piles up near Revelstoke, B.C.

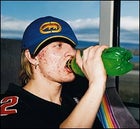

Snow-bound: The powder piles up near Revelstoke, B.C. Breakfast on the Greyhound Motel: Mountain dew, french fries, truck-stop coffee, and thou

Breakfast on the Greyhound Motel: Mountain dew, french fries, truck-stop coffee, and thou Pendleton, Oregon: If you’re not back in 15 minutes, make sure you’ve got money for your next meal.

Pendleton, Oregon: If you’re not back in 15 minutes, make sure you’ve got money for your next meal.

I’d started this trip in Ogden, Utah, the Peoria of the West, a dinged-edge ski town, the finest city in Utah, and, not incidentally, a quintessential Greyhound town. My wife, Hilary, and dog, Daisy, kissed me good-bye. Daisy hates bus stations, as they tend to steal me away for weeks at a time; Hilary’s more used to them. Loaded for a three-week-long journey that could be harder than the hubs of hell, I’d fortified myself with coffee and a dog-eared paperback of On the Road. On page 24, Mississippi Gene tells Sal Paradise this about Ogden: “‘It’s the place where most of the boys pass thu and always meet there; you’re liable to see anybody there.'” This day, there was only a doughy guy in a flannel shirt and mussed hair, sprawled facedown across a hard sectional bench, a little pool of drool on the floor underneath his face.

“Hey, you can’t sleep here!” the desk clerk hollered from behind her computer monitor. “This is a place of business.” He started, springing sort of upright. “I ain’t sleepin’,” he said.

“Well, you can’t,” she said. “What is that?” she asked as she handed me a baggage tag.

Skis, I told her.

“I thought so.”

This was as thorough as the security check got; I may’ve had a pair of 200-cm bazookas in there. She trusted me. Or didn’t care. Didn’t even ask my name. “Just show your pass to the driver.”

I was armed with a $324 Domestic Westcoast Can-Am Discovery Pass and a pair of telemark boards—Evolution U-2s, 200’s, as long and heavy and American as the Dog itself. For weeks I had pored over the Greyhound route map and my old Wal-Mart atlas that showed ski areas marked with little salmon-hued schussers and tiny letters: Hoodoo Ski Area. Marmot Basin. Mount Lemmon. Not resorts, with their après scenes and shiny airport shuttles, but their Greyhound equivalents. I wanted to see the West from the window of the bus, not in a light of desperation, but rather as a ticket to some of the best hidden skiing in North America.

Keep this in mind: Rock stars take the bus. Country music stars do for sure. Think Willie Nelson and “On the Road Again.” Greyhound was born in 1914 in Hibbing, Minnesota, hometown to one Bobby Zimmerman—a.k.a. Bob Dylan. Still, a stigma hounds the bus, and an unfair one at that. I know extreme skiers who huck cliffs and sleep in a tent for days in winter who cringe at the Hound; I know war correspondents who refuse to go Greyhound. Like many people, I used to associate the bus with low points in my life. Once, as a kid, I looked up from watching Dragnet on one of those dime-fed fuzzy televisions in the downtown St. Louis depot and saw a police officer shoot a man in the hand. But today, at the onset of the 21st century, the bus is refreshing when compared with the strictures of air travel: No one with a little dog sewn on his chest will pat you down or make you take off your shoes—they just ask that you smoke 100 feet away from the diesel tank while they refuel.

The Portland-bound nooner, coach number 6022, wheeled into Ogden with a hiss of air brakes 27 minutes late. “What is this?” the driver asked. Discovery Pass, I said. “Is that what this is? I only see these in summer.” The Portland-bound smelled of people who’ve slept in the same clothes for days and longer. Folks living on truck-stop hash and 7-Eleven burritos. Make it me: I am part of this great unwashed.

I found a seat, stowed my daypack full of licorice and sandwiches, fixed my Gore-Tex shell against the mystery stains and communal detritus, then looked through the smoked glass at the parking lot. Hilary stood waving me off in the rain.

It confused my ski friends that I was going Greyhound. It confused my Greyhound friends that I was going skiing.

WHAT I LIKE MOST ABOUT THE BUS is its potential energy. For less than the price of a Goodwill hide-a-bed, I can go whichever way the wind blows, wherever the snow is falling. My own 48,000-pound, 55-seat SUV. Greyhound serves nearly 4,000 destinations in the United States and Canada; one Greyhound bus removes, on average, 17 cars (or SUVs) from the road. Literal miles per gallon, one bus driver told me: seven to ten. Passenger miles per gallon, based on a full bus: 162. Last year the Hound ran nearly eight billion passenger miles. Five thousand of those were mine.

I spent 200 hours on the bus or in bus stations. I tried to line up sofas throughout my figure-eight route, Ogden northwest to Boise, and on to Washington State, then north to British Columbia, east to Alberta, back down to Vancouver, and south to Oregon, California, and Nevada. If conditions—snow—allowed, I figured I’d go all the way to Arizona and New Mexico before rounding the corner home. Alas, I became aware that there are vast voids in North America where I don’t know a soul. I got good at sleeping on the Greyhound Motel.

First stop, Boise. We rolled into town and I could see the lights of Bogus Basin shining like a Jetsonesque city in the sky. A friend from high school, Jolyn, picked me up. “You look like you could use a beer,” she said. I could. The next day we drove up to Bogus, the road winding below the highland estate of potato magnate J.R. Simplot. J.R.’s biography title says it all: A Billion the Hard Way.

Bogus Basin is a Gem State jewel. What the little areas lack in high-speed quads and apres swank they make up for with zero attitude and a season pass for 200 bucks. Places where every liftie knows your name and, for a six-pack, they’ll let your dog on the chair. There’s a place like that called Pine Creek near my home in Wyoming; until last year it still ran a low-speed single chair for the in-bounds runs, and a rope tow to access the backcountry. It’s a BYOB scene, which is just fine with the locals.

In Idaho, nine-to-four lift hours are for wimps. By four o’clock, having dropped all 1,800 vertical Bogus feet, we were just getting warmed up for the real start of the day—night skiing. Minivans full of grommets and their parents began stacking up in the parking lot. School’s out, work’s over, time for an Idaho Friday night. A hundred sixty-five acres of terrain lit up with first-rate mercury vapor lights. People sang and laughed and skied right up to the T-Bar, which was packed with ruddy-cheeked schussers drinking heartily because they didn’t have to catch a chair tomorrow until the crack of 1 p.m. If you like, $37 gets you 13 hours of lift-serviced skidding at Bogus. But I needed a few hours of shut-eye before I had to catch the 6:20 a.m. Portland-bound.

THERE IS SOMETHING PRIMAL about Greyhound. Airlines do not name themselves after animals. The baggage man in Boise said he didn’t know why the Portland-bound was 45 minutes late. Yes, drivers carry cell phones, but, he explained, there’s a lot of country out there that’s out of range: “He’s out there on his own.”

How a passenger company that never asks your name, understands that you may not possess current ID, and doesn’t usually care to look at your luggage knows the following is a mystery, but Greyhound corporate claims that “almost 20% of Greyhound passengers make more than $50,000 per year.” In La Grande, Oregon, we took on a slight, blond woman in tight jeans and a black leather jacket. She was tattooed and pretty, in a vodka-pickled sort of way, and instantly gained an audience in the aft half of the bus, explaining through much profanity and stretching how she’d been a gymnastics instructor for 11 years. On full buses, coteries form, and this gal was a leader.

As in prison, cigarettes are currency on the Hound. The sun is up when we pull into an Arby’s, and a round man with a chaste mustache and a tubercular cough—Hardy of Laurel and Hardy— waddles in for a cup of coffee, using the 15-minute stop to smoke with much animation. I watch as a younger man, would-be Laurel, asks for a cigarette. There’s a twinkle in Hardy’s eye. He pulls out a fag and, just as the young man tries to grab it, it’s rescinded. This happens several times—seagulls jostling over a cheese puff—to Hardy’s glee. Finally he lets Laurel have it, but the driver herds everyone back on the bus. Hardy walks the gauntlet to his seat. “Gooood morning, everybody. Good morning. Good morning.” Hardy is an ambassador of the Hound.

Scrappy Pendleton, Oregon, off #6576 to Portland, onto #6063 to Pasco with a stop in Walla Walla. Our new driver wore the fuzzy hat of a gulag guard, standard Greyhound issue. The snow blew in curtains; we drove with chains. Once again, it was just me de-busing; the lonesome skier shoulders his boards in Walla Walla. Humping my gear to the parking lot, I knocked the yellow plastic Western Union sign off the ticket window with my skis. The clerk reached for the phone; I hitched my pants and vamoosed.

The pride of Dayton, Washington, is Bluewood, a Lilliputian nonresort with Brobdingnagian tree skiing. The next morning I caught a ride at Starbucks with Jesse, Erik, and Adam, three students from Walla Walla’s Whitman College. These kids are all serious Bluewood season-pass holders. I told them what I was up to, wayfaring through winter, skiing places like this. “You ride the Greyhound,” Adam said, “you’ve earned your trip.”

These kids know they’ve got a good thing in Bluewood, a Northwest secret, but they weren’t worried about my spoiling it. “The thing about Blue is there’s no way to get here,” Erik said. The summit, at 5,670 feet, is relatively low, but the area lies under the path of Pacific-fueled storms that drop in and stay for dinner. In the parking lot, we booted up and hopped the shuttle: an honest-to-Jack Frost sleigh. Max and Jake, the local Percherons, let us off at the ancient triple, which spews diesel and smells like a bus station. Even though the eight inches of new was quickly heading toward a foot of fresh, the locals weren’t in any hurry. There are never more skiers than Max and Jake can keep up with.

The three amigos showed me their hidden stashes: openings in the thick spruce of the Umatilla National Forest, homegrown runs with no names except Country Road and Champagne off Country Road. We’d lay fresh tracks, rest them for a run, then return to find our ruts filled. I kept an eye out for Bigfoot. On the chair the kids talked of term papers; on the slopes they took me to school. It came down all afternoon—powder sweet as a Walla Walla onion. “Hit the taco truck before you leave town,” Jesse advised. “Taco truck is so grub.”

“Weren’t you here yesterday?” asked the bus-station clerk, gluing together the sign incident in her mind as she stamped my pass.

“I don’t think so,” I said.

LADIES AND GENTLEMEN, if you know anything about diesel engines, you know they can’t warm up at idle; they’ve got to work. The coach will warm up here as we get out on the highway. If you’d like me to adjust the temperature later on, please let me know. Greyhound drivers are proud of their equipment. As they should be. Waiting to clear Canadian customs at the Blaine, Washington, I-5 border crossing, our driver, John, doled out the stats. This outfit is a 55-seat MCI G4500, the stretch limo of the Greyhound fleet. It’s got a Detroit Diesel 12.7-liter, 400-horsepower engine that gets better fuel economy than your Hummer H1. Stainless-steel monocoque body, fiberglass and composite exterior skin, air-ride suspension with a manual leveling system.

This was the overnight to Vancouver, where I planned to sleep a couple hours and catch the 5:30 a.m. to seat-of-the-britches-who-knows-where. The beauty was that I had no idea. My pass allowed me all of Alberta and British Columbia. Big country.

The border guard couldn’t understand I was skiing the Hound. “What brings you to Canada on the bus at this hour of night?”

“Skiing.”

“Whistler?”

“Probably not.”

“Where, then?”

“I’m not sure. I have a pass.”

“Do you have a job?”

“Sort of.”

“Welcome to Canada.”

Vancouver at 2:30 a.m. is fuzzy as a homemade tattoo.

They locked me out of the bus station. Literally, the station closes. This was odd, because it’s also the train station. For such a large, beautiful city, this was something I hadn’t expected. “Don’t come back before five,” the guard said. I humped my skis, heading for the brighter lights of downtown, and, I hoped, a Tim Hortons coffee shop where I could cool my heels.

Pacific Central Station sits in the Lapland of Chinatown and Hastings Street, western Canada’s largest crack- and heroin-trafficking district. The weather oscillated between rain and wet snow, and it was unsettling to hike, 70-pound pack and skis over my shoulder, down streets lined with strung-out zombies, strip clubs, and pawnshops. I decided to find a shadow in the park in front of the bus station and wait it out.

At 5 a.m., when the guards unlocked the doors, young people with snowboards and daypacks queued up for the 5:30 to Whistler. I boarded the Nanaimo, Vancouver Island-bound instead, and woke an hour later to find the bus, me inside it, in the belly of the whale, the ferry, with driving rain outside.

The bus was nearly empty. Up front there was an island resident who had taken the bus all the way from Los Angeles and a guy dressed like a lumberjack who was on his way to a blind rendezvous with a woman he’d met in the personals. The two talked about dog breeding for more than an hour. The driver let the lumberjack-on-the-make off at an unscheduled stop along the coast. There were no other tourists.

I liked the idea of skiing an island. And if it weren’t for the thick clouds, I probably could have seen the ocean from the 5,215-foot summit of Mount Washington. That’s what the locals said, anyway. The shuttle from Courtenay to Mount Washington, a big little resort, the un-Whistler, is an antique school bus. Most of the passengers were lodge employees, and the bus mood was festive. It snows here often—Pacific systems that sometimes last for days—350 inches a year. When it doesn’t snow, like the day I arrived, the slopes are harder than hell, but by midmorning the ice had softened. I caught Linton’s Loop and traversed over to the Sunrise Chair, where I skied Sunrise till sundown. In Greyhound aprs-ski fashion, the two Canadian lagers I’d stashed to cool in a vacant lot near the Courtenay station were waiting for me. Island life: ski, booze, Greyhound, snooze.

The driver from Courtenay to Nanaimo was named Earl. He wore a gray wool uniform and a chin beard, Gregory Peck in John Huston’s Moby Dick. The lumberjack stood at the highway waving his arms—the dog breeder, finished with his romantic weekend. Apparently it had gone well; she blew him a kiss.

IT IS IMPORTANT NOT TO DRINK ALCOHOL on the bus. I learned this from my friend Fly-Fishing Bob, who was once left in the Utah desert because he thought he could sneak a 3 a.m. brewski. Psssssssstchchchch! He was gone. It is also important not to board the bus buzzed. I routinely saw passengers bounced before their trip began. The driver has the power of a sea captain, and you are at his mercy.

It’s like being on a boat: Sleeping on the bus, waking, hitching a ride up to the hill, buying a lift ticket, being pulleyed up the mountain, skiing down, the payoff, the magical dancing of linked telemark turns, the floating sensation of skiing down. Repeat. Back on the bus and moving on. You become uncomfortably aware of stasis—standing roadside with your thumb out, waiting in Seattle for a three-hour layover, sleeping in an Alberta hostel. Your fluids are still in motion. Call it the Greyhound Powderhound Wanderlust. To wake up stationary becomes strange.

Canadian Greyhound drivers are all frustrated Zamboni pilots and they don’t slow for weather. Several times we actually passed snowplows. But I slept in the quiet of snow, my trust in the driver. In deep REM through Hope, Golden, and on to Lake Louise; I was sorely disappointed to have arrived. I went without coffee. I dozed off again on the shuttle from Banff to Sunshine Village, where an Australian ski tuner named Steve offered to watch my pack all day: “No worries, mate.”

Unless you’re Richie Rich, Sunshine Village isn’t exactly a mom-and-pop hill—three mountains, a thousand acres each—but the snow is world-class. I felt a little guilty throwing down $37 for a lift ticket that could, on the bus, take me from Rock Springs, Wyoming, to Reno. But, hey, these are Canadian dollars, eh?

And today is Big Dump Day at the ballpark! I skied three feet of light and dry—first the Garbage Chutes off Standish, then over to Goat’s Eye for Big Woody and Goatsucker Glade. Whoop, whoop, whoop. It dumped all day and an avalanche cut off the road back to town. All several thousand of us were stranded. There was a last-minute party at someone’s house, me and every young person from Australia drinking Molson Canadian until they quickly ran out. Even that was fun. The Aussies were smoking high-quality B.C. bud and waxing their snowboards with hydrocarbon Swix and a clothes iron.

“Greyhound is a shitty way to see Australia,” one said through the fog.

“It’s a rock-and-roll limousine in Canada,” I told him. “They showed Pretty Woman.”

WHEN MAKING TURNS with good people in good snow, the bus seems far away. I was back in the USA now, at the rough end of the pineapple. Unlike in spiffy Canada, each bus in America has a different mood, a different smell. Sometimes the bus smelled like french fries. Cigarette smoke in clothing. A hint of marijuana. Often the bus smelled foul. Diapers, hangover breath, body odor. I had coffee and mustard stains on my pants, bearing grease on my parka from old chairlift guide wheels. Greasy bibs. Greasy hair, which I kept under my hat. I washed my polypropylene underwear in a sink when I could. Road food. Often the bad smells on the bus came from me.

When your reading light works, it’s like winning the door prize—a little victory, a beam from heaven. This truck stop has a Quizno’s? I’m a king!

We had trouble in Salem, Oregon: A well-dressed African-American gentleman (the only passenger in 5,000 miles who wore a tie) approached the driver. I figured he wanted off at an unscheduled stop, but he was complaining about being harassed by a skinhead, who was blaring his skinhead music from enormous headphones that he aimed at this man’s seat. That was it. The driver stopped the bus, called the police. Salem’s finest pulled the skinhead off, cuffed him, and stuffed him in the back of the patrol car. The gentleman stepped back on, and we were on the road again. Ashland is a flag stop along the interstate. The driver dumped my skis in the dark and revved off to California. “Where’s the town?” I asked the only other passenger getting off here. He pointed to more darkness.

“About two miles,” he said.

“Thanks.”

I built up a good sweat. I could see the lights of Mount Ashland above me. I crested a hill into a residential area, and there was the lighted front porch of the Ashland Hostel. Welcome, traveler. Within moments I was sitting in front of a fire, talking telemark with new friends Jardin and Cody. For 18 bucks I had a bunk. The dreadlocked commune of the hostel is, curiously, a lot like the community on the bus. The hostelfarians were all veterans of the Green Turtle, the Furthur-like merry prankster outfit that trucks lazily up and down the Left Coast.

I skied Mount Ashland with two locals, Tom and Felicia. The three of us had the entire weekday mountain to ourselves, and there isn’t a friendlier mom-and-pop in winter. When I broke the weld on my left SuperLoop toepiece—these bindings had been a vale of tears from the start—Doug, head of the ski patrol, tried to fix them, and when he couldn’t, the rental shop comped me a pair of bondage boards and boots to match. From the top of Mount Ashland, I could see Mount Shasta. To the southwest I could make out the tiny interstate convenience store that’s also the Ashland bus stop. A military jet blew over. It occurred to me just how ephemeral flight is. These diesels will go on forever.

ANY WAY THE WIND BLOWS. I could have gone south to L.A. and missed Tahoe and good skiing. I couldn’t go through Denver—too many days on the bus. If I’d bought the 30-day I could have made it, but I was running out of money and calendar days. So I headed for Nevada, one big-ass state away from home.

I changed buses in Sacramento. Super Bowl Sunday. There was a snowboarder and a young lady with a boot bag headed for South Lake Tahoe. A man who looked like he’d stepped out of a seventies-era Camel ad with a burly mud-colored dog. Everyone else seemed Reno-bound. We dropped off of Donner Pass, doglegged past Truckee, and it’s the lights of Reno, baby! You’re either a Vegas or a Reno fan, but you can’t be both. I love Reno for what it isn’t: Vegas. Reno is the bastard calf of Nevada gambling towns, a secret ski town with breakfast buffets and showgirls. The Mount Rose shuttle picks skiers up at the Sands, and I ate eggs across from two hookers getting off the graveyard shift.

I found out, talking on the pay phone under the Western Union sign in the Reno bus depot, that I was going to be a father. I missed my wife, my dog, even Opie, the cat. An altercation broke out in the middle of the depot—Camel guy from Sacramento and the swing-shift security guard, Leon, taking it outside. “Gotta go, sweetheart. Call ya back. Love you, bye.” Five minutes later Leon waddled back in, gesturing, it would seem, to everyone in the depot. “Tell you somethin’: Blind, my ass. And that ain’t no guide dog!”

Next stop, Ogden, where I’d started. I stayed on till Logan and hitched up Logan Canyon to Beaver Mountain—the Beave, my favorite little area in all of Utah, the best ski state in the country. The manager, a guy named Travis, loaned me his Salomons mounted up with pin bindings. I bought a ticket—$25—and jumped Harry’s Dream, the antique double. Harry’s is electric now; they sold the original diesel motor to a potato farmer—keep the french fries coming.

It hadn’t snowed in several days, and I had a hoot making high-speed turns on the vacant groomers, talking flies and fish with Nick, the chief liftie, who works summers in Alaska. Nate, the snowcat mechanic, gave me a ride over the pass to the Chevron in Garden City in his ancient Ford, its hefty exhaust leak filling the cab with fumes. I stood outside in the minus-10-degree cold and caught another ride, this time from my friend Karla, headed for home. I was back to where my world is small. Heater on high, Barenaked Ladies on the stereo.

If they’re on the road, the other Greyhound powder bums, I did not cross paths with them. Neither had any of the drivers I talked with. But the bus is a frontier, like the early days of telemarking, and the route map is the only limit. Perhaps mine was something of a first ascent with the Hound, I don’t know. It doesn’t matter. What’s important to me is that it’s possible, even practical, to ski the big white elephant from the Hound. And that a mountainous infrastructure is ready and waiting for a developing powder nation dieseling through the night.