Julia Mancuso

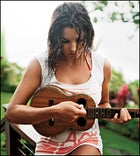

SHAPED SKIER: Giant-Slalom gold medalist and ukulele plucker Julia Mancuso

SHAPED SKIER: Giant-Slalom gold medalist and ukulele plucker Julia MancusoJULIA MANCUSO JUST LEAPT off a 45-foot waterfall. Now she’s treading clear blue water below, trying to convince me to follow. “Jump hard and tuck your arms and extend your legs before you hit,” she calls up. I don’t think so. “I’ll just walk around,” I yell back, scanning the jungle for an escape.

“This is the only way out,” she says. “But don’t worryÔÇöit’s easy!”

So far, nothing about my day on Maui’s north shore with Mancuso, 23-year-old phenom of the U.S. Ski Team and part-time Maui resident, has been easy. We started with a hair-raising drive in her pickup along the switchbacks and single-lane bridges on the road to Hana. Then it was a punishing slog up what locals call the Commando HikeÔÇöa shallow river littered with felled trees and one very puffy feral-pig carcassÔÇöand into a pitch-black lava cave full of deep pools. “This is where we put on our war paint,” she said, smearing mud on her cheeks after we’d swum across the third pool. “Why?” I asked. “Are we going to war?” Mancuso grinned, then led me up a 20-foot free climb to the cave’s exit and halfway across a wooden suspension bridge, where we jumped 25 feet back into the river before reaching my current point of no return, at the top of the waterfall.

“Just do what I do in the starting gate,” she shouts, trying to coach me over the edge. “Clear your mind, take a deep breath, and go.”

This ritual has sure worked for Mancuso of late. At the 2006 Olympics, in Turin, she took a deep breath at the top of the giant slalom and went from longshot to gold medalist. She followed that with a breakout performance on last year’s World Cup circuitÔÇöfour wins, ten podium finishes, and third place overallÔÇöwhile recovering from surgery to remove a painful bone spur on her left hip. This year, she’s favored to become the first U.S. woman to win the overall World Cup title since Tamara McKinney, 25 years ago. But even if she does that, she’ll still be only halfway to her goal: Ultimately, she wants to be seen not just as a skier but as an icon of the year-round adventure lifestyleÔÇöthink Laird Hamilton in a bikiniÔÇöwhose marketability extends far beyond the slopes.

Me? I just want to get off this waterfall. After ten minutes of whining, I jump. But in the air I freak out and ball my legs into my chest andÔÇösmack!ÔÇö hit the water painfully like an oblong coconut. Mancuso can’t stop laughing. “See?” she says. “Easy!”

MOST AMERICANS CARE about ski racing exactly once every four years, which is why it takes a standout performance at the Olympics to build a career. Picabo Street (silver in ’94, gold in ’98) and Tommy Moe (silver and gold in ’94) parlayed their success into lucrative endorsements and, in the case of Moe, a heli-ski operation in Alaska. Mancuso hasn’t been as lucky. Going into Turin, the U.S. squad was expected to dominate. Instead, team poster boy Bode Miller guzzled … well, you know that story … while Mancuso and Ted LigetyÔÇöwho won the team’s only other medal, a gold in the combinedÔÇöbecame asterisks to a meltdown.

If people do remember anything about Mancuso from the Games, it’s probably her clashes with Street, who retired in 2002 but remains the grande dame of American skiing. The two had been bitter rivals since 1999, for reasons that are debated but may have something to do with the fact that at one point Street’s boyfriend was also Mancuso’s full-time ski technician and traveling partner. The day before the start of the women’s giant slalom in Turin, during an interview on the Today show, Street lashed out at Mancuso for racing the earlier slalom event in a plastic tiara, a gag gift from coaches who affectionately refer to Mancuso as “Princess.”

“She has a lot of growing up to do,” Street told Matt Lauer. “And lose the tiara.”

Mancuso’s response? On a foggy morning with wet snow fallingÔÇöstandard conditions back in Lake Tahoe, where Mancuso grew upÔÇöshe beat the second-place finisher, Finland’s Tanja Poutiainen, by nearly a second. The result was instant celebrity in EuropeÔÇöwhere ski racers rank with soccer players in sports notorietyÔÇöand comparisons to tennis’s Maria Sharapova. “She’s beautiful and an outstanding skier,” says Patrick Riml, coach of the U.S. Women’s Ski Team. “She’s a star over there.”

Of course, being huge in Europe doesn’t always translate stateside (see Hasselhoff, David), and Mancuso feels frustrated by her lack of recognition here, despite sponsorship deals with POC helmets, Rossignol, and Tamarack Lodge that pushed her 2007 income into the seven figures. “At the Olympics, the eyes weren’t really focused on me,” Mancuso says. “So, even though I won, I was a little disappointed. I learned that it’s not really anybody else’s job to promote me. I need to take it into my own hands.”

And she has. Last winter, Mancuso started a blog, Kiss My Tiara, where she chronicles her island-girl fitness routineÔÇösurfing, paddleboarding, kiteboarding, road biking, and weight liftingÔÇöand posts chatty reports on her vacations, U.S. Ski Team news, and random topics. You can find it on her homepage, JuliaMancuso.net, directly below a prominent link to her new Lange Girl posterÔÇöa ski-boot ad featuring Mancuso wearing what appears, under my careful scrutiny, to be eight square inches of red laceÔÇöand ski boots.

It may seem like an aggressive strategy for a skier, but Mancuso is convinced that she needs to transcend her sport if she’s ever going to become an enduring name-brand female athlete like Sharapova or Amanda Beard. “I want to show everyone that what I’m doing is a complete lifestyle,” she says. “I can be a female athlete and still be beautiful.”

Two days after my waterfall flop, I’m beginning to think Mancuso’s idea of getting her name out there means, in some twisted way, beating the shit out of writers. I’m straddling a six-foot surfboard in the lineup at Thousand Peaks, my backside now a deep purple. “Paddle, paddle, paddle!” Mancuso shouts from her paddleboard as a good-looking swell approaches. “Now stand up!”

I do, briefly, then splash into the Pacific for the tenth time. She mercifully trades boards with me and snaps up on the next wave, then crouches low and rides all the way down the line, raising her fists as she nears the shore. She looks like she’s just won another gold medal.

MY LAST NIGHT IN MAUI, Julia’s father, Ciro Mancuso, is holding court over lamb and Chianti at the beachfront home he shares with his second wife, Katie, and their four-year-old daughter, Taly. “I could’ve died out there!” exclaims the 59-year-old developer, who has graying hair but a thirty-something physique. He’s telling dinner guests about his hairy paddleboarding experience a few days ago on his daughter’s board. “I was by myself, without a leash, hit by a swell and fell off,” he continues. “And 40-knot winds blew the board away. So I let it go and swam two hours to shore.” (They found the board a few days later.)

It’s clear where Mancuso got her passion for sports and risk, but her dad is also one reason Mancuso may never be totally happy about the way she’s portrayed in the American media. In 1989, Ciro was showering inside his family’s 6,000-square-foot Lake Tahoe home when a team of FBI agents stormed in and arrested him. He was the brains behind one of the largest marijuana cartels in U.S. history, which had smuggled some 45 tons of pot (worth roughly $98 million) into the country. His sentence, after he agreed to testify against his former lawyer, was four years in a federal prison in South Dakota. “He went to jail when I was in kindergarten,” Julia says. “When I’d see him, it was behind plate glass. His going to prison was one of the reasons I grasped on to skiing.” And after she won her medal, it stole the headlines.

But for tonight, at least, that all feels like history. “You know, Ciro,” I say as he refills my glass, “Julia told me that paddleboarding story a little differently. She said, ‘Dad almost lost my new board!’ “

Julia chuckles and says, “It’s OK to laugh, since he’s still here.” Then she sits back and throws her arm around her father. For the first time since I arrived, Julia is at rest. And I feel safe.