HIGH ON A GLACIER in Austria’s Ötztal Alps, a dozen ski racers waited at the start of the Sölden giant-slalom course. It was mid-October, and the ski gods had blessed Sölden with crisp nights and daytime rays that made the mountain feel like California in July. At the start gate, Swiss, Finnish, Slovenian, and Austrian skiers stretched and checked their boots with great seriousness. The 2005–06 World Cup opener was a little more than a week away, and this was one of their few chances to ski the course prior to the race.

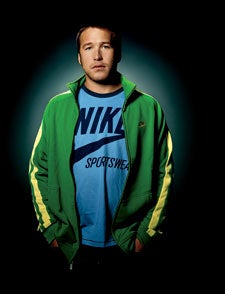

Bode Miller

HISTORICALLY GREAT: Bode Miller at Copper Mountain, Colorado, November 2005.

HISTORICALLY GREAT: Bode Miller at Copper Mountain, Colorado, November 2005.Ted Ligety

THE WUNDERKIND: Slalom phenom Ted Ligety

THE WUNDERKIND: Slalom phenom Ted LigetyErik Schlopy

THE VETERAN: Giant-slalom ace Erik Schlopy

THE VETERAN: Giant-slalom ace Erik SchlopyPhil McNichol

THE DRILL SERGEANT: Men's head coach Phil McNichol

THE DRILL SERGEANT: Men's head coach Phil McNicholJesse Hunt

THE STEADY HAND: U.S. men’s and women’s alpine director Jesse Hunt

THE STEADY HAND: U.S. men’s and women’s alpine director Jesse HuntJulia Mancuso

PERPETUAL THREAT: U.S. women’s all-rounder Julia Mancuso

PERPETUAL THREAT: U.S. women’s all-rounder Julia MancusoDaron Rahlves

THE SPEEDSTER: Downhill champ Daron Rahlves

THE SPEEDSTER: Downhill champ Daron RahlvesBode Miller

THE MAVERICK: World Cup overall winner Bode Miller

THE MAVERICK: World Cup overall winner Bode Miller“Wooo-hooo!”

Out of the blue, some joker gunned it up the side of the start ramp and went for big air. He spun and stuck his landing behind a cluster of Slovenians.

“Did you see that?” he said, grinning like an idiot. “Sweet 360 safety grab.”

Oh, yeah: The Americans were there, too.

The freestyle trickster was Ted Ligety, a 21-year-old slalom wunderkind on the U.S. men’s ski team. With his spiky blond hair and cocky grin, Ligety’s like a one-man frat party. He sidled up to Daron Rahlves, the 32-year-old American downhiller. Rahlves noticed Ligety’s eyewear. “Nice goggles,” he told the kid. “Thought you were a chick.”

Ligety lifted his hot-pink Uvex frames. “Hey, man, pink’s the heisse scheiss,” he said. “The chicks dig it.” Only one year on the World Cup tour and Ligety could already say “hot shit” in German.

This was the American men’s alpine ski team four months before the 20th Winter Olympic Games, in Turin, Italy: loose, fun-loving, and confident. Coming into Turin, the Americans find themselves the odds-on favorites to end Austria’s decade of skiing dominance—or at least crash the party in style. Last year, Bode Miller, the 28-year-old New Hampshire phenom known for his maverick behavior and outspoken opinions, won the overall World Cup title and became the first American man since Phil Mahre to hold the World Cup’s crystal globe, given to the best ski racer on the planet.

With a new autobiography, Bode: Go Fast, Be Good, Have Fun, in stores and a Nike ad campaign set to blitz the tube during the Olympics, Miller has become the ubiquitous almond-eyed face of American ski racing. When he first made the team, in 1996, Miller recalls, “Tommy Moe and AJ Kitt had a couple wins in the speed events”—downhill and super-G are considered “speed” events, slalom and giant slalom (GS) “technical” races (for more details, see ““)—”but on the tech side, there wasn’t anybody doing anything.”

You can’t say that anymore. Miller has been dominating the technical events, reaching the podium in slalom or GS 29 times in the past six years. And he isn’t alone. Rahlves, the downhill superstar from California who’s been coming on strong in other disciplines, finished fifth overall in the 2004–05 World Cup, trailing only Miller and Austrians Benjamin Raich, Hermann Maier, and Michael Walchhofer.

In early December, at the Birds of Prey World Cup, in Beaver Creek, Colorado, the U.S. men’s team notched its best performance in the history of American ski racing. Rahlves and Miller took gold and silver, respectively, in the downhill. The following day Miller won the GS, Rahlves placed second, and veteran Erik Schlopy took fourth, just a hundredth of a second short of third. On the last day of the event, Ted Ligety won bronze in the slalom, a career best. Meanwhile, up in Lake Louise, Alberta, where the women were racing in their second World Cup of the season, Lindsey Kildow took gold in the downhill. By the end of the weekend, it was the Americans who had become the ones to beat.

It was not always thus. Eight years ago, the American men were the Bad News Bears of ski racing. (The women’s team, buoyed by Picabo Street, Hilary Lindh, and Kristina Koznick never sank so low, despite their disappointing Olympic-medal shutout at Salt Lake in 2002.) World Cup SL and GS races are like golf tournaments; there’s a cut after the first run. Only the 30 fastest racers, out of a starting field of about 75, bib up for the final run (SG and DH hold only one run). In the late nineties, the American men weren’t just finishing out of the money—they rarely took a second run. Between 1996 and 1998, the editors of Ski Racing had such a hard time finding an American man to name Skier of the Year that they declined to award the prize.

What changed? A lot, and the changes have created high hopes for this year’s Winter Games, generating plenty of advance hype. Nike is positioning Miller as the poster child of the Olympics. 60 Minutes was scheduled to air a Miller profile in December. As early as November, members of the men’s and women’s team visited Matt Lauer on the Today show to tout their prospects at Turin.

“The resurgence of the alpine program will be one of the top stories of these games,” says Peter Diamond, a senior vice president of programming at NBC. Last summer, Diamond told a gathering of U.S. skiing officials that alpine events would get featured in prime-time slots—especially with charismatic athletes like Miller, Rahlves & Co. “You aren’t going to see the men’s downhill on at 2 a.m.,” he said.

The rise of the U.S. men’s team from nearly worst to nearly first is a tale of motivation, self-reflection, espionage, and the high art of logistical mastery. The Yanks have spent years not just training one great skier but turning the whole system into a well-oiled machine. From the CEO to the head coaches to the iron-scarred technicians in the waxing room, they’ll all tell you that American ski racing is finally earning something it hasn’t known for most of a decade: respect.

That respect was on display last fall in Sölden. One day I watched Chip Knight, 31, an American slalom racer who’s been on the team for 13 years (equalling only Rahlves’s tenure), slide into the starting gate. He dug his poles into the snow and angled his upper body over the starting wand.

“What’s the fastest split so far?” Knight asked.

“D-money,” said trainer Paul Meier, referring to Rahlves. “Thirteen-zero.”

Knight kicked out of the gate and charged down the course. Next came Ligety, and then Rahlves. As soon as they went, six Austrian course technicians swarmed the starting gate. They indicated to Meier that the Americans’ time was up. The Austrians had reserved the hill space for 11:30. It was now 11:32.

Meier stood his ground. “D’s gonna get one more run,” he said.

The Austrians wouldn’t hear it. “No more,” one of them told Meier. “Finito.” The Austrians are the New York Yankees of skiing: They have more money than anyone else, and they have more trophies than anyone else. They’re used to getting their way. Meier folded his arms.

“Who ees?” the Austrian asked.

“Daron,” said Meier.

“Daron?” said the Austrian. He paused and reconsidered. “OK,” he said. “Daron, one more.”

TO FIND OUT HOW THE TEAM had come so far, I went to Park City, Utah, last July to meet Bill Marolt, 62, CEO and president of the U.S. Ski and Snowboard Association (USSA), which manages several Olympic snow sports, including alpine skiing, cross-country, freestyle, nordic combined, and snowboarding. No one has been more instrumental in rebuilding America’s ski-racing program—raising money, improving coaching, and streamlining the racer-development system—than Marolt.

An Olympian and, in 1963, national downhill champion himself, Marolt was the team’s alpine director in the late seventies and early eighties. His tenure coincided with a golden age in American ski racing, when Phil and Steve Mahre, Tamara McKinney, and Bill Johnson gave the Europeans all they could handle. In 1984, Marolt left to become athletic director at the University of Colorado, where he watched his head football coach, Bill McCartney, take the Buffaloes from a 1-10 record in 1984 to a national championship in 1990.

It was Marolt’s success at Boulder, combined with his ski-racing pedigree, that convinced the USSA board he could save their sinking ship. The nineties were dismal years for skiing in America. The sport lost the cachet it had enjoyed since the seventies. Snowboarding became hip. Skiing became that thing your parents did. From 1992 to 1999, snowboarding grew from 1.6 million to 3.6 million riders, while skiing lost nearly one-third of its 10.8 million participants.

As the ski business struggled along, the U.S. Ski Team’s budget, supported largely by corporate and private donations, steadily eroded. Promising junior racers drifted into snowboarding or the sexier and more lucrative world of freeskiing. On the World Cup circuit, the Americans were getting lapped. The team made do on a bare-bones budget, trundling up icy mountain roads packed ten to a van while European superstars like Alberto Tomba zoomed by in Ferraris. At one point, money got so tight that the team asked the athletes to chip in to cover travel expenses. A string of CEOs—three in three years—seemed powerless to stop ski racing’s decline.

That changed with Marolt. In the spring of 1997, shortly after he took the helm, he gathered the USSA’s top officials in a conference room at the group’s Park City headquarters. The USSA needed a clear mission, Marolt told them. “[Colorado football coach] Bill McCartney always talked about goal setting and focus,” Marolt went on. “He’d say you’re not really committed to a goal unless you’re willing to write it down and put it up on the wall.”

Marolt uncapped a pen and wrote four words on a sheet of paper: best in the world. He tacked the sheet to the wall. “This,” he said, “is what we want to be.”

Marolt pounded goal setting into the USSA’s corporate culture. Coaches and athletes were expected to lay out goals for every season, every training session, every race. He laid out his own list: Stop the revolving door that sent old coaches out and new coaches in every year; reconstruct the talent pipeline, which meant reconnecting with some 350 amateur ski clubs around the country; and create sophisticated sports-medicine and training programs from scratch. Above all, he needed to build up the organization’s financial foundation, the key to achieving his aims.

Marolt reached into the pockets of both corporate America and the nation’s wealthy skiers. I happened to be in Park City while he was hosting the USSA’s annual Partners Summit at the Canyons Resort. I sat in as Marolt, a tan, trim, and perpetually upbeat figure, presented his “best in the world” pitch—now much closer to reality—to a conference room full of financial backers.

“We have the men’s overall World Cup champion, Bode Miller,” he said. “Our women’s team will challenge the Austrians. We’ll come into the Torino Games as the biggest single story on the U.S. Olympic Team.”

Representatives from Chevrolet, United Airlines, Tommy Hilfiger, Visa, and other brands nodded approvingly. In eight years, Marolt has more than doubled the USSA’s budget to $19 million.

Marolt also touched on other alpine stars. Behind Miller and Rahlves stand hard-charging youngsters like Ligety, the defending U.S. slalom champion, and Jimmy Cochran, 24, who finished 16th in GS at last year’s world championships. (On the World Cup, the top 20 spots are often decided by tenths or hundredths of a second, meaning top-20 finishers are all within reach of a medal.)

Other promising young guns include GS specialist Dane Spencer, 28, who’s finished in the top 15 six times in the past three years, and downhiller Bryon Friedman, 25, who cracked the World Cup top ten twice last year before a broken leg curtailed his season. Among the veterans, Erik Schlopy, 33, won bronze in GS at the 2003 world championships (held every two years and separate from the World Cup), while his recent fourth-place at Beaver Creek was his best World Cup result since then.

The women’s side is also stocked with standouts, including speed skier Lindsey Kildow, 21, four-event standout Julia Mancuso, 21, young slalom and GS charger Resi Stiegler, 20, tech veteran Kristina Koznick, 30, and slalom specialist Sarah Schleper, 26, who took gold at last year’s World Cup finals. Add downhillers Kirsten Clark, 28, and Jonna Mendes, 26, and the multidiscipline veteran Caroline Lalive, 26, and you find that all the women—with the exception of Stiegler—have nabbed a podium finish on the World Cup. As good as Miller, Rahlves, and the American men are, the women’s team could steal the show in Turin.

After his speech, Marolt went out in the hallway to the breakfast buffet of bagels, pastries, and orange juice. “Hey! Good to see you,” he said to an old friend. He chatted up new acquaintances, inviting them to become USSA partners.

If all goes well, the partners will each pony up sums ranging from a few thousand dollars to several hundred thousand for another year’s sponsorship. Chevrolet, the ski team’s biggest backer, is already in for $2 million. By the end of April, private donors and fundraising events are expected to bring in another $5 million. The money is helping Marolt reach the USSA’s endowment-campaign goal of $60 million, part of which will be used to build a new training center in Park City. More recently, the expanded budget bolstered the team’s sports-science program and helped produce a series of instructional DVDs, which the USSA distributes to regional coaches to better harmonize teaching methods in the farm system.

The revived finances have helped lift the program, if not beyond the Austrians, at least within reach of them—and that will be particularly important at the Winter Olympics. Not many Americans know that Bode Miller won the World Cup last year, but plenty will know if he wins gold in Turin. And in America, where ski racing takes center stage only every four years, that may be all that really matters.

WITH THE MONEY BEGINNING TO FLOW in a positive direction, Marolt needed a coaching staff that could translate bold new ideas into results. One of his goals was to nurture a generation of world-class American coaches. From the late eighties to the late nineties, American ski coaches tended to be either European guns for hire or Americans drafted from another sport. Austrians, Swiss, and Swedes were good people and great coaches, Marolt believed, but their presence sent a troubling message: Americans can’t do this.

Marolt has never promoted nationality over competence—even today, the women’s head coach is an Austrian, Patrick Riml—but coming into Turin, the men’s team has four Americans in the top spots for the first time in at least a decade. Jesse Hunt, a sandy-haired former junior champion from Vermont, now oversees both the men’s and women’s teams as alpine director. Phil McNichol, the men’s head coach, is a straight-talking, hard-knocks skier known for tapping racer potential. Mike Morin, who coaches the tech disciplines, is a quiet, wiry New Hampshire native who started coaching before he even graduated from college. John “Johno” McBride, the charismatic men’s speed coach, grew up in Aspen and roomed with Hunt at the University of Vermont. Morin and McBride bring a yin-yang balance to the team.

“Mike’s the superorganized, uptight one; Johno’s the relaxed, laid-back one,” says Dane Spencer. “And Phil’s kind of in between.”

All four have spent the past 20 years banging around the U.S. racing system—coaching at elite clubs and ski-racing academies and putting in thankless years on the Europa Cup circuit, ski racing’s minor league. By the late nineties, all had worked their way into jobs as assistant coaches with the U.S. team. Tired of watching their racers trip the clock entire seconds behind the Europeans, they started looking for a better way to do business. Around the bar after races, they would ask European coaches why their skiers were faster than the Americans. The Europeans gave it to them straight: Your technique sucks. Your stance is all wrong. You’re out of balance.

“Our guys were out of whack,” Mike Morin told me one afternoon in Sölden. “American racers thought the only way to go fast was to get in a position where your ass was basically sitting on your bindings.”

The coaching staff realized it was time to start over, to rebuild the American racing style from the boots up—and what better way to start than by spying on the Austrians?

No nation in the 39-year history of the World Cup has dominated like the Austrians have in the past decade. At the height of their current run, in 1999, seven of the world’s top ten ski racers were Austrian, and the depth of their team is legendary.

At Sölden, I ran into Walter Delle Karth, Hermann Maier’s press officer. With his long hair and leather jacket, Delle Karth is a familiar, dashing figure at World Cup events. The Austrians were racing one another that day to determine who would compete in the World Cup opener later that month.

“How many of Austria’s top guys are trying to qualify?” I asked.

“Twenty-five,” he said flatly.

After a disastrous 1999 World Cup season—capped by a medal shutout at the world championships, held that year at Beaver Creek—USSA officials offered a deal to the devil. “We went to the Austrians and said, ‘Why don’t you come over and train with us at Beaver Creek, and in exchange we’ll train with you at one of your camps?’ ” recalls Alan Ashley, the USSA athletic director.

Access to Beaver Creek in November was the only card the Americans held. The resort hosts an early World Cup race each year—the lone U.S. stop on the circuit. Prior to 1999, Beaver Creek allowed only the Americans to train on its course before the race. If the Austrians could train there, it would give them a leg up on the rest of the world. The Austrians agreed.

For the next few years, the Americans trained with the Austrians at Beaver Creek, at New Zealand’s Treble Cone resort, and at Portillo, Chile. With may be too strong a word; it wasn’t the chummiest arrangement.

“Sometimes we’d join them for a couple sessions, but we’d get the shitty end of the stick,” recalls Erik Schlopy. “One time we were supposed to train with them at Pitztal,” an Austrian resort. “We went up there but couldn’t find them. They left a note telling us to train at this one spot. It was OK, but it had soft, powdery snow. Later we found out they’d set up on the back side of the mountain with hard injected snow. That happened all the time.”

The Austrians paid little attention to the Americans, who posed no real threat. But the American coaches watched the Austrians closely.

“What opened our eyes was the intensity of their training,” Jesse Hunt told me. The Austrians didn’t waste a minute on the hill; their skiers took fewer runs than the Americans, but they treated every run like it was race day. The night before a training day, the Austrians would inject water into the course with a high-pressure irrigation system. Overnight, it would freeze through, allowing the racers to train on a rock-hard, World Cup–grade surface. Soon the Americans were freezing their courses, too.

Then the Yanks made a crucial psychological breakthrough. During slalom training, the two squads went head to head in time trials. When the Americans came out on top, word spread like wildfire. “I wasn’t even on the team back then and I remember hearing, ‘Bode and Chip beat the Austrians today!'” recalls Bryon Friedman. “Before that, the Austrians were like an unbeatable force. You couldn’t pierce their armor.”

Granted, it was just practice, but the experience of defeating them anywhere showed the Americans that it was possible. Before long they began beating the Austrians for real: In 2001 Daron Rahlves took gold in the super-G at the world championships. Two years later, Rahlves became the second American in history to win the terrifying Hahnenkamm downhill, a major World Cup upset on the Austrians’ home turf. The next season, Bode Miller was beginning to tear up slalom, GS, and combined, collecting six gold medals and the 2003–04 overall GS World Cup title.

Last August, the Austrians wised up. When the Americans traveled to Treble Cone, they discovered that the Austrians had booked the entire resort and had told the manager not to let the Americans on the hill. After some logistical scrambling, the U.S. team found an alternate training site, but the message was clear: Kiss off.

I ONCE ASKED JESSE HUNT if there was a moment when he knew the ski team’s fortunes had finally turned. Edging the Austrians in practice? He shook his head.

“There was never a big bang,” he said. “It’s been a slow progression. What we’ve been able to do with our coaches is create a positive environment for the athletes, to help them reach their goals and have their individual needs satisfied. It’s a positive push, as opposed to a more negative day-to-day battle.”

That battle involved subtle and not so subtle tactics. Through the late nineties and early naughts, gear, technique, and training were evolving dramatically. In 1996, at the Junior Olympics in Sugarloaf, Maine, Bode Miller, then 18, became the first elite racer in the world to compete on shaped skis—short models with an exaggerated hourglass shape. He beat by more than two seconds the silver medalists in GS and super-G, races usually decided by fractions of a second. By the next year, when Miller joined the World Cup circuit, almost all the racers were using the new carving skis.

In a very short time, racers had to adapt to the new, radically shorter skis. Slalom models shrank from an average length of 200 centimeters to 165. “Not since the introduction of hinged gates in the early eighties have skiers adjusted their techniques so much,” Phil McNichol writes in The Professional Skier.

The new skis held an edge better than the old models, which let racers angle their upper bodies more sharply over the centerline of each gate. The parabolic shape forced the skis to arc more—the skis wanted to turn—which meant racers could execute shorter-radius turns simply by rolling the skis on edge with their ankles rather than driving their hips and knees like they used to.

Hunt, McNichol, and the others didn’t just overhaul technique; they changed the very way they coached. Ski racing has a long tradition of old men barking at young men to “Do it the right way!” The new American coaches knew that wouldn’t work.

“European athletes tend to accept that one-way communication,” Hunt told me one afternoon in Park City. “You’re told what to do, and that’s the way it’s going to be. American athletes are less willing to accept that. They need more two-way communication.”

It’s no coincidence that Hunt developed this philosophy as the ski team’s tech coach in the late nineties while dealing with the young Bode Miller, a notoriously “uncoachable” racer. Hunt knew he had to show—not tell—his athletes how technique changes would help them go faster. One tool he employed was video. Hunt was one of the early adopters of Dartfish, a program that can overlay video images so racers can easily compare their own lines with other racers who are getting better results.

“He’d say, ‘This is what you’re doing, and this is what the guys who are winning are doing,’ ” says Morin. “Jesse put up photos, videos, and times in a way that the athletes couldn’t deny.”

In Sölden, I sat in on a video session with Ted Ligety, Morin, and assistant coach Greg Needell. We watched a monitor showing Ligety fly down the hill over and over again.

“Good start,” Morin commented.

“Nice tuck, too,” added Needell. “But you’re lifting your skis off the snow here.”

Ligety deflected the criticism by trying to joke around. “Air’s got less resistance than snow,” he said.

“Unfortunately, that’s not how it works,” said Morin.

“Watch Daron at full speed,” said Needell. He pulled up a clip of Rahlves carving down the same section. The difference was obvious. Rahlves tucked cleanly and kept both skis glued to the snow.

Morin ended Ligety’s video session with a question: “What are your goals for Sölden, Ted?”

Ligety sighed. The athletes don’t often see Bill Marolt face to face, but they deal with his goal-setting edict every week. “Qualify for Sölden,” Ligety said. “Race at Sölden. Place at Sölden.”

“Go home a hero,” said Morin. “I like that.”

THE NEXT DAY up in the queue for the GS course, Ligety was razzing Rahlves about sharing some swag. “D, you gotta get us some of those Oakley ‘phones,” he said.

Ligety and Rahlves provide an object lesson in the brutal economics of ski racing. Rahlves, fifth in the World Cup standings at the end of last season, earns more than $1 million a year from race purses and sponsorships like Oakley. Ligety, who stood in 62nd place at the end of last season, was scraping by. Ligety’s racing suit is emblazoned with ads for Visa and Chevy, but that money all goes to the USSA. The only real estate available to the racers is the front of their helmets. Rahlves’s helmet reads red bull. (It might as well say big money.) In Sölden, Ligety’s helmet also paid homage to his financial sponsors. Scrawled on a piece of tape was mom + dad. (It now reads PARK CITY MOUNTAIN RESORT, a new sponsor attracted by Ligety’s recent strong results.)

The very fact that Rahlves and Ligety are teammates represents another Jesse Hunt revolution. One reason the U.S. men’s team lagged in the late nineties was premature attrition. The team’s best skiers—Tommy Moe, AJ Kitt, and Kyle Rasmussen—all retired before they turned 30.

“When I took over as the men’s coach, I went back over the previous ten years,” Phil McNichol says, “and I looked at the average age of the athletes in the World Cup top ten. It was 27, maybe 28. Then I looked at the average age of retirement on our team. Which was 25.”

AJ Kitt, now a real estate broker in Hood River, Oregon, recalls a lot of good times on the World Cup circuit. “But I did it for 11 years, and after a while a burnout factor sets in,” he says. “It just wasn’t that fun anymore.”

Career longevity is a common denominator among ski racing’s elite. It’s only when you stand next to World Cup veterans like Norway’s Lasse Kjus and Austria’s Hermann Maier that you realize exactly why it pays to keep athletes racing into their thirties. Older racers have an astonishing thickness of body that younger skiers haven’t developed.

“We call it old-man strength,” says assistant coach Needell. “You race for 20 years, it’s like doing 7,000 days of extreme core work.” Top racers develop oak trunks, burly thighs, and asses as wide as Karl Malone’s. As one course technician told me, “Da big butts win.”

Keeping athletes racing for three decades means keeping them healthy, both physically and mentally. The physical component was mostly in place by the 2002 Olympics. The money raised by Bill Marolt allowed the USSA to create a state-of-the-art sports-science department that revamped the team’s training regimen. Out went an emphasis on brute strength—”Our sports science consisted of doing push-ups until we passed out,” Kitt says—and in came a focus on cross-training, balance, and body chemistry. During the season, it’s all about optimizing the time on the mountain.

“About five years ago,” says USSA sports-science director Andy Walshe, “we figured out that the best way to train was to have high intensity on snow and then make sure the athletes recover well, so they’re primed for the next day’s training.”

In practice, that means Miller, Rahlves, Schlopy, and their teammates aren’t doing endless laps on the training hill. They’ll do five or six runs at race-day intensity and then head back to the hotel fitness room and briefly pedal on stationary bikes to flush the lactates and stay limber. Nothing is left to chance. Trainers take blood samples and test lactate levels while the athletes spin and sip a specially formulated recovery drink.

To keep morale up and the spirit fun, Morin schedules pick-up soccer games with the women’s team. John McBride commemorates each athlete’s birthday with a pie in the face. Phil McNichol distributes bowling shirts embroidered with hot-rod flames to any racer who scores World Cup points by placing in the top 30. “C’mon, boys,” McNichol will tell his squad the night before a race. “We’re gonna get our flames on tomorrow.”

ON THE LAST DAY OF TRAINING before World Cup officials shut the Sölden GS course down to groom it for the season opener, the gossip in the gondola line was about the American world champion, who still hadn’t shown up. “Is Bode here?” an Austrian coach asked an American traveling with the team. “How’s his brother?”

A week earlier, Miller’s younger brother, Chelone, had nearly been killed while riding his motorcycle without a helmet. He’d crashed on a gravel road near the family home in New Hampshire and sustained serious head injuries. Miller delayed his trip to Austria to stay with him. The 2005 champ was expected to arrive by the end of the week—his brother was stable but still in serious condition—but nobody knew for sure. Bode lives on Bode time.

As Rahlves, Knight, Ligety, and their teammates gathered at the top of the training course, a guy with a blue Barilla helmet and a big smile barreled into the lineup.

“Look who’s here!” Knight said.

“What’s going on, boys?” said Bode Miller.

“When’d you get in?”

“This morning.”

“Fuckin’ A.” He hadn’t even stopped for breakfast.

“I’m hard,” Miller said. “You know I’m hard.”

Just then a mob of Austrian kids caught up to Miller. “Bode Mee-lah! Bode Mee-lah!” they shouted. Miller graciously signed their helmets and gloves. It’s always a shock to be reminded of how famous both Rahlves and Miller are in Europe. Rahlves is NBA All-Star famous; kids approach him shyly. Miller is rock-star famous; kids shout his name and tumble over one another, astonished to find themselves so close to their hero. Miller isn’t just good; he’s historically great. Only two men have ever won in all four disciplines in a single season: five-time overall champion Marc Girardelli of Luxembourg, who ruled the World Cup in the eighties and early nineties, and Miller.

The ski god signed the last helmet and plunged down the course, still wearing a fleece vest and baggy shorts over his spandex; everyone else was in a one-piece skin suit. “He’s in his clothes,” one of his teammates said. “That means he’ll only beat us by a full second.”

Some aspects of Miller’s greatness are evident to the naked eye. On the Sölden GS course, for example, I watched every racer come down holding a tuck until the fifth gate, after which they sprang upright, gaining control but losing speed. Miller not only held his tuck through the fifth gate; he kept it through the sixth.

One morning, I listened to Miller and Rahlves discuss how to overcome a challenging section on the course. “Down bottom, that delay, you gotta keep rippin’ it, man,” Rahlves said. Miller responded with a string of technical terms that were impossible for me to comprehend.

“Trying to understand Bode’s skiing is like trying to understand superstring theory,” says Chip Knight. “We all watch and go, ‘How the hell does he do that?’ ” Greg Needell has watched hundreds of hours of Miller on video. His conclusion: “No other skier, ever, has had Bode’s instinct for sensing where the fall line is. And no other skier has Bode’s physical ability to put himself there.”

If Miller was the prodigy, marked early for greatness, Rahlves was the quintessential American champion. He struggled for years before making the team, scraping his way to the top through determination and hard work. He understood how everything mattered and how the little things added up. One day I watched Rahlves finish a run at Sölden. Instead of standing while he spoke with his ski tech, as most racers did, Rahlves sat on a stool and splayed his legs to rest his muscles. Speed is in the tiniest details.

While Rahlves is the team’s cool, mature leader, Miller induces more ulcers than any racer since battlin’ Bill Johnson. Last year Miller blasted the unfairness of the World Cup system—top guys like him make $3 million a year while racers like Ligety struggle to get by—and threatened to start his own tour. Before the 2005–06 season, he caused a commotion by declaring that performance-enhancing drugs like EPO ought to be legal to help athletes avoid career-ending injuries. And coaching? Don’t bother him with it.

“Skiing at this level is a lot less about coaching than anybody thinks,” Miller says. “There’s not a lot a coach can do other than help with race-day routines.”

That isn’t to suggest that Miller won’t offer his own coaching to teammates, solicited or not. “A lot of the guys are my good friends, and I want to see them do well,” Miller told me after practice one day. “But they really just do not respond well to a peer giving them any kind of advice or criticism. The fact is, I’ve taken a much more proactive role in my situation, and that’s led to getting better results. It’s basic stuff like nutrition, rest, having your own space. [Miller travels on the World Cup in his own motor home.] I tell them if they want to really take their best shot, they’ve got to do the same. But the guys just don’t fucking address it. They’re just like, ‘Oh, I listen to my coach. If it was important, the coaches would bring it up.’ “

It’s a little like Ted Williams wondering why the rest of the Red Sox can’t just hit the damn ball like he does. Veterans like Rahlves, Schlopy, Knight, and Spencer have known Miller long enough to shrug it off.

What’s taken more getting used to is Bode’s life in the spotlight.

“As Bode has become more successful, he gets pulled in more and more directions, and that can detract from the team,” says Dane Spencer. Miller’s outspokenness doesn’t particularly bother him or other guys on the team, Spencer adds. “What’s frustrating is we don’t get to see him as much, and don’t get the opportunity to train with him as often.”

That’s a frustration for the coaches, too. It’s a common belief in the ski-racing world that speed breeds speed: Training with the top dogs forces everyone around them to run that much faster. “When Bode and Daron are both around, you can feel it,” says Greg Needell. “Guys lift their games. Everybody wants to beat the best in the world.”

OLYMPIC YEARS ARE INTENSE on the ski team. Young kids run all out to make the squad. Veterans race for one more shot at glory. Pressure mounts. Bill Marolt has set a public goal of winning more medals in ski and snowboard events than any other nation. Jesse Hunt says he expects the men’s and women’s alpine teams to bring home a total of eight—four times as many as they nabbed in Salt Lake City.

The U.S. can race four athletes in each of the five Olympic events. In theory, every slot is up for grabs; the top four ranked skiers in each discipline will go to Turin. In reality, Bode Miller will race in all five—and could medal in each. Daron Rahlves will race in three, and is expected to medal in at least the downhill. Unless Miller or Rahlves falters, the rest of the team will fight for two open spots in each discipline (three in slalom and combined, where Rahlves doesn’t compete).

“Everyone knows what’s at stake,” says Mike Morin. “We’ve got one of the most competitive teams we’ve ever fielded in an Olympic year.”

On the last training day in Sölden, the team lined up for a time trial. Seven slots were available for U.S. skiers in the upcoming GS race at the World Cup opener. Five were spoken for. Chip Knight, Ted Ligety, and tech skier Tom Rothrock, 27, would fight for the last two.

It was a rare intramural battle. Most national ski teams are “team” in name only—it’s every man for himself. The American men are anomalies: They cheer for one another. When Miller completes a run in a race, he’ll radio Rahlves or Schlopy with beta on course conditions.

Ligety bolted out of the gate and laid down a killer run. Rothrock followed. He was a bit slower but still close. Knight stepped up to the starting gate and huffed twice. “Come on, Chipper!” shouted Miller. Knight banged through the start. “He fuckin’ smoked those wands!” said Miller.

He smoked the wands but not the course. A little more than one minute later, Morin announced Knight’s time over the radio. It wasn’t enough. Ligety and Rothrock would be racing at Sölden, where Ligety would stun the field by nabbing eighth.

An hour later, the ski team quit the course and tossed their gear on the softening snow near the parking lot. The sun bounced off the sugar-dusted Alps, and the resort’s beer garden provided a soundtrack of laughter and clinking glass. Miller spoke with an Austrian TV crew while signing a kid’s helmet. Schlopy chatted in German with a friend from Liechtenstein.

At a picnic table, Ligety flirted with a couple of racers on the U.S. women’s team, telling one of them something about the heisse scheiss. Less than two weeks later, during Ligety’s second run of the Sölden GS, he would lay down the fastest time of any racer in the heat. Though the combined times would place Hermann Maier first and Miller second, in one dazzling run Ligety would beat them all.

But right then the pressure of the World Cup, the Olympics, and Bill Marolt’s goals appeared to be far in the future. Right then, it was just good to be an American in Europe, basking in the warm glow of last year’s accomplishments, feeling the sun on your face, and knowing that, for at least that moment, the heisse scheiss in the skiing world was you.

Downhill: The granddaddy of speed races, and one of the riskiest events in any sport. Downhills are run over an icy, two mile-long course, with pitches up to 60 degrees and jumps that can keep racers airborne for more than 100 feet. Racers make one run, winner take all. Top speed: about 90 miles per hour.

Super-G: This event, which made its Olympic debut at Calgary in 1988, combines the speed of downhill with the big, smooth arcs of giant slalom. It’s held on a mile-and-a-half-long course, with gates set about 155 feet apart. One run only. Top speed: 70 miles per hour.

Giant Slalom: A technical event, GS features wide turns determined by breakaway gates placed 60 to 100 feet apart. The top 30 racers in the first run make the cut for the second. Final results are determined by the combined times from two runs. Top speed: about 40 miles per hour.

Slalom: A technical event in which skiers, protected by plastic body armor, bash through 55 or more breakaway gates set an average of 32 to 50 feet apart on a course one-third of a mile long. As in the GS, the top 30 in the first run move to second run, and the best combined time wins. Top speed: about 35 miles per hour.

Combined: This event—one downhill run followed by two slalom runs, all on the same day—is a great test of versatility and endurance. Final results are determined by adding the total time of all three runs.