Last April, Italian skier for the fastest ski run, in an avalanche-prone couloir in Vars, France, called Chabri├Ęres. He was one of 21 competitors at the annual Speed Masters, where contestants descend at the highest velocity possible. Perfect conditions at Chabri├Ęres are rare, despite the site being maintained by a winch cat, and the top of the track was in such poor shape that Origone opted not to start from the pinnacle for fear heÔÇÖd be thrown off course, which can prove fatal at high speeds. Instead, the 36-year-old mountain guide from northern ItalyÔÇÖs Aosta Valley was lowered into the chute by a rope, then stabilized by a race official, who was also roped up.

Chabri├ĘresÔÇÖs pitch is so precipitousÔÇöin some spots, itÔÇÖs as steep as 47 degreesÔÇöthat when pushed off, he began accelerating almost as fast as a Formula One race car. Seventeen seconds later, crouched in an aerodynamically perfect tuck, he was clocked at 156.978 miles per hourÔÇöthe fastest anyone has traveled on land without the assistance of a motor. At the end of the kilometer-long track, he made S-turns to slow himself down. (Virtually all other competitors wedge┬átheir way to a halt.) It was just enough to break his previous record, 156.868 mph, set in 2014.

Because a higher start can translate to more speed, Origone believes his compromised toe-off last year in Chabri├Ęres means he could have gone even faster. In March, Origone will return to Vars and attempt to hit 158.45 mph.

Origone┬áis practically anonymous outside the sport.╠řEven in Italy, many know him only for rescuing a Pakistani climber while attempting K2 without supplemental oxygen in 2014.

Forty years ago, OrigoneÔÇÖs records would have made him famous. In 1975, countryman Pino Meynet earned a small fortune and was feted on national television after setting a record of 120.785 mph. But the days when speed skiers were celebrated like heroes are gone. Origone, who has held the world record for ten years and has broken his own mark twice, is practically anonymous outside the sport. Even in Italy, many know him only for rescuing a Pakistani climber while attempting K2 without supplemental oxygen in 2014; after conceding his own summit bid just below the infamous Bottleneck, he found the disoriented man at camp four and led him down the mountain from 25,000 feet.

As accomplished as he is in the mountains, no one can touch him when it comes to speedÔÇöhe has won eight FIS World Cup titles and five world championships. (Origone has no Olympic medals because itÔÇÖs not an Olympic sport.) ÔÇťHe knows that if he makes no mistakes, he canÔÇÖt lose,ÔÇŁ says Bastien Montes, a 30-year-old French racer who survived the fastest crash in history, a 151-mph slide that left him with fourth-degree burns from shoulder to buttocks.

Speed skiing has been around in some form since at least 1867, when a California woman named Lottie Joy set an unofficial benchmark of 48.9 mph. Races became more widespread in the mid-20th century, and from the 1960s to the 1980s, the world record seemed to change hands almost monthly. American skiers Dick Dorworth, Steve McKinney, and Leif Nelson were crowned in places like Silverton, Colorado; Portillo, Chile; and Les Arcs, France. ÔÇĘThe International Olympic Committee staged a speed-skiing demonstration at the 1992 Winter Games in Albertville, France, but tragedy upset the momentum when Swiss racer Nicolas Bochatay collided with a snowcat during a warmup run and was killed.

Origone, who comes from a family of hoteliers and ski instructors (his younger brother Ivan is his roommate and biggest rival, with a top speed of 155.77), epitomizes the sportÔÇÖs current conflict. Speeds keep getting faster; rewards keep getting smaller. When Origone set his first record, in 2006, he received roughly $11,500. Now not even the four races offer prize money. ÔÇťThatÔÇÖs shit,ÔÇŁ Origone snorts.

Still, it hasnÔÇÖt affected his year-round devotion to the sportÔÇöor that of the approximately 80 other men and women competing at its highest levels. Indeed, Origone is one of the lucky few among them: the Italian Ski Federation covers his expenses, and Atomic gives him skis. (Most racers compete with little financial backing.) ÔÇťYou spend every penny youÔÇÖve got to do this,ÔÇŁ says six-time U.S. champ Don Strickland, 53, who works as a carpenter in Glenwood Springs, Colorado, and has often been the lone American in the elite World Cup standings in recent years. ÔÇťYou train all year long for ten minutes of combined run time each season.ÔÇŁ

Origone practices in a wind tunnel and follows a rigorous physical regimen that includes holding his tuck on a slackline with 30 pounds of extra weight. One of the brawniest men on tour at six-foot-one and 195 pounds, he has reigned largely because he keeps his skis flat and maintains his tuckÔÇöand thus his speed. Origone has been criticized for lubricating his suit to improve wind resistance but denies it gave him any advantage.

If he gets a smoother track this month at the Speed Masters than he did last year, when tiny bumps bucked many racers off their lines, he thinks he can again make history. ÔÇťMy only target,ÔÇŁ he says, ÔÇťis to go faster and faster.ÔÇŁ┬á

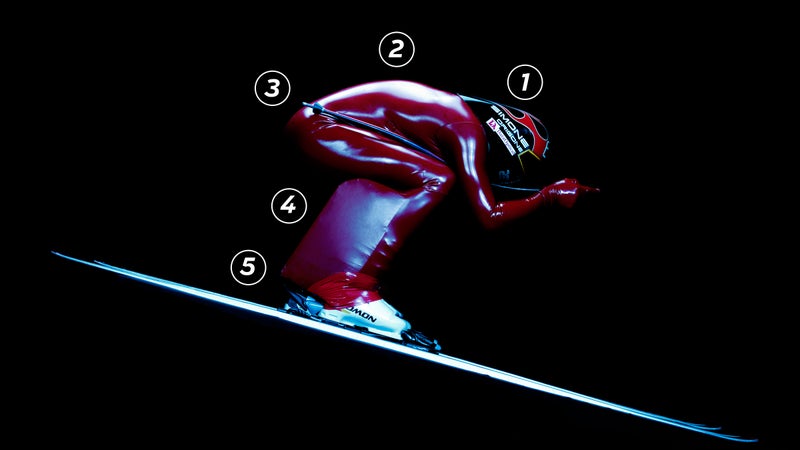

Origone's Wind-Cheating Gear

1. Helmet

OrigoneÔÇÖs is designed to cover his shoulders, reducing drag.

2. Suit

The design of his nearly frictionless suit, which is made from air-tight latex, has remained unchanged for 15 years.

3. Poles

The short poles are custom-built to fit OrigoneÔÇÖs tucked body and help him stay balanced and in good position.

4. Fairings

Aerodynamic foils behind his shins increase his top speed by an estimated four to five miles per hour.

5. Skis

Longer than Olympic downhill skis and extremely flat for stability, his 238-centimeter Atomics have dull edges to prevent catching on snow.

A Brief History of Speed-Skiing Fatalities

Even minor mistakes can be deadly

1965: The sportÔÇÖs first death was Walter Mussner, who fell just before the finish line in Cervinia, Italy, and later died.

1974: Swiss skier Jean-Marc Beguelin kept his head tucked too long and was killed after veering off course in Cervinia.

1992: During an Olympic exhibition in France, Nicolas Bochatay of Switzerland died after hitting a snow-grooming vehicle.

2005: Italian Marco Salvaggio hit a small rock while approaching the starting line and suffered fatal head trauma.

2007: In Les Arcs, British racer Caitlin Tovar lost control near the start, slid off the track, and fell 3,000 feet to his death.

Other Non-Motorized Records

27.79 mph: Running; Usain Bolt, 2009

61.3 mph: Windsurfing; Antoine Albeau, 2008

80.74 mph: Skateboarding; Mischo Erban, 2012

95.69 mph: Ice luging; Manuel Pfister, 2010

126.1 mph: Land sailing; Richard Jenkins, 2009

156.978 mph: Skiing; Simone Origone, 2015