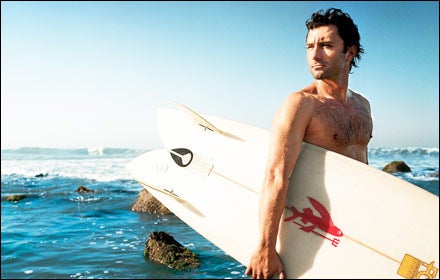

FLETCHER CHOUINARD is avoiding me. The day before I fly to Ventura, California, to meet the only son of Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard, his handler tells me he’s thinking about sneaking in a last–minute surf trip to Hawaii. But I go anyway, and when I find him he’s holding court in a sawdusty Quonset hut on the Patagonia campus, home to Fletcher Chouinard Designs.

Fletcher is a 33–year–old surfboard shaper who, with a staff of seven, produces about 1,000 environmentally friendly boards per year, which sell for between $650 and $1,300 apiece. Though it might be tempting to dismiss him as the beneficiary of offshoot–brand nepotism, he has an important role. Patagonia is in the process of converting half its business to surfing, and Fletcher is the name and face behind the only product in the line that’s actually required for riding waves. But if he has plans to someday become a bigger player at the $300 million family–owned company, he’s playing it cool. “I’m just a marketing tool, watching over the image of Patagonia,” he says. “I do what I’m passionate about, and if that promotes the tribe, then bitchin’.”

Fletcher is a brown–haired rendition of tinselly Yvon, with the same broad face, compact build, and curmudgeonly reticence. He started making surfboards in 1994, apprenticing under famed shaper Dave Parmenter before quitting college at Cal Poly–San Luis Obispo to design full–time. In 1997, Yvon folded Fletcher’s fledgling biz—which he ran out of a nearby metal shack—into the parent Patagonia brand. Once Yvon was invested, he realized that conventional boards, including his son’s, weren’t up to his durability standards.

“My dad complained that the boards I made him would fall apart too quickly,” explains Fletcher, who at his father’s urging began testing materials to replace the industry–standard fiberglass–coated foam. “When we first started, we weren’t thinking about green per se,” he says, “but it ended up that the greener, more durable materials perform better.”

Just like that, Fletcher went from shaper to innovator. His new formula combines VOC–free foam (VOC describes any number of highly toxic “volatile organic compounds”) and low–VOC epoxy resin. Though Patagonia’s designs aren’t truly no–impact—”For that, you’d have to find a log and whittle it by hand,” says Fletcher—the company is widely regarded as a pioneer in the effort to create a greener surfboard.

“They’re on the forefront of sustainable innovation,” says San Francisco shaper Danny Hess, who along with Fletcher is one of a few dozen board makers experimenting with materials like salvaged wood and bamboo.

It’s a micro–niche within the relatively small surfboard market, but for Patagonia it represents a foothold in something much bigger. With sales growth in the company’s mountaineering line holding steady between 5 and 10 percent, Patagonia is trying to elbow into the multi–billion–dollar surf–lifestyle industry, which is dominated by cash–flush giants like Quiksilver and Billabong. In 2004, to bolster its image as a legitimate surf brand, the company hired surfers Keith, Chris, and Dan Malloy and Hawaii big–wave legend Gerry Lopez and, in 2005, opened its flagship surf store in Cardiff–by–the–Sea, the epicenter of Southern California beach culture.

By last year, Patagonia’s surf sales had doubled, thanks in part to the introduction of a new, in–house–designed,crushed–lime– stone–and–wool wetsuit—greener and warmer than regular neoprene and hailed by Yvon as “the best product that’s ever come out of this company.” Patagonia CEO Casey Sheehan says they’ll open a second California surf store by the end of this year, a possible Hawaii store in 2009, and East Coast shops after that. Surfing now accounts for 10 percent of the company’s $295 million annual sales, but if Yvon has his way, that number will jump to 50 percent in the next few years. Fletcher Chouinard Designs is a notable, if not lucrative, part of this equation. “Making surfboards is not a profitable business,” says Yvon. “It’s a labor of love, but we can afford to do it because it’s a marketing investment. Fletcher’s boards give us authenticity in the surf industry. We’re not just making T–shirts and caps.”

And if his dad weren’t bankrolling it all, Fletcher’s design cred would still carry him. “If he couldn’t shape, it wouldn’t fly,” says Sam George, former editor of Surfer magazine. “Fletcher is talented, and that’s justification for what they’re doing.”

But Fletcher’s long–term role at Patagonia remains murky. When he’s not shaping boards, he’s out testing them at Ventura’s local breaks or as far away as Indonesia. As a Patagonia employee, Fletcher is on the payroll, but he comes and goes as he pleases. “He reports to himself,” says Sheehan, who’s quick to point out that the favoritism ends there. “He’s as hardworking as his dad, but he probably makes a smaller salary than the rest of the Patagonia rank–and–file.”

Along with his parents and his younger sister, Claire, 28, who joined Patagonia as a women’s lifestyle designer in 2006, Fletcher sits on the company’s board of directors—a leadership position he’s growing into slowly. “I’m not as involved with the company business as I eventually hope to be,” he admits. “I want to be able to speak confidently at a board meeting about the financials. Right now I’m like I don’t know, that sounds a little wacky.’ And then I’ll figure out what it means later.”

“He’s not necessarily entrepreneurial,” says Yvon. “He has that sense that an artist has, but artists aren’t the most practical people.”

By the looks of it, no one’s taking Fletcher too seriously. Not Yvon, and maybe not even Fletcher himself, who’s still scheming about jetting off to catch that swell in Oahu. As to whether he’ll run the place someday, the patriarch is tight–lipped, as usual. “I don’t think he’d want to take over, but his sister might,” says Yvon. “Maybe he’ll surprise me. I don’t know. I’ll probably be dead!”