April 14, 2004

conservation, animal rights

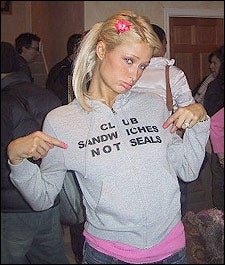

Paris Hilton models one of Danny Seo’s seal-protest fashions

Paris Hilton models one of Danny Seo’s seal-protest fashions

Canadian wildlife officials are currently tallying the number of seals harvested in this year’s Atlantic seal hunt—one of the largest seal culls to occur in decades. The hunt is part of a federally managed population reduction program that allows for the culling of 975,000 harp seals between 2003 and 2005.

Although animal-rights activists have protested the hunt, Canada’s government argues that the practice is both environmentally sustainable and economically justified.

Experts are attempting to determine whether this year’s quota of 350,000 seals was reached during the recent harvest, or if the 12,000 licensed seal hunters in Atlantic Canada—mostly off the coast of Newfoundland—can continue to hunt. Harp seals are the main target of the harvest, though the management plan also allows for culling of hooded and grey seals.

BBC News reported that during the most intensive part of the hunting season, which started on Monday, April 12 and ended Tuesday, April 13, up to 10,000 seals could be killed per daylight hour. It was estimated that nearly 140,000 seals would be killed by the end of Tuesday.

According to Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans, the harp seal population has exploded over the past three decades—nearly tripling in population to 5.2 million. The decision to increase the seal quota was meant to both control population and aid coastal communities economically depressed by the demise of the Atlantic cod fishery. But this year’s seal harvest has brought Canada under scrutiny by animal activists and the international media—in much the same way that, three decades ago, celebrities rallied behind the nascent animal rights movement and called for an end to seal hunting.

The Canadian seal hunting industry got a particularly bad rap in the 1970s when animal-rights groups circulated gruesome photos of hunters clubbing baby seals. The photos caused international protests and the U.S. banned the import of seal furs in 1972. Europe followed suit with a partial ban in 1983.

Canada eventually reduced the seal quota but never banned the practice entirely. “The industry needed to be cleaned up and it was, though perceptions persist,” Roger Simon, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans area director for the Iles de la Madeleine, told The New York Times.

According to The Canadian Press, the estimated value for top-quality pelts this year is $60 apiece and the entire industry is valued at nearly $15 million annually in Canada.

The fashion industry has largely driven demand for seal pelts as furs have made a big comeback on international runways.

Danny Seo, stylist to many of Hollywood’s most earth-conscious celebrities (see ���ϳԹ���‘s March 2004 article, ), spent the last few months working with The Humane Society to decry Canada’s seal trade.

“Furs as fashion accessories are completely irrelevant in our times,” Seo says. “The reality is that furs are being sold to luxury goods houses.”

During the seventies and eighties, celebrities like Brigitte Bardot used their fame to help shut down markets for seal fur in the U.S. and Europe. Seo is hoping the same will happen today. Many of his famous clients sport his signature shirts with slogans such as “Club Sandwiches Not Seals.” Seo’s next step is to target fashion houses, such as Dolce & Gabbana and Prada, that use seal pelts in their designs.

Despite international criticism, or perhaps nodding to it, Canadian officials have promised they will regularly review the seal hunt to make sure quotas are at sustainable levels. “If you are going to have an annual harvest you have to maintain a sustainable number,” Geoff Regan, the minister of Fisheries and Oceans, told The New York Times earlier this month. “We are going to come up with these numbers on the basis of what the herd can sustain.”