Come to the light: Nightcrawling the Gifford Pinchot Forest for signs of you-know-who.

Come to the light: Nightcrawling the Gifford Pinchot Forest for signs of you-know-who. Is there anybody out there?: Scanning the horizon for the big-footed one.

Is there anybody out there?: Scanning the horizon for the big-footed one. The Bigfoot Hot Zone

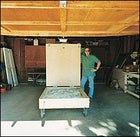

The Bigfoot Hot Zone Thrown of the ape-man!: Rick Noll displays the controversial and anatomically diverse Skookum Cast.

Thrown of the ape-man!: Rick Noll displays the controversial and anatomically diverse Skookum Cast. They walk among us: BFRO “curators” Jeff Lemley, above, and Leroy Fish in the field, below.

They walk among us: BFRO “curators” Jeff Lemley, above, and Leroy Fish in the field, below.

Heir apparent Jeffrey Meldrum in his lab at Idaho State.

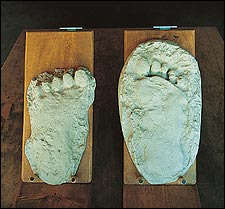

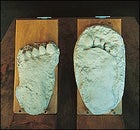

Heir apparent Jeffrey Meldrum in his lab at Idaho State. Scientific proof?: Plaster casts frm the BFRO collection.

Scientific proof?: Plaster casts frm the BFRO collection.

I’M STANDING WITH A GROUP OF HUNTERS from the Bigfoot Field Researchers Organization at a forest-road turnout overlooking Quartz Creek Valley, a remote hollow deep in the primal animal heart of Washington’s 1.3 million-acre Gifford Pinchot National Forest. It’s midnight, and LeRoy Fish, a 59-year-old wildlife biologist, former Alaska hunting guide, and BFRO stalwart, is setting two stereo speakers on the roof of his crew’s SUV and plugging a Sony Discman into a 500-watt amp powered by a spare car battery. In the world of Bigfoot enthusiasts, there are many purported sound recordings of the quarry, all of which are named after the place of origin: Sierra, Puyallup, Snohomish. This is the Tahoe call, Fish explains, captured near the lake in August 2000.

“Everybody ready to listen?” Brian Smith, a cocky 33-year-old apartment manager from Walla Walla, says into his CB radio. Five BFRO spotters parked at listening posts below us and across the valley give Smith a 10-4. “Our ears are on,” comes the reply.

Fish presses play, and the speakers erupt with the eeriest chalkboard-scratchin’, terror-in-the-dark screech I’ve ever heard.

REEEEEeeeeeeeeeeeeoooooowwwwghghghghghgh!!!!!!

Silence.

“If there’s an animal out there,” Fish whispers, “it’ll return call almost immediately.”

We stare out at the blackened valley, ears cocked.

More silence.

“Let’s try it again, a little louder,” says Smith.

Fish broadcasts the screech over and over for the next three hours, but the Tahoe call draws no lovelorn Sasquatches out of the woods. Around 3:30 a.m., Fish and Smith radio the spotters that it’s time to call it a night. Then they unplug the speakers and head back to camp for a couple hours of sleep.

They’ve got to be rested. Tomorrow could be the day.

THERE ARE THREE POSSIBLE REACTIONS to the idea of Bigfoot. Sit anybody down to watch the Patterson film—the grainy 16mm clip of a man-beast loping across a meadow in northern California in 1967, which is to serious ‘squatchers what the Zapruder film is to JFK-assassination buffs—and they will inevitably respond:

A: Bigfoot lives!

B: That’s a guy in a gorilla suit.

C: I’m intrigued yet unconvinced.

Most BFRO members can be classified as a Type A. Most reasonable folks are Type Bs. I’m a Type C.

On the Night of the Screech, the BFRO convoy consisted of two four-wheel-drive SUVs and eight guys outfitted with night-vision scopes, million-candlepower spotlights, digital cameras, GPS units, and infrared videocams. But all these pieces of hardware were mere accoutrements to the garment worn by every man in the field: belief. Belief that an eight-foot-tall ape weighing 800 pounds is alive and well and galumphing through the forests of North America. That’s the heart of the heart of the Bigfoot obsession—because as long as we never find him, he’ll always be out there, and we can keep believing. It’s a strangely comforting thought for your average ‘squatch hunter, and kind of addictive. After hanging around in the deep woods of the Pacific Northwest, waiting expectantly for a cry, a sighting, anything—I want to believe, too.

Founded in 1995 by Matt Moneymaker, a 36-year-old Orange County, California, information technology consultant and lifelong Sasquatch enthusiast, the Bigfoot Field Researchers Organization claims 30 top “curators” (experienced Bigfooters who interview witnesses, examine fresh evidence, and debate the finer points of Sasquatch theory) and more than 300 “investigators” (junior associates who help with the fieldwork). The BFRO has no home base other than its Web site (), but its members—a majority of whom hail from British Columbia, the Pacific Northwest, and California—have access to the most sophisticated, password-protected Bigfoot database on the Internet.

“I look for people with education and perseverance,” says Moneymaker, whose own interest in Bigfoot was kindled by watching many episodes of In Search Of… in the 1970s. “Our members tend to be people with backgrounds in science, anthropology, law, law enforcement, journalism, people who’ve worked with government agencies. What we want is an ability to look at evidence and be able to pick out various possible explanations.”

The natural question to ask these guys, then, is this: Thirty-five years after the Patterson film, are we any closer to bagging Bigfoot?

To which the leading minds of the BFRO answer: Behold the Skookum Cast!

For Bigfoot hunters, the exciting thing about the Skookum Cast is that it’s not just a footprint, but parts of a whole body. A heel. A forearm. Half a buttock.

That’s right—Bigfoot’s ass!

During a September 2000 hunt in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest, down around Mount St. Helens, members of the BFRO baited a marshy plain known as Skookum Meadow with apples and melon—the idea being that the omnivorous giant hairy ape of legend might come out for a succulent bite of rotting fruit. They returned the next morning to find a crazy quilt of prints and a few apples gone. LeRoy Fish recognized coyote paws and elk hooves but couldn’t identify a set of suspiciously anthropoid forearm, heel, and butt imprints. After spending eight hours scratching their heads and pouring plaster—a regulation component of every ‘squatch hunter’s field kit—the BFRO boys came away with perhaps the most important Bigfoot find in 30 years.

Word of the Skookum Cast got out, and for the first time since the Patterson film, important mainstream scientists pricked up their ears. Over the past year, a group of them—including Esteban Sarmiento, a functional anatomist at the American Museum of Natural History; Daris Swindler, professor emeritus of anthropology at the University of Washington; and George Schaller, world-renowned biologist, conservationist, and author—ventured to the Pacific Northwest to give the cast thorough scrutiny. The results of their critique will be revealed in a documentary titled Sasquatch: Legend Meets Science, which is slated to air in November on the Discovery Channel. “I’m a doubting Thomas when it comes to Sasquatch,” says Swindler. “But I’ve looked at the cast twice now, and the imprints are certainly not of an elk or bear or anything we know of.”

For the BFRO and other seekers of Sasquatch, this is a hell of a break—and not a moment too soon. The Skookum Cast has entered the fray just as Bigfoot culture is experiencing a generational tide change. After a 50-year chase, the men who count as the Four Horsemen of Sasquatchery have either retired to their Barcaloungers or passed on. Seventy-year-old Rene Dahinden, a Swiss-born Canadian tracker, ended his days living out of a dumpy trailer on the edge of a rifle range near Vancouver, where he made a living repackaging spent buckshot. (“I wish I had me one of them $100,000 houses,” Dahinden reportedly once said. “Because then I could sell it and do more Sasquatchin’.”) He died last year. Peter Byrne, the 77-year-old Irish dandy who cut his teeth on Himalayan yeti expeditions in the 1950s, took a hiatus from Sasquatch hunting in 1997 after his last big pursuit, the Oregon-based Bigfoot Research Project, produced no significant breakthroughs. John Green, the 75-year-old Bigfoot archivist and author of the seminal volumes Year of the Sasquatch, On the Track of the Sasquatch, and Sasquatch: The Apes Among Us, has ceased to catalog new reports. And Grover Krantz, the curmudgeonly Washington State University anthropologist and author of Big Footprints: A Scientific Inquiry into the Reality of Sasquatch—and the guy who gave the chase its first scientific imprimatur—passed away this winter at the age of 70, his quest to prove the existence of Bigfoot unfulfilled.

Now, into the vacuum left by the Four Horsemen rushes a new generation of hunters bent on solving the mystery.

THE KEEPER OF THE SKOOKUM CAST is a 49-year-old BFRO curator and former aerospace engineer named Rick Noll. The latest and greatest evidence of Bigfoot’s existence sits under a blue plastic tarp in a relative’s two-car garage in a suburb of Seattle. To avoid alerting potential vandals, Noll has asked me not to reveal the object’s exact location, but I can report that the garage’s owner keeps it neat as a pin. Even the 100-pound bags of Hydrocal B-11, the Bigfoot caster’s plaster of choice, are stacked just so in a corner.

Though he maintains a dramatic leonine hairdo, Noll is a reticent and solemn man. It’s hard to tell if this is his natural disposition or if it’s been shaped by years of what Bigfooters call “the chuckle factor”—the ridicule that is every hunter’s burden. The BFRO averages 200 tips a month, ranging from claims of face-to-face encounters to campers spooked by eerie midnight howls. Most are dismissed as misidentified mammals or obvious hoaxes, but there are usually 15 to 25 that they actively check out. “We had one lady recently who sent us a snapshot she said she’d taken when she was out dancing in the woods,” Noll told me the first time we met. “Something about the animal looked awfully familiar. Then I realized where I’d seen it before.” Noll pulled out an enormous three-ring binder replete with all things Sasquatch, from faked photos to more credible examples of evidence, and put the picture side by side with an identical shot of the Sasquatch statue from The Wax Works museum in Newport, Oregon.

“This is often the kind of stuff we deal with,” he sighed.

When I come to view the cast, Noll opens the garage door and removes the tarp with the help of Owen Caddy, a local park ranger and former primate researcher. (Caddy, a recent BFRO convert, has been working informally with Noll to interpret the cast. His background suits the job. From 1995 to 1997 he studied chimpanzees in Uganda’s Murchison Falls National Park and became an expert at recognizing primate tracks.) “Owen’ll walk you through it,” Noll tells me. “It’s kind of hard to know what you’re looking at.”

No kidding. The cast looks like a congealed vanilla-caramel pudding the size of a twin bed.

“When I first looked at this thing, I saw the elk tracks,” says Caddy, pointing out two obvious hoof prints. “I’m a pretty skeptical guy, but I kept on mapping the impression order.” Next, he indicates what he has determined to be heel and Achilles-tendon impressions; they’re too wide, he says, to be elk, but just right for a large primate. The heel trench, arm print, and butt divot suggest that something bipedal sat down, dug in its heels, and leaned on its forearm.

As Noll removes excess dirt from the cast with a dental pick, Caddy and I sit on the driveway and simulate the creature’s position. “Now,” he tells me, “put your hand under your butt.” I grab a cheek. “Lift your thigh.” OK. “You feel that bone? Feel how it digs in?” I do, but I feel a lot like an infomercial stooge for saying so. “Now come look at the cast.”

Caddy, Noll, and I gaze in wonder at the bone-shaped bump in the butt print. I’ll be damned.

“I’m not saying this was a Sasquatch,” Caddy says. “But seeing that bone depression was kind of a turning point for me.”

REPORTS OF GIANT APES roaming the forests of North America have persisted for more than 200 years. The Nuxalk Indians of present-day Bella Coola, British Columbia, called it boq; tribesmen on Vancouver Island dubbed it matlox; and the Coast Salish used the word ��é�����, the closest etymological root of Sasquatch. In 1811, British explorer David Thompson claimed he stumbled upon a Bigfoot track near what is now Jasper, Alberta. Thompson was no wide-eyed naif, but he admitted in his journal that “the sight of the track of that large beast staggered me.”

Prospectors, fur trappers, hunters, and farmers continued to report sightings of hairy creatures throughout the Pacific Northwest for the next century. In July 1924, a group of miners reportedly waged a battle with a gang of enraged “mountain gorillas” while prospecting a claim near Mount St. Helens. One of the miners had shot a ‘squatch earlier in the day (somehow the body disappeared, of course), and apparently his relatives came looking for payback. The Portland Oregonian reported that the prospectors held their ground while “the animals bombarded the cabin where the men were stopping with showers of rocks.”

The modern Bigfoot era debuted in October 1958, when Jerry Crew walked into the Eureka, California, office of The Humboldt Times carrying a giant plaster footprint. Crew, a bulldozer operator, had been clearing a road through a forest in the remote Bluff Creek Valley, a few miles north of the Klamath River. For weeks he and his coworkers had found 16-inch-long, seven-inch-wide prints every morning in the freshly graded dirt. The Associated Press picked up the story and sent it out on the national wire, noting that Crew’s fellow construction crew members had coined a new nickname for Sasquatch: “Bigfoot.”

Up to this point Sasquatch had adhered to the accepted order of discovery: Native stories, explorers’ tales—now a report of contemporary tracks. But then things began to go awry. In terms of scientific credibility, Jerry Crew wasn’t exactly Louis Leakey. And his evidence, while compelling, wasn’t physical—it was not a bone, a skull, or a body. When you came right down to it, all he held in his arms was an absence of dirt.

It took a pair of cowboys to bring home the goods—and unwittingly destroy whatever shred of scientific probity still clung to the search. Roger Patterson and Bob Gimlin had met on the rodeo circuit. Both were fair-to-middling riders who scratched out a living around Yakima, Washington. Patterson’s Bigfoot obsession grew out of his reading of noted cryptozoologist Ivan Sanderson’s 1959 True magazine article “The Strange Story of America’s Abominable Snowman.”

“He’d talk about it around the campfire,” Gimlin recalled in a 1978 interview with Peter Byrne. “I didn’t care, but after a time you find yourself looking for the doggone thing, too.”

Though Gimlin, then 36, remained a Type C skeptic, he gamely accompanied the 34-year-old Patterson on Sasquatch forays around southwestern Washington. In October 1967, Patterson heard that fresh tracks had been found near the site of Jerry Crew’s original discovery at Bluff Creek. He and Gimlin loaded their horses into a truck and road-tripped to northern California. A week or so into their search they found what they were looking for.

You know the clip. Tall gorilla. Long arms. Creekside lope. Stay-away-from-my-shit glare. Late-sixties Kodachrome color scheme.

Eager to get scientific confirmation of the evidence, Patterson enlisted the help of John Green and screened the film for a number of experts—to no avail. The director of a primate research center in Oregon was troubled by the appearance of hair on the animal’s breasts, and a naturalist at the British Columbia Provincial Museum thought the crested skull was all wrong. But the most crushing blow came from John Napier, a well-known author on early man and director of the Smithsonian Institution’s primate biology program. Although he remained open to the possibility of Sasquatch’s existence—”Too many people claim to have seen it or at least to have seen footprints to dismiss its reality out of hand,” he wrote—Napier also found inconsistencies in the animal’s anatomy and movement. “There is little doubt,” he added, “that the scientific evidence taken collectively points to a hoax of some kind.”

In 1968, spurned by the scientific establishment, Patterson took his message to the masses. After padding his 59.5 seconds of footage with supporting “documentary evidence” (film shot at Bluff Creek before and after the encounter, plaster footprints cast at the site), Patterson embarked on a barnstorming tour of the American West, renting small theaters for one-night stands that combined the cheap thrill of a circus sideshow with the marketing instincts of ski-movie king Warren Miller. Patterson’s crusade was cut short when he died, nearly broke, of Hodgkin’s disease in 1972, but he bestowed upon his creature an eternal afterlife of controversy, feverish speculation, and kitsch, from hyperventilating episodes of In Search Of… to that classic of white-trash car accessories, the Bigfoot gas pedal.

Even the Patterson skeptics have their own dubious lore. One of the most pervasive theories is that Patterson colluded with Planet of the Apes makeup artist John Chambers. Like most conspiracy theories, this one contains delicious bits of plausibility, such as the fact that production on the original film wrapped on August 10, 1967—ten weeks before Patterson’s encounter—leaving Chambers with surplus ape suits and a window of opportunity. There are logical flaws, though: The Bigfoot in Patterson’s film (subsequently dubbed “Patty”) looks nothing like a simian Roddy McDowall, and one wonders why the makeup artist would hook up with a nickel-and-dime horse tender. Chambers periodically denied the story, but the tale lives on.

IF BIGFOOT STUDIES HAVE A MARTYR, it’s Grover Krantz, the first bona fide scientist who came to believe in Sasquatch, and who paid dearly for it. Not long before he died, I interviewed him at his home on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula, where he retired after three decades as a professor of anthropology at Washington State University in Pullman. He sat in his chair, smoking like he was competing to see how fast he could empty the pack. The doctors had told him he had terminal pancreatic cancer, so what the hell. His brand: True.

“To begin with, I was trying to find out if it was real,” Krantz told me. “Then I wanted to understand it, figure out what it was. Now I want to prove it exists before I die.”

The grizzled professor—whose solid research and writings in his field of expertise, the use of fossil bone evidence in the theory of human evolution, never received the kind of attention his Bigfoot enthusiasm attracted—joylessly recounted his story. He’d seen my kind. I’d misquote him, paint him the fool. Krantz didn’t care. He’d already been through the wringer: lost promotions, professional ridicule, the loneliness of a Berkeley-trained scientist in a field riddled with amateurs, hoaxers, and nuts. “It is tantamount to academic suicide to become associated with any of these people,” Krantz once wrote. Yet he did it anyway.

It was Cripplefoot that convinced him. In the late fall of 1969, Rene Dahinden, John Green, and other Bigfoot hunters descended on Bossburg, Washington, an old mining town on the Columbia River about 15 miles south of the Canadian border. Locals had reported a Sasquatch leaving unusual prints just outside the city limits. Krantz drove out to Bossburg a skeptic. “I gave Sasquatch only a 10 percent chance of being real,” he told me. After retracing the tracks at the site, the professor brought a cast pair back to his lab. The 17-inch left foot appeared normal, but the right foot curved like a C and displayed enormous bunions and splayed toes.

Applying what he knew about primate feet, the dynamics of weight distribution, leverage, and load arms, Krantz calculated the necessary position of an 800-pound ape’s ankle, heel, and toe base, and compared that to the measurements of the track. “They were right on,” he said. “Nobody could have faked that.”

Krantz came to believe that Sasquatch might have descended from Gigantopithecus, a huge primate that roamed southern China more than 300,000 years ago. (Gigantopithecus is no fiction; its bones are part of the fossil record. And Gigantopithecus could have migrated to North America on the Bering Strait land bridge.) He spent much of the next 20 years working out the details of a Sasquatch’s day-to-day existence. Once in, he was in big.

“Humans don’t constitute any threat to Sasquatch,” Krantz said. “Once in a while I’ll run across somebody who believes early Homo sapiens might have killed off Sasquatches in some areas.” The professor scoffed. “Sure. With a bow and arrow they’re gonna bring down a Sasquatch. When we can’t do it with a goddamn gun!” (This was, of course, a reference to the notorious “battle” between miners and Sasquatches around Mount St. Helens in 1924, among other incidents.)

Even more than his belief in the existence of Bigfoot, Krantz’s conviction that it was acceptable to shoot a Sasquatch attracted vehement criticism. Discussing the issue, Krantz seemed motivated more by manly admiration for the ape’s prowess than by specimen lust. “If you drop a Sasquatch with a gun,” he warned, “the first thing you want to do is reload.” Once you fire, your main problem won’t be dragging a quarter-ton carcass out of the forest; it’ll be reaching the truck alive. “Start throwing rocks at it,” he said. “If you don’t have rocks, get a long stick and poke it. You want to make sure it’s dead.” And even if the beast is dead, its mate may charge out of the trees and kill you.

In Bigfoot culture’s raging ethical debate—Should we shoot a Sasquatch?—Krantz unapologetically defended his loaded-for-bear position. “I wouldn’t want a live one captured,” he told me. “That would be the cruelest thing I can imagine. Shoot one. Being dead never hurt anybody.”

That attitude didn’t endear him to missing-linkists, who believe Bigfoot may be as much human as ape. It struck others, including most members of the BFRO, as an unsporting method of specimen collection. But Krantz had an arm’s-length relationship with the BFRO anyway; he contributed his expert opinions from time to time, but he was not a member. Even after inspecting the Skookum Cast three times, his opinion of it was tempered by a cranky ambivalence.

“I don’t know what it is,” he told me. “I’m baffled. Elk. Sasquatch. That’s the choice.”

Crushing another cigarette, Krantz suggested moving our conversation to his garage, which he had converted into a tiny natural history museum. Skulls of all shapes and sizes stared out from the walls: wolverine, seal, monkey, cow, cougar, badger, porcupine, nutria, beaver, camel, dolphin. Prehuman skulls (Australopithecus, Homo erectus, Neanderthal) occupied their own gallery. More than 70 Sasquatch footprint casts lined the opposite wall.

“Where’d this Bigfoot hand imprint come from?” I asked.

“Northeastern Washington,” Krantz said. “The guy who got it wouldn’t tell me anything else. He thought he had a prime place, didn’t want anyone else to investigate.”

“Is secrecy still a problem?”

He nodded. “If they’ve been in this for a while, they know what the goal is,” he said ruefully. “There’s a first prize out there. Once it’s been awarded, the scientists will take over.”

The professor sparked another True.

“There is no second prize,” he said.

GROVER KRANTZ PASSED AWAY on February 14, 2002, sent across the river without his prize. In his will, he gave his footprints, files, and books to his successor, Jeffrey Meldrum, a 44-year-old associate professor of anthropology at Idaho State University. (The bones his wife kept to sell and make some money.) In April, Meldrum backed a van up to Krantz’s garage, packed the stuff up, and drove it home to Pocatello, Idaho.

Over the last six years, with Krantz less active in Bigfoot hunting, Meldrum has become the anchor keeping this fringe science from drifting into farce. A charming guy with a cop mustache and a brown moptop, Meldrum made his scientific reputation in 1997 by discovering, with Duke University physical anthropologist Richard Kay, a previously unknown and long-extinct species of South American primate based on 12-million-year-old teeth unearthed in central Colombia. As a specialist in evolutionary morphology—the study of how animals have come to be shaped the way they are—Meldrum is one of the country’s top experts in primate foot mechanics.

In 1996, an editor at the science journal Cryptozoology asked him to review an obscure book called Bigfoot of the Blues, a nonfiction account of a Sasquatch tromping around the Blue Mountains near Walla Walla, Washington. Meldrum drove to Walla Walla and met the book’s main character, an old ‘squatch hunter named Paul Freeman, who led him to a fresh set of tracks. How convenient, thought Meldrum, relishing the chance to debunk the mystery.

But he couldn’t. “When I got on my knees and looked closely,” he recalls, “I could see dermal ridge details”—the dips and whorls of fingerprints—”that would be awfully hard to fake.”

In his lab in the Life Sciences building at Idaho State, where I go to meet him, Meldrum throws open drawers full of bones and footprints to find a cast of that Blue Mountain track. “Here it is,” he says, holding up a white Shaquille-size plaster cast. “The subtle detail is incredible. Both humans and apes have only two phalanges, or segments, in their big toes and thumbs, and three in the rest. See this small toe? There’s one, two, three phalanges. But look at the length of that. The foot is only about 15 inches, yet the small toe is as long as my pinkie finger. What that tells you is that this foot would have a grasping ability as good as my hand.”

Fully hooked, Meldrum examined print casts that dated back to the late 1950s. Some he tossed as obvious hoaxes. Others contained impossible-to-fake signs of veracity. “When they discover tracks, most people cast only the clearest footprint,” he says. “I looked for the messier prints, because they’re the ones that tell me something about how the animal moved.”

Then an even stranger thing happened. He started to recognize identical prints found years apart. “Here’s the Bigfoot that Jerry Crew cast in 1958,” he says, holding up a plaster cast familiar from the Humboldt Times photo. “Now here’s a track found near Hyampom, California, about 60 miles south, in 1961. When you look at the shape, proportions, and relative positions of the toes, they’re from the same guy. I say guy because it looks like a big male.”

For Meldrum—who is a curator in the BFRO—the discovery of the Skookum Cast was also momentous. “The ridge detail I saw in the skin eliminates bear, elk, and coyote,” he told me. “That sort of detail is characteristic only of primates.”

OK then, I ask, if an ape really is leaving these prints, why haven’t we found a body? Why isn’t there a single damn skull?

(The failure to produce a body is, of course, the most powerful ammo deployed by critics of belief in Bigfoot. Citing that failure, Michael Shermer, who debunks pseudoscience professionally as the editor of Skeptic magazine and as a columnist for Scientific American, barely registers Sasquatch on his radar anymore. “New species of smaller organisms are found all the time, and most of the people I meet who are into cryptozoology seem OK,” says Shermer. “But Bigfoot really isn’t in that category anymore. After 100 years of anecdotes, stories, sightings, and footprints, it’s time to cough up the body or forget it. To name a new species, we need to have a complete type specimen. But they’ve got nothing.”)

“Think about it,” Meldrum says, gamely taking up the challenge. “It’s rare, reproduces infrequently, and if it’s like other apes, it may live for 50 years. It’s at the top of the food chain, so death most likely comes from natural causes. When an animal is ill or feeble, it’ll hide somewhere safe, which makes it more difficult to find any remains. Scavengers strip the carcass and scatter the bones. Rodents chew up what’s left for the calcium. Soil in the Northwest is acidic, which is conducive to plant fossilization but not to bones. They disintegrate.”

Meldrum’s academic career hasn’t exactly been helped by his research, but neither has he faced the ridicule that dogged Grover Krantz. “There’s a different climate now than when Grover put his neck on the chopping block,” says Meldrum. During his tenure review a few years ago, some colleagues looked askance at his Sasquatch work. “There were people in my department who would have denied me tenure on that basis alone,” he says. “But there were others who said the subject doesn’t matter—it’s the way in which I went about doing the science.” Meldrum’s scientific method passed muster, and he was awarded tenure.

“If it turns out to be an ape,” says Meldrum, revisiting my question, “it’s not going to overturn our ideas about human evolution or even primate evolution. In fact, it’ll confirm what some of us suspect, which is that descendants of Miocene-period apes populate every northern continent.

“The most disconcerting thing,” he concludes, “will be the crow that will have to be eaten.”

IT’S MIDNIGHT AGAIN, ANOTHER NIGHT on the BFRO stakeout, and I’m crammed into Brian Smith’s Isuzu Trooper. We’re bouncing down a logging road in the Gifford Pinchot outback, shining a huge spotlight into the woods, still looking for Bigfoot.

“I’m 99 percent sure the creature’s not going to attack me,” says Roland Wolfe, 63, a retired real estate agent from Boise who spends up to four months a year roaming the West in search of Sasquatch. After reading hundreds of sighting reports, Wolfe says, he believes the beast would rather flee than fight.

Smith pipes up. “I think if you were to chase a Bigfoot, that might be when it tries to kick your ass,” he says.

Wolfe shifts in his seat and adjusts his ass-kicking insurance, a holstered .44. He has no intention of shooting a Sasquatch, he says; the gun’s just there for protection from the unknown. Still, he dreams of high-tech devices to help track one. “Have you heard about these titanium exoskeletons the army’s working on?” he asks. “It lets you climb hills without burning out your thighs. With something like that you could stay close enough to a Bigfoot to follow it.”

“If you wanted to,” Smith says, downshifting into a switchback.

“If you were crazy enough,” Wolfe says.

As I’ve come to find, crazy is a matter of degree. Two days later, after the spotlights, the screech session, and more apples fail to attract any ‘squatches, the frustrated BFRO crew gathers around LeRoy Fish’s truck for a postgame wrap-up.

“A lot of this work is pretty tedious,” Jeff Lemley, a 32-year-old BFRO curator from Hood River, Oregon, confides to me. Yet the men are convinced they could bring the beast home if only they had the resources. They need more camtrackers. They need people in the field for weeks at a time. They need money for DNA tests of hair samples. “I know we can do this,” says Fish. “I’m saying bait stations, bait stations, bait stations!”

(Like Krantz and Dahinden before him, LeRoy Fish didn’t live to see his dream come true. He died of a heart attack in March without ever laying eyes on the elusive being he seemed certain was out there watching us.)

That day, before packing up my stuff and heading back to civilization, I took a walk alone in the woods. Roland Wolfe’s curious description of Sasquatch—”the creature,” he called it—kept rattling around in my head. Why do we need the creature to exist? Maybe because this sort of wild two-legged phantom has been with us as long as we’ve been able to tell stories, an icon summoned from the shadowy ravines of the subconscious—the Green Man, the yeti, the Jersey Devil. As Richard Bernheimer wrote in his 1952 study, Wild Men in the Middle Ages, the man-beast embodies “the impulses of reckless physical self-assertion which are hidden in all of us, but are normally kept under control.”

The Bigfoot hunters desperately want their wild thing to be out there, living beyond the bounds of our control. And they understand that there’s an ocean of forest in which that wild thing can hide. Most of us forget this. Thirty years of dire warnings about the loss of wild lands have left us with the impression that tiny atolls of trees are all we have left. Please. Drive out into the rural North American West. Cruise from British Columbia to the middle of California. Turn off the highway just about anywhere and head down a forest road. Five minutes later, chances are you’ll be alone in the middle of nowhere. Even at noon you won’t be able to see more than ten yards through the trees. Tough to hide? You’d have to sit in the middle of the road all day to be found.

Since my hunt in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest with Fish, Wolfe, Smith, and friends, the BFRO has come into possession of new footage purporting to show a Sasquatch booking across a mountain meadow. Known as the Memorial Day video, it was shot in late May 1996 in the Okanogan foothills of north-central Washington. It’s unfocused and grainy, but something apelike is clearly running across that field. It’s just impossible to tell exactly what. It occurs to me that this tantalizing smear of pixels perfectly captures the thrilling, doomed venture that is the hunt for Bigfoot: Here is the thing before our very eyes! And yet it proves nothing.

As darkness filled the space between the trees that last day, I hustled back to my car, peering expectantly around each bend in the road and over my shoulder. It’s one thing to recognize that a belief in Sasquatch reenchants the forest. It’s another to feel the creepiness inspired by that faith…and start to believe.

Contributing editor Bruce Barcott wrote about risk and outdoor liability lawsuits in July.