Run For It

It sounds too good to be true: a star miler turned criminal goes to prison, links up with a legendary track coach, trains behind bars until his feet bleed, and earns a spot on the U.S. Olympic team. Is the real world ready for Jon Gill's dream?

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

On a perfect day for a jailbreak, Jon Gill snugs up his running shoes and takes a few deep breaths. It’s a warm March morning in 2002, and under a sunny Oregon sky, Gill jogs past some prison guards and ratchets up his speed, moving faster until he reaches both optimum velocity and a familiar dream state. His body continues to trace the perimeter of the small compound, but in Gill’s mind, he’s busted out. Gone. Not only from the Department of Corrections’ South Fork Forest Camp but from Oregon, the Northwest, the entire continent.

Gill’s vision takes him to the Olympic Stadium in Athens, Greece. It’s August 2004, and the crowd is coming to life as he and a stellar field launch into the final of the men’s 1,500 meters. Gill’s spikes claw the track, his Team USA shorts slap his thighs. Kids everywhere dream about winning the Super Bowl or the World Cup. Gill, a 34-year-old convicted felon serving a 70-month sentence for robbing a pizza joint, thinks about only one thing: victory in the Olympic 1,500.

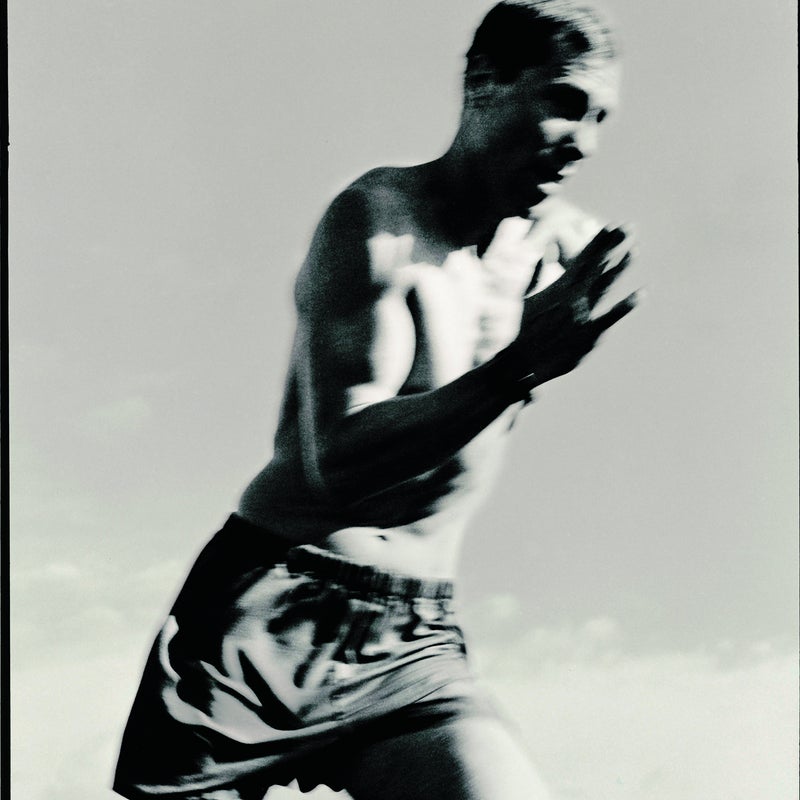

While Gill runs, I watch his form. His route comes within 50 feet of where I’m standing, just beyond the fenceless boundary at South Fork. I’ve come to the prison, 60 miles west of Portland, to see if Gill really is what he claims to be: a world-class runner, talented enough not only to make the United States Olympic team but to win a medal against the best middle-distance athletes on the planet.

Gill certainly looks good, with the bolt-upright stance and springy feet of a champion. He kicks up puffs of dust with his too-small New Balance shoes as he rips by again. He’s about an hour into his workout now, and before long he’ll have to wind down.

In Gill’s fantasy race it’s a different story: He’s fast approaching the finish line, chugging hard with 400 meters left. Morocco’s Hicham El Guerrouj, the event’s world record holder, accelerates into the lead. Gill doggedly drops into his slipstreamÔÇöa wise move in the 1,500, arguably the toughest event in track. Athletes run dangerously close to their maximum until, amid the confusion created by flying elbows, burning muscles, and oxygen-depleted brains, each runner makes a split-second decision about when to go all out for the tape. Miscalculate that breakaway and your overtaxed legs will seize so badly that you can barely keep moving.

Entering the homestretch, Gill gains a step on El Guerrouj and pulls even. He can see the finish, which the great British miler Roger Bannister once described as “the faint line…that stood ahead as a haven of peace.” With his back arched, Gill crosses the line just ahead of El Guerrouj. The crowd goes nuts as Gill pumps his fist and settles into a victory lapÔÇöthe whole glorious, melodramatic Olympic Moment bit.

Then Gill slows to a jog and, just like that, the daydream fades away. Chest heaving, he’s back inside the drab boundaries of reality: all alone in front of the South Fork mess hall.

Jonathan Christopher Gill, Oregon inmate 12520672, never hesitates to tell you that the Olympics are his destiny. “I’ve always known that I’d be a great runner,” he says, sitting across from me in the prison cafeteria. “I just had to do the work.”

It’s two hours after Gill’s morning workout. Using his finger to draw an imaginary timeline on a tabletop, he’s diagramming the beckoning path from prison cell to medal stand. First, he says, he’ll keep training hard until his release in the summer of 2003. (His sentence is up August 14.) For the next 11 months, he’ll compete in cross-country, road, and 1,500-meter events, culminating in the spring of ’04, when he hopes to post a 3:39 at a major race like the Prefontaine Classic, in Eugene, Oregon. That time would qualify him for next July’s Olympic Trials in Sacramento. There he’ll finish in the top three, and a month later it’s hello, Athens.

Gill connects the dots with an easy earnestness reflected in his schoolboyish face. His skin is line-free, his dark hair neatly combed, his brown eyes bright and eager. Six foot three and a trim, muscular 175 pounds, he sits straight as an I beam. Now he leans back confidently, cradling his head with interlaced fingers.

“I know when I get out and put that last year together,” he says, “that I’m going to make history.”

Could be. But, of course, the wiser bet is that he’ll never make it. I discovered Gill by accident back in 2001 while researching a story about American distance running, and I was quickly impressed by the depth of his obsession, which is at once inspiring and more than a little frightening. It’s one thing to think big, but can Gill possibly reach the Olympics? Just as important: What’s going to happen to him if he fails?

The short answer to the first question is yes. Ex-convicts have gone to the Olympics before: The most recent was Michael Bennett, a boxer and onetime inmate in the Illinois state pen who competed as a heavyweight in the 2000 Sydney Games. And while no track athlete has come out of prison to run in the Games, track-and-field dark horses have made Olympic teams, and they have won medals.

As for Gill, he’s not just some random con with a dream. He was born with loads of natural talent, and he used to be one of the nation’s best high school runners, winning a Michigan state cross-country championship in 1987. He missed out on a college track career, but his current coach, 65-year-old Dick BrownÔÇöa Eugene-based track-and-field legend who has trained seven Olympians, including Mary Decker Slaney and Suzy Favor HamiltonÔÇöbelieves in him completely and is convinced that the lack of wear on Gill’s legs will actually improve his chances. “This guy can do it,” Brown insists. “We’re saying, ‘Let’s get a medal.’ ”

When it comes to Gill making the team, it doesn’t hurt that American middle-distance running stinks right now. From 1983 through 2000, U.S. male runners (excluding sprinters) won only 3.4 percent of the world championship and Olympic medals in their events. Most top American times in the 1,500 were set more than 15 years ago. So an Olympic berth is ripe for the taking.

Relatively. Gill still faces enormous obstacles. For starters, he’s a recovering alcoholic, a repeat offender, and hovering on the brink of middle age. After escaping a rough upbringing outside Detroit and bolting west, Gill robbed a Gap in Pasadena in 1995. In 1997, he robbed a pizza parlor in Eugene, earning himself 70 months under Oregon’s tough mandatory-sentencing laws.

As prisons go, the 180-man South Fork facility is benign: There are no guard towers, and inmates sleep in 12-man wooden cabins without bars. But Gill has to perform hard labor every day and then train on a rock-strewn path that’s only a third of a mile long. He’s been trying for months to get transferred to an Oregon prison with better training conditions, but he’s gotten nowhere.

Meanwhile, Gill’s American competition trains in optimal settings. Athletes like Seneca Lassiter, a former NCAA 1,500-meter champion who’s almost a decade younger than Gill, and Alan Webb, a 20-year-old phenom who set a new high school record in the 1,500 in 2001, are still developing their talent. And if Gill does reach the Olympics, he’ll compete against international superstars like Kenya’s Bernard Lagat, and the great El Guerrouj. Both are capable of running the 1,500 in 3:26; Gill’s best timed mile, as a high school junior, was 4:17, which converts to a 1,500-meter time of four minutes.

Gill’s iffy chances for success led me to the second, more worrisome question: Is he prepared for failure? That one’s easy. No.

After months of conversations with Gill and people who know him, dozens of exchanged letters, and a hundred collect calls from jail, I’ve found Gill to be funny, inquisitive, and articulate. He’s also arrogantÔÇöhe tends to look down on his fellow prisonersÔÇöand he gets lost in grandiose fantasies of success that make him oblivious to the need for solid contingency plans. His attitude, which combines self-help themes with a strange sort of will to power, can be inspiring, but also dispiritingÔÇöespecially when he starts in on complaints about corrections officers, who Gill seems to think are always conspiring to thwart him.

“In this bellicose environment I have never known fear,” he wrote me early on. “[The guards] hate my audacity to shoot for the stars. Just remember in time I’ll be doing interviews on Good Morning America and living the hero’s life.”

In the end, Gill’s Olympic dream could save him, or it could just add velocity to his downfall. Many convicts, overwhelmed by the outside world’s pressures and stereotypes, lapse back into substance abuse or commit new crimes. Gill might easily slide back into his old ways, and his safety nets are flimsy.

Brown argues that Gill’s tunnel vision is precisely what will get him to the starting line in Athens. He says that typical American distance runners, who tend to be college grads with multiple options, lack the single-minded hunger that drives their usually superior African counterparts. Now look at Gill. Aside from his friendship with Brown, who’s stood behind him for the past seven years, and his relationship with two loving sisters, Gill is focused on one thing only: the 1,500.

“When Jonathan steps up to that line, he’ll look at the competition and think, They haven’t had to do what I’ve had to do to get here,” says Brown. “And he’ll think, They’re not going to take it away from me.”

Gill started running partly to get away from his family. Growing up in Detroit in the 1970s, he preferred racing around school playgrounds to facing a largely miserable cast of characters as he pinballed from home to home. There was Gill’s stint with his gypsy drunk of a mother, Mary, who disappeared when he was six, and then time spent with her alcoholic parents. There were Gill’s two years under the watch of his wealthy paternal grandparents, in suburban Detroit, where he didn’t fit in, and the high school days spent with an ambivalent father. Along the way Gill also lived with various half sisters and step-siblings, and sometimes he met members of his extended family, whom he recalls with fond nicknames like Uncle Drunky and Uncle Beat.

Gill did enjoy being with his sister, Robin, and bonded with her in the wake of their parents’ 1972 divorce. Three years younger than Gill, Robin lived in Detroit with her maternal grandparents, the Birons. In elementary school, Gill lived with them, too. He and Robin did fun stuffÔÇömaking up songs, throwing a football. But Gill paid a price, as his abusive grandmother, who reportedly also beat Mary as a child, knocked some of the happiness right out of him.

“There was a lot of taunting and name-calling,” says 31-year-old Robin, who, after years of being estranged from her brother, now lives in Portland and visits Gill weekly. “After my grandma beat him, Jon sounded like a wounded animal. To this day, the thought of that sound and how Jon must’ve been affected gets me.”

When Gill was 14, he moved in with his dad, Chris Gill, an industrial engineer living in the Detroit suburb of Ferndale. Jon lost contact with Robin, who moved to northern Michigan with the Birons. Chris had remarried, and Gill felt like a fifth wheel while living with him, his new wife, and his two stepchildren. Gill blew off house chores and says his dad smacked him. Chris, who still lives in Ferndale, admits that he sometimes struck Jon for disciplinary reasons but denies any pattern of abuse.

“Jon was always thinking, I’m going to keep pushing buttons to see if I can get him to hit me,” he says. “Obviously, he succeeded. But it wasn’t my standard form of justice.”

By the time Gill got to Ferndale High, in the fall of 1984, everything exploded at onceÔÇöhis natural running ability, his anger, and his own bad attitude. Gill pulled C’s and battled with Ferndale’s running coach, Phil Premo, who had good reason to try and look past Gill’s temperament. He’d never seen a kid with such talent.

“If I could have figured out how to get inside Jon’s head in a positive way, he could have been an Olympian,” says the 57-year-old Premo, who left Ferndale in 1992. “I’m not saying there was a possibility. That’s a guarantee.”

Premo didn’t really know how to train or control Gill, who ended up calling his own shots, turning on the juice whenever he felt like it. On several occasions, Gill infuriated Premo by building huge leads in mile races, only to turn around and taunt the field as he coasted backward to victory. (Gill denies doing this.) Premo complained that Gill simply mailed in the 4:17 mile he posted as a junior and then, during cross-country season in his senior year, came in a disappointing third at the state championships.

But Gill followed that with a performance at a state all-star meet that reminded everybody of what he could do. In a 5,000-meter race lasting some 15 minutes, he purposely dropped behind the entire field at the start before screaming, “I’ll show you who’s state champion!” Then he sprinted into the lead and won, leaving the other coaches stunned. Three weeks later, at a six-state regional meet, Gill finished a close third behind a victorious Bob Kennedy, who later competed in the 5,000 at the 1992 and 1996 Olympics.

In the eyes of most collegiate coaches, Gill’s impressive wheels couldn’t make up for his crummy GPA and unruly behavior. He accepted the only scholarship offer he got, from Ranger College, a two-year school near Dallas that Kenya’s Ibrahim Hussein had attended before winning the 1987 New York City Marathon. When Gill arrived, in 1988, he discovered that Ranger’s running program was a joke, overseen by the football coach. He left after a semester and bounced around tiny colleges in Michigan and Florida for a couple of years while missing competitions because of injuries and eligibility snags. One day in 1991, while attending community college in Gainesville, he just gave up.

“I drank a 40-ouncer and said fuck running,” Gill says. “I’m drinking beer, hanging out with chicks, and getting laid. It’s so much easier.”

Gill ratcheted up the social boozing that had started in college. He lit out for Los Angeles, where he stayed with an old high school buddy. He worked mindless jobs and pickled his ambitions with vodka, a pattern that would continue for the next five years.

Sometimes Gill tried to break out of it. In 1992, he contacted Randy Huntington, an elite track coach living in Fresno, and moved north to train. But Huntington’s expertise was with sprinters and jumpers, and Gill spent more time bartending and partying than exercising.

On December 20, 1995ÔÇöthe eve of his 27th birthdayÔÇöGill was in Southern California visiting friends when he walked into a Gap in Pasadena. Blitzed and depressed, he selected $500 worth of clothes and then told the clerk to empty the register. The police found him wobbling on the sidewalk with two stuffed Gap bags and $287. When he came to in the Los Angeles County Jail, where he eventually served six months, Gill couldn’t believe how low he’d sunk. “I knew what I was doing wasn’t what I was supposed to do with my life,” he recalls. “I had this gift and I wasn’t using it.”

Penniless, Gill made his way back to Fresno in mid-1996. Huntington was tired of the Gill soap opera, but he called an old friend in Eugene, a patient track coach named Dick Brown, who agreed to take him on. Gill didn’t know much about Brown except that he’d trained a bunch of Olympians. The night before leaving, he was so thrilled that he toasted his good fortune. And toasted, and toasted. With Absolut, all night long.

“I figured, Well, you’re going to Oregon to train, you’re finally going to become that great runner you always knew you’d become,” recalls Gill. “You’d better get it out of your system.”

Track Down Pizza, located across the street from the University of Oregon at Eugene, is a shrine to track-and-field. Many of the photos covering the walls, of great runners like Steve Prefontaine and Alberto Salazar, were shot at the U of O’s Hayward Field, the sport’s Yankee Stadium. Gill believes he’ll earn a place on the photo wall, but don’t count on seeing his face up there. Track Town was the site of the 1997 holdup that sent him to prison.

“He probably sat over there before robbing the place,” says Dick Brown, nodding toward one end of the restaurant. “Or maybe it was over there.”

It’s a day after my visit to South Fork, and Brown, sitting with a huge veggie slice in front of him, is recalling memoriesÔÇöboth good and badÔÇöof Gill’s life in Eugene.

“Jonathan entered a local 800, and I watched him from the stands. Even though he was a drunk and out of shape, I’d seen enough runners to know he could be great,” Brown says. “Jonathan’s really straight when he runsÔÇöhis torso is directly underneath him for superior leg lift and leverage. He’s also got minimal foot-on-the-ground time. His foot is like a paw that goes whoosh, moving back smooth and quick. It’s how a leopard runs.”

There weren’t many bright spots in Eugene, though. During Gill’s year there, he kept drinking and once even attempted suicide, swallowing a bottle of sleeping pills. Brown tried to help. He got Gill jobs, sent him to AA, and called 911 for the emergency stomach pump that saved Gill’s life. But nothing set him straight.

At six foot five, with huge forearms and long legs, Brown looks like a bruiser, but he’s actually a big softy, both on and off the track. His partner, Marlene Wellborn, whom Brown calls his “shit detector,” thought he was nuts for endlessly propping up Gill. But Brown believed he could gently turn him around. He’d gotten great performances from the oft injured and mercurial Mary Decker Slaney, who won two world championships while working with Brown, and he’d sent an extraordinary 23 athletes to the 1984 L.A. Olympics as director of the Athletics West running team. In Gill, Brown saw similarities to Steve Scott, a big, strong middle-distance runner who powered his way past wispier athletes and onto three Olympic teams in the eighties and nineties.

Gill knew Brown was a potential savior; he just couldn’t respond. “Train all day and then work a job was a whole new concept to me,” says Gill. “I thought nighttime was for Michelob.”

Drunk and wearing a Detroit Lions cap when he walked into Track Town in the early hours of October 4, 1997, Gill rested a backpack on the countertop, with his hand inside. “I’ve got you covered,” he said to the kid behind the register. “Open the till.” He walked away with $225 and was arrested several days later.

When Gill got an unexpectedly harsh sentence of nearly six years for armed robberyÔÇöhe wasn’t armed, but pretending to have a gun counts the sameÔÇöBrown reassured him that the dream could live on. “I won’t give up on you until you give up on yourself,” the coach said.

It took 14 months for Gill to bottom out. He spent six months in Lane County Jail, near Eugene, and then got transferred to eastern Oregon’s harsh Snake River Correctional Institution, where he squabbled with guards and fought with other convicts. One day, he refused to enter his cell and was slapped with a 120-day sentence in solitary confinement. Around the time of his 30th birthday, sitting alone in an eight-by-ten-foot concrete cage, Gill meditated on Brown’s faith in himÔÇöand on his own unrealized potential.

“I thought, You’re either going to take a hard look at yourself now or you never will,” he says. “You’re going to come out of the hole an athlete or you’re going to quit promising this to yourself, because it’s tearing you up. If you commit, that means you’ve got to do everything.”

Gill decided to commit. He performed endless push-ups and squats in his cell, swore off drinking, and started reading about people like Muhammad Ali and Jesse Owens, “free thinkers like myself, since I’ll go from being a convict to an Olympian.” In time Gill would get a letter from a half sister, Jessica Brown, who lives outside Chicago, and a note from Robin, who had ended up in the Bay Area. He replied with news of his fresh start, and the supportive mail kept coming.

A few days after his big epiphany, Gill stepped into a snow-covered pen enclosed by 30-foot concrete walls for one of his few weekly exercise breaks. Dressed in an orange jumpsuit and blue rubber slippers, he started running. The cage was three strides wide, eight strides long.

“Envision!” Gill thought to himself. He imagined hearing a coach shout times as he ran: “Fifty-six for the quarter-mile.” Adding speed, Gill grooved a path and practically bounced off the walls. Soon the skin on his feet cracked, and blood from his cuts turned the snow pale crimson.

But Gill wouldn’t stop. “Fifty-six!” he heard, and then said to himself, “I’m on pace! I’m on pace!”

Gill arrived at South Fork┬áin August 2001. That spring he’d secured a transfer from Snake River, where he had begun training on a cramped 200-meter track. (A standard oval is 400 meters.) He spent the summer battling wildfires at a prison firefighters’ outpost in the Oregon woods, and at South Fork he settled into a daily regimen that mixed the routines of prison life with a grueling fitness program devised by him and Brown.

The South Fork wake-up bell rings every weekday morning at 5:30. Gill usually skips breakfast to sleep in, and makes his own meal inside the cabin with food purchased at the prison canteen. Downing a concoction of hot water, wheat germ, and honey, he slips into work boots and by 7 a.m. reluctantly piles into a white prison van with nine other convicts. For $1.50 a day, each inmate does seven hours of hard labor, pruning trees or trapping beavers for the Oregon Department of Forestry.

The van arrives back at South Fork around 3:15, and Gill’s Olympic training begins. He sprints to the cabin to change into the cheap $30 running shoes he buys at the canteen. Then he endlessly orbits the camp, running intervals, performing drills, or just logging ten solid miles before returning to his cabin at 4:30. At 5:30 he eats dinner in the dingy chow hall. Then, while the other convicts watch the hotties on Temptation Island, he does 1,500 sit-ups and pumps iron in a tiny weight room from 7:30 to 8:30. Finally, he jumps up and down on an 18-inch-high wooden box for an hour to strengthen his hip flexors, which aid in lifting a runner’s legs.

When Gill finishes, he tiptoes past sleeping cabinmates and turns on a small light over his bunk. He looks at the clippings neatly taped to his closet door. There’s an Abe Lincoln quote (don’t count the days, make the days count), an action photo of El Guerrouj, and a picture of Greek ruins with a caption reading, clock ticking on athens. Then he turns out the light.

Because Gill’s schedule changes with new labor assignments, Brown gives him general training guidelines rather than fixed routines. The coach’s immediate goal for Gill, however, is clear-cut: Develop endurance. The better Gill’s muscles become at synthesizing oxygen, the faster he’ll be able to run in a 1,500-meter race before going all out at the finish. High-impact sprint training, Brown says, can wait until after Gill’s release.

Most elite runners don’t work nearly this hard. The typical training routine for a top distance athlete includes two daily runs, occasional weight workouts, some stretching, big naps around midday, and plenty of healthy food. The average Olympian would grumble over Gill’s standard dinner fareÔÇöa skimpy 900-calorie veggie tray supplemented with all the ramen, sunflower seeds, jerky sticks, and spreadable cheese that he can afford to buy from the canteen.

Gill claims that the daily hardships galvanize both his mind and body. “If you think that lactic burn is the worst pain you can endure in life, you’re wrong,” he says. “There will never be a race as hard as some of the things that I have to deal with.”

It all sounds appropriately Rocky-esque, but can it work? Nobody can predict that, but when I start telling people in the track world about GillÔÇönone of them has ever heard of himÔÇöthe response is nearly uniform. They admire the resolve, but they seriously doubt he’ll get anywhere.

“Not enough sleep, no massages, cheap shoesÔÇöit all adds up,” says Steve Holman, 33, the former U.S. 1,500-meter champ-ion. “Why doesn’t he just use the running to help him straighten out his life?”

“Wishing is great, but this guy is old,” says Brooks Johnson, 69, who’s coached American runners at every Olympics since 1968. “I’d root for him, but you’ve got people just as talented as Jon but without the handicaps and in their biological prime.”

Gill fires right back when he hears these assessments. He mentions the “old” track athlete Regina Jacobs, who at 39 recently set a world record in the women’s 1,500. Meanwhile, he doesn’t think much of his younger competition. He’ll tell you that only one American, Jason Pyrah, reached the 1,500-meter final at Sydney, and that he finished at the back of the pack.

“When is everyone going to figure out that it’s all about hard work and desire?” Gill says.

That sounds like Rocky again, but hard work has paid off for Kenyan runners, who credit much of their success to pure effort. One outsider who doesn’t shrug off Gill’s chances is Henry Rono, a 51-year-old Kenyan living in Albuquerque, New Mexico, who broke four different world records in 1978, dominating everything from the 3,000 to the 10,000.

“I told people in 1971 that I was going to break records, and they thought I was crazy,” says Rono. “But I was determined. Jon could be one who is so hungry.”

Gill is definitely hungry. So hungry that he keeps running even after silver-dollar-size blisters bubble up on his feet. So hungry that he inspires admiration in the very prison population that he disdainfully refers to as “the lumpenproletariat.”

“Many guys respect Jon and go out of their way to acknowledge him,” says Dennis Harrison, a 53-year-old inmate who has befriended Gill. “The guys who don’t like Jon are resentful. They can’t be happy about someone trying to break free.”

Four days after my visit to South Fork and Eugene, I’m feeling pretty optimistic about Gill. He and Brown are right. They can pull this off. And then, within 24 hours, my feelings are thrown in reverse, and I’m reminded that I’m dealing with a troubled soul who can’t always be trusted.

Gill calls in the late afternoon. I usually enjoy our conversations, because once you get past the heady dream-speak, he’s downright affable and eager to talk about anything from the Detroit Lions to Copernicus. But today he’s no fun at all.

“It’s snowing,” he gripes. “We got dumped on yesterday, and it’s still coming down. If I drop the hammer out there and get hurt, I’ll be pretty pissed.” The bleak conditions also remind him of a hurdle he can’t quite clear. Despite months of inquiries, he hasn’t heard anything from South Fork’s officers about his request to transfer to Santiam Correctional Institution. Located down south in Salem, Santiam offers warmer weather and a 300-meter track. It’s also close to Brown’s home, in Eugene. For Brown, visiting Gill at South Fork is a six-hour schlep that he’s managed only three times.

Gill takes the delay personally. “They don’t want to help me with my dream,” he says. “They want to see me fail.”

So, as I would later learn, Gill decides that if he can’t transfer, he’ll make South Fork more livable by bartering to satisfy his constant hunger. He and two other convicts will arrange for a “drop”ÔÇöan illegal acquisition of contraband that he can trade to inmates for extra canteen food.

Gill makes plans to have an old acquaintance from Portland drive out and leave a stash of chewing tobacco in the woods beyond the South Fork boundaries. But before an accomplice can sneak out and grab it, someone snitches.

This infraction costs Gill 30 days in the hole at the medium-security Oregon State Correctional Institution (OSCI), in Salem. While serving the sentence, he keeps on with his routines. He runs barefoot in a small pen and does push-ups in his cell. He grabs a dictionary of Latin words off the prison book cart and mines it for sayings.

“I can’t dwell on how I could have avoided this,” he writes from OSCI. “Instead, this is my last monastery before my steadfast drive to the Olympics…This is my time to work on my shortcomings and tone down my Cool Hand Luke defiance.”

He signs the letter, “Dum spiro spero (While I breathe, I hope), Jonathan.”

Though Gill’s act was unbelievably stupid, his resolve gnaws at me. He has admitted weakness, which he seldom does, and continues to train. The botched crime might actually help Gill, since it’s a wake-up call. It also defines him as a risky inmate at South Fork, which, oddly, could work to his advantage. After leaving solitary, he will ultimately be sent to a different minimum-security facility. Maybe he’ll land somewhere with a decent track.

I call Brown, who says he’s just about had enough. “If this happens one more time,” he says, “I’ll consider that Jonathan has given up.”

The bleakness lifts around the time spring arrives. A month after Gill gets out of the hole, in April 2002, he calls me with an update. “Aloha, Andrew,” he says happily. There’s a long pause, and I think we’ve been cut off. But Gill is just savoring the moment. “I just got transferred to Santiam.” Dum spiro spero. Damned if one of his wishes hasn’t come true.

In Gill’s mind, the dream seldom turns ugly. He doesn’t think about finishing last or falling off the wagon, though he should. Ask him to contemplate life without making the Olympic team and Gill offers half-baked contingency plans. He could become a motivational speaker or a sports agent. Perhaps a coach. Brown is trying to create a foundation that funds promising runners willing to focus their lives on Olympic and world championship medalsÔÇömaybe there could be a staff position for Gill. But so far Brown has signed up only one athlete and raised less than $150,000 of his nearly $3 million goal.

“Dick just needs a real mouth to sell the foundation,” Gill says. “I could be that mouth. What’s a salesman if not a little bit of a con man?”

That sounds smooth, but, unfortunately, clever talk and self-confidence don’t get you far on the outside.

“Ex-offenders think they’ve weathered the worst and that they’re ready to face any challenge,” says Richard Stratton, who once served eight years for dope smuggling and is the creator of Street Time, a Showtime drama about ex-cons. “But freedom is disconcerting. Life is black-and-white in jail. The outside world is gray. You can feel overwhelmed and depressed.”

Gill has lined up shelter and foodÔÇöhe’ll stay with Brown before moving into an apartment, living off a stipend that Brown thinks he can round up from Eugene’s wealthy, running-crazed businessmenÔÇöbut he will still have to deal with daily life and its thousands of small challenges. Even if he makes it to the track, his enormous goal could weigh him down.

If he has enough rough days, Gill’s old ally, the bottle, awaits him at every turn. His brazen attitude toward his disease is unsettling; he’s announced on several occasions that AA is out of the question. “Why do I need someone telling me, ‘Don’t drink, because it’s bad’?” he says. “I know that. I control my mind and just tell myself drinking’s bad.”

That confidence could hurt him. “We find that ‘master of my own destiny’ attitude in a lot of doctors, lawyers, and professional athletes who’ve mastered something and think they can stay away from alcohol,” says Dr. Anne Linton, the chief medical officer for the Betty Ford Center, in Rancho Mirage, California. “At some point, they won’t be getting the career accolades, yet they still want to feel good. Alcohol is an easy way to do that.”

Amid such pitfalls, the only person who seems to be wisely bracing for Gill’s release is his sister, Robin. “There are too many ‘ifs’ with Jon,” she says. “If the training goes well. If Dick gets Jon a place to live. I’m wondering, What’s going to happen for sure?”

Emerging from a childhood as troubled as her brother’s, Robin moved west, abandoning her past. In 1996, she graduated from the University of New Mexico with a bachelor’s degree in anthropology, and ultimately landed in Palo Alto, California, where she worked in a public library. Only in 2001, 15 years after last speaking to Gill, did she seek him out.

“I love my brother. I know that sounds weirdÔÇölike ‘Why did you disappear?’ ” she says. “But I wasn’t strong enough to handle my own problems. His story is extremely painful, and I couldn’t deal with it.”

After the two first talked, Gill was so excited that he wrote robin on both sides of his hand. “There’s all this feeling in my heart that I haven’t had,” Gill says. “I also have someone around to confirm the hell that I went through.”

In February 2002, Robin moved to Portland to be closer to Gill. She holds a couple of social-work jobs, takes classes, and visits Gill every Saturday, buying him cinnamon rolls out of a vending machine. They blab about family and nasty prison guards, and sometimes the conversation turns to how Gill will furnish his apartment. The talk makes Robin uncomfortable. She barely makes ends meet herself.

“Where will Jon get money for underwear or a toothbrush?” she says.

Gill sees no need for worry. “With my pending success, endorsements for shoes and sunglasses should come relatively quickly,” he says. “Maybe I could use some of the money to help pay for Robin’s education. Or someday get her a Lexus. I think that would suit her tastes.”

The concertina wire┬ásparkles in the Oregon rain. It’s March 2003, and Gill’s legs churn through the heavy air as he runs on the track at Santiam. The circuit is far from perfectÔÇömore rectangular than oval. Unfazed by the tight turns, Gill sails past a few joggers en route to another speedy lap. He calls Santiam his “East German training compound.” The dream has never shined brighter.

“Whether it was luck or serendipity, I’m here. Actually, in my mind I believe it’s destiny,” he told me after first arriving at Santiam. “There was a Berlin Wall that I had to go through, and I went through it. I’m finally where I want to be.”

Just now, I’m with two other observersÔÇöGuy Hall, the prison’s warden, and Dick BrownÔÇöwatching Gill run.

When Gill first came to Santiam, in the spring of 2002, he saw Hall in the rec yard. “Gill walked up to me and said, ‘You don’t know me, but my name is Jonathan Gill and I’m a runner, and I’ve got this dream and this coach,’ ” says Hall, pushing back the hood on his jacket. “This was all in the first 30 seconds. First thing that pops into my mind? Classic manipulator. But when I checked him out, he was sincere.”

Hall, a trim 51-year-old fitness buff, appreciated Gill’s goal. He started a prison running club to get other inmates exercising, and made Gill secretary, which still leaves him eight hours a day to train. When Gill isn’t running, he’s answering members’ questions or writing thank-you notes to guest speakersÔÇöamong them, Dick Brown. Brown drives from Eugene to Salem every month to talk to the 30-man group and watch them run. Just now he’s watching Gill. This is the first time in years that he’s had a chance to see a healthy, fit Gill burn rubber.

“His hips aren’t sagging. He’s up nice and straight,” Brown says with enthusiasm. “His feet pop.”

Gill slows to a stop in front of his coach.

“What’d you think?”

“You had good turnover. But you need to work on your arms.”

“Really…”

The discussion continues from there, and I think about how, very soon, it’ll move 60 miles south to the track at Hayward Field, which will be Gill’s home turf.

After his release, Gill will build up his speed in the late summer and maybe trot through a 5K. He’ll enter fall cross-country and winter indoor-track eventsÔÇöBrown calls them “experience races”ÔÇöjust to get a feeling for competition. Come 2004, Gill will try to qualify for the Olympic Trials at Stanford’s Cardinal Invitational or the Prefontaine Classic. There he’ll face some of the nation’s best, runners like Alan Webb, although Gill expects Webb to continue to crater in the wake of a brief and disappointing college career.

“I’ll go on record as saying that for Alan Webb, his high school years were as good as it’s going to get,” says Gill.

In the Olympic Trials, Gill predicts that he’ll run under 3:35. At the Olympics, he’ll boldly move to the front, where he couldn’t care less about the clock. “I’m not running for a time in Athens,” says Gill. “I’m running to win.”

There’s no point underestimating a man who’s convinced he has incredible powers. All you can do is acknowledge his dreams, stand back, cross your fingers, and wonder if the rest of us get stuck too easily in our mundane grasp of reality.

“Maybe we can’t fathom the human limits,” Gill once told me. “MaybeÔÇöand this sounds out thereÔÇöbut who’s to say that we can’t telecommunicate? It might be feasible. Instead of saying, ‘The whole world is just like this,’ why not think the other way around? Why not believe that nothing is impossible?”