IN EARLY FEBRUARY, roughly a thousand miles south of Algiers in the Sahara, European adventure travelers started disappearing without a trace. By mid-April, 15 Germans, ten Austrians, four Swiss, a Dutchman, and a Swede—an astonishing total of 31 men and women—had simply vanished into the void.

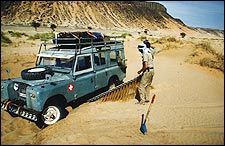

Left behind: an abandoned vehicle on the Grave Route in Algeria, April 2003

Left behind: an abandoned vehicle on the Grave Route in Algeria, April 2003

About the only thing these unlucky travelers left behind was a single vehicle in an archaeologically rich stretch of southern Algeria known as the Grave Route. At press time, after a massive hunt that included more than a thousand searchers—some on camels, some in helicopters equipped with heat-detection equipment—17 of the travelers had been liberated by Algerian commandos during a rescue operation near the Libyan border. A second rescue mission was reportedly being organized. Observers were not yet able to confirm the identity of the abductors (no group claimed responsibility), but speculated that they were part of a militant Islamist organization known as the Salafist Group for Call and Combat, which the State Department suspects has links to Al Qaeda. The motive? One theory was that the kidnappings were part of a plan to negotiate the release of four Algerians recently convicted of plotting a terrorist bombing in Strasbourg, France. Ordinarily, a mass disappearance of this magnitude would make front-page headlines around the world. But this story was lumped in with a broader convergence of bad news that served to heighten widespread anxiety about the safety of international travel. The war in Iraq, the ongoing threat of anti-American terrorism, and the outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) transformed the jitters of early 2003 into unmitigated fear. In late April, a survey by the Travel Industry Association of America showed that 71 percent of U.S. citizens had decided that, thanks all the same, they would rather vacation on the home front this year. Many travel companies reported that SARS had caused an alarming drop in overseas bookings. The impact has been most severe in Asia, where the bulk of SARS fatalities have occurred. As news of the epidemic spread, flights on Pacific routes plummeted 38 percent, a devastating economic loss in a region that was fast becoming a tourism hot spot.

So is it time to forget your dreams of adventure and stay put? Not really. Obviously, now is not the best year to head for Algeria or southern Iraq. But despite reasonable concerns about security and the course of the SARS outbreak, the latest travel panic is largely unjustified. In fact, for adventurous types inclined to gripe about crowds overrunning the world’s last best places, the next few months could shape up as a singular opportunity to thumb your nose at paranoia and express the basic human right to wander and explore.

By most measures, the current mass aversion to travel is far out of line with actual risks. In 2002, the odds of an American civilian dying in a terrorist attack were one in nine million, while the odds of dying in a traffic accident in the United States were one in 7,000. Worldwide, the risk of dying from SARS is even smaller. And there may be a silver lining in the current cloud of gloom: Right now, adventure travel bargains are available everywhere as outfitters strive to regain momentum. Airline fares are at a 14-year low, and the cost of lodging and travel packages is steadily dropping. In the spring, many flights to Europe were less than $500; Caribbean airfares were under $400; a week in Chamonix, including flights, was going for $900. There are even bargains for elite climbers: Pakistan recently waived all climbing fees for peaks under 6,500 meters and cut fees in half for taller mountains.

AS THE SITUATION SHAKES OUT, some intrepid travelers are hedging their bets by planning domestic trips and saving exotic destinations for later. Mountain Travel Sobek reports that reservations have been lower than average overall but that bookings for North American trips have jumped 42 percent over the past year. “This season, a lot of people are going to stay closer to home and take driving vacations,” says Jerry Mallet, president of the ���ϳԹ��� Travel Society. “But travelers are pent up and getting tired. I think eventually people are going to travel again.”

On the international front, some hardcore outfitters and their clients argue that the Great Panic of 2003 is mostly a reflection of an urban mind-set and a stampede toward zero-risk timidity. Savvy adventure travelers typically blow through cities on their way to the good stuff and do their homework first. (The European trekkers who disappeared in the Sahara apparently had not recruited seasoned guides to accompany them, in an area known for lawless activity.) An informal survey of adventure travel companies by ���ϳԹ��� found that most diehard adventurers are unfazed by world events. “Our folks—the adventurous clients—are still going,” says Robyn Gorman, marketing director for Mountain Travel Sobek. “They’re much more attuned to the rest of the world than the average traveler.”

This attitude is justified—in most destinations, the locals are still more interested in collecting dollars than defending political ideologies. “The average person in other countries is concerned with putting food on the table,” says Robert Link, founder of the adventure travel company Mountain Link. “They couldn’t care less about nationalities.”

And while terror is always a concern, Tom Sanderson, an international-threat analyst at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, in Washington, D.C., says, “I wouldn’t panic or cancel trips. You just need to stay away from certain areas.” Those areas include trouble zones like Pakistan, Colombia, Afghanistan, and portions of the Middle East.

Luckily, there have been few significant attacks since 9/11—and no terror incidents on U.S. soil in the past 20 months. But the threat is still there. “The huge U.S. presence in Central Asia and the Middle East is not sitting well with many people,” Sanderson warns. “There’s definitely the potential for terrorism to get worse.”

It’s also difficult to predict the future of SARS. “I can’t say whether it’s going to peter out or spread or come back next fall,” says Steve Ostroff, deputy director of the National Center for Infectious Diseases, in Atlanta. “Even if you damp down or stamp out the clusters of illness that have come about, you always run the risk that it could be introduced over and over again.” At press time, the World Health Organization was optimistic that the disease had been contained in most countries, though, predictably, they urged caution in Beijing and Hong Kong.

Terrorist threats, anthrax, violent conflict, recession, anti-Americanism—getting things back on track seems like a big task. On the other hand, anyone who thinks that history won’t take unexpected U-turns hasn’t been paying attention. It’s worth noting that geopolitical hot spots of decades past—Nicaragua, Vietnam, South Africa, most of Eastern Europe—have become friendly tourist destinations for U.S. travelers. Who knows? In ten years, Iraq’s Persian Gulf port of Umm Qasr could be hosting a beach volleyball tournament.

No matter how bad things get, the urge to travel won’t disappear, even if it takes us to not-so-distant ports of call. Almost two years of apprehension, vague dread, and sheer frustration may be what ultimately gets the ball rolling again. “There have been a lot of people jumping on the fear wagon as far as adventure travel goes,” says Robert Link. “People think the world is falling down around them. But that’s just not the case.”