OUR INNER APE

A Leading Primatologist Explains

Why We Are Who We Are

By Frans de Waal

(Riverhead, $26)

THE APE IN THE CORNER OFFICE

Understanding the Workplace

Beast in All of Us

By Richard Conniff

(Crown Business, $25)

HUMANS HAVE NO CLOSER evolutionary cousin than chimpanzees—we are, in fact, 98 percent genetically identical—and for more than a quarter-century Dutch primatologist Frans de Waal has been unlocking the uncanny parallels between their behavior and our own. His classic Chimpanzee Politics (1982), based on observations of chimp interaction at a Netherlands zoo, detailed charging, temper tantrums, and coalition building so similar to the acts of human politicians that the book has been hailed as a power primer on the order of Machiavelli’s The Prince. Newt Gingrich even recommended the title to incoming Republican congressmen in 1995.

In Our Inner Ape, de Waal all but apologizes for the success of Chimpanzee Politics and similar books published by researchers in the eighties and nineties. “The chimpanzee demonstrates the violent side of human nature so well that few scientists write about any other side at all,” he explains, lamenting that this selective focus has wrongly positioned violence as the defining trait among primates—including us. To broaden that view, de Waal draws on his studies of bonobos, chimp cousins that live on the south bank of Africa’s Congo River. As much as chimps employ violence, he explains, these “Kama Sutra primates” employ sex. Bonobos live in matriarchal, egalitarian societies and are more likely to make love than war, leading de Waal to believe that chimps—and humans—are genetically programmed not just for aggression but for empathy, compassion, and peacemaking. It may not be stretching things too far to talk about “survival of the kindest,” as de Waal does here.

Like de Waal’s previous books (including Bonobo, 1997, and The Ape and the Sushi Master, 2001), Our Inner Ape is filled with fascinating examples of how human behavior can be explained by our ape ancestors. While we save French kisses for our most intimate partners, for example, bonobos slip each other the tongue to signal friendship and bonding. For them, de Waal explains, “tongue kissing… is an act of total trust: The tongue is one of our most sensitive organs, and the mouth is the body cavity that can do it the quickest harm.” And just as male primates use “charging displays” to establish dominance when encountering strangers (drumming loudly on anything they can find, standing their hair on end), newly introduced humans also struggle to clarify who’s who in the social hierarchy. But men tend to do it, de Waal writes, “in the more civilized manner of making mincemeat of someone else’s arguments or, more primitively, giving others no time to open their mouths.”

Richard Conniff isn’t a primatologist, he’s a journalist and author of The Natural History of the Rich (2002). But if Conniff’s new book, The Ape in the Corner Office, is any indication, de Waal’s emphasize-the-nice campaign is already taking hold. Citing the work of de Waal and other animal behaviorists, Conniff deftly, and at times hilariously, wraps discoveries from the primate world around real-life examples taken from corporations like Intel, Enron, and Nike. Rejecting the implications of the old “business is a jungle” metaphor, Conniff explores the ways managers and businesses can thrive by using “prosocial dominance”: gaining power by making friends, building alliances, and deploying forces like compromise and persuasion—just as bonobos do. After years of bitter and very public rivalry, Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer and Sun Microsystems chief Scott McNealy made peace in 2004 when they realized their feud had become a dangerous distraction. “When high-ranking chimps fight,” Conniff notes, recalling observations made by de Waal, “even bystanders suffer palpable tension.” It’s still a jungle out there—Conniff’s not disputing that—but it’s a kinder, gentler jungle. “Being nice, nurturing other people, and being nurtured by them,” he concludes, “is as necessary to us as breathing clean air.” —Bruce Barcott

Shaken to the Core

“It made its entrance in a spectacular, horrifying, unforgettable way,” Simon Winchester writes of the magnitude-8.25 earthquake that wracked San Francisco in 1906. “It came thundering in on… huge undulating waves… great buildings rose and fell, rose and fell, in what looked like an enormous tidal bore, an unstoppable tsunami of rock and brick and cement and stone.” This description, from Winchester’s A Crack in the Edge of the World: America and the Great California Earthquake of 1906 (HarperCollins, $27), may be the most gripping account of a temblor ever written. But the author of bestsellers Krakatoa (2003) and The Professor and the Madman (1998) has created more than the literary equivalent of a disaster flick. Winchester makes you work for the drama, interrupting details of the tragedy with chapters on geology, the great quakes of the past 200 years (including the one that triggered last year’s Indian Ocean tsunami), and the founding of San Francisco. When he finally delivers his blow-by-blow of the quake that killed more than 3,000, it feels all at once like a ghastly human tragedy, a staggering freak-show spectacle, and a turning point in our scientific and cultural understanding of the planet. —Daniel Duane

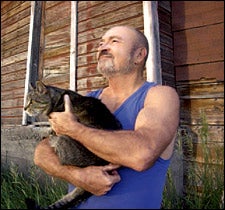

HAYDUKE SPEAKS

In his 1975 classic The Monkey Wrench Gang, Edward Abbey gave us George Washington Hayduke—a restless, angry, boozed-up Vietnam vet who roamed the Southwest with a motley band of eco-saboteurs. Thirty years later, Doug Peacock (below), Abbey’s real-life model for Hayduke, shares his side of the story.

Walking It Off: A Veteran’s Chronicle of War and Wilderness (Eastern Washington University Press, $20) is a passionate reflection on his life as a war-scarred environmentalist and bear watcher; his treks in Nepal and Mexico; and his prickly friendship with Abbey, whom he ultimately forgave for the semi-unflattering (if honest, he admits) caricature. “My most trusted guides so far in life?” he writes. “I could do much worse than Ed, that horny, crabby old fart, much like the grizzlies I so loved.” (Some of the book appeared previously in ���ϳԹ���.)