NEVER MIND THE NICE WEATHER, or anything else outside. We’re looking inward, toward the center of a vast exercise floor in Boulder, Colorado’s Flatiron Athletic Club. In what is arguably the premier workout facility in the world’s fittest city, 30 of us are prostrated at the feet of Peter Seamans, a 46-year-old bodybuilder, personal trainer, and Mr. Clean look-alike who calls himself the Iron Yogi.

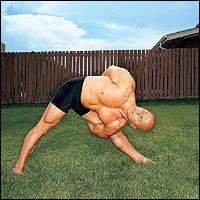

INCREDIBLE BULK: The Iron Yogi plants a tree pose in a Boulder, Colorado, emporium.

INCREDIBLE BULK: The Iron Yogi plants a tree pose in a Boulder, Colorado, emporium.Peter Seamans

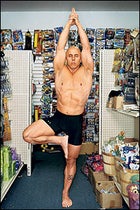

THIS IS SPINAL TRAP: Seamans gets twisted across the street from Boulder’s Flatiron Athletic Club.

THIS IS SPINAL TRAP: Seamans gets twisted across the street from Boulder’s Flatiron Athletic Club.

Seamans’s gladiator shoulders bulge under his black spandex tank top. His massive legs—the left shin adorned with an om-symbol tattoo—sprout from similarly clingy black spandex leggings. His pupils seem dilated, as if he’s so pumped about his mission that he’s fully transcending the here and now. The Iron Yogi—all five foot six inches and 190 pounds of him—is leading his trademark yoga course, Turbo Vinyasa, and he can’t wait to take us with him to the next level. But first he’s got to turn down the cranking electronica remix of Carmina Burana.

Silence. “Everyone up against the wall,” he commands.

Students quickly drag their yoga mats to the outer edge of the wood floor.

“Four inches apart!” he bellows. “Facing me, assume neutral table.”

Thirty adults drop to their hands and knees like dogs. Some of us are regulars—weight lifters, marathoners, triathletes, matrons with performance-enhancing divorce settlements. Others are unsuspecting newbies who might soon wish they’d followed the lead of the middle-aged guy who, broken by the pain, rolled up his mat and sneaked out a few minutes ago.

“Now push to dolphin,” Seamans orders.

Obediently, we strain into a steep pike off our forearms, then walk our feet up the wall so that our bodies form L shapes, pressing toward inhumanly upside-down poses. Shoulders quiver. When the Iron One launches us from there into pincha mayurasana—a head-down, feet-skyward forearm stand that traditional yogis don’t recommend for intermediate students, let alone beginners—the yelps are audible. One by one we all collapse—some gracefully, others on their heads.

A skinny man, who bonked early and often, crumples onto his back, eyes glazed over in a thousand-yard stare. That guy won’t be returning, I assume, as he staggers out the door. But next week he shows up again, contorting himself into a trembling tangle of pain. Just like me, come to think of it.

All of which raises a question that, for ages, has vexed seekers of health and enlightenment: Must we truly feel the burn?

IT’S HARD NOT TO ASK THAT when you’re an hour into one of the most athletically demanding forms of yoga in the United States. Created three years ago by Seamans, Turbo Vinyasa is the latest entry in a crammed field of yoga spin-offs whose inventors hope to make millions—and whose evolving methods look less and less like yoga and more like some supercharged, over-amped Yank mutation. Yoga meets pro wrestling.

Seamans’s routine, for one, is a fast-paced, excruciating series of poses uniquely suited to avowed jocks and anyone else who craves that near-death feeling. The physical exhaustion, coupled with a brief visualization at the end of class, can lead devotees to his brand of transcendence, Seamans says.

“I want my students to have the shittiest day,” he explains. “They ran over the dog in the driveway, found out they didn’t have a job when they got to work, came home and heard their mother has terminal cancer. I want them to experience all that, and then come to my class and be able to see the magic in life.”

To that end, each 90-minute session starts with a 15-minute warm-up that morphs into an hourlong regimen designed to boost stability, flexibility, strength, and muscle tone, plus “reverse the aging process,” Seamans says. (It won’t give you muscles like the Iron Yogi’s, though; for that you have to add weight lifting.) Seamans doesn’t soothe students with serenity-speak or hector them about breathing techniques. Instead, he whips them through killer poses, like the leg-lifting urinating dog and the one-armed-push-up wishbone, done almost at the pace of aerobics. Should someone someday complete the class perfectly, Seamans vows to make it harder.

Sounds awful, but Seamans has plenty of fans, and his yoga style is the club’s most popular. “I love it—everyone does,” says 43-year-old Evelyn Dale, a 117-pound class regular who can squat her own body weight 12 times for ten consecutive sets. “We’d threaten his life if he ever said he was going to leave Boulder.”

Seamans, meanwhile, grandly says his goal is nothing less than to save lives. “I want people to get to the point where there’s nothing they can’t do,” he says. Turbo Vinyasa, he believes, can lead to connectedness and empowerment, a real-life kick in the karmic pants for millions of downtrodden chubbies.

“Eric!” he ranted to me one day inside the sterile beige gym office that he shares with other Flatiron trainers. “I feel like I’ve got the golden bullet, the magic cure, and I need to spread it—Billy Graham style!”

MESSIANIC QUALITIES ASIDE, Seamans’s talents are firmly based in reality. Vogue voted him one of the nation’s top 50 personal trainers in 1996; former clients include enlightenment mogul Deepak Chopra and motivational maestro Anthony Robbins. He’s a champion drug-tested (read: non-steroid-using) bodybuilder who won the 40-and-over masters division in California in 2001. He’s also a certified instructor in nutrition, massage, anatomy, physiology, exercise science, movement studies, and, lest we forget, yoga.

And Turbo Vinyasa—if all goes well—just might go global. This month, Seamans is advertising his teacher-training courses with a blitzkrieg of press releases sent to fitness centers from Costa Rica to Canada, in hopes of developing an international client base. He’s also making two DVDs about his methods, and writing a book, The Tao of the Iron Yogi: Tuning the Human Instrument, Mastering the Human Experience, and Finding God in the Human Race, which he says he may publish himself. His business plan: to fill the void between what he calls “superficial health-center yoga” and “press-a-ruby-into-your-forehead, stinky-vegetarian yoga.” Turbo Vinyasa squarely targets overachievers and gym-going men—two of the largest untapped demographics in the ever-expanding yoga universe.

Fifteen million Americans regularly practice some form of yoga. In the next 12 months, according to a 2003 Harris poll, 35 million people—many of them men—are expected to try it for the first time. Already, some 85 percent of U.S. fitness facilities, from YMCA to Crunch, offer yoga classes—more than double the percentage in 1995. And demand is growing, particularly for extreme, testosterone-addled yoga, the kind packaged with the words Power or Hot or, well, Turbo.

“Americans like a hard, sweaty yoga practice,” says Hillari Dowdle, editor in chief of Yoga Journal, the Berkeley, California–based bi-monthly. “They like it to be exercise.”

Seamans knows this is his hook but wants to make clear that there’s bliss to be had as well. “Some gal, maybe 40 pounds overweight—was a cheerleader but then had three kids,” he says, spinning one of his many transformation parables. “You watch that housewife hit the bird of paradise on the first try! She never thought she could, but she’s been breathing, moving, sweating, producing endorphins, and then she looks up and sees her leg above her head and says, ‘Ho-leee shit!’ That’s the magic.”

WHEN YOGA WAS CREATED, in India some 5,000 years ago, holy-shit moments weren’t exactly what the ancients had in mind. A sacred belief system that branched into a variety of forms, its most popular offshoot in the West, hatha yoga, focuses on posture and breath control as a way to know God.

A Russian-born woman with the chosen name of Indra Devi opened America’s first hatha yoga studio, in Hollywood in 1947. Patronized by Olivia de Havilland and Gloria Swanson, Devi began the tradition of teaching celebrities about forces more powerful than their own publicity. By the 1970s, yoga had gained much broader exposure, and a few savvy yogis began tweaking the ancient formulas, giving the practice its first modern marketing twists. Bikram Choudhury’s superheated yoga—26 poses performed in a 110-degree room, the better to loosen your muscles—debuted in Beverly Hills in 1972, and in recent years became such a craze that Choudhury built a franchise. Today, with 314 certified schools worldwide—and a fleet of Rolls-Royces and Bentleys in his garages—Bikram Yoga rakes in some $7 million a year.

By the 1980s, Beryl Bender Birch had created the immensely popular Power Yoga, with a routine designed especially for skiers and runners. Baron Baptiste—whose father, Walt Baptiste, was Mr. America 1949—scored a similarly big hit when he combined vinyasa-style yoga (involving a near-seamless flow of postures) with the wisdom learned on a youthful surf safari, and dubbed it Power Vinyasa.

Today, with millions of adherents spending as much as $1,500 a year on classes and merchandise, American yoga is a $22.5 billion enterprise. And, not surprisingly, huge numbers of strivers would like to join the ranks of the well-heeled stars.

In this crowded field, the Iron Yogi ranks as an accomplished player who hasn’t—yet—achieved the headliner status he envisions. To get there, he’ll have to distinguish himself from the 300-plus new teachers popping up every month. Which means Turbo Vinyasa will have to stand out from the 74 class styles—ranging from ashtanga (created by a guru in a cave in Tibet) to Soul Sweat Asana (emphasizing “fun and freedom in the body”)—that are self-registered with Yoga Alliance, a five-year-old national organization charged with the difficult task of keeping tabs on yoga’s “diversity and integrity.”

Asked to size up the Iron Yogi’s chances, Power Vinyasa honcho Baptiste says they’re pretty good. “There is a market and a place for high-intensity, extreme yoga,” Baptiste says. “The type A’s would definitely love it.”

Birch, the Power Yoga maven, argues that the guru market is facing a glut. “Back in 1980, mention that you do yoga and people would have you locked up,” she notes. “Now everyone’s doing teacher training. Pretty soon it’s going to be all teachers and no students!”

She’s only half joking. In America today, anyone can be a yogi.

SEAMAN’S LIFE STORY proves as much. Born in 1958, son of a traveling sporting-goods salesman and a stay-at-home mom, he struggled through high school and dropped out of the University of Colorado after one semester. By the late 1970s, his greatest physical feat was polishing off an extra-large pizza and a half-gallon of Mount Gay Rum. He fed a 50-pound gut, smoked two and a half packs a day, and made ends meet by selling shoes at Gart Brothers Sports Castle, in Denver, a job his father found him.

“His butt was so big that if you ever needed shade, you knew where to stand,” says Bret Glass, his roommate at the time and a friend to this day. “Seriously, he was a Taco Bell–eating pig.”

Glass, a safety on the Colorado football team, got sick of Seamans’s sloth and, one day in 1980, dragged him to the gym. “I remember it like it was yesterday,” Seamans says. His legs collapsed after a couple of squats. His shoulders gave out after seven reps on the military press—with an unweighted bar. The next morning he woke up so sore that he could barely turn off his alarm clock.

But he was hooked by the healthy masochism. He called in sick to work. Quit the Marlboros cold turkey. And went straight back to the gym to lift weights. Four months later and 40 pounds lighter, he snagged a job managing the Atlantis 2000 health club in Boulder.

For the next 18 years, Seamans moved back and forth between Colorado and California, competing in bodybuilding competitions; buying, operating, and selling gyms; and working as a personal trainer and health educator. In 1997, both his personal and professional lives took off. He married Marisol Terán, a Venezuelan kickboxer and cyclist. He began training Chopra and Robbins and taught a 2,000-client-per-month Spinning class, the largest in the world, at the Personalized Workout club in La Jolla, California.

The bottom fell out in 2000, when Seamans lost $250,000 during a contract dispute with the other investors behind Personalized Workout, in which he says he was supposed to have part ownership. That same year, he and his wife were divorced. Dejected, he took a job marketing a line of work gloves and tried to get his life in order. Just a few months later, he happened to drop in on a yoga class at a gym called Cardiffit, in Cardiff-by-the-Sea, California.

“At savasana, the relaxation pose, I started seeing colors at the point between my eyebrows—purples, greens, golds,” he remembers. “When the instructor, this little Brazilian girl, told me those were the chakra colors, I knew I would be a yoga instructor.”

Not long after, he flew to Nosara Yoga Institute, in Costa Rica, for a one-month teacher-training course and stayed, he says, nearly 11 months, practicing six hours a day. Soon, Seamans began braiding his spiritual and jockish smarts into a yoga of his own, one that was strenuous enough to offer the benefits he found in both yoga and weight lifting. The goal was to create as many “big bang” postures as possible, involving what he calls the “holy trinity” of athletic performance: stability, flexibility, and strength.

When he’d strung together enough poses for an hour-and-a-half course, he called it Turbo Vinyasa. In 2002 he started teaching at Flatiron. The Iron Yogi was born.

These days, Seamans says he earns more than $100,000 a year, primarily from $85-per-hour private personal-training sessions, but he still chooses to live in the sparsely decorated caretaker’s quarters of a multi-million-dollar estate ten minutes outside of Boulder. (A family friend and personal-training client offers it to him rent-free in exchange for his looking after the property.) The apartment, about 350 square feet, is attached to a deteriorating barn and is humble indeed: mint-colored shag carpeting, sloping ceiling, thin wood paneling. Two beanbag chairs face the medium-size TV in the tiny living room.

Why does he eschew worldly things? “I’m a simple guy,” he says. “I have everything that’s important to me.”

AFTER COMING TO CLASS off and on twice a week for three months, Turbo Vinyasa has issued me mostly physical dividends. The folds in my belly have turned into hints of abdominal muscles, and for the first time in years I’ve finished a season of telemark skiing without tweaking a knee. So I’m keeping the faith and holding out for the magic, if only because the classes are never boring, and neither are the students. They’re down-to-earth, fanatical athletes, a combo you don’t find every day. And they crave Turbo Vinyasa like mad carbs.

“It’s the only yoga I’ve ever stuck with,” says 32-year-old Sara Nelson, a competitive triathlete. “When I miss a week, I definitely feel it in my back. I’m hunched over like a turtle.”

“I don’t come inside for much, but I joined Flatiron in the spring just for this yoga class,” says 42-year-old Daniel Krahe, a Class IV kayaker and ultra– distance runner. “Balancewise, it’s phenomenal. I walk out of here better than I walked in—literally.”

A couple weeks later, I hit the pincha mayurasana forearm stand. Just as it did for the former cheerleader striking the bird-of-paradise pose, it happens totally unexpectedly. One moment I’m an exhausted mortal thinking about frothy mugs of ice-cold beer; the next I’m an exhausted mortal who’s fully upside down without harness, block, or tackle and using muscles that I didn’t even know I had. As the Iron Yogi begins leading the closing 15-minute visualization, I lie back on my mat, feeling wholly spent and sure that something divine is beckoning in the distance.

“Maintaining focus on your third eye, picture or imagine the number 10,” Seamans intones.

I hear kapwack-kapwack from the racquetball court next door, but I pull my concentration back to the numerals, which I envision as a Grecian column and a bike tire.

“Take a slow, deep inhale,” he instructs. “As you exhale, allow your body to soften … one … level … down … “

Each of my limbs melts into the floor, and dissolves even further as he counts down to 9, then 8, then 7. I’m leaving the outer world. Somewhere around 6, I’m gone. Everything goes black.

I’ve fallen asleep, exhibiting all the heightened spirituality of a two-by-four.