Podcast: Listen to Stephanie Pearson’s feature story

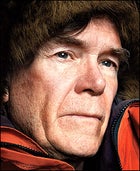

Will Steger

Will Steger at his home near Ely, Minnesota, January 2007

Will Steger at his home near Ely, Minnesota, January 2007Will Steger

I'm a dreamer and a doer: Steger dogsledding on the Arctic Ocean

I'm a dreamer and a doer: Steger dogsledding on the Arctic OceanWILL STEGER IS LATE for an appointment, and the world’s greatest living polar explorer is losing some of his cool in the purgatory of Southern California traffic: “We’re lost, dammit!”

Steering his rented Dodge Stratus into a leafy side street in Santa Monica, Steger stops for a route check. His co-pilot, Elizabeth Andre, a 29-year-old former Miss Teenage America turned Outward Boundinstructor, is trying to decipher a hand-drawn map, while Theo Ikummaq, a 52-year-old Inuit hunter and guide from the Canadian Arctic, sits quietly in the backseat, paying no heed whatsoever to his new Swiss Army watch as the hands creep toward two o’clock.

Theo is more interested in the hot-pink bougainvillea outside the car window. Where he lives, it’s mostly dark this time of year, and he’s loving the subtropical sunshine and flora. Just a few minutes ago, as we sped down Highway 1 from Malibu, he pointed to a tangled jungle of palm fronds and joked, “These plants aren’t plastic?”

Steger and Andre get reoriented and before long we’re inside the Marmalade Cafe for a sit-down with Laurie David, a co-producer of An Inconvenient Truth and wife of Seinfeld co-creator Larry David, and Diane Isaacs, a co-producer of Killing Pablo, a forthcoming film about drug lord Pablo Escobar. Isaacs takes the beverage order while David, smartly dressed in a gray velour jacket, gets down to business.

“You’re the first Inuit I’ve ever met!” she tells Theo. With his close-cropped black hair, khaki pants, and polo shirt, Theo could pass for an Angeleno. The only giveaway is his baggy white anorak.

“It’s an honor to meet you, Will,” says David, turning to Steger. “How has your work been going?”

In most photographs, Steger is the ├╝ber-snowman, with his fur-lined hood and mukluks, but in real life he’s less intimidating. Wearing Levis and a T-shirt, the 62-year-old is a fit and sinewy five foot nine. He has wavy brown hair that says ex-hippie; his gray-blue eyes flicker between expressions of delighted animation and steely non-emotion.

Steger tells David he’s in L.A. to generate buzz about his upcoming Global Warming 101 expedition, a four-month, 1,200-mile journey across Baffin Island, the 195,298-square-mile chunk of Canada’s Nunavut Territory that sits between Greenland and Hudson Bay. The trip, which represents the official end of a decade-long semi-retirement for Steger, was slated to begin February 18, with a crew composed of Steger, Andre, Theo, four other American and Inuit crew members, and four sled teams. The plan is to village-hop, shooting interviews with Inuit elders to document how global warming is changing their lives. Steger and company will also spread the word, via satellite, on , a clearinghouse for global-warming news and information that includes a special educational section for schoolkids.

Isaacs, a world-class triathlete, will join the team at three points along the way. En route, she’ll edit the footage into a five-minute teaser, which she’s already started promoting to potential partners like Tree Media, the company producing Leonardo DiCaprio’s environmental documentary 11th Hour. The $700,000 project is being funded by private donations and four corporate sponsors, but the ultimate goal is to interest studio bigwigs in producing a film that, according to Isaacs, “won’t be your typical National Geographic documentary.” She’s thinking more like An Inconvenient Truth meets YouTube┬Śan entertaining, marketable, wide-release teaching tool set against the rich backdrop of polar life.

But first things first: Steger is in town to meet people, so Isaacs has turned his visit into a five-day endurance event. This morning Steger gave a PowerPoint presentation to the student body at an upscale Episcopalian school in Pacific Palisades. (The takeaway: “Global warming is all you’re going to hear about for the rest of your lives.” ) Tomorrow, he’ll have lunch with Howard Ruby, a real estate magnate and professional photographer who’ll join the expedition in March.

Now that David has the gist, she fires a question at Theo: “What are you seeing up in the Arctic?”

“In the last five years, new animals┬Śrobins, finches┬Śhave come in, and we don’t even have names for them,” Theo says. “And older folks aren’t comfortable to go off the land anymore…. We’ve lost about one-third of the summer sea ice.”

“Polar bears are starving to death,” Steger interjects. He fires up his laptop and clicks to a photo of an emaciated furry mass, lying dead on the tundra. “This polar bear was 300 pounds when it died,” he says. “It should have been 1,700 pounds.”

Bears starve, Steger explains, because melting sea ice can cut off their access to the ocean’s rich food supply.

David, who’d been scribbling notes, literally starts waving her arms. “I want to put this image up on my Web site!” she says. “Let’s get this image out there! It’s shocking. Shocking!“

Business cards are exchanged, hands clasped. “I’m at a loss for words,” says David. “That never happens.” Everyone stands around in awkward silence until she says, “This is the beginning of a beautiful partnership, I’m sure.”

IF IT WEREN’T FOR GLOBAL WARMING, Steger, a self-described “closet introvert,” might still be living “a beautiful, simple life” at the Homestead, his 240-acre, 100 percent solar-, wind-, and propane-powered compound near Ely, Minnesota.

But that life is on hold, as is Steger’s once-firm plan to retire from expeditioning. I visited him at the Homestead last November, prior to the L.A. trip. On a suspiciously balmy Minnesota afternoon, during a tour of a half-dozen Homestead buildings where Steger designs and builds equipment for his many adventures, he told me that, after three decades of traveling over polar ice, he’s found his true calling: to make the world confront the reality of climate change.

The reality, as Steger sees it, is clear. The heat is on, thanks largely to the rapid release of carbon dioxide brought on by mankind’s burning of fossil fuels. Today, CO2 levels are the highest they’ve been in at least 650,000 years, with effects that are most obvious in the polar regions. Two major ice shelves, the Arctic’s Ward Hunt and Antarctica’s Larsen, have broken up in the past 20 years, while Arctic sea ice has lost a third of its thickness and more than a quarter of its extent.

Steger, who’s seen the changes unfold firsthand, has been infatuated with climatology, meteorology, and biology since he was eight. To him, the situation makes it impossible not to do something.

“Once you see what’s happening as a moral issue, the mass extinction and other implications of what we’ve done and what’s going to happen,” Steger says, “you lose a certain purity of peace that forces you into action.”

This from a man whose mind and body are in perpetual motion. At 15, Will and his older brother, Tom, launched a powerboat journey from Minneapolis down┬Śand back up┬Śthe Mississippi River, occasionally landing in jail and getting sprung only after their parents assured the police that they hadn’t stolen the boat. When Steger was 17, he and a buddy hitchhiked to Juneau, Alaska, where they paddled across blank, unmapped territory in the Yukon and Alaska.

Between adventures, Steger worked odd jobs to pay his way through Catholic high school, college, and graduate school. In 1970, he hitched to Colorado, where he was hired on the spot as an Outward Bound instructor. Two years later he moved to California, where he spent time at a Zen monastery, followed by weeks of trekking and fasting in the Sierras. In 1974 he returned to Minnesota, where he leased a team of sled dogs and started an outdoor-education school at his property near Ely.

“Everyone thought I was nuts,” says Steger, referring to the locals, a stoic Slavic bunch who earned a hard living out of timber and mining. “I didn’t know anything about sled dogs.”

He learned, and in 1982 he launched an 18-month, 7,200-mile dogsled expedition in the Canadian Arctic and Alaska, which inspired him to try another polar trek┬Śall the way to the North Pole. The aim was to do it the hard way, taking everything his eight-person team needed and nothing more.

“The North Pole was do or die,” Steger says. “I was not coming back unless I made it.” In 1986, Steger’s team became the first to dogsled to the top of the world without resupply.

“Will is an absolute genius at expedition logistics,” says Paul Schurke, the co-leader of that famous trip. “We left the north shore of Canada with 7,000 pounds of supplies, which Will tracked meticulously. We arrived at the Pole with eight pounds left.”

Steger parlayed his skill into other firsts: In 1988, he completed a 1,600-mile south-north traverse of Greenland, the longest unsupported dogsled expedition in history. In 1989┬ľ90, he led the International Trans-Antarctica Expedition, a 3,741-mile dogsled traverse of Antarctica, a massive $2.5 million undertaking.

“The first North Pole trip was like a sporting event,” Steger says. “But the purpose of Antarctica was to make the continent famous, so that world leaders would protect it from mineral exploration.”

For more than seven months, Steger and five teammates battled windchills of minus 150 degrees and mind-numbing whiteouts. After they finally succeeded, the exuberant multinational team traveled the globe, lobbying leaders to forbid mineral extraction in Antarctica. In 1991, the Protocol to the Antarctic Treaty was adopted, banning mineral and oil exploration on the continent for another 50 years.

After a fourth major expedition┬Śa successful traverse from Russia to EllesmereIsland in 1995┬ŚSteger’s luck ran out. In 1997, just seven days into a solo attempt to haul and paddle from the North Pole to Ellesmere Island, he aborted.

“I was dropped off at the Pole by a Russian icebreaker and got into horrible conditions,” Steger told me as he stoked a fire inside his compact bachelor cabin, which is packed with books on architecture and exploration. “I made one final try and, for some reason, I just said, No m├ís. I had to organize a rescue.”

And that was it.

“I left expeditioning,” Steger said. “The demands of marketing and the media were too complicated. I was so stressed that I came back here. It was quite a relief.”

A DECADE LATER, Steger is hanging out in a tony Los Angeles neighborhood┬Śnot a place you’d expect to find him. Just now he’s sitting lotus style on the floor of former supermodel Cheryl Tiegs’s Balinese-style living room, listening to Frank Sinatra sing Christmas carols and watching Tiegs, Theo, and a few other guests trim the tree while he shoots the breeze with actor Ed Begley Jr.

Begley is one of Hollywood’s original greenies. He lives in a solar house, drives an electric car, and has a new television show, Living with Ed, that debuted on the Home & Garden network in January.

“Living with Ed is basically about what it’s like to live with an environmental zealot,” Begley tells Steger. “It’s like a 21st-century Green Acres.”

“The show is great,” says Rachelle Carson, Begley’s co-star and wife. “If I can go green, anyone can.”

“Even Danny DeVito solarized his house,” Begley adds. “Everyone wants to take action.”

Steger nods, but I have to wonder if he’s ever heard of Green Acres or Danny DeVito. Theo, on the other hand, seems ready to give the environment a rest. Earlier, he discovered a new gadget in Tiegs’s kitchen. (“Is this one of those iPods that everybody’s talking about?”) Now he’s engrossed in his first-ever tree trimming, which is one tradition Catholic missionaries didn’t force on the Inuit, given that there are no evergreens where Theo grew up.

This is Steger’s third trip to L.A. in five months, and he’s finding the SoCal lifestyle agreeable. “It’s sort of like a vacation,” he told me on the ride over. “I never paid attention to Hollywood. In fact, a lot of times I don’t know who I’m meeting. But I like the attitude, and it’s an engine for change.

“Plus,” he adds, “it’s fun.”

Steger has pressed flesh before┬Śin the eighties and nineties, he spent a lot of time in Washington, D.C., working with Al Gore and the Wilderness Society on issues like Arctic preservation┬Śbut Hollywood is a different world. The fact that he’s here, eating steak with the stars, involves a curious convergence of events, starting in 2002 with the breakup of the Larsen Ice Shelf, which he’d traversed in 1989. Such signs of climate change dovetailed with his increasing irritation with the Bush administration, which, in his view, showed little interest in taking a serious look at global warming.

“The president was doing nothing about the environment,” says Steger. “It was making me angry. I started to feel negative, and I can’t live with negativity.”

Finally, in 2003, Steger had a fateful lunch in St. Paul with fellow Minnesotan and explorer Dan Buettner, who invited him on an expedition to retrace the frankincense route through the Middle East. That never happened, but the conversation inspired Steger┬Śwho’d been cooling his heels for years at the Homestead, reading, writing, woodworking, and mounting small-scale expeditions┬Śto get back in the game. In January 2006, he created the Will Steger Foundation, an environmental nonprofit based in Minneapolis.

“Will eats, breathes, and sleeps global warming,” says Buettner. “He’s hardwired to thrive with a sense of purpose. His resurgence has been like Lazarus rising from the grave.”

Buettner had a few contacts in Hollywood, starting with his longtime girlfriend, Cheryl Tiegs. Tiegs had met Steger years before and was excited to introduce him to friends.

“In Hollywood, we’re just talking about global warming and thinking about it and wondering about it,” Tiegs tells me. “We’re not particularly living it. Will is our conduit to the people who are really going to suffer. What he’s doing is unique.”

The fun at Casa Tiegs winds down before midnight, at which point Steger slips outside to a chaise lounge at the edge of the swimming pool. Tiegs has given Steger the run of her house, but, true to form, he prefers sleeping under the stars.

TWO NIGHTS later, Steger is back on the party circuit. This time it’s a mellow gathering at Diane Isaacs’s art-filled home in Brentwood. Looking refreshed after a three-hour hike in the Santa Monica Mountains, Steger mingles with early arrivals while Diane’s husband, Greg, an athletic trainer from South Africa, shows a few digitalphotos of Lance Armstrong training for the New York City Marathon. Greg was his coach.

Isaacs has assembled an impressive group. On hand for margaritas and homemade paella are Lew Coleman, president of DreamWorks Animation; Lloyd Phillips, a producer from Sony; Beau St. Clair, Pierce Brosnan’s production partner; Richard Bangs, an explorer and entrepreneur; and Bangs’s girlfriend, Laura Hubber, a reporter for the BBC.

Just before everyone sits down to eat, Peter Guber, the producer of The Color Purple, Gorillas in the Mist, and other blockbusters, rolls in with his wife, Tara, a redhaired fireball who’s heavily into yoga and the environment. She’s toting a copy of Contact: The Yoga of Relationships, a book she co-wrote. After hearing about Steger’s exploits from her friend Isaacs, she insisted that her husband meet him.

Peter Guber skips the buffet and sits next to Theo and Steger, who listen silently as Bangs quizzes Guber about movies. “What do you think is the most impactful film you’ve ever made?” he says.

“Gorillas in the Mist made a huge impact,” Guber says, shaking the ice in an empty Starbucks cup. “Movies are an emotional issue, just like the environment. But in the end, it all comes down to the pocketbook. It’s the same with global warming┬Śit’s market-driven.”

After dinner, guests migrate to the living room for Steger’s slide show, while Guber self-mockingly vents about the type of Hollywood environmentalist who owns both a hybrid and an Aston Martin┬Ślike he does. “I had a friend who bought a car that ran on French-fry oil,” he jokes, “but it always made him hungry!”

Steger, who kept mum during dinner, starts clicking through slides of receding polar ice, mixed with charts and graphs. After 20 minutes, he turns the floor over to Theo, who tells it like it is.

“I was born in an igloo. We had no electricity. We lived nomadically and traveled by dogsled to visit relatives,” he says. “My culture has been the same for 8,000 years. But it’s changed drastically in the last 30 years. Who knows what’ll happen in the next five?”

Soon, the lights come on and the group sits in silence. Bangs tries to lighten the mood. “I have a dumb question,” he says to Theo. “Why can’t we just put polar bears in Antarctica and penguins in the Arctic?”

“I don’t think they’d adapt very well,” Theo replies.

ON THE EVE of New Year’s Eve, expedition prep is in full swing at the Homestead. Isaacs has flown in, and most of the team (minus Theo, who’s getting remarried in two weeks) is getting down to brass tacks as the launch date approaches.

Since the Hollywood schmoozefest, climate change has remained big news┬Śthanks in part to the release of the UN’s latest report on the subject, a six-year effort that offers a gloomy assessment of planetary health. Laurie David and Steger have started cross-pollinating with shared Web links; Isaacs is negotiating to use an unreleased Tupac song in the teaser’s soundtrack; and Lloyd Phillips, the Sony producer, has passed word about Baffin Island to a friend who passed it on to billionaire Richard Branson. Branson got excited, and he and his 21-year-old son, Sam, are joining the trip for the last two-week leg.

“We haven’t even tried to go after celebs yet,” says Isaacs. But the list keeps growing anyway: Mountaineer Ed Viesturs has committed to a two-week stint; Cheryl Tiegs will fly up for a week with Howard Ruby; even Pierce Brosnan might make an appearance.

“We’re definitely on good footing in L.A.,” Steger tells me later. “But I was really there to make long-term relationships.”

In 2008, Steger will kayak the open water of the Weddell Sea. In 2009 he and the team will head to Greenland for another overland dogsled trek. “Western Antarctica and Greenland will determine the fate of our civilization,” Steger says. “Greenland holds 12 percent of the world’s freshwater, and if its ice cap becomes unstable, it could be catastrophic to our society.”

Steger and Isaacs hope to parlay the next two expeditions into movie deals, too. But Steger says the movies don’t mean much to him by themselves┬Śthey’re strictly a medium for getting the word out faster. He’s the first to admit he’s in a hurry. He can’t muscle an 800-pound dogsled forever.

Which may be why he’s working so hard on one of his final acts: completing the construction of an ambitious, soaring structure he calls the Castle.

Taking the money he earned by licensing his name to Target┬Śwhich in the late eighties created a Will Steger line of tents, packs, and sleeping bags┬ŚSteger and a few locals have been slowly erecting a massive stone, glass, andrecycled-timber building. The six-story Castle, which sits on a hill and dwarfs the cluster of cabins at its base, has decks shooting off in every direction and roof angles that make it look like it’s sailing across the landscape.

When it’s finally finished, around 2010, the Castle will serve as the think tank for the Will Steger Foundation, drawing small groups of activists, politicians, and industry leaders from around the world to cook up new ideas about education, the environment, or whatever profound matter needs addressing.

“Thirty years ago, I realized that, to make an impact, you have to bring together decision makers,” Steger tells me as we watch the sun sparkle off Picketts Lake from a Castle deck. “The setting will provide inspiration and vision. Seventy years from now, this will all be covered by virgin forest,” he says, pointing to the motley buildings below.

But the Castle will endure, Steger points out. Visionary pragmatist that he is, he hopes the Will Steger Foundation will endure as well. “I’m sort of like a dreamer and a doer,” he says. “A real dream is something you have to do.”