TO LOOK AT ANDY RODDICK between sets one and two of his first match at the Sony Ericsson Open, in Miami, this past March was to see a man apparently deflated. He sat slumped, his face pointed straight down as if searching for solace in the purple hard court beneath his sneakers. There was no movement save for the occasional twitch of the water bottle dangling from his fingers. He had just lost his first set since bowing out in the second round at his previous tournament, the Pacific Life Open, in Indian Wells, California, an undeniably disappointing result in a season that had seemed, for the most part, overstuffed with promise.

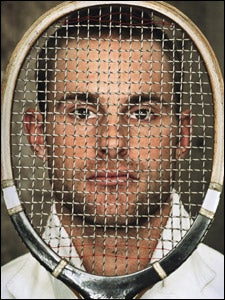

Andy Roddick

Andy Roddick

Andy RoddickAndy Roddick

Roddick in New York, April 2008.

Roddick in New York, April 2008.Andy Roddick

I have to have windows every couple of months where I can put my body back together.-Andy Roddick

I have to have windows every couple of months where I can put my body back together.-Andy RoddickIt was the sort of match that, in previous years, Roddick would probably have lost. His talent is unmistakable (hence the 25 singles titles, including the 2003 U.S. Open) and his physical condition is almost peerless (he hired his first full-time traveling trainer in 2001 and has continued to upgrade a massive off-season routine see “I’d Rather Be Playing Tennis”), but the American’s mental strength has not always been so certain. While Switzerland’s Roger Federer is implacable, Roddick is the opposite: an effusive, exuberant, extemporaneous bundle of emotion, capable of winning or losing a match on the whim of a moment. As his mood goes, so goes the match. At least historically.

There in Miami, Roddick, ranked sixth in the world, had just fumbled the first set against an all-but-unknown opponent Serbia’s 22-year-old Viktor Troicki, No. 103 and was struggling with the accuracy of his cannon-like serve, trudging around the court in frustration. For all I had heard about a new Roddick still riding the momentum of December’s Davis Cup championship, an energized player who had won two tournaments so far in 2008 and defeated both No. 3 Novak Djokovic and No. 2 Rafael Nadal in the process, I couldn’t help but think I had flown to Miami to witness a familiar sight: Andy Roddick imploding.

The early moments of set two weren’t much better. There was barking, cursing, even a chucked racket. But Roddick fought, improving his service game, and then, up 3-2 and given an opening to break Troicki’s serve, he pounced on a lazy forehand and cracked a sizzling crosscourt winner for the game. He howled, pumped his fist, and turned to the crowd, which erupted. In the stadium, the momentum shift was visceral.

In the third set, the two players traded holds until Roddick, up 5-4, struck one of the most memorable shots of his career, a no-look backhand flick on a ball that had seemed impossible to reach. Not only did he reach it; he hit it past Troicki into a tiny sliver of open court. The trajectory seemed to defy science. You wondered if Ang Lee was directing. Roddick later called it a “freak-show trick shot.” The next few points hardly mattered. Troicki was finished.

Upon winning, Roddick thrust his arms to the sky. It was a big reaction for a small match and, as the tennis world would find out a few days later, a sign of more to come.

This year, Andy Roddick will not go quietly.

For a video review of new tennis gear in ���ϳԹ���’s Go, .

OF COURSE, ONE could take an alternative view: that struggling against a middling player was just a harbinger of the Next Great American’s ongoing fade into mediocrity.

It’s a reasonable sentiment. After bursting onto the global tennis scene with a nuclear serve (world-record speed: 155 miles per hour), a howitzer of a forehand, and a bombastic personality that charmed beat writers and agitated the competition, Roddick rocketed to No. 1 in the world rankings in 2003 then crashed into a wee bit of a brick wall in the form of Roger Federer, a.k.a. the Greatest Player in the History of the Sport. Over the ensuing four years, Roddick lost to Federer 15 of 16 times, including twice in the Wimbledon final. In the past several years, he’s also fallen behind Nadal, the 22-year-old Spanish capri-pants enthusiast who dominates the French Open every year; and Djokovic, the lanky 21-year-old Serb who won the Australian Open in January. If you listened to critics and there were many Roddick had drifted into the second tier of top pros. He was an athletic player who could make a run at any given tournament but was destined to languish somewhere in the lower half of the top ten.

It seems funny to imagine that someday this trivia question might stump people: Who was the last player to hold the No. 1 ranking before Roger Federer’s epic reign? The answer: Andy Roddick, then 21, now 25 and, despite rumors of his demise, very much still a force on the ATP Tour. Barring injury, he’s got at least five years of elite tennis left in his body. While he’s unlikely to take the throne back from Federer, Roddick clearly believes he’s going to win more Grand Slam events. And he’s probably right.

Here’s what he says he was really thinking between those sets in Miami, when I was ready to stick a fork in him: “I lost a set 7-5. The guy played great. I served 35 percent first serves. So I was just thinking over stats and telling myself, You know what, this could turn quick, and when it does, it could go fast.”

After dispatching his next two opponents, Czech Ivo Minar and Frenchman Julien Benneteau, to reach the quarterfinals, something momentous happened: Andy Roddick slew the dragon. He beat Roger Federer. And as he did in the match against Troicki, Roddick took some punches. He won the first set, then lost the second, and Federer entered the third in one of his bizarre zombie zones, in which he reels off points by the dozens, hitting shots that mystify and frustrate opponents.

Only this time Roddick hung in. “When he was hitting the shots, I would turn around and walk back [to the service line] and wouldn’t do anything,” he told me later. “I would just go to the next point. As simple as that sounds, that’s literally what I was thinking. I got through a game with three or four break points and all of a sudden he actually froze. I think me actually staying the course gave him the opportunity to make mistakes.”

When reporters swarmed the interview room to ask a very happy Roddick what had pleased him most about the match, the first thing he said was “I thought I stood the course mentally pretty well.” Pressed to assess the significance of this quarterfinal match, Roddick said, “It’s probably what’s been missing the last two, three years.”

Talk about an understatement.

Taking the long view, the win over Federer in Miami was a sort of tangible proof of something bigger: a slow rebirth that dates back to the Davis Cup title last December, the first for the U.S. since 1995. Entering 2008, Roddick won in San Jose, then won again in Dubai, beating both Nadal and Djokovic. Despite the stumble at the Pacific Life Open, he arrived in Miami feeling as sharp as he had in years. One reason became clear during the tournament, when news leaked that he’d gotten engaged to his girlfriend, the gorgeous blond Sports Illustrated swimsuit model Brooklyn Decker, 21, thus ending his tabloid-covered bachelor years, during which he’d dated, most prominently, Mandy Moore and (allegedly) Maria Sharapova. “I think being happy and content off the court is only going to help in my mind,” he told reporters after the Federer match. Another boost came in the form of Federer suddenly appearing, if not vulnerable, then at least less invincible. He’d already stumbled in the early part of the season, losing to Djokovic and Scotsman Andy Murray, and in February he was diagnosed with mononucleosis. In Miami, Roddick would go on to lose in the semifinals to 27-year-old Nikolay Davydenko, but the Russian was by all accounts playing the best tennis of his career. Two days later, Davydenko absolutely smoked Nadal in the final.

“Roddick has matured a lot,” says Davis Cup captain Patrick McEnroe. “He still has the same drive and intensity he just seems more balanced. And that helps him in big matches. I think his chances [in Grand Slam events] are as good as they’ve been in years.

So Roddick heads into the meat of this season to Wimbledon, the hard courts, and his home slam, the U.S. Open with a new fiancée, a clear mind, and something even more significant: a giant Swiss monkey off his back.

“If I’m serving for a set next time, I’m not going to be thinking, Is this the time? God, please let this be the time,” Roddick told me two weeks after his victory, the relief in his voice still palpable. “I think it’ll be a little bit more straightforward.”

Meaning you’ve had those thoughts before?

“I’d hope you’d call bullshit on me if I said, after losing 11 times in a row, I’m serving for match and that thought didn’t creep into my head. That’s why I said it was huge mentally for me in Miami.”

THAT RODDICK HAS been entrenched in tennis’s top ten for most of the past six years (at press time, he was still ranked sixth) without suffering serious injury is pretty solid proof of his commitment to off-court training. He has always been ahead of tennis’s fitness curve. Though he’s gone through a string of coaches, including, from 2006 until early this year, Jimmy Connors in the role of consultant (Roddick insists they parted amicably after Connors decided he didn’t want to endure the travel obligations of the pro tour), he now seems to have settled into a groove with a team composed of his coach/brother, John, 32, and athletic trainer Doug Spreen, 38, hired away from the ATP in 2003.

On a remote practice court in Miami, the day before Roddick would face Federer, I watched Spreen dilute a sports drink, cutting it in half with water so that it “absorbs quicker.” Roddick, Spreen said, has two things working against him when it comes to fitness. One is his size: At six-two and 195 pounds, he’s taller and thicker than most top pros. The other is a higher-than-normal sweat rate. (“I’m disgusting,” Roddick said, pausing to set up his own joke, “which was a real problem with my personal life for a long time.”) Because he’s losing more fluids than his opponent, Roddick has to make a real effort to stay hydrated. “When I’m training I go through six, seven, eight liters of water just replacing what I need to. It’s definitely more effort.”

Out on the court, Roddick was blasting balls. “The forehand’s coming off good today,” he said to his brother. Roddick’s forehand, like his serve, is among the best on the tour and requires both strength and resilience more every year as players get stronger and faster. “If you’re gonna hit 150 balls that much harder in a match, it takes that much more energy,” Spreen explained. “And two guys hitting the ball harder at each other means that they’ve got to move that much quicker to get the ball. They have to be ready to play a more explosive game.”

To this end, in 2005 Spreen enlisted the help of Lance Hooton, the Austin-based owner of Hooton Sports Performance Training, an outfit that focuses primarily on what Hooton calls “power-speed athletes.” Hooton says Roddick was in excellent shape and, more important, eager. “I can go down a list of phenomenally gifted athletes who are not willing to learn,” Hooton says. “Andy is the opposite of that. His work ethic is incredible. I only know a handful of tennis players who even come close to what he does off the court.”

Still, some of Roddick’s athletic skills were lacking, and his training had been focused on endurance. Hooton set about creating a regimen to build power and speed, particularly important for the world’s hardest-serving player, whom Hooton calls “the Nolan Ryan of tennis.” Hooton stepped up Roddick’s weight training, implemented body-weight-resistance programs and plyometrics, and added sprint intervals. The intervals serve to increase his quickness and, as Spreen reminds me at another point, his recovery.

“If you’re playing a service game, you go out and you play a 45-second point and you’ve got 25 seconds before you’re serving again,” Spreen says. “That’s where you get into the interval training: sprint, recover, sprint, recover. You train the body to be stressed and to recover quickly from that stress.”

Roddick says tennis’s ephemeral off-season (more or less a month with Christmas sandwiched in the middle) is when he gets the opportunity to “build, build, build.” Once tournaments get rolling, he plays so often that his fitness program is highly erratic. Hooton gives the team a number of options for light-, medium-, and high-intensity days and also plans for days on which Roddick should only jog and stretch. “You have to give yourself time to give your body a break,” Roddick says. “I’ve become real particular about that. I have to have windows every couple of months where I can put my body back together.” He also makes sure to have some non-tennis playtime, tearing around Texas’s Lake Austin (where he’s owned a home since 2003) on his speedboat and trail-running in a nearby wilderness preserve.

“People make fitness out to be this whole specific thing,” he says. “But, basically, if you’re willing to put in the hours and go through the grind, you’re going to be OK.”

WHICH LEAVES only one thing: What of the supposedly fragile mind? “You know, you’re out there for two or three hours by yourself and you’ve got to figure it out on your own,” says Spreen. Tennis is probably sports’ most individual game. Mid-match coaching is illegal. The pro player is utterly alone on that metaphorical island, left to work himself into or out of crises.

“It’s something we’ve talked about,” says his brother John, who was once ranked sixth in the world as a junior. “When I played I was similar, so I can relate. You want to keep your composure so you [can] give yourself an opportunity to win the match if you’re not playing your best tennis. And for the most part he does a good job of that. Sometimes he’ll let an umpire get on him or something, and it’ll upset him.”

But John points out that, at least in his brother’s case, there’s an upside to the volatility. Roddick is a fiery athlete who feeds on emotion. He’s never going to be Mr. Cool on the court, and it wouldn’t make sense to ask him to try. “If Andy just bottled everything up, he wouldn’t be able to play very well,” John says. “He’s gotta let that out. To be honest, him getting a little upset on the court is not something we tend to focus on.”

In fact, they let Roddick work things out all by himself. The team never hired a sports psychologist or attempted to mix any specific mental training into his routine.

“I think it’s just experience,” says Roddick. “You’ve done it before” lost your shit, he means “and maybe you can handle it a little more. But I don’t think I’m ever going to be one of these guys who can just mute it.”

He tells me this on a beautiful April day in New York City, where he’s come to help his fiancée move them into a new Manhattan pied-à-terre. He’s fresh off a convincing Davis Cup quarterfinal win over France and has been instructed by Spreen and John to leave the racket in its holster for a few days. But Roddick is set to meet with Patrick McEnroe in the morning, which he says has him “jonesing” to hit some balls. “It’ll be hard not to play tomorrow,” he says.

Roddick’s publicist and sister-in-law, Ginger, who’s been escorting him to interviews, gives him a look. “Do something else,” she pleads.

Roddick looks right back: “I’m not good at anything else.”

WARM-UP: 100 meters each skips, side shuffles, backpedals, and jog. > Static stretches, held 20 30 seconds. > 20 meters each down-and-back A-skips, butt kicks, backward skips, backward runs, lateral walks, crossover walks, lunge walks, power skips, and carioca. > 10 reps each side leg swings, scissors, eagles, mule kicks, and leg whips.

SPEED: 6 8 reps each: 20-, 30-, and 40-meter sprints. Walk back between reps, rest 3 minutes between sets. > Medicine-ball throws (8 10 pounds): 6 reps each overhead back, forward between legs, hip hammer throw (right and left), and squat chest. > Holding a seven-foot pole, 10 reps each of 16 different torso-mobility exercises (found in an old Finnish javelin textbook). > 4 rounds skips and jumps over 30-inch hurdles. For one, alternately jump a 30-inch hurdle, then laterally duck under a 36-inch hurdle. > Easy 400-meter jog on grass, ideally barefoot.

STRENGTH: > Holding dumbbells (25 percent of body weight total), 4 sets of 8 step-ups to an 18-inch box, alternating with 4 sets of 5 pull-ups. > Holding a 25-pound plate 6 inches from chest, 3 sets of 15 reps of walking lunges to Russian twists (lunge to one side, then twist torso to same), alternating with 3 sets of “wipers” (with plate at arm’s length, rotate and arc arms from one hip to eye level to other hip.

COOLDOWN: 7 minutes of easy stationary biking; protein-and-carbohydrate-rich smoothie; then 10 minutes in an ice bath.