WINDS WERE POURING out of northwestern Alaska’s Brooks Range at 45 knots, hurling our helicopter in oscillations that reminded me of crayfish swirling in a pot of boiling water. It was close to midnight, and the sun of the Arctic high summer was throwing a glare on 4 Papa Alpha’s windshield. The pilot, Mad Mel Campbell, was smacking a stick of gum and wearing a grease-stained, pumpkin-orange flight suit with a .44 Magnum strapped to it. His face was wrapped in a gray beard, and the end of his nose was missing, hacked off years before during skin-cancer surgery. Earlier in the day, he’d given me the lowdown on his life so far: born in Nebraska, worked as a chopper pilot in ten different countries, two tours flying in Vietnam, three divorces. A guy who’s been through all that, I figured, wasn’t going to let the wind take him down. “There’s a three-crash phenomenon with helicopter pilots,” Mad Mel said. “If you can survive that many, you’re OK.”

Alaska Archaeology

11,000-to-13,600-year-old Mesa projectile points at the BLM lab in Fairbanks, Alaska

11,000-to-13,600-year-old Mesa projectile points at the BLM lab in Fairbanks, AlaskaAlaska Archaeology

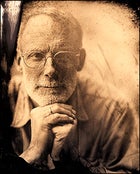

Archaeologist and point hunter Mike Kunz

Archaeologist and point hunter Mike KunzAlaska Archaeology

“How many have you had?”

“Three.”

Mad Mel was delivering me to Utukok, a remote temporary field camp in the western Brooks Range, where a team of U.S. Bureau of Land Management archaeologists was spending the summer searching for evidence of the first Americans. It is believed that these Siberian nomads crossed the Bering land bridge┬Śa dry-land passage between Asia and North America that became submerged approximately 10,000 years ago┬Śduring the last ice age, around 20,000 years ago, a time when you could stand in what is now Los Angeles and watch saber-toothed cats stalk mammoths. My journey had begun two days earlier at the Fort Wainwright Army Base, in Fairbanks, Alaska. There, I boarded a single-engine Cessna Caravan loaded with supplies and bound for “the Slope,” as locals call the North Slope, that vast expanse of largely unpeopled tundra lying between the Brooks Range and the Arctic Ocean. After a three-hour flight, the airplane dropped through a purple-rimmed hole in the clouds to land at a gravel airstrip on the tundra marked by a collection of tents, a parked helicopter, and a hand-painted sign reading, WHEN YOU ARE HERE, YOU’RE STILL NOWHERE. We were 150 miles north of the Arctic Circle, 160 miles west of the nearest road (which was gravel), and 200 miles from Barrow, Alaska, the closest town.

Getting that far was the easy part. Mad Mel and I then holed up in a tent for 24 hours while we waited for a break in the weather to attempt the final 125 miles to Utukok. That morning we’d made our first attempt but turned back 44 miles from our destination, in the face of a strong headwind.

“What’s that gauge you’re always looking at, Mel?” I asked.

“Fuel.”

“What about it?”

“With this headwind, we’ll be arriving with minus one gallons.”

We started our second attempt at 11 P.M., and one hour into the flight we were bouncing up and down and tacking into the wind, our heads turned slightly to the right to see where we were going. I wrapped my hands around my waist to keep my internal organs in their proper places. I didn’t relax until an hour later, when Mad Mel pointed out the windshield to a collection of eight tents in a narrow pass bordered by snowfields and steeply pitched mountains┬Śmy home for the next ten days.

PERHAPS MY EXCITEMENT about historical finds was getting the best of me, but when I arrived at Utukok I thought I’d stumbled across the half-frozen survivors of Franklin’s lost Northwest Passage expedition of the 1840s. Mad Mel and I were greeted by a team of weather-beaten archaeologists who looked as if they were engaged in a high-stakes beard-growing contest. There was Tony Baker, 62, a self-proclaimed “Indian-arrowhead nut” from Denver who’s been a BLM volunteer on the Slope every summer for the past seven years. Dale Slaughter, 67, is a project-based BLM employee and professional archaeologist based in Anchorage, and probably the only Alaskan who wears a beret. Standing in the door of a tent was Mystery Man, an amateur archaeologist who disdains public attention so much that he made me promise not to reveal his identity.

“I’m not here,” he said.

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“I mean I’m not here.”

Mystery Man’s voice and demeanor reminded me of Clint Eastwood from his spaghetti-western days, so I’m keeping my promise. The crew’s junior member was Myl├Ęne Paris├ę, a slender, dark-haired 25-year-old French-Canadian archaeology student and volunteer who’d become┬áfamous around Utukok for her apple crepes (which the guys called “creepies”).

The crew chief was Mike Kunz, a rugged-looking 64-year-old with wild white hair and a toothpick locked between his teeth. Kunz is a career archaeologist with the BLM’s Arctic Field Office, in Fairbanks. We were standing on the southern edge of his research domain, the National Petroleum Reserve┬ľAlaska (NPRA), now managed by the BLM, which is under federal mandate to survey the cultural and natural resources on all of its lands. In this case, that job has fallen to Kunz, and he’s got his work cut out for him: The 23-million-acre (think Indiana) NPRA is the largest undeveloped block of federally owned real estate in the United States. While the NPRA has yet to send a drop of oil to market, it’s going to happen soon┬Świthin years rather than decades. One obstacle is that the land hasn’t been completely surveyed for cultural resources. It’s as if the archaeologists are there to document an old house while bulldozers wait outside to start leveling it.

For now, there are no exploratory drill rigs or fueling stations in sight, and everywhere you look it’s just water, mountain, and tundra. “The reserve is 99.9 percent undisturbed by humans,” Kunz said one day when we were doing some aerial recon. “Except for some different plants and animals down there, it looks the same as it did during the late Pleistocene.”

The late Pleistocene epoch (125,000 to 10,000 years ago) is of big-time interest to Kunz because it holds the key to who the first Americans were and how they lived. Currently, the oldest scientifically accepted dates for human occupation of the Western Hemisphere are clustered around 13,000 to 14,000 years ago. But some archaeologists will tell you that there should be human artifacts almost twice that old, and they’d like to find them. “Someone wants the biggest truck, someone wants the most expensive TV,” explained Kunz. “Many archaeologists would love to say, ‘I have the oldest date for humans in the New World.'” Kunz will show you where many of those artifacts might come from┬Śright here in the NPRA.

As a graduate student in the mid-sixties, Kunz worked at the Blackwater Draw site, near Clovis, New Mexico, where spear points were found among mammoth skeletons dating to 13,300 years ago. The hunters are known as the Clovis culture, and subsequent discoveries suggest that these people were the first to widely settle North America. As such, their signature points are extraordinarily valuable. Recently, a private collector bought the well-known Fenn Cache, comprising 23 Clovis points and other artifacts, from another collector for a rumored $1 million plus. The initial discovery of Clovis, along with other groups of ice-age hunters, known collectively as Paleo-Indians, presented a mystery about the peopling of the Americas. If man entered the New World at the oldest archaeological site, that would mean he popped out of the ground on the Great Plains. “It was like these people spontaneously generated,” explained Kunz. Some scientists guessed that Paleo-Indians originated from Pacific Islanders blown astray. Most argued Siberia or Western Europe. Some even suggested outer space. But each hypothesis was plagued by a lack of proof.

Then, in 1978, while Kunz was doing archaeological survey work on the NPRA, which occupies land that was once the doormat for the Bering land bridge, he made an astounding discovery on top of a prominent bluff. “When I walked up there,” he said, “the first thing I saw, I said, ‘This looks a lot like a Paleo-Indian point.’ Then I found another one. And another one.”

Kunz’s team excavated 150 projectile points dating all the way back to 13,600 years ago. While the area was not the oldest known site in North America, Kunz was the first to find tangible proof of a connection between the Bering land bridge and Paleo-Indians of the High Plains. In 1993, he published his findings in Science, and his discovery was covered by everyone from Sam Donaldson to the BBC.

But the second piece to the Paleo-Indian puzzle remains unresolved: Did humans cross the Bering land bridge into the New World thousands of years earlier than 13,600 years ago? A discovery of that importance could completely rewrite our understanding of human history in the New World. Kunz thinks it’s possible, and he and his teams have been looking for evidence in the NPRA.

“There’s a site in Siberia that’s 30,000 years old,” he told me, referring to the Yana site, discovered in 1993. “Siberia’s only 60 miles away from Alaska. Granted, these Siberians didn’t wake up that day and say, ‘Fred, let’s go toward North America.’ But they were on the path. I wouldn’t be surprised to find something that’s 20,000 years old out here. Maybe older. It’s going to be very difficult. A lot of the earliest sites are now underwater. But we could find them. I think we will find them. It’s just a matter of time.”

OUR CAMP AT UTUKOK was bare-bones. Everything had to be flown in and out by helicopters with extremely limited payload space. Everyone got their own North Face tent for privacy; communal space was provided by a canvas cook tent with a propane stove. As far as showers went, there was a deep hole in a creek about a mile from camp. The bathroom was an open-front plywood windbreak surrounding a plastic-lined hole in the ground.

Despite the lack of amenities, working at Utukok quickly became my favorite thing in the world to do. In the mornings (since it never got dark, “morning” seemed completely arbitrary), we’d get up and meet in the main tent. Over breakfast we’d look at maps. Mystery Man plotted out survey areas based on topography and watercourses, and conferred with Mad Mel about flight routes and landing zones. Slaughter and Mystery Man would head to one destination while Baker, Myl├Ęne, and I headed to another.

“Arrowheads don’t yell out, ‘Here I am! Come pick me up,’ ” Baker explained one day. He was walking ahead of Myl├Ęne and me about ten miles from camp, where Mad Mel had dropped us off along an unnamed tributary of the Utukok River. The crew had divided the entire NPRA into sections based on major watercourses, and this summer they were concentrating on the mountains to the south of the Utukok.

When the oldest site in the New World is found, it will probably be thanks to the shrewd eye of an arrowhead hunter like Baker. While much of Kunz’s time is sucked up by managerial duties, each summer Baker is on the ground every day for a month or more. His grandfather and father were both archaeologists, and 17 years ago, when he was 45 and still working as an engineer, he earned a degree in anthropology from the University of Colorado at Denver to follow in their footsteps. Baker has found arrowheads in a dozen states; he and his father have amassed a collection of some 5,000 stone artifacts.

As I walked behind Baker, I marveled at his attentiveness. In a land of constant threats from rockslides and grizzly bears, he keeps his eyes locked on the ground as though a cable connected his chin to his chest. In the NPRA, Baker has seen everything from 2,000-year-old Eskimo artifacts to a Russian shotgun from the 1850s. But he’s primarily interested in rock.

“What kind of rock are we looking for?” I asked.

“You’re walking on it. It’s this gray stuff. These nodule-shaped outcroppings are all chert, a tool-grade stone. But none of these rocks have been worked.”

When Baker says a rock’s been worked, he means that it’s been modified by a human. Finding such artifacts is a complex skill. “First I’m looking for rocks that are out of place,” he said. “If I’m on a hilltop covered in crushed shale and there’s a lone, single flake of chert there, it didn’t get up and walk there. Someone carried it in. So when I see a rock like that, it gets my interest.”

We made our way across a steep slope covered in lichen. “There’s nothing here,” he said. “You wouldn’t want to sit here and work on rocks. Ten thousand years ago, or whenever, people camped in the same places where you’d camp now: level areas with smooth ground, a good view of the surrounding country, access to fuel for fires, maybe overlooking where a couple rivers come together.” Baker pointed to a bluff about a half-mile ahead. “We’ll find something up there,” he said.

And we did. The moment we climbed to the top of the bluff, Baker called Myl├Ęne and me. “This is a flake scatter,” he said. The ground was covered in flakes of gray chert the size of a pinkie nail┬Śthe by-product of tool construction. Baker picked up a piece the size of the bottom of a coffee mug. “The surface marks that look like clamshells are the result of conchoidal fractures. Rocks can break from freezing and thawing, animals step on them┬Śall kinds of things happen┬Śbut when you see a conchoidal fracture, you know it’s a man that did it.”

Random flakes don’t excite Baker because they’re not diagnostic; that is, the shape of the artifact does not signify the time period when it was produced. To a trained eye, the shape of a complete point┬Śor even a broken tip┬Ścan tell you whether it’s of ice-age vintage. And Baker reminded me many times, “I’m only interested in the really old shit.”

Seconds later, Myl├Ęne picked up a rock. “Hey!” she yelled.

“Oh, looky there,” said Baker. “You see how flakes were knocked off on both sides of that? That’s what we call a biface.”

“Is that how Clovis made them?”

“Yes, but so did many other groups.”

He looked around for another minute. “OK,” he said, “let’s record this sucker.” We wrote down the number of artifacts we found, along with their location and a brief description of topography and ground cover. Myl├Ęne paced off the bluff’s diameter. “Fifty meters,” she said. Before we left, she photographed and sketched the biface, then crouched down and carefully put the stone back where she’d found it. The archaeologists do not remove artifacts during survey work. I asked Baker, “Aren’t you worried that something will happen if you just leave it lying around? What if someone steals it?”

“This is the best warehouse in the world,” he said. “These have been here thousands of years and no one’s fucked with ’em yet. It takes big bucks to get up here. Plus it’s illegal to take stuff from federal land. It already has an owner: you and me.”

As we walked off the bluff, I asked Baker, “Is this an interesting site? Is it old?”

“There’s nothing diagnostic,” he said. “All I can tell you is that some person was up here sometime in the past, banging the hell out of these rocks.”

MYL├łNE AND I WERE like Baker’s hunting dogs, and we dutifully followed directions. The closest I actually came to making my own stupendous find was when Baker pointed to a high, flat-topped ridge above the Kogruk Creek. “Why don’t you two youngsters run up there and take a look,” he yelled to Myl├Ęne and me. When I got to the top, I could see two large bifaces and a scattering of flakes. My pulse quickened.

I don’t know why, but I just knew this site was really old. I felt like the ground was speaking to me. I waved to Baker, and then quickly regretted it. I wanted to hog for myself whatever archaeological glory this site had. As Baker started up the hill, I dropped to my knees and began investigating the stones for a point that might be diagnostic. Myl├Ęne was searching the ground 20 yards away and angling in my direction. A frenzied, competitive feeling came over me. As I scoured the area, I fantasized about my discovery of a totally unknown, brand-new ice-age occupation that would be named the Steve Rinella Culture. I scoured the ridgetop in fast motion. I looked the whole thing over.

Or so I thought. The moment Baker crested, he walked right up to where I’d just been and said, “Oh, looky here. A Sluiceway.”

For the archaeologists, recovering a Sluiceway point is like finding clues to a sunken, gold-laden Spanish galleon. The points were undoubtedly produced by Pleistocene hunters, but there’s some confusion about them. Kunz says Sluiceway points resemble the points found on his Mesa site, except that they “look like they’re on steroids.” There are two competing theories about Sluiceway. First, that they were produced by the same people who occupied the Mesa site, and the difference in shape merely suggests a different hunting purpose, like maybe a different species of game or a different type of spear. The second theory suggests that the points may have come from a culture with much closer ties to Siberia, which means that locations containing Sluiceway points might prove to be considerably older.

I was overcome with jealousy at Baker’s find, but I was also jumping up and down with excitement. He had said we needed to find something diagnostic, and here it was. The next step is to excavate the site for once-living material that can be carbon-dated, such as charcoal from campfires.

“So?” I asked Baker. “You think we’ll dig this site?”

He looked around. “No.” He then explained that excavations require lots of manpower and money, and the archaeologists needed solid evidence suggesting they’d find datable material that was directly associated with the artifacts. The summer before, the crew spent weeks digging a Sluiceway campsite and never recovered a datable piece of material.

“But we have evidence,” I said.

“Just because we got a Sluiceway point doesn’t mean there was a Sluiceway camp here,” he said.

Kunz later explained to me that the crew has found 200 archaeological sites near the Utukok River alone. Of those, he considers only two worthy of future excavation.

Baker replaced the Sluiceway as carefully as you’d handle an injured bird. I felt like cheering for the point’s perseverance in the face of time.

WHILE I WAS IN the Arctic, it was never far from my mind that, in some ways, the archaeologists’ work has more to do with Big Oil than with early Americans. The team members have developed various ways to deal with this. Dale Slaughter practices willful denial. “I don’t like to see this work as a prelude to anything,” he says. Baker had his own pragmatic way of looking at it: “If I don’t do this, they’ll just get some other jerk-off to do it, and he won’t do as good of a job as I do.” Mystery Man told me, “As far as I’m concerned, these artifacts could sit here forever, unrecognized, if they weren’t compromised by oil exploration and drilling. But they are compromised, so we’ve got to do this. What makes me uncomfortable is that the oil companies suck off our work.”

That’s true. Infrastructure set up in the seventies as part of the archaeological survey┬Śscattered camps, helicopter equipment, fuel depots┬Śis routinely utilized by oil-company geologists and engineers. As a career BLM man, Mike Kunz sees it this way: “You can’t just throw your pack in your pickup and do archaeology out here. Those helicopters are our pickups, and they’re expensive. A helicopter costs $2,700 a day to rent, whether it turns a blade or not, plus $550 per hour of flight. Helicopter fuel costs $6.80 a gallon, delivered. We wouldn’t be able to do this work without money from oil and gas leases. One lease can pay for all this. That’s just the way it is in the Arctic. If you don’t scratch each other’s backs, nothing will get done.”

There’s a terrible irony in using fossil-fuel revenues to finance research about the ice age. As my time hunting arrowheads in the Arctic slipped by, I became nervous that I would miss my chance to find an ice-age artifact in a place that allowed me to envision the world in the same way that the first Americans saw it, a way that may no longer exist in the not so distant future.

When my last day in the Arctic arrived, rainstorms and fog came with it. Mad Mel announced that the helicopter was grounded. I thought my hopes of finding a major artifact were crushed, but later in the day I was given a final chance. During a break in the rain, Baker offered to take Myl├Ęne and me to a site along the Utukok where Mystery Man had found a Sluiceway point earlier that summer. We hiked a couple miles through the fog. The three of us paced around in circles at the site.

“It should be right here,” said Baker. He pointed to an exposed shard of rock. I reached down and took the rock between my thumb and forefinger, then pulled the piece free of the ground. The projectile point was perfectly sharp and nearly intact, except for a slight break near the tip. It was about as long as my pinkie, and it fit my hand as comfortably as a handshake.

The rain kicked up as we admired the point. We were soaked. Myl├Ęne and Baker headed toward camp, but I stayed behind to keep looking. Eventually the fog got so thick that I was worried about finding my way back. I started toward camp, but the ground dropped away toward a tangle of willows right where I thought it should be rising up toward a hill. I turned around and tried again. Still no hill. A panic rose in my chest. I could walk out here for months and never be found.

When the fog lifted, I could see the hill that Baker and I had come down. I had to laugh at myself. What would the ice-age hunters have thought about my little panic attack? As I walked back to camp, I was already thinking about next summer. I wanted to return, to keep looking. As I stooped down to touch a piece of chipped stone that caught my eye, I thought of something that Mike Kunz had told me: It’s just a matter of time.