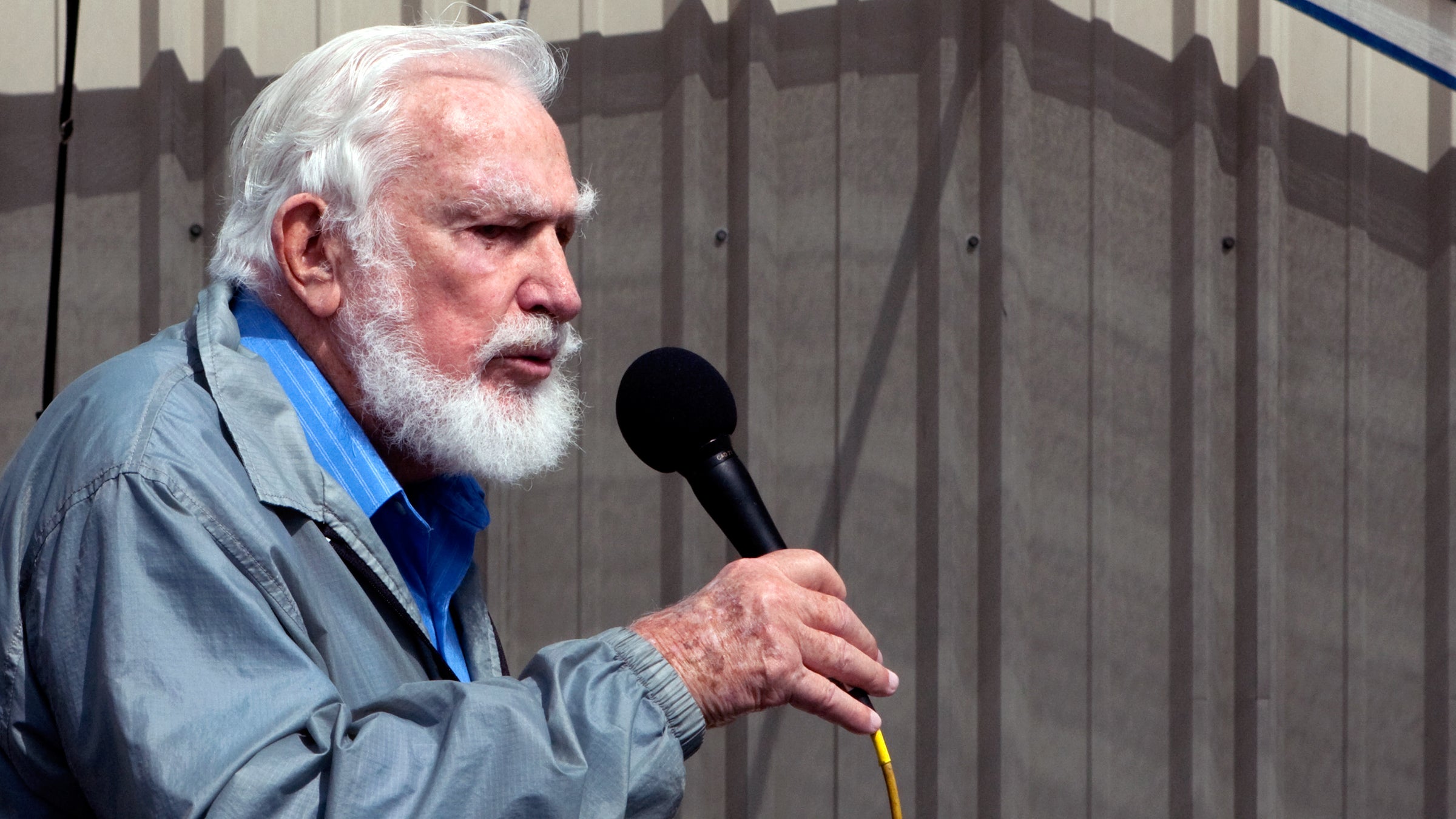

Martin Litton, the early conservationist, crusader, Sierra Club board member, and father of commercial river guiding in the Grand Canyon, has died.

Litton was many things during the past century. During World War II, as a glider pilot, he delivered American troops into German-occupied France. After the war, back in his native California, Litton worked at the Los Angeles Times, where he first found his voice writing fiery articles railing against the extractive industries that were rampantly and wantonly destroying California’s forests and rivers. It’s in that vein that Litton delivered his greatest contribution to society—not a tangible thing that you can touch or see, but the preservation of the Grand Canyon itself.

Litton first floated the Grand Canyon with his wife in 1955. He had found his calling, and in 1971 founded Grand Canyon Dories, which has since merged with OARS, the only guiding outfit on the river that uses exclusively wooden dories.

Starting in 1963, Litton, along with David Brower, the Sierra Club’s executive director at the time, formed the core of the lobbying effort that successfully derailed the Bureau of Reclamation’s plans for two dams—the Bridge Canyon Dam and Marble Canyon Dam—that were slated for construction between lakes Powell and Mead, within the last 277-mile running stretch of the Grand Canyon. He and Brower took out full-page ads in the New York Times decrying the dams, actions that immediately got the Sierra Club investigated by the IRS. No matter, he and Brower next launched what might have been the first social-media campaign, taking their message to the Weekly Reader, a national newspaper widely distributed to elementary schools. In 1968, the plan to flood the Grand Canyon was scrapped.

As ���ϳԹ��� contributing editor Kevin Fedarko detailed in his book on the Grand Canyon, The Emerald Mile:

Historians often minimize or discount the impact that any one individual can have on human destiny—and for good reason. Given the broad tides in the affairs of men, and the complexity of the forces that shape and change history, it is almost always a mistake to ascribe too much significance to the actions of a single person. But even the most jaded observer can concede that, every now and then, a man or woman steps up to the plate and takes a mighty swing that clears the bases and fundamentally changes the game. … This is what Litton achieved.

Litton was 97.