THE SOUTHERN Ocean has long been the sailor’s obsession. Its first true promoter, 18th-century explorer Captain James Cook, could hardly fail to be inspired by its wrath. Through the years the tempestuous body of water became infamous for treating mercilessly the ships and men who dared venture into it, a place associated more with survival than sport. In the 1960s, the first proposals to race sailboats through this nether region of marauding weather bombs and tumbling liquid mountains were derided by many as invitations to a mass drowning. Yet today the Southern Ocean is racing’s most hallowed passage, luring sailors with the promise of wild surfing runs, dramatic seascapes, and uncommon isolation. “It’s just the best sailing you can do anywhere on the planet,” says Paul Cayard, an America’s Cup sailor and inshore racer who got his first taste of the stormy seas during the 19971998 Whitbread Round the World Race. “Doing a complete round-the-world race with all the Southern Ocean parts is the ultimate test of seamanship.”

Modern navigation and weather-forecasting technology, along with lightning-quick boat designs, have tempered the raw fear of sailors, who still max out the adrenaline. So it should come as no surprise that the watery proving ground south of the 40th parallel is currently in the midst of the greatest sustained racing assault in history.

It began last November as 24 Vendée Globe racers set out to solo from France nonstop around the world in high-powered 50- to 60-foot monohulls; 19 would go on to slug it out over the more than 7,800 miles of heaving water between the Cape of Good Hope and the treacherous sentinel of Cape Horn. On the eve of the new year, six fully crewed maxi-catamarans of The Race left Barcelona to lap up their wakes at mind-boggling speeds that topped out at more than 45 miles per hour. And this September, seven or more monohulls of the Volvo Ocean Race (née Whitbread) will depart Southampton, England,to trace roughly the same route. “In 1968 we did not know it was possible,” says Britain’s Sir Robin Knox-Johnston, who in that year became the first sailor ever to circumnavigate via the Southern Ocean without stopping for assistance (it took him 313 days). “Nowadays the pressure is from very close competition,” says Knox-Johnston. “The sailors these days are the sharp end of a team, like a racing-car driver.”

Unfortunately, sailors on the sharp end still die. In the 19961997 Vendée Globe, Canadian Gerry Roufs was swallowed by the seas on the approach to Cape Horn, while three of his rivals were lucky to escape overturned boats with their lives. So far this year the only casualties have been shattered records. On February 10, Vendée Globe winner Michel Desjoyeaux, a 35-year-old French sailor, triumphed over the largest and most competitive Vendée fleet in four runnings with a circumnavigation that took just 93 days, 4 hours, and beat the previous monohull record by almost two weeks. Just one day later, Britain’s Ellen MacArthur, a 25-year-oldwunderkind sailing her first Vendée, posted the second-fastest time in history. Then, on March 3, Club Med, a 110-foot catamaran co-skippered by Kiwi Grant Dalton (with six round-the-world races to his credit) won the inaugural edition of The Race in just 62 days, seven hours, almost nine days faster than any previous nonstop circumnavigation.

Speed, in fact, has become a legitimate Southern Ocean danger. American skipper Cam Lewis, a notorious hard-charger, got religion 19 days into The Race when his maxi-cat Team ���ϳԹ��� speared a wave at around 30 knots. The impact smacked the big boat to a sudden stop, inflicting severe neck and back injuries on two crewmen (uninjured co-navigator Larry Rosenfeld later compared the experience to a bus crash). The Team ���ϳԹ��� crew made repairs in Cape Town and eventually completed the circumnavigation–20 days, 12 hours behind Club Med. Yves Parlier, a 40-year-old Vendée Globe competitor, received a similar lesson in prudent seamanship, but countered with the sort of heroic gesture that the Southern Ocean seems to inspire. Pushing too hard while trying to retake the lead from Desjoyeaux, Parlier’s mast crumpled to the deck when a squall hit his Aquitaine Innovations off Australia. At the time, Parlier had 7,000 miles of Southern Ocean in front of him, and 14,500 miles to the finish in France. Instead of withdrawing, Parlier coolly jury-rigged a 60-foot mast and sailed on, fishing and eating seaweed to ward off starvation during a circumnavigation that eventually kept him at sea more than 126 days. “What Yves has done is bigger than the race,” said Philippe Jeantot, founder of the Vendée. “For me he has reached back to the original spirit of the race, which was adventure.”

Nowhere Fast

Competitive indoor rowing gains a curious cult following

“WHERE’S maintenance?” a frantic volunteer yells over the jetlike whirr of 100 athletes zipping back and forth on stationary rowing ergometers inside Boston’s Reggie Lewis Athletic Center.”I’ve got piles of puke on 43 and 67!”

Victory here at the World Indoor Rowing Championships is a digital affair; each of the winners pulls hard enough to advance his or her computer-icon boat the equivalent of 2,000 meters and across a TV-screen finish line. Yet competitors pay for their virtual boat speed in decidedly human terms, with lactic-acid burn, carbon lungs, and yes, vomit, soaked up as necessary with cat litter carried about in ten-quart buckets labeled “Barf Control.”

Curiously, many here row only indoors. They may never know the creak of a straining oar, the sound of water dripping off a blade as it glides back for the next stroke, or the sweet swing of a crew in synch, but this new breed of erg-centric oarsmen and -women is nevertheless swelling the ranks of this Boston event, and more than 40 indoor regattas nationwide. In 1982, just 60 athletes, mostly Bostonians, participated in what was then called the C.R.A.S.H.-B Sprints. This February’s showdown pulled in 1,800 rowers, from nations as far afield as Turkey. Similar events will take place next winter in Portugal, Taiwan, and Sweden.

All of this spells a corporate fairy tale for Morrisville, Vermontbased Concept2, builders of the infernal machines. The firm reports double-digit sales growth for 20 of its 25 years in business. Yet even devotees scratch their heads over the sport’s inexplicable appeal. The championships “started out as a joke,” says Concept2 indoor race coordinator Robert Brody. “Now there are people who train for this all year round.” With evident sarcasm, he adds, “C’mon, get a life!”

View from the Summit: Blurry

Alpinists laud the convenience of laser vision correction, but is there a price to pay?

MYOPIC MOUNTAINEERS itching to ditch their contact lenses or prescription goggles for laser vision correction might want to wait before emptying their piggy banks. A study in the March edition of the journal Ophthalmology suggests prolonged exposure to lack of oxygen at high altitudes may cause temporary blurring of distance vision for LASIK patients who are “involved in high altitude activities for extended periods, such as mountain climbers [and] skiers.” Researchers, who strapped airtight goggles onto 20 formerly nearsighted subjects and simulated sea level in one eye and drained the oxygen from the other, noted a gradual swelling in the hypoxic eyes that resulted in a mild distortion of distance vision.

Mark Nelson, one of the study’s coauthors, ballparks the shift from 20/20 vision to 20/80 at its worst. Even so, Geoff Tabin, an ophthalmologist who completed the Seven Summits in 1990, believes the benefits of the popular procedure (see “The Fit List”) still outweigh the risks of iced-up contacts or foggy goggles. Rich Emmett, a Louisville, Kentucky, attorney who went under the beam in April 2000, agrees. While summiting Denali last June, he experienced a visual near-whiteout, although his sight soon recovered. “Sure, it’s a trade-off,” says Emmett, “But to be able to see the vistas from the top of Denali—I wouldn’t trade that for nothin’.”

Knobby Fires

Is there a link between a spate of Phoenix arson attacks and mountain bikers’ passion for local singletrack?

HIGH ABOVE downtown Phoenix, Doug Thompson and Brian Perkins are out thrashing some Sunday-afternoon singletrack. The two riders fling their mountain bikes over the crest of a ridge, skirt a bend littered with gravel—and stop dead up against an orange fence plastered with signs that threaten, “Do Not Enter,” “Private Land,” and “No Trespassing.”

It’s frustrating. Open to the public just a few weeks earlier, this spur of Trail 100 is now completely off-limits. But what Thompson and Perkins find truly galling lies just beyond the barrier that separates the Phoenix Mountains Preserve from the tendrils of the surrounding city. The hillside here has been bulldozed back to make room for the foundation of a luxury home. Next to this, an empty lot awaits another high-end hacienda. And behind that is a third site, a nearly complete mansion studded with extravagant features—including a “garage mahal,” real-estate parlance for a carport that holds five vehicles—intended to seduce the cash-flush newcomers who helped make Phoenix the nation’s second-fastest-growing city in the 1990s.

Not that Thompson and Perkins are in any position to cry foul. Both are very profitably piggybacking on the city’s rapid expansion—Thompson, 41, designs fiber-optic networks for a large telecommunications company, while Perkins is a successful architectural designer. “I don’t want to be a hypocrite,” says Perkins, 35, all too aware of the irony of his own resentment. “But we never even got to ride this trail. That really sucks.”

APPARENTLY, others agree. Last December, someone set fire to a house being built on the site, burning it to the ground. It was the eighth in a string of 11 arson attacks in Phoenix and neighboring Scottsdale since January 1998, all of which targeted luxury homes under construction adjacent to recreational wilderness. Despite an $88,000 bounty for information, partly posted by area homeowners, an investigative task force—run by at least six government agencies including the FBI—has failed to generate a single arrest. But on January 25, local reporter James Hibberd produced an extraordinary scoop for the New Times, the city’s weekly alternative paper, when a man who claimed responsibility for the fires allowed Hibberd to interview him in a public park.

The source declined to give his name, but described himself as a management professional working in downtown Phoenix. He established his legitimacy by describing two notes that he had left behind at fire sites—letters that the investigators had not made public. He said he belongs to a four-person group called the Coalition to Save the Preserves, and he explained that he and his cohorts had scouted out construction sites during mountain-biking excursions and then returned in the middle of the night to set them on fire. Why? “Because they’re encroaching on hiking and biking trails,” he told Hibberd, adding, “They’re an obnoxious reminder that there is no growth plan.”

On this latter point, the arsonist may have drawn approving nods from groups currently fighting a losing grassroots battle against the explosion of subdivisions, parking lots, and golf courses that have gobbled up the Sonoran Desert around Phoenix at the rate of an acre an hour for the past decade. Last June, a coalition of environmental organizations—including the Sierra Club—filed a citizens’ ballot initiative that would have set up boundaries around cities all over the state, beyond which development could not occur—a scheme inspired by a highly successful growth-control plan already in place in Portland, Oregon. When polls indicated that 68 percent of the public supported the proposal, an alliance of developers, builders’ groups, and pro-growth city and state politicians launched a media campaign to convince voters that this “Sierra Club Secret Initiative” would rob Phoenix of 200,000 jobs and “ruin Arizona’s economy.” On November 7, the measure was defeated.

Meanwhile, the New Times story created a firestorm of its own, enraging law enforcement groups, which cut off all media interviews and unsuccessfully pursued court-ordered access to Hibberd’s notes. The FBI is not likely to ease up anytime soon—the Bureau badly needs a success story. In the past year, ecoterrorists have destroyed bioengineered crops in Oregon, while the radical Earth Liberation Front launched still unsolved arson attacks against sprawl in Indiana, Colorado, and New York. But if the stated motives of the CSP are genuine, the Phoenix firebugs may have launched something altogether new: America’s first wave of recreational ecoterrorism—felony acts in the name of protecting trails.

AS THIS article went to press, the playgrounds in and around Phoenix were quiet. No homes had been burned since January, no arrests had been made, and the trail networks in the preserve remained under round-the-clock police surveillance by helicopters and plainclothes cops. Amid the jittery stalemate, more than two dozen Phoenix bikers approached by ���ϳԹ��� on the trails in March denounced the arsonists’ tactics as misguided, but expressed sympathy with the frustrations that provoked these crimes. And yet, in voicing such views, some cyclists unwittingly revealed that they are as dependent upon development as anyone else.

“Developers are destroying the most beautiful parts of the desert,” says Josh Maule, 22, who’s out for a ride with several friends. “I hope they all burn in hell!”

“Dude,” interrupts Josh’s friend, Scott Keller, 20. “Isn’t your dad. . . a developer?”

“No way!” replies Josh. “Well, I mean, he sort of is. He’s working on his first million-dollar project right now. He does custom homes—but he isn’t putting up, like, 50 houses a day in the desert.”

Josh’s defense gets lost amid roars of laughter. The riders pick up their bikes, click into their pedals, and barnstorm up the trail.

Uncivil Disobedience

A brief history of environmentally motivated monkeywrenching

Early- to mid-1970s Arizona’s “Eco-Raiders,” Minnesota’s “Bolt Weevils,” and Chicago’s lone saboteur “The Fox” vandalize corporate and industrial sites, give birth to modern ecotage.

1975 Edward Abbey’s The Monkey Wrench Gang romanticizes ecoterrorism.

1980 Earth First! founded. Dave Foreman and four fellow eco-radicals inaugurate a decadelong campaign of civil disobedience and monkeywrenching.

1985 Ecodefense!, Foreman’s how-to manual, offers tips on tree spiking, power-line slicing.

1987 Cloverdale, California: The spike hits the saw. A 23-year-old mill worker is hospitalized with facial wounds when his blade shatters upon hitting a 60-penny nail embedded in a redwood.

1989 FBI arrests Foreman for Arizona ecotage. Charges are eventually dropped.

October 1996 Detroit, Oregon: Earth Liberation Front debuts, torching Forest Service truck. ELF allies with animal-rights group Animal Liberation Front soon after.

October 1998 Vail, Colorado: Predawn arson attack on Vail ski resort turns $12 million lodge to charcoal. ELF claims responsibility.

December 1999 Monmouth, Oregon: $1 million fire in Boise Cascade office claimed by ELF.

December 1999 Lansing, Michigan: ELF widens purview to include genetic engineering, torches office in MSU agriculture building.

January 2000 Bloomington, Indiana: ELF burns house under construction. Mandate widens to target sprawl.

Nov.Dec. 2000 ELF roasts houses in Niwot, Colorado, and Long Island, New York.

February 2001 Visalia, California: ELF claims arson of cotton gin to protest genetically altered cotton.

Loot

���ϳԹ��� Essentials, To Go

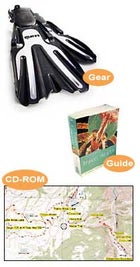

The new Volo, designed by the Italian scuba maestros at Mares, is the Maserati of diving fins. The flipper’s pivoting blades and channeled deck were designed to allow you to kick more efficiently than with traditional fins, which means you use less energy while ripping past your flailing friends. A slider catch lets you adjust strap tension with one finger, plus they’re more stylish than a pair of Bruno Maglis. $200 (booties required);

Guide: Leishmaniasis, African trypanosomiasis—the world is full of nasty bugs. But The Rough Guide to Travel Health—a thorough country-by-country compendium of parasitic, viral, and bacterial beasties—may help you fend them off. $8;

CD-ROM: It took two summers of fieldwork to create The Colorado Trail, iGage’s new CD-ROM atlas of the famed 487-mile route from Denver to Durango. Over 100 high-resolution maps–featuring 466,000 GPS-plotted trail points–make this the most accurate rendering of the CT ever. $40;

Gear: With nine hours of halogen light and a 12-hour backup LED, Black Diamond’s new 8.5-ounce Spaceshot headlamp could save your bacon should your easy day hike unexpectedly morph into a pitch-black overnighter. $60;

Video: You, too, can nail a wheelie drop. Or at least you can pull a graceful endo trying, having first studied West Coast Style-Mountain Biking, the first vid from Vancouver’s West Coast School of Mountain Biking. Watch, rewind, repeat. $17;

Guide: Surprisingly, over two-thirds of Japan is mountainous terrain, and Lonely Planet’s Hiking in Japan will help get you out there into the (hopefully) Pokémon-free zone. Choose from 70 day hikes and backpacking trips in the island nation’s unspoiled backcountry—including climbs in the Chubu region’s South Alps. $20;

CD: (not pictured) Get in the mood for your next exotic destination with Putumayo World Music’s latest compilation, Gardens of Eden. This musical tribute to the last pristine places on earth includes upbeat selections from Papua New Guinea, Madagascar, Tibet, and other Shangri-las. $16;

Dot.gone

Tracking the short, sad life of online outdoor retailers

THIS WAS THE dream: The Web would be the ultimate gear shop. It seemed like a good idea two years ago, when a glut of investment cash encouraged entrepreneurs to launch scores of Web-based “e-tailers”–such as Gear.com, Altrec.com, and PlanetOutdoors.com. Many of these businesses spent heavily on advertising only to find their URLs forgotten by would-be customers overwhelmed with choices and longing to actually see, feel, and try on the goods they would trust with their very lives.

As dotcom losses mounted, investor confidence finally began to falter, and last fall the money evaporated like a Serengeti watering hole. It wasn't just swag sites, either. Webcaster Quokka.com called it quits at press time in mid-April, canning all but a handful of its remaining 220 staff. As the company reportedly prepared a bankruptcy filing, Nasdaq suspended trading of its stock (from a one-time high of $19, shares had dipped to 23 cents). Survivors remain, but the damage has been fast and furious. Below, a partial list of casualties, and an outlook for those still clicking along.

Gear.com

Launched: October 1998

Brands sold: Helly Hansen, Dynastar, Asolo, Dunlop, Wilson

Life span: 25 months

June 2000 Gear.com dumps 20 people.

July 2000 Gear.com announces it has raised $12 million from venture capitalists, and says it will spend the dough to expand its product offerings to more than 250,000 items.

Septeber 2000 The firm unloads another 22 people, slicing its original staff in half.

November 2000 Web wholesaler Overstock.com purchases Gear.com's $14 million inventory and folds it into its sporting-goods department. Gear.com employees receive a one-month bonus if they stay at Overstock through Christmas season.

PlanetOutdoors.com

Launched: August 1999

Brands sold: Patagonia, Black Diamond, The North Face

Life span: 12 months

June 2000 Company launches spinoff Womenoutdoors.com site. Weeks later, it cans 22 of 100 staffers.

MVP.com

Launched: January 2000

Brands sold: Adidas, New Balance, Shimano, Oakley

Life span: 12 months

December 1999 MVP.com seals a ten-year, $120 million marketing deal with SportsLine, allowing MVP to link to SportsLine's Web pages.

January 2000 MVP.com kicks off a $50 million marketing plan starring football legend John Elway and pros Michael Jordan and Wayne Gretzky.

August 2000 MVP.com buys PlanetOutdoors.com for undisclosed sum.

November 2000 MVP.com misses a $5 million payment owed to SportsLine. SportsLine dumps MVP.

December 2000 MVP.com cuts its staff in half, slashing 79 jobs.

January 2001 MVP.com unloads its domain names and customer database to SportsLine and turfs 36 staffers.

Fogdog.com

Launched: November 1998

Brands sold: Callaway, Nike, Columbia, Converse, K-Swiss

Life span: 25 months

May 2000 FogDog chairman Brett Allsop resigns. The firm cites “market conditions.”

July 2000 FogDog president Tim Joyce resigns his reported $280,000-per-year position, citing personal reasons.

July 2000 The stock sinks below a dollar.

October 2000 The company reports losses of $8.5 million on revenues of $5.9 million. Stock sinks to 23 cents. Fogdog dismisses 20 staffers.

December 2000 FogDog cries uncle and sells itself to Globalsports.com—which operates Web sites for sports retailers—for $38.4 million. Almost all of FogDog.com's 140 employees get sacked, save 25 engineers.

Altrec.com

Launched: March 1999

Brands sold: Nike, Marmot, The North Face, Patagonia, Mountainsmith

Life span: 27 months and counting

April 2000 Atlanta-based Cox Interactive Media sells Greatoutdoors.com to Altrec.com for $10.5 million. The deal doubles Altrec.com's traffic.

June 2000 Altrec.com teams with National Geographic to create Ontheamericantrail.com, a site offering virtual tours of the nation's most famous trails.

June 2000 Altrec.com inks agreement with Virtuoso.com, a network of 258 travel agencies.

October 2000 Gomez, a Web-site ratings firm, calls Altrec.com the number-one outdoor-enthusiast site on the Net.

November 2000 After six months on the job, Altrec president John Wyatt resigns–following 16 employees dismissed since September.

January 2001 As one of the last gear sites left standing, Altrec expects to be in the black by year-end. Development VP Shannon Stowell: “We're really pleased with how the market has shaken out.” No kidding.