It happens to the best of us. Somewhere in between those “everything's possible” yearsÔÇöwhen the future spreads out like an endless invite to adventureÔÇöand reality, our dreams all too easily get crowded out by the dolorous day-to-day and the need to make ends meet. All the cool things we thought we'd beÔÇömountain climber/novelist/musician! skier/doctor/wilderness guide!ÔÇöstart looking impossibly out of reach, especially when we read the statistics. Only about 45 percent of Americans are satisfied with their job, surveys show, and nearly all are seeking more time off and a better balance between work and leisure. But then we hear about someone with an epic formula: They've gone for the stoke without going broke, and they're having a blast in the meantime. What's their secret?

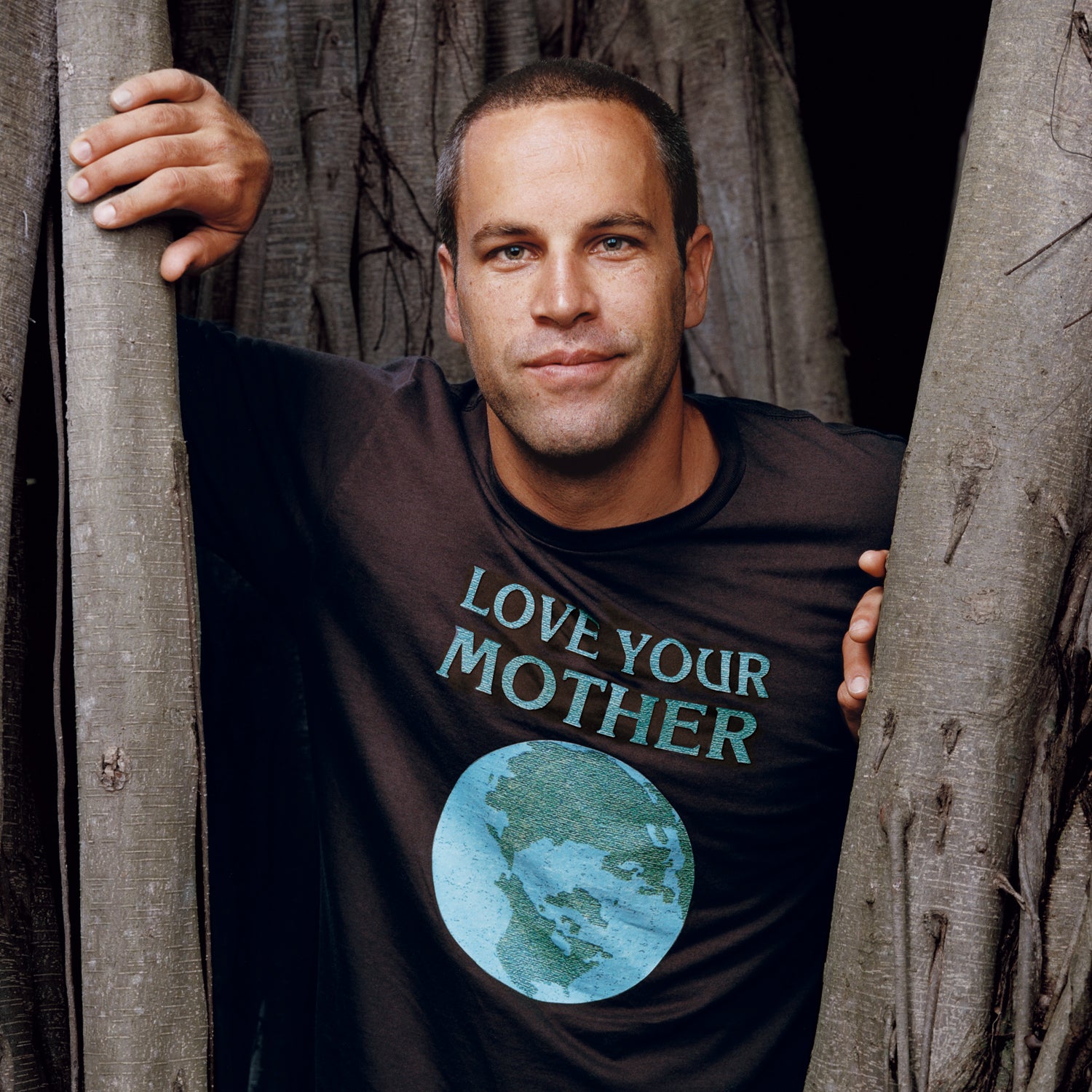

Jack

WHEN PASSION PAYS: He may be a rock-star millionaire with three platinum albums, but Jack Johnson still makes time for what matters. So can you.

WHEN PASSION PAYS: He may be a rock-star millionaire with three platinum albums, but Jack Johnson still makes time for what matters. So can you.According to our adventure-minded sources, it's fairly simple: The happiest people find ways to make their professions and their passions intersect. They give the same full-throttle commitment to their work as they do to their play, applying balance as they goÔÇöand getting the ride of their lives.

Wish you could do that, too? Want a life filled with thrills, challenges, and good works? Want to do all this and still pay the mortgage, nurture a family, and have a life fueled by participation? It's within your grasp, and we're here to help. On the pages ahead, you'll find ideas to help you reach toward the life you've imagined, and you'll hear from a cast of inspiring people who have pioneered the way, from surfer/songwriter/supernova Jack Johnson to a mountain-biking brewmaster, not to mention a former location scout for celeb photographers who chucked it all to scour Asia as an importer of the world's finest tea. While their paths and vocations span a broad landscape of possibilities, our role models all have something in common: a yen for a more organic and inspired life, plus the creativity and drive to make their dreams materialize. If that's not enough, we've also got a roundup of the best books, courses, programs, and Web sites, and sage advice from a life coach who's going to urge you not to waste one more day just wishing. “Having it all” isn't just a phrase for fairy tales. It's the most important thing you can do to make your worldÔÇöand the world at largeÔÇöthe best possible place to live.

Jack Johnson, Rock Supernova

More than 5,000┬á cold, wet fans stood in the April mud and rainy darkness at the Beale Street Music Festival, on the banks of the Mississippi River in Memphis, chanting, “We want Jack! We want Jack!” You'd think this would be manna to a folk-rock god, but, sitting on a sofa in a backstage trailer, Jack Johnson had other ideas. “Music is a secondary thing in my life,” he told me.

Timm Smith, Product Developer

Job Description: Employed by W.L. Gore & Associates, the Newark, DelawareÔÇôbased product-development company that invented Gore-Tex in 1969, Smith works with teams that invent materials used in products like the Gore-Tex Soft Shell.

Why This Work Rules: Hiking in the German Alps and ice-climbing in Ouray, Colorado, are both on-the-clock activities when testing prototypes. “It's a ÔÇśwork is part of life is part of work' kind of thing,” says Smith. “I've found a good fit.”

Turning Point: While earning his chemical- engineering degree from the University of Delaware, Smith worked for a year as a process engineer and hated it. In 2001, at a University of Delaware job fair, he met a Gore recruiter who sold him on the company's unusual modus operandi: a less hierarchical structure and plenty of creative freedom to stretch his designer's mind.

The Balanced Life: Smith averages a 50-hour workweek, but 10 percent of that is company-sanctioned “dabble time” spent dreaming up new projects. When he's not working, he's hiking, mountain-biking, running, and hanging with his wife, Rachel, and their two German shepherd mixes.

Reality Check: Bouncing between Gore's offices in Europe, Asia, and the U.S. means at least one week away from Rachel every two months.

The Bottom Line: Product-development salaries in apparel and footwear range from $50,000 to $140,000. A survey of product-design jobs can be found at the 's website. Engineering degrees aren't mandatory, but they can help. Reputable schools (where Gore in particular does its recruiting) include Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI), Lehigh University, Virginia Tech, Penn State, the University of Utah, and the University of Delaware. Postgrads can investigate professional development courses in product design like the one at .

Jessie Stone, Health-Clinic Director

Job Description: Professional rodeo kayaker and M.D. who directs Soft Power Health, a two-person nonprofit organization she founded in 2004, which operates a kayaking camp for inner-city kids in NYC and a malaria clinicÔÇölocated on the White Nile in rural UgandaÔÇöthat provides education, prevention, and treatment.

Why This Work Rules: It sure ain't the money. But when Stone first arrived in Kyabirwa, few of the thousand or so villagers knew how malaria was transmitted, let alone prevented. Now mosquito nets cover at least 1,000 beds in villages around the region, and infant mortality is expected to decline. “People are so grateful,” says Stone. “The outpouring of emotion is so intense, it's almost more than I can handle, and it has forever changed my perspective on things. I feel incredibly lucky.” Plus, after work she gets to kayak the Class V White Nile.

Turning Point: After graduating from New York Medical College in 1999, Stone decided to forgo residency and pursue a whitewater-kayaking career. On a 2003 trip to Uganda, she treated two fellow kayakers for malaria. “That made me look around and think, My God, does anyone here sleep under a mosquito net?” Stone says. A year later, she started the education program and laid plans for the clinic.

The Balanced Life: The slow pace of life in Africa offsets the stress of the U.S. “When I go to Uganda,” says Stone, who has spent five months there this year already, “I take in the scenery, chat up the villagers, and write lettersÔÇöthe things you'd never have time for in New York.” In the U.S., Stone prioritizes playing tennis with her dad and going to the theater when she's not orchestrating fundraisers or off paddling.

Reality Check: Stone has no permanent address. Stateside, she usually stays with her parents in Westchester County, New York; in Uganda, home is a banda, a hut at the Nile River Explorer's Camp.

The Bottom Line: Health-care salaries overseas vary wildly, depending on your situation. Because Stone's overhead costs eat up donations, her income is just $18,000 a year. Want to take her path? Go to a med school like the , in Los Angeles, which focuses on helping the underserved. Get a health-care job with groups like , the , , or . provides housing, airfare, and a stipend for clinic volunteersÔÇöno medical experience required.

Holly Morris, ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° Filmmaker

Job Description: Writer/director/host/executive producer of ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° Divas, a documentary-style travel show on PBS that profiles innovative women around the world. Morris is also the host of Outdoor Investigations, a series that takes an up-close look at North American environmental issues and airs on the Outdoor Life Network.

Why This Work Rules: Good adventureÔÇöwhat's not to love about traveling the globe making documentaries on “divas”? “These women don't wait for their ships to come in; they row out to meet them,” says Morris. Her recent experiences include filming the beauty parlors of Iran and documenting Cuba's female rappers. The best part? No two days are the same.

Turning Point: After three years in Seattle as the editorial director at Seal Press, which is now an imprint of Avalon Publishing Group, Morris was inspired by a book series called Adventura, which covered women, travel, and international politics. Though she had no film experience, at 32 she quit her job, scrambled for funding, and spent ten days in Cuba shooting her ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° Divas pilot. PBS picked it up and commissioned the series in 2000. “You don't have to be an 18-year-old with a backpack in order to have epiphanies that lead to life changes,” says Morris.

The Balanced Life: In Morris's case, balance means splitting her time between Seattle, Brooklyn, and the rest of the world. Wherever she is, life off the job is similar to life on the jobÔÇöminus the cameras. “I travel, fish, read, and try to meet interesting people,” she says.

Reality Check: “There are moments when you're puking your guts out in the middle of nowhere when you think, Why do I do this?” Morris says.

The Bottom Line: As the boss, Morris pays herself last, bringing in anywhere from $15,000 to more than $100,000 per year (salary ranges in the documentary-film biz are notoriously variable). For more information about what's going on in the filmmaking world, or to find a group in your neck of the woods, consult the Association of or go to a local film festival. For more from Morris, check out and read her ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° Divas: Searching the Globe for a New Kind of Heroine, coming out in October from Villard ($24).

Lincoln Else, Climbing Ranger

Job Description: As the only full-time climbing ranger in Yosemite, Else patrols the park's world-class climbing routes, leads rescues, and keeps peace between park brass and rock jocks.

Why This Work Rules: “Helping to save the life of someone who's gotten themselves stuck in the wilderness is rewarding,” says Else. So is spending a few days a week climbing one of Yosemite's thousands of routesÔÇöbecause part of his job is to know what shape they're in. “I get paid by U.S. tax dollars to go climbing,” he says. “It's a hell of a lot of fun.”

Turning Point: An avid climber who spent weekends honing his skills in places like New York's Shawangunks while earning a philosophy degree from Yale, Else bolted for Yosemite upon graduating in 1999. What began as an internship eventually became a careerÔÇöhe landed a permanent position after a four-month volunteer stint in Yosemite's Wilderness Department, issuing permits and patrolling the backcountry. “My job is fun and exciting,” he says, “but the real reason I stay is because I believe in the mission of the National Park Service.”

The Balanced Life: Since the climbing season lasts only six months, Else spends half his time engaged in other part-time work. He's been a paralegal for a defense attorney in Palo Alto, California; a lobbyist for the Natural Resources Defense Council, in Washington, D.C.; and a documentary filmmaker.

Reality Check: Sometimes a search and rescue turns into a recoveryÔÇöthe park averages one or two climbing fatalities each year. Another issue is the notorious tension between park rangers and the climbing community. “We're constantly faced with the challenge of balancing preservation with enjoyment,” says Else.

The Bottom Line: Park Service jobs won't make you rich: Else, for one, takes home $15,000 to $20,000 each May-through- October season. But the office space is priceless. Want in? Get outsideÔÇöa lot. Take courses from Grand Teton National ParkÔÇôbased or from the . Check out the , the , or . If you love climbing, aim for work at Grand Teton, Yosemite, Denali, Mount Rainier, or Joshua Tree, where it's a major draw.

Jim Cantore, Broadcast Meteorologist

Job Description: At The Weather Channel, Cantore hosts Storm Stories, regularly anchors the prime-time Evening Edition, and is TWC's resident “storm tracker,” reporting live from the field when Ma Nature's at her gnarliest.

Why This Work Rules: Even though he's often seeing the country at its meteorological worst, blitzing after blizzards, hurricanes, and tornadoes remains a thrill. “I couldn't sleep as a kid when snow was forecasted,” says Cantore, who grew up skiing in White River Junction, Vermont. “I'd run out there to play as soon as it started, even at 3 a.m. Now chasing storms is my livelihood.” Bonus: After he covers a blizzard in Colorado, he's right there for the best powder.

Turning Point: Cantore's dad urged him to follow his storm-related passion by becoming a meteorologist. But it wasn't until Cantore nailed an on-camera report in his junior year in the meteorology program at Vermont's Lyndon State College that he realized broadcast TV was his true calling. After graduating in 1986, he sent his tapes to TV stations all over the country. The Weather Channel was his first interview.

The Balanced Life: Cantore spends about a third of the year reporting for TWC, but when he's not, life is about family, being outside, and teaching a broadcast-meteorology class as a visiting instructor at Lyndon State. In the summer, he steals weekends at his cabin in northern Georgia to hike, run, and garden. He and his wife, Tamra, who was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease eight years ago, also raise funds for research on Parkinson's and fragile X syndrome, a genetically inherited mental impairment that afflicts his two children, Benjamin, 10, and Christina, 12.

Reality Check: With two special-needs kids, Cantore's away more than he'd like to be. “The biggest storm I've ever covered is my life,” he says.

The Bottom Line: Broadcast-meteorologist salaries run the gamut, from $20,000 for an entry-level job in a small market on up to $1 million for top pros at the major networks. Weatherheads should read The USA Today Weather Book (Vintage, $21), by Jack Williams, and storm enthusiasts can join the National Weather Service's . Getting serious? Consider a degree in broadcast meteorology from top programs like those at or .

Rogan Lechthaler, Sous-Chef

Job Description: As second in command at Warren, Vermont's Pitcher Inn, a historic 11-room country lodge at the foot of Sugarbush Resort, Lechthaler is responsible for food prep, inventory, menu planning, cooking, and creating new dishes.

Why This Work Rules: Lechthaler's quandary was finding a high-end position that let him satisfy two disparate passions: gourmet cooking and ripping pow. (“I basically grew up with skis on,” says the Vermont native.) At the Inn, he found his answer. His shifts start at 1 p.m., after leisurely mornings spent skiing or jogging. At any given time, the elegant menu features several of Lechthaler's own culinary concoctions, like duck-and-prosciutto ravioli or striped bass with thinly sliced fennel. He's generally home by midnight.

Turning Point: Lechthaler paid his dues as a breakfast chef in Boston (wake-up time: 4:30 a.m.) before moving to the evening shift, which he loves. But it wasn't until he landed a sous job at Boston's MistralÔÇöa hot spot for foodiesÔÇöthat he realized swankiness does not mean happiness when home is a four-hour drive from his favorite slopes.

The Balanced Life: The hours are longÔÇö50 to 60 for most five-day workweeksÔÇöbut Lechthaler takes full advantage of his free mornings. As a volunteer ambassador at Sugarbush, a post that involves meet-and-greets at the resort, he spends many winter hours schussing and schmoozing. He also indulges in philanthropic pig roasts. In 2003 his swine-on-a-spit approach to fundraising netted $3,000 for the Food Project, a Boston-area nonprofit; this year, he plans to organize road-race/pig-roast charity events.

Reality Check: In a profession that's notorious for breeding workaholics, burnout is always a threat. “You hear about chefs putting in 80-hour workweeks,” he says. “But I'll be the first to say, ÔÇśYou know what? Today is a powder day.' You have to do that stuff to keep your vitality in the kitchen.”

The Bottom Line: Sous-chefs make $30,000 to $45,000 a year. Interested? Land a kitchen job and work your way up, says Lechthaler, who bypassed cooking school (though many of his colleagues took that path). Look for openings at ; for a primer, read the book by Andrew Dornenburg and Karen Page.

Kelly Streeter, Structural Engineer

Job Description: Climber/consultant for Ithaca-based Vertical Access, a 13-year-old company whose seven employees use rock-climbing skills and roped rigging systems to scale and inspect architectural structures across the nationÔÇöfrom historic statehouse domes and churches to buttresses and bridges.

Why This Work Rules: It's hard to beat playing Spider-Man in New York City, rappelling down the stainless-steel spire of the Chrysler Building, carrying a water hose to test for leaks, or tiptoeing around the towers of St. Patrick's Cathedral to check their condition. To carry out surveys, Streeter and fellow techniciansÔÇöamong them a historic preservationist and a masonry expertÔÇöconstruct a fail-safe system of ropes that allow them to clip in, climb up, and get close to beautiful landmarks. Working hands-free, they investigate and meticulously map a building's condition, entering data into a handheld computer while hovering hundreds of feet above the ground. “We get to see these amazing parts of buildings that no one else sees up close,” Streeter says.

Turning Point: Streeter taught rock climbing while she was working toward her bachelor's degree at Cornell University, first meeting Vertical Access employees at the school's climbing wall, where the company holds training sessions. After she graduated, she took a job at an engineering firm designing buildingsÔÇöand did freelance work with Vertical Access “every chance I got,” she says. Finally, at age 26, she realized her true love was for old structuresÔÇönot new ones. She got a master's degree in structural engineering from the University of Colorado at Boulder, joined Vertical Access, and hasn't looked back.

The Balanced Life: Streeter works long hours, but she gets to file paperwork from home and enjoys downtime between jobsÔÇöan important perk, since she has an 18-month-old daughter and another child on the way. She feeds her passion for old buildings by volunteering on a local historic-preservation board. To get away from it all, she and her husband, a software programmer and recreational pilot, fly in their four-seat Piper Cherokee to eastern-seaboard hideaways and camp out.

Reality Check: “The work can be intensive and tough,” Streeter says. On one job, she dangled beneath the 90-foot-high arches of New York City's Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine for more than three hours while installing crack gauges with a hammer drill.

The Bottom Line: Structural engineers typically make $45,000 to $75,000 a year. For more info on Streeter's work, check out or the . The provides a broader overview of engineering jobs and more.

Sebastian Beckwith, Tea Purveyor

Job Description: As the founder and co-owner of In Pursuit of Tea, a three-person tea-importing business, Beckwith travels the globe, finding, buying, and selling the world's rare and exotic teas.

Why This Work Rules: In a word: variety. “I can be sitting with farmers in some dusty back-roads part of Darjeeling one day and tasting tea at a five-star restaurant a few days later,” says Beckwith. He also educates people about teaÔÇöcustomers, doctors at Columbia University's annual botanical medicine conference (where he guest-lectures), or Bhutanese government officials trying to help farmers develop cash crops.

Turning Point: Since Beckwith dropped out of UC Boulder in 1984, he's been an art handler in NYC and a freelance location scout for photographers such as Peter Lindbergh and Annie Leibovitz. In 1995, he started guiding monthlong treks to India, Nepal, and Bhutan for San FranciscoÔÇôbased outfitter Geographic Expeditions. That, and traveling in Asia on his own, ignited a connoisseur's passion for teaÔÇöa staple of Asian culture. Beckwith saw a market for high-quality rare teas in the U.S. and launched the company with his friend Alexander Scott in 1999.

The Balanced Life: Beckwith visits Asia about three months a year, touring plantations and helping ensure his suppliers are using good environmental practices. In Brooklyn, he's either working at the company office, dining out with friends like climber and filmmaker David Breashears, or networking with chefs who might serve his tea in their restaurants. Weekends find him sequestered at his off-the-grid cabin in northwestern Connecticut.

Reality Check: Importing agricultural products has been stressful since 9/11, which brought about tougher FDA regulations. Beckwith often spends up to 70 hours a week working (and sometimes sleeping) at the company office. “Sometimes I'm up at 7 a.m. and still working at midnight because that's when a chef has some time,” he says.

The Bottom Line: Running your own import business won't make you rich overnight, but established tea peddlers can earn between $60,000 and $80,000 a year. Newbies with big ideas can glean guidance from by Carl A. Nelson. Or visit , a clearinghouse of information for beginners and professionals.

Kristen Ulmer, Ski Guru

Job Description: A former big-mountain freeskier and film star, Ulmer founded Ski to Live in 2003ÔÇöthe first-ever spirituality-based sports clinic for alpine skiers and snowboarders. Through STL, Ulmer and her Buddhist mentor Genpo Roshi, 61, hold multi-day retreats focusing on yoga, skiing, and personal growth.

Why This Work Rules: She gets paid to ski (though not nearly as much as when she was making six figures as a pro) and practice yoga, but Ulmer also gets to give something back. “People usually come to the clinics to learn how to ski better,” she says, “but they leave having had their minds blown open.”

Turning Point: After 15 years making films and tearing up the freeskier circuit, Ulmer outgrew the extreme-athlete limelight. In 2002, she attended a personal-growth workshop in Sundance, Utah, and then went to the Burning Man festival, in Nevada, where she explored her creative side through performance art. “I realized at Burning Man that I wasn't living an authentic life. As soon as I got home, I wrote a resignation letter to my sponsors and decided to focus all my energy on Ski to Live,” says Ulmer. “It was a complete 180.”

The Balanced Life: Winter finds Ulmer skiing in Utah's Wasatch Mountains, practicing yoga, and hosting STL. In the summer, she rock-climbs and kiteboards. Ulmer feeds her philanthropic streak by raising money to help cancer survivors attend STL and taking underprivileged teens climbing and skiing in Utah.

Reality Check: Known for taking big risks in perilous places, Ulmer says STL is the biggest leap she's taken yet. “I have so much of my heart invested in this and want so much for it to be successful,” she says. “If it blows up tomorrow, I'll be devastated.”

The Bottom Line: The rewards of becoming a guruÔÇöski or otherwiseÔÇöare more spiritual than material (STL earns Ulmer $15,000 to $20,000 a year). Books like by Eckhart Tolle, and by Paul Edwards, Sarah Edwards, and Peter Economy, can help you turn your creativity into your livelihood.

Chris “Gunny” Gunnarson, Terrain-Park Designer

Job Description: Founder and president of Snow Park Technologies, a 17-person company that designs high-quality ski-and-snowboard terrain parks for resorts and events like the X Games.

Why This Work Rules: The daily grind is pretty glorious. “I don't ever have to wear a tie,” Gunnarson says. “I don't have to shave, and I get to surf, skate, and snowboard as a major part of my work.” He also jet-sets across the country, building parks and surveying and maintaining others designed by his crew. His own stature as an industry celeb has found him riding with the likes of Justin Timberlake, Emilio Estevez, and Seal.

Turning Point: Growing up at the beaches and skate parks of Southern California, Gunnarson first tried snowboarding on his 13th birthday at Mountain High, a small resort in SoCal's San Gabriel Mountains. “That first weekend, I said, 'I want to do this for the rest of my life.' ” Gunnarson recalls. His second job out of high school (his first was in a restaurant) was a ski-patrolling gig at Snow Summit, in Big Bear Lake, California, in 1992. By the 1994ÔÇô95 season, he was competing as a pro snowboarder and pushing Snow Summit to improve its parkÔÇöand thereby reduce the growing number of injuriesÔÇöby making the jumps, ramps, and berms flow better through one continuous run. Snow Summit management thought that was a good idea; they put him in charge, and the X Games launched Winter X at the mountain the next year.

The Balanced Life: From December to April, Gunnarson's life is all about snow. And when it melts? He stays busy drawing up blueprints for next season's projects, improving terrain-sculpting hardware and equipment, and speaking (gratis) at conferences about snow-park operations. He also finds time for his nine-handicap golf game, rides on his Yamaha 426 dirt bike, surfing, and outings with his wife of six years.

Reality Check: As Gunnarson has become a bigger name, his managerial duties have carved away some playtime. “Sometimes it's dumping outside and I've got to return all these calls,” he says. “But sometimes you do have to just say, 'Screw it,' and go anyway.”

The Bottom Line: Park-designer salaries start out around $30,000, but those with top skills like Gunnarson can clear $100,000 annually. Other winter-resort work will range from minimum wage for, say, an entry-level lift-loader, up to the low six figures, for exec positions at larger resorts. is a clearinghouse for on-mountain jobs, and lists openings at major U.S. resorts. Also, most resort areas host job fairs in October to hire staff for their upcoming season.

Jimmy Lizama, Cycling Angel

Job Description: Community activist, bike messenger, and founder of the Bicycle Kitchen, a four-year-old, cooperatively run nonprofit bike-repair shop in East Hollywood, where urban cyclists, bike messengers, schoolkids, and others hang out, swap advice, and learn how to fix their rides.

Why This Work Rules: “Everybody gets empowered,” says Lizama, a galvanizing force in the L.A. bike scene. At the Kitchen, he spreads the biking gospel, organizes repair classes, and gives bikes to needy kids.

Turning Point: In 1999, Lizama woke up too late to catch the bus to his art-gallery job, so he grabbed his rusting Huffy, pedaled the five miles, and passed three buses en route. Instantly bike-addicted, he left the gallery, became a bike messenger, and, in 2001, transformed the kitchen of an empty apartment near his own, in the sustainable-living community L.A. Eco-Village, into a bike-repair spot. People flocked in, including Lizama's soon-to-be Kitchen partner, Ben Guzman. To ease crowding, the Kitchen relocated this year to its current storefront.

The Balanced Life: The Kitchen is open at least seven hours daily from Saturday through Monday, and from 6:30 p.m. to 9:30 p.m. Tuesday through Thursday. That still gives Lizama time for messenger work, vying in bike-messenger competitions, and enjoying the Midnight Ridazz, a mass nighttime fun ride through Los Angeles. He's also devoted to capoeira, a Brazilian martial art.

Reality Check: “There's sacrifice involved,” Lizama says. “I dump money into the Kitchen, and it doesn't give me money back.”

The Bottom Line: Directors at established nonprofits can make $40,000-plus a year, but at the KitchenÔÇöwhere donations barely cover expensesÔÇöLizama's salary is zero. To survive, he brings in $32,000 to $60,000 a year as a messenger. Still think his gig sounds cool? Check out and work at a nonprofit that inspires you. “The minute you apply your skills to a kid or someone who can't afford to pay you and you love it,” says Lizama, “you'll know you're in it for the right reasons.”

Rob Spencer, Brew Meister

Job Description: Founder of Mobius Beer, the company that produces and distributes the first “energy-infused” microbrew, containing taurine, ginseng, caffeine, and vitamin B1.

Why This Work Rules: Producing 120,000 bottles of beer a month with only two full-time staffers, Spencer gets to run his own show, from grassroots marketing at local sailing races to making in-person sales pitches at bars. His Mobius-related travels have put more than 50,000 miles on his Dodge Sprinter van as he's promoted his product up and down the East Coast with copilot Briscoe, his Australian cattle dog. Along the way, he fly-fishes and mountain-bikes. Back home, he also plays rugby. “I try to sell some beer,” he says, “and when it's over, I take my mountain bike out, and my dog and I go for a ride.”

Turning Point: Burned out after a series of jobs he'd taken since 1989, Spencer began working as a bartender at a pub in Charleston in 2003, during which time he got a taste of the Red BullÔÇôandÔÇôvodka rage. Fun, sure, but he hated the syrupy-sweet taste. After conducting some self-education, soliciting the input of his sister (a chemical engineer), investing a chunk of his life savings, and mentoring with brewers like Pete Slosberg, of the San Antonio, TexasÔÇôbased Pete's Wicked Ale, Spencer served his first commercial mug of Mobius Lager in Charleston in November 2004.

The Balanced Life: “Carpe diem” is corporate philosophy at Mobius. “I work as hard as I can and enjoy it the whole way,” says Spencer. “If I'm not enjoying it, time to do something different.” Spencer pours 10 percent of his profits into the Food and Beverage Insurance Organization, a nonprofit he created to help restaurant workers acquire health insurance. To recharge at home, he beachcombs with Briscoe or rides the trails of Francis Marion National Forest.

Reality Check: Securing distribution is tough. “I can go to a sailing regatta in Key West, have a great time, and everyone loves the beer, but then they ask where they can get it in their area and I tell them they can't,” says Spencer. “In the alcohol industry, the distributors hold all the cards.”

The Bottom Line: Beermakers at startups like Mobius can plan on raking in about $20,000 a year. But that can climb to $100,000 at the most successful microbreweries. Think you're serious? The , in Chicago, is the country's premier brewing academy, offering a two-week survey course or a 12-week international diploma of brewing technology, which includes five weeks at its sister facility in Munich ($2,950 and $13,500, respectively). Does your interest lean more toward handcrafted wine or spirits? Check out , which provides a thorough list of links to resources for making specialty beverages at home.