Steve Nash builds green gyms, runs a charitable foundation, and directs indie films—all while ruling the NBA. Like the nine other iconoclasts we’ve gathered here, he knows that if you want something done right …

Steve Nash

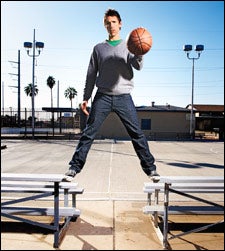

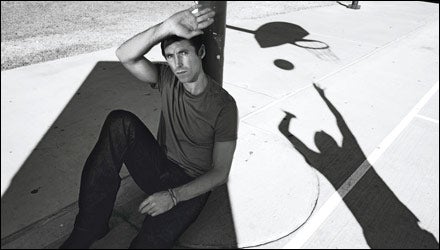

Nash in Phoenix's Grant Park in October

Nash in Phoenix's Grant Park in OctoberPLUS: Do-It-Yourself Tips

╠ř

╠ř

╠ř

╠ř

The Instigator

Phoenix Sun, entrepreneur, filmmaker, do-gooder

It’s late October, and I’m standing in the shade of a spindly palm tree in Phoenix’s Grant Park. One of the veterans from the American Legion post across the street wants to know who we’re taking pictures of.

“That’s Steve Nash, from the Suns,” I tell him.

“Stevenash? I love that guy!

I can’t believe this. Stevenash!” The wrinkled old guy shuffles across the street and snakes through the neighborhood kids arrayed around the Phoenix Suns’ point guard, asking for autographs. So far, the Victoria, B.C.┬ľraised Nash has dished out more than 60 signatures and posed for more cell-phone snapshots than portraits by our photographer, Nigel Parry.

When your day job is marshal┬şling the offense for an NBA contender, it would be easy to retreat behind the people who run your charity and ink your endorsement deals. But not Nash, who has a crazy number of balls in the air: sports idol, husband, father, soccer fanatic, president of a charitable foundation, filmmaker, fitness addict, and, most recently, co-founder of the Steve Nash Sports Club, a $5 million Vancouver gym that opened in 2007, with up to 12 more locations planned for B.C.

“I’ve known him since we were 11,” says Jenny Miller, executive director of the Steve Nash Foundation, “and Steve has always been an instigator. As movement-oriented as he ison the court, that’s Steve off the court. You could say he has a kinetic heart.”

You could, but Nash’s explanation is simpler. “My gifts as a basketball player are my commitment, perseverance, and hard work,” he tells me. If you’ve watched him play, you know that’s an understatement. More wisdom from our humble hero:

1. There’s time in the day for everything. A point guard’s job is to “create”┬Śto feed the ball into scoring opportunities and, if one plan fails, immediately try something else. Nash takes this concept to the extreme. He bites off more than most citizens, much less pro athletes┬Śand until this year, he’s done it all by himself. His secret? Using every spare moment.

“I finally hired some people,” he acknowledges, “but I use my time to do the things I love. There’s time in the car to make calls and time on the plane to work. I’m always on the phone or Skype or e-mailing about the foundation or films, things we’re doing in the gym. I multitask.”He pauses. “I just think those things are a lot more fun than sitting around watching TV.”

2. Make everyone around you better. In 2006, Nash became the third guard in NBA history to win back-to-back league MVP awards, and he did it while placing 29th in scoring┬Śbut first in assists.?Always the instigator, he brought high-octane play back to the NBA, stampeding down the court, reading the situation, and making ridiculous passes┬Śoften behind his back or between an opponent’s legs, but always for the sake of setting up his teammates.

That year, Time put him on its list of 100 “People Who Shape Our World,” in which Charles Barkley wrote of the Suns guard, “What has he taught us? It pays to be selfless. You can be content just to make the players around you better.”

Off the court, it’s no different. Consider Nash’s foundation, which funds early-childhoodeducation in Arizona, builds pediatric-cardiology wards in his wife’s native Paraguay, and is at work on a youth center in war-torn Uganda. During the season, Nash spends at least ten hours a week on day-to-day operations, and in 2008 the group won the Steve?Patterson Award for Excellence in Sports Philanthropy.

And he doesn’t stop there. In 2007, Nash persuaded his friend Yao Ming to help him organizea game in Beijing that raised $2.5 million for AIDS orphans and other causes, and last off-season he started a benefit soccer game in New York with American player Claudio Reyna.

3. Marry your work and your passion. Last year the Suns organization announced that it would start converting Phoenix’s US Airways Center into, fittingly, a solar-powered facility in 2009. Who had come to the team with the idea two years earlier? Yeah, that’s who.

He again had the earth in mind when he joined with Mark Mastrov, creator of 24-HourFitness, to bring a state-of-the-art gym to his home province.

“I’ve spent half my life in gyms,” he says. “I love for people to be healthy, whether it’s mentally, physically, or emotionally.”

The 38,500-square-foot Steve Nash Sports Club follows LEED principles, using low-voltage lighting, bamboo floors and lockers, rugs made from old shoelaces, and recycled-rubber workout surfaces. In keeping with his holistic-health philosophy, the club combines weights and yoga, cycling with Pilates. In the future, the gym will up the eco-ante withnew energy systems as they become available.

“As we go on, we’d love for the cardio equipment to generate energy,”?says Nash, “to have people provide the energy for their gym with their energy.”

4. Make workouts fun and they won’t be work. Nash and his family spend their summers in New York’s Tribeca neighborhood, where they don’t drive a car. Instead, to get to his workouts at Chelsea Piers, Nash makes the three-mile commute up the West Side Highway on his skateboard. It’s his way of being a normal guy, having fun, and getting an aerobic workout.

At the gym, his routine includes 15 or 20 minutes of shooting, 20 to 30 minutes of weight lifting, more shooting, and then the skate home, where he might jump rope and run stairs for more cardio. Again, he makes it work by killing multiple birds with one stone.

“Even when I play soccer in the summer, I’m consciously and subconsciously thinking about how I’m moving, making sure that I’m using the right muscles, using the right sequences, leading from the center ┬ů”

So hold on. While playing soccer for fun in July, he analyzes “sequences”?

“I think about it in the moments I can, and hopefully those moments allow it to become second nature in the moments that you’re concentrating on something else.”

5. Follow your bliss. When I ask Nash who inspires him today, he cites Barack Obama and filmmakers Paul Thomas Anderson and the Coen brothers. He says he’s dead serious about directing movies someday, and he’s already started a production company with his cousin Ezra Holland, a music-video director. The pair have created Web shorts for Nike, like last year’s “The Sixty Million Dollar Man,” to promote the recycled-leather Trash Talk shoe. In it, Nash does a Lee Majors impression as he dives for a loose ball, cracks into pieces, and has to be put back together as “the world’s first recycled man.” This fall he made some ads for VitaminWater that show he’s not afraid to make fun of himself; in one, he barges into a crowded office and announces, “Excuse me. While I’m here, does anyone need an autograph?”

This year, Nash will put his talents up alongside those of folks like Spike Lee for 30/30, ESPN’s 30th-anniversary series of one-hour films on athletes from the past 30 years. Nash’s contribution will tell the story of Canadian national hero Terry Fox, a 21-year-old cancer victim who in 1980 set off to run across the country with a prosthetic leg, completing 143 marathons in 143 days before tumors in his lungs stopped his effort.

“I was six,” Nash says, “and I remember every day of that summer, waking up and turning on the TV to find out where Terry was. He picked us all up.”

Nash’s documentary, which will air in April 2010, should give another clue to the origins of what drives him. “I think there’s an absolutely direct correlation between me wanting to help people and the fact that I had someone like Terry Fox to look up to as a kid.”

The Trailblazer

Founder, Gunnison Trails

In the 1980s, the lands southwest of Gunnison, Colorado, weren’t being used for anything except party spots and dumping grounds for furniture and appliances. Back then, the BLM policy was simply “There will be no new trails.” No explanation. So we just started going out and building trails. We’d push one of the braided, very faint cow trails in, do a little work with a shovel. There weren’t any laws on the books that said you couldn’t. It took us seven years of cleanup days before we got on top of the trash. A new trail or two was popping up every year.

The last of the pirate trails got built in the late nineties, when we realized the livestock trails we were “improving” were unsustainable. So my thought was, Let’s put some high-quality trails that drain properly on the ground and get rid of the rest. That’s when I started Gunnison Trails, in August 2006. I just chose a name and registered it as a nonprofit online.

Still, you walk into the Forest Service and tell them you’d like to propose a new singletrack, like our most ambitious, a trail between Crested Butte and Gunnison, and they look at you like you’re Looney Tunes. But you keep going back. Now our district ranger knows my name.

There are wildlife and route-density issues, of course. So you pack a meeting room with 50 passionate trail users and find common ground with the land managers, county commissioners, etc. Sage grouse brood rearing is a springtime activity? No problem; we can close the trails during the spring. To make it happen, I have to sell it locally as an economic driver, even though overcrowding is the last thing I want to have happen.

All 30 miles of trails we’ve built so far have been made by a core group of about 25 volunteers. I’m more passionate about trail advocacy than racing mountain bikes. Competing in Leadville against an icon like Lance Armstrong is a special experience, no doubt, but winning is just a cherry on top of the training I was doing anyway. And sure, I’m a little bit selfish in that I ride all the trails we build. But they’re not just Dave’s trails. We built them for theentire community.

The Builders

Principals, Treehouse Workshop

PETE NELSON: In high school, I found a big hardwood on the edge of a farmer’s field, one of those big oaks that went up about 30 feet and branched out. It was the ideal place to build something substantial, and the image must have stayed with me.

JAKE JACOB: Growing up in rural New York, I climbed trees a lot, but we didn’t really have treehouses.

PN: Jake was on the board of directors at the Timber Framers Guild, a nonprofit dedicated to the art of timber framing, so I contacted him about forming a treehouse association. He said, “I’d rather talk about starting a company.” I was raising a family and needed to know there was a living to be made. But we stayed in contact, and in 1997 we launched the Treehouse Workshop Inc.

JJ: The way I thought of it is, If we can afford to put a little ad in The New Yorker, you know, one of those ads that says “Buy Irish cats,” we might succeed. We didn’t have a proper business plan, but here we are 12 years later, with over 100 structures in 32 states and nine countries.

PN: We get Christmas cards from people every year who just love their treehouses.

JJ: Our bread and butter are structures for adults, and they’re more like an addition to your home—escape pods for baby boomers. At IslandWood, a 255-acre environmental learning center on Bainbridge Island, we built a treehouse that serves as a classroom. It needed to be 100 percent supported by this one tree, and it’s got a very steep steeplejack-style roof, with 22-foot-long rafters. To minimize our impact, we had to use block-and-tackle systems, serious rigging in the trees.

PN: It took a small crew of carpenters over a month to build a treehouse on Cape Cod. That one mimicked the old shingle houses, right on the water, in a great oak tree.

JJ: Safety is paramount. You can’t just start nailing two-by-sixes. If there’s gonna be a conflict between the tree and a structure built in it, typically the tree wins. So we work with arborists and structural engineers to come up with connection systems, which are custom-made at machine shops.

PN: What draws many people in is the tree itself. It’s nature grabbing us.

The Constructeur

Founder, Sweetpea Bicycles

The Inventors

When it comes to developing plug-in electric cars, the Big Three rank well behind any three shade-tree mechanics. These are our favorites.A battery-powered replica of a ’32 Ford Highboy

Ed Matula

Redondo Beach, California

Tom Gamso

Cape Coral, Florida

One wheel in back means motorcycle laws and insurance rates apply

A recumbent bike with electric assist

Brian Sauer

Parma, Ohio

Do your favorite woman a favor: Buy her a bike made just for her. Like the custom ones from Portland, Oregon’s Ramsland. After years of seeing women on ill-fitting rides, the former bike messenger took a frame-building course and started her own company. Here’s how she builds a Sweetpea.

1. Racks

It’s easier to design all-year riding—rack, mounts, fenders, and such—into a bike at the beginning. In other parts of the country, people save their nice bike for weekend rides. It’s the opposite in Portland. I make the bike that’s your favorite pair of jeans.

2. Components

A lot of men are just looking for somebody to build their preconceived dream bike. Many of my female customers are happy for me to help them through the parts decisions. Like the Chris King headset. Yes, that’s fancy. But at the same time, it’s going to last forever. She’ll be able to will it to her grandchild.

3. Top & Seat Tubes

Women have more to gain from the complex art of bike fit. If it’s done right, she’s going to know that her bike suits her. It’s going to be functional in ways that store bikes aren’t. The joy is in exploring the finer grain, learning to turn a woman’s dreams into metal.

4. Logo, Colors

I chose “Sweetpea,” a term of endearment, because if you make a bike right, it’s something you can love. We’re making personal artifacts. Understanding people’s stories is how I make the bike meaningful.

5. Lugs

I make all the welds and cuts by hand and use files to shape the miters. You can understand the process at the human level. There’s no automation to building a frame. Everything gets considered, measured, touched, retouched.

6. Wheel Size

One of the ways I help tweak my bikes’ feel is by changing the wheel size. Major bike manufacturers build bikes around wheel sizes. I?build the bike around a woman, using whatever size fits her best.

The Food Fighter

CEO, Growing Power

I was raised on a small farm in Bethesda, Maryland. We were poor, but we always shared what we grew.

I left home at 18 and after college ended up playing pro basketball in Belgium. During my free time, I’d drive out to the country. They were farming like we did, taking care of the land. Seeing them reignited a passion.

When I got back to the States, I started growing and marketing my own food in Milwaukee, trucking stuff in, going from store to store, going to the farmers’ market. My kids ran a roadside stand. At the time, I was working for Procter and Gamble, because I wasn’t making enough on the farm to send my kids through school.

Then in 1993 I found this 19th-century plot—the last remaining farm in the city—with a for sale sign. Something in me said, I need to get this place. So I decided I was going to run it as a for-profit and hire kids from the neighborhood. Restore the greenhouses. Teach them about where their food comes from. About two years in, I was asked to help 25 inner-city Milwaukee kids grow an organic garden. They really surprised me, and that kind of sealed it.

So we’ve grown from just me volunteering with those kids in 1995 to an organization that now has six farms and 35 employees. I’ve gotta have my hands in the soil every day. I’m still the main farmer. We have 20,000 pots in our greenhouses, and I plant every one.

We deliver to restaurants, schools, institutions. We have a retail store and belong to a co-op I started with four other farmers. We do a CSA-type market basket, with four different boxes of food that we can drop into any community in Chicago and throughout Wisconsin.

Nothing at Growing Power is new. People have been growing food inside cities forever. We have to grow farmers so we can grow healthy people and sustainable communities.

The Enabler

Co-founder, Paradox Sports

My brother was paralyzed from the waist down in a 1991 bridge-jumping accident, so I started climbing with him. We completed a route called Space, on El Capitan, in 2005. I do public speaking around the world, talking about that climb. Because of my experience with my brother, other disabled people started reaching out to me.

So in January 2007, I flew to Washington, D.C., to meet D.J. Skelton, a captain in the Army and a climber. Skelton had already been working with Disabled Sports USA, a national nonprofit that does sports rehabilitation, including traditional Paralympic sports like track and field, but they didn’t teach climbing. That afternoon we went to a local climbing gym with a bunch of veterans, including single- and double-leg amputees, and a blind guy. D.J. himself was injured in Iraq and has a semi-paralyzed arm and leg, and he’s missing his left eye and part of his skull. Climbing had changed our lives, so why wouldn’t they get into it, too?

That night, I spoke with D.J. about forming an organization that provides climbing and other alternative sports, like whitewater kayaking and surfing, to people with adaptive needs. We called it Paradox Sports. Within a couple of months we had a board of directors, and we were applying for nonprofit status. The fast pace was less because of us and more because these people just wanted to do sports, hang out, laugh, and crack a beer.

We have a program called Gimps on Ice, in Ouray, Colorado. Gimp is a word you can use if you are one, or if you have honorary gimp status—which I have. Anyway, it’s sort of like Stars on Ice, only people are using the adaptive process to ice-climb. My brother, for example, takes six hours to climb a 50-foot sheet of vertical ice. He is totally in love with that process. Next, we want to do an all-gimp ascent of El Cap. Meaning no able-bodied people. Hopefully we’ll have a paraplegic and an amputee or two.

Our group also works on new prosthetics, which started back in the summer of 2006 when Aron Ralston and I climbed the Diamond, the east face of Longs Peak. Aron, of course, is missing his right hand, so Paradox Sports helped create both his ice-climbing and rock-climbing prosthetics. They’re titanium hooks that attach to the end of his prosthetic. We work with a Boulder-based prosthetics company called TRS, owned by Bob Radocy, an amputee himself. They make kayak grips, among other things, and we put them into action.

The paradox is that even after part of someone is lost, the person can still be whole. We all experience fear, hunger, and gravity the same way. We’re all kind of disabledwhen we’re up on a big wall.

The Mountain Maker

Co-founder, Silverton Mountain

I started out staring at a map. I had never been to Silverton, Colorado, but moved there with my wife, Jenny, in October of 1999. There were a few depleted mining claims we liked. We were trying to figure out how to maximize access to the best terrain with a simple rope tow. Originally, we were just gonna buy ten acres and allow people access to the adjacent public lands, but that didn’t work out, so we started thinking bigger. We eventually got 519 acres for the price of a condo at your typical ski resort. Over the eight years it took to get started, I’d say three were spent dealing with permits. County, liquor, land, BLM, lawyers—I didn’t finish the permitting process until 2007. We have just one chairlift, a used one we bought from Mammoth. They wanted $150,000 initially, but the Forest Service gave them a deadline. We got it for $25,000. With only one lift, you have to hike to get to a lot of our terrain. You also need an avalanche beacon, shovel, and probe, but we rent all that stuff. We’ve come a long way. The first year, we had two employees—my wife and I guided. Now, finally, we’re able to enjoy the mountain ourselves.

SILVERTON STACK-UP

10

Acres of land Brill initially bought in the defunct mining town of Gladstone, just outside of Silverton (pop. 500). After ten years of environmental assessments and a new 40-year lease, the ski area now covers 1,819 acres.

8

Semi loads required to haul the lift’s 15 towers, 120 chairs, two miles of cable, pair of terminals, 200-hp motor house, and two 11-foot bull wheels 900 miles from Mammoth to Silverton.

20

Maximum number of skiers per day the BLM allowed Brill his first year of operation.After yearly increases, Silverton can now host 475 backcountry users a day.

thirty

Number of snowboards Brill has beaten to death since 2001.

50

Cars that can fit, double- and triple-parked, in the parking lot, which is ten feet from the lift.

20K

Estimated board-feet of timber felled to clear the lift line. For three and a half months, Brill and one other worker cut down about 75trees a day. The wood sold for $15,000.

52

Helicopter trips required to haul enough concrete to fill the swimming-pool-size hole that Brill’s crew dug by hand to create the top terminal’s foundation.

13,487

Elevation, in feet, of the summit of Silverton Mountain, making it the highest ski area in North America.

1977

Year the International school bus that still houses the ski area’s “ski shop” was built.