December 5, 2001: Climbing teams push on with expeditions despite violence.

Three masked Maoist militiamen, the author’s guides to a guerilla rally in western Nepal.

Three masked Maoist militiamen, the author’s guides to a guerilla rally in western Nepal. Kathmandu-based photojournalist Thomas Laird’s exclusive photograph of the royal funeral pyres blasing on the Aryaghat (steps) of the Pushapati Temple, above the Bagmati River, in central Kathmandu. The shot was taken at 1:00 on the morning of June 3, 28 hours after the massacre. The three pyres are those of Prince Nirajan (far left), younger brother of Crown Prince Dipendra; Queen Aiswarya (center); and King Birendra (far right).

Kathmandu-based photojournalist Thomas Laird’s exclusive photograph of the royal funeral pyres blasing on the Aryaghat (steps) of the Pushapati Temple, above the Bagmati River, in central Kathmandu. The shot was taken at 1:00 on the morning of June 3, 28 hours after the massacre. The three pyres are those of Prince Nirajan (far left), younger brother of Crown Prince Dipendra; Queen Aiswarya (center); and King Birendra (far right). Ascending the trail into the Maoist heartland in the Rolpa Hills beneath a banner advertising the upcoming rally.

Ascending the trail into the Maoist heartland in the Rolpa Hills beneath a banner advertising the upcoming rally. Illustrated Map of Nepal.

Illustrated Map of Nepal. A Maoist militiaman raises his flintlock to salute approaching comrades.

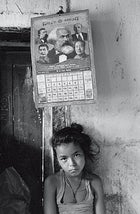

A Maoist militiaman raises his flintlock to salute approaching comrades. Rolpa girl with communist all-stars calender.

Rolpa girl with communist all-stars calender. Garbage-pickers working Durbarmarg. Kathmandu is a monument to foreign-aid rip-offs, say Nepal watchers.

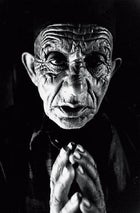

Garbage-pickers working Durbarmarg. Kathmandu is a monument to foreign-aid rip-offs, say Nepal watchers. Seventy-five-year-old Ratibhan Oli fled his town after the Maoists took it over. To them he is a “revisionist,” to the government he is a refugee.

Seventy-five-year-old Ratibhan Oli fled his town after the Maoists took it over. To them he is a “revisionist,” to the government he is a refugee. Happiness for this village woman at the Rolpa rally is a well-packed cannabis pipe and a day of Maoist sloganeering.

Happiness for this village woman at the Rolpa rally is a well-packed cannabis pipe and a day of Maoist sloganeering. Royal Nepalese Army regulars patrol the highway between Kathmandu and Rolpa.

Royal Nepalese Army regulars patrol the highway between Kathmandu and Rolpa. Red Army soldiers en route to the clandestine rally.

Red Army soldiers en route to the clandestine rally. Comrade Strong Man and one of his flunkies.

Comrade Strong Man and one of his flunkies. Maoist commander Sanktimon, aka Comrade Strong Man, declares a shadow government before 10,000 cheering supporters at the rally in Babhang. Moments later, he dragged the author onstage to address the crowd.

Maoist commander Sanktimon, aka Comrade Strong Man, declares a shadow government before 10,000 cheering supporters at the rally in Babhang. Moments later, he dragged the author onstage to address the crowd. A cardboard effigy of Prime Minister Koirla hangs in the streets of Bhalubang in Rolpa district, one of several regions where the Maoist insurgency has taken hold.

A cardboard effigy of Prime Minister Koirla hangs in the streets of Bhalubang in Rolpa district, one of several regions where the Maoist insurgency has taken hold.November 28, 2001: U.S. State Department cautions Americans about travel to Nepal.

November 26, 2001: King Gyanendra declares a state of emergency as cease-fire comes to a bloody end.

It is in the nature of communist revolutions, many scholars have noted, to screw up a good cappuccino. Lying on the hotel bed my second morning in Kathmandu, I find that the medicinal properties of caffeine have assumed heroic proportions in my jet-lagged brain. There was airport Nescaf├â┬ę in New York and London, anemic hotel java in New Delhi, and watery airborne muck everywhere in between. Now, all I really want from life is some strong coffee. While I wait for room service to deliver the cure, I try the phone number one more time. I’ve dialed it for a day with no results. The telephone system in Kathmandu is inexplicable. I can’t tell if I’m getting no connection, or no one is answering, or I’m dialing the wrong number.

If someone ever does answer, that person is supposed to know where the guerrillas are. The insurgents, elusive revolutionaries from the hills, call themselves Maoists. Nobody paid attention when this hard-line faction of communists declared a “people’s war” back in 1996. The guerrillas were almost without weapons, and did little more than organize propaganda rallies for poor farmers in Rolpa district and other remote western zones of Nepal. But they’ve earned a reputation for severity├éÔÇöbanning alcohol, cutting off the hands of hashish dealers, and forcing village gamblers to eat their decks of cards. And last September the revolution entered a new, militant phase. A thousand guerrillas appeared from nowhere to blast their way into Dunai, the remote western town that served as the gateway for Peter Matthiessen’s trek into Inner Dolpo in The Snow Leopard. The pace of attacks has picked up since then: This April the Maoists stormed two remote police outposts├éÔÇöknown here as POPs├éÔÇöin the western towns of Rukumkot and Dailekh. The posts were overrun at night by hundreds of guerrillas hurling homemade hand grenades in human-wave attacks. Seventy police officers were killed, some of them executed after they had surrendered. On July 7, another 39 were killed in three simultaneous attacks in Lamjung, Gulmi, and Nuwakot districts, west of Kathmandu. Smaller skirmishes are now a weekly event, as the Maoists drive the government out of whole swaths of the countryside, stripping the dead and the prisoners of rifles, ammunition, and shoes. With up to 5,000 full-time fighters, and as many supporters in part-time militias, the biggest problem the Maoists face is having more recruits than equipment.

Most Western tourists and trekkers, including the 40,000 Americans who visit Nepal each year, have dodged the sharp edge of this unsheathed war. But that grows harder every day. In February, a Chinese development worker, the first foreigner, was injured when Maoists raided a dam project to steal dynamite. Still, in Kathmandu, there is denial.

I punch the digits on my phone, and this time someone answers. “Sorry, sir,” the voice replies in trembling, terrible English. “No Maoists.” He doesn’t know what I’m talking about, he’s never heard of the Maoists, there’s nobody here by the name I’m asking for. I leave a message and hang up. A couple of minutes later, there’s a knock on the door. It’s room service with the cappuccino, which smells of everything good. I take one sip, and the phone rings.

It was then, with the heavy cup still in my hand, that words began to drift toward other meanings, that reality began to melt into new and unstable forms. Like Alice, I’d swallowed a potion that would take me into a Wonderland, a kingdom of retrocommunism unlocked by secret handshakes and punctuated by thousands of clenched fists. Time would now flow backward, the 21st century giving way to Year Zero, Boeings yielding to bows and arrows, video night in Kathmandu becoming firelight in mud huts. The forecast for the glorious future would look a lot like 1950. It is the same voice on the phone, but different. His English and his attitude have suddenly improved. “You want to meet the Maoists?” he asks. Voices argue in the background, and then he announces that it is time for a journey. He can’t say what kind of a journey it is, whether it will be to the east or the west, into the Himalayas or down to the subtropical plains. He can’t say how long we will be gone. He won’t even tell me who he is.

I write down an address. “You must be there in 15 minutes,” he says.

This is impossible, but we try. I run downstairs, rip photographer Seamus Murphy from the lunch table, throw money at the front desk, and we walk out with only the clothes we are wearing, spare socks, and the contents of our knapsacks.

The taxi creeps through the crushing traffic of Kathmandu, swerving around bicycle rickshas and sacred cows sleeping in the stream of Toyotas. We turn along the Royal Palace, a Himalayan Elsinore surrounded by spear-point fencing that serves not to keep danger out, but to trap it inside. (The massacre of the royal family is less than two weeks away.) Our driver turns down Durbarmarg; we cross a bridge, enter a neighborhood that foreigners never visit, and are dropped on a busy sidewalk, 20 minutes late. I watch the passing stream of humanity, sari-clad shoppers and topee-topped deliverymen, students in jeans and dusty construction workers in sandals. They are remnants of a Nepal that is already fading away.

A young man in a tan shalwar kameez├éÔÇöa Pakistani-style long shirt over pants├éÔÇösteps out of the traffic. His eyes are burning in his brown face, and his smile is a trick. “Hello, sir,” he says. “Come with me.” Without waiting, he folds back into the flow of people, walking fast. The rabbit hole opens up, and we, soon to be followed by the entire nation, fall in.

They definitely need some new astrologers at the royal court in Kathmandu. It was the seers of the spheres, casting their ancient divinations and decoding the celestial motions, who laid the trap. They calculated that the heavens were not in alignment for a royal wedding. The crown prince had picked the wrong bride. The auspicious date and the harmonious mate were still years in the future. The queen listened to them too closely├éÔÇöor, some say, they listened to her too closely├éÔÇöand rejected her son’s plan to marry his girlfriend.

Intrigue is the Nepalese national pastime, factionalism the country’s historic curse. Crown Prince Dipendra’s bride-to-be, Devyani, and Queen Aiswarya were both members of the most powerful political clan in Nepal, the Ranas, who ruled the country from 1846 to 1951 in an inherited dictatorship that allowed the royal Shah Dev family to retain the crown. But the Ranas long ago split into rival branches, and Aiswarya could not stomach her son’s choosing from the wrong side of the family tree.

On June 1, 29-year-old Dipendra├éÔÇöpopular heir to the throne of the world’s only Hindu kingdom, inheritor of the Lost Horizon├éÔÇödid something that was, the astrologers admitted later, not foreseen in his charts. He reportedly drank some scotch, smoked some hashish, and then committed regicide, patricide, matricide, fratricide, sororicide, and finally suicide. Shortly after being ejected from a family dinner for drunkenness, Dipendra returned with a submachine gun, an assault rifle, a shotgun, and a pistol, and killed everyone he could, beginning with his father, continuing through most of the royal household, and ending with himself. When it was over, ten people were dead.

Like Hamlet, the crown prince seems to have been driven to violence by the inbred madness of a rotten kingdom. Like Ophelia, the star-crossed young royal killed himself at a pond in the palace garden. But you don’t have to look to Shakespeare for analogies: Nepal’s own history is littered with examples of blood on the crown, including a spectacular 1846 massacre, instigated by the queen, that cut down more than 30 members of the elite.

Still, the murdered king had seemed the very model of a modern minor monarch. Birendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev, a descendent of the original Gurkha prince who conquered and united Nepal in the 1760s, had been educated at Eton and Harvard, and became absolute monarch at age 26 upon the death of his father, King Mahendra, in 1972. Unlike his father, who had dissolved Nepal’s first constitutional government in 1960, imprisoned most of the dominant Nepali Congress Party leadership, and banned all political activity, Birendra was a relatively liberal ruler, the glue that held together this country of 23 million people├éÔÇöa patchwork of 60 languages and a score of ethnic groups├éÔÇöas it opened to the outside world.

The political system, however, remained tightly restricted until 1990, when street demonstrations forced Birendra’s royal hand. He cemented his popularity by assenting to democracy├éÔÇöalbeit a system where weak prime ministers are squeezed between an unaccountable monarchy and a parliament of cynical, corrupt coalitions. Democracy has now given birth to 92 registered parties, among them 15 “legitimate” communist parties that have often overlapped in coalitions, and even names. The Kathmandu phone book currently lists the Nepal Communist Party (United Marxist Leninist)├éÔÇöthe main opposition in parliament├éÔÇöas well as the Communist Party of Nepal (Marxist Leninist), the Nepal Communist Party (Democratic), the Nepal Communist Party (Masal), and its rival-by-one-letter the Nepal Communist Party (Mashal). All of them despise the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) for abandoning the electoral process in 1995 to go underground.

Despite the patina of modernity in Kathmandu, the country still suffers the aftereffects of isolation. High-caste Hindu Brahmans and Chetris of Indian descent, called Aryans, control the government, the economy, and much of the best farmland, while low-caste farmers and untouchables are marginalized. Almost half the country’s people, including the Sherpas, are “tribals,” mountaineers of Tibeto-Burmese descent, usually Buddhist or animist in their beliefs. There are long memories here, and hill people resent that Hindus arrived centuries ago as refugees, only to impose their culture, alphabet, rulers, and religion.

“It is a country made of groups that have long histories of suspicion toward each other,” says Joe Elder, director of the Center for South Asia at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. “The farther you go out from the Kathmandu Valley, the more people insist that they are Gurung, or Tamang, or Magar, not Nepalese.”

Modern geopolitics plays out along parallel lines. Never conquered by the British, Nepal swelters in the economic and political shadow of India, the regional superpower. Since the enemy of my enemy is my friend, Nepal has reluctantly turned to China. The realpolitik issue for China is Tibet. As long as Nepal clamps down on its tens of thousands of restive Tibetan exiles, Beijing supports Kathmandu, not the Maoists.

Squeezed between giants and pricked by overpopulation, deforestation, and corruption, many resentful Nepalis are vulnerable to conspiracy theories. (“In my experience, there’s at least one conspiracy theory for every person in Nepal,” Elder notes.) Ideologues who promise a war on “class enemies” and the satisfaction of ancient grievances find willing listeners. The Maoists’ elusive leader, Comrade Prachanda (Nepali for “fierce”), constantly denounces the country’s Hindu Brahman leaders, despite being a Hindu Brahman leader himself, and has whipped up nationalist paranoia with predictions of an imminent Indian invasion. Most of the time, however, Prachanda leaves the talking to the guerrillas’ media-savvy second-in-command, Baburam Bhattarai, an Indian-educated architect fond of gassy vows to “hoist the hammer-and-sickle red flag atop Mount Everest.”

The explosion of all these tensions came not with the royal massacre, which left the nation in stunned silence, but three days later, when├éÔÇöas in Hamlet├éÔÇöthe dead king’s brother, 55-year-old Gyanendra, assumed the throne in a ceremony whose very haste prompted suspicion. Many Nepalis did not believe├éÔÇöwould not believe├éÔÇöthe official verdict that the massacre was the act of a single, drug-addled prince. It was a double cross by factions of the Rana family; it was a coup plot by India and the CIA; it was Gyanendra, who, conveniently absent, used his despised son Paras to orchestrate the killings. Comrade Prachanda, rumored to be hiding in India or London, issued a statement calling the carnage and its aftermath “a serious political conspiracy.” On June 4, thousands of demonstrators, fronted by communist students, took to the streets. Fourteen curfew violators were shot and wounded by police. Two editors and the publisher of Kantipur, a Kathmandu daily, were arrested after publishing an anti-royal article by Baburam Bhattarai. The Maoists launched a string of symbolic bomb attacks, dynamiting the house of the unpopular prime minister, Girija Prasad Koirala, and the chief justice of the supreme court, who led the dubious investigation into the massacre.When King Birendra, his skin painted pink with tikka paste, was cremated on a funeral pyre, the old Nepal went up in flames with him.

The Maoists are perhaps the only beneficiaries of this national nervous breakdown, with thousands of men and women scattered in the hills, lodged in remote base camps in Rolpa and Jumla districts, settled in small villages down on Nepal’s flat southern terai, or living over the next ridge somewhere near the Tibetan border. At a time when the entire nation is disarmed by events, the Maoists are bristling with weapons; as the government founders in discord, the guerrillas are laying out five-year plans; while Nepal’s archaic social order crumbles under corruption, the insurgents spread hyperrational fantasies of a cultural revolution that will wipe the slate of history clean. The rebels already operate in a third of the country; they will only expand, thanks to the bloody discrediting of the ancien r├â┬ęgime.

Despite the evasiveness of our Kathmandu contacts, we gather that there is going to be a big rally somewhere in the foothills. Although the guerrillas don’t carry around copies of Mao’s Little Red Book, they have adopted the Great Helmsman’s essential strategy: using the countryside to encircle the cities. They have chased away the national police and established broad aadhar ilaka, or base areas. They have set up “people’s courts” and village councils in a few places, but now they are going to declare a new shadow government at the multidistrict level, their biggest step so far. Our role, apparently, is to attend the rally and spread their propaganda.

We’re not surprised, therefore, to find ourselves driving westward on the Prithvi Highway that first day. If the Maoists have a homeland, it is a cluster of five districts├éÔÇöRukum, Rolpa, Salyan, Jajarkot, and Kalikot├éÔÇöin the midwest, a jagged, densely cultivated hill country dominated by the Magar ethnic group, far beyond the tourist orbits of Annapurna and Pokhara. We head out in a taxi├éÔÇöa Korean microbus├éÔÇöcrowded with Seamus, our Maoist guide, our driver, and me, plus three Nepali men who turn out to be stringers for Kathmandu dailies. Still unsure of our destination, companions, and prospects, we keep our eyes focused on the countryside, the dry-season rice paddies decorated with tumbledown huts.

We turn south before reaching Gorkha, a region immensely popular with trekkers├éÔÇöand, increasingly, with Maoists. Although the guerrillas have ignored tourists so far, the U.S. Embassy cautions Americans against visiting Gorkha and 16 other districts, from Kalikot in the far west, to Sindhuli, east of Kathmandu; it restricts its own staff from traveling in Jajarkot, Kalikot, Rolpa, Rukum, and Salyan. With Maoists operating in 60 of the country’s 75 districts, trekking companies like Geographic Expeditions and Snow Lion Expeditions have canceled or rerouted some excursions.

Not far from Buddha’s birthplace of Lumbini, we pass a troop of rhesus monkeys waiting impatiently for the wheels of our taxi to split open the unripe fruit they have deposited on the asphalt. We overtake two long files of teenage soldiers, a 600-man battalion of the Royal Nepalese Army marching westward, clutching automatic rifles. So far the army has stayed in barracks while the demoralized, poorly trained national police have done all the fighting. King Birendra had been reluctant to escalate the conflict, convinced that negotiations were preferable. Within a few weeks of Birendra’s death, however, Gyanendra would verify his conservative reputation by proclaiming a draconian National Security Act, permitting the arrest of anyone, anywhere, without any explanation. For now, the soldiers we pass, and the guerrillas we are heading toward, are all blissfully ignorant of the approaching storm.

By dawn the next day we leave behind asphalt and turn up from the flat terai. The first thing we see is a cardboard effigy of despised prime minister Koirala dangling from a lamppost: We are in contested country now. We swing up and over the Mahabharata mountains and pick up the Bheri River valley. Our leader, another Kathmandu supporter of the guerrillas, is sweating inside a down vest; he never removes his hat, dark glasses, or the earphones of his cassette player. With rigid discipline he gives no explanations, offers no answers, names no destinations.

The taxi driver, on the other hand, is a verbose fraud. The deeper we get into hostile territory, the more he quivers with fear. He invents a series of imaginary breakdowns, pulling over at any pretext to announce that it is “impossible, sir” to continue. Each time, after crawling under the van for inspections, I shame him into pushing on, but when he begins surreptitiously pumping the gas and brake pedals, ascribing the van’s lurching to “clutch broken, sir,” I drag him from behind the wheel and start driving myself.

The correspondents are equipped for the mountains in slacks and loafers. They speak Inspector Clouseau English, and pander to us all day with a stream of preposterously false declarations about the terrain, the travel time, and the villages we pass. If you like dust, bumps, bad food, sweaty seatmates, misinformation, near misses with trucks, and Bollywood music, the road trip has its moments.

We rattle down washboard roads and ascend toward the middle hills of the Dhaulagiri Himal. We pass a few POPs, outposts where frightened cops hide behind sandbags, and in the late afternoon we reach a nameless, straggling village where policemen stand on the roofs, scanning the valley. We check into a smoke-filled bunkhouse, and at five the next morning, under an icy half-moon, set off again. After dawn we try to sneak past the capital of Rolpa district, a heavily garrisoned town called Libang. We disembark, somehow manage to convince the authorities that we are just a badly confused trekking expedition, and continue on foot, leaving the road├éÔÇöand electricity, the government, and the taxi driver├éÔÇöbehind.

After a couple of hours, we step along a swaying footbridge high over a green, boulder-strewn stream and find a tattered red flag with a hammer and sickle snapping in the breeze. “We are now entering area of topmost Maoist influence,” one of the correspondents explains├éÔÇöthe aadhar ilaka, the home of the revolution.

One more nameless river valley and we trip lightly across a second cable bridge to find an unarmed woman in camouflage sitting at a picnic table, watching the bridge. She pays no attention to us, and we march quietly on, turning left beneath a “Martyrs Arch”├éÔÇöa cement gate dedicated to the 2,000 guerrillas and civilians the Maoists say have been killed in the war so far. Within the hour we are waiting in a farmhouse while messengers are sent. A handful of curious men appear, loitering outside the hut, reluctant to come in. A couple carry astonishing muskets obsolete since the American Civil War. One has a pistol, but most are unarmed. They are wearing flip-flops. Incredibly, these losers are the guerrillas.

There are three rules of travel in the Maoist heartland. Sitting in the safe house, we are briefed by the leader of the ragtag squadron, a 42-year-old former school principal who speaks fine English. He is an ethnic Gurkha and goes by the nom de guerre of Sanktimon, after the hero of a cartoon on Indian television. Sanktimon means “strong man,” but it’s not for his muscles. “It is because I am strong in ideology,” Sanktimon offers with a wide grin. He explains the route we will follow and then the rules: (1) No taking pictures without permission. (2) No going to the bathroom without a guard. (3) You must give a speech.

Within hours, Seamus will disregard the first rule completely; the second one proves deeply problematic; the third rule is one I immediately reject.

We gloss over these disagreements and seal the deal with an exchange of lal salaams, a revolutionary slogan that means “red salute” and is always accompanied by a clenched fist. We quickly march off in single file, crossing more paddies and then heading up through a beech forest onto a switchbacking trail that becomes, eventually, the steepest surface I have ever climbed. Hours later we reach a razor-thin, foggy ridgeline at 5,000 feet. The slopes are stacked with terraces even here, the paddies no wider than a single ox. Nepal’s population has tripled since the 1940s, and the relentless search for arable land has increased deforestation and erosion massively while still not producing enough to eat. Exclusively agricultural, western Nepal is nonetheless a net importer of food. Hungry, impoverished peasants are easy recruits to the Maoist cause, with its promise of a government by, for, and of the small farmers.

Sometime after dark, the sky explodes with rain, and we tumble into a puny hamlet where dozens of guerrillas wait in huts. These are real Red Army troops, main force soldiers in neat camouflage uniforms. They carry Lee-Enfield .303 rifles, relics from World War II but state of the art compared to the flintlocks carried by our patrol.

In a dark, smoky room we eat with the soldiers, wolfing down rice and lentils with our fingers. Comrade Strong Man won’t answer questions about the movement, its ideology, or his own position within the group├éÔÇö”I am just someone,” he says, dismissing my questions. The only foreign correspondent they’ve seen before, he says, was a dyed-in-the-wool communist from The Revolutionary Worker, the weekly newspaper from Chicago, and Strong Man assumes we’re here to cheer the revolution on. He is thrilled to host fellow travelers and promises to find two spoons for “the gentlemen comrades” by the next meal. Out here, spoons are still in the future, and metal of any kind is so rare that even plowshares are made of wood. In the soft light of the cooking fire, surrounded by men clutching ancient weapons, we seem to be regressing toward the Bronze Age.

We sleep packed elbow-to-ass amid a dozen snoring guerrillas. At 2 a.m., I am jolted awake by a shower of blows. The guerrilla on my left is twitching in the grip of a nightmare. I lie on the stone floor, staring at the ceiling until 5 a.m., and then we are hiking again.

In meeting the Maoists, we’ve achieved exactly what most visitors to Nepal have been hoping to avoid. Although few foreigners have heard much about the guerrillas├éÔÇöthanks to a suppressed local news media and a see-no-evil tourism industry├éÔÇöthe two groups are already beginning to meet on the remote mountain paths that they share. Some trekking groups have bumped into Red Army patrols, who have pressed them to “donate” binoculars and sleeping bags to the revolution, but in most incidents the guerrillas and hikers have passed without speaking.

The real squeeze is happening back in Kathmandu. In March of last year, many foreign-owned businesses were approached by guerrilla representatives demanding money. Speaking on background, to protect his business, the head of one major American trekking company explained it as “a choice between operating here or holding to your ethical standards.” Like several other foreign outfitters, he paid $1,400 to ensure that the Maoists left his clients alone.

Funding the very revolution that threatens you may seem self-defeating, but taking a stand against corruption in Nepal is like pissing up a rope. Extortion was once the privilege of the royal family, but since democracy arrived, in 1990, there are many more hands in the pot. Foreign aid funds evaporate; trekking fees earmarked for irrigation projects and reforestation are siphoned off. Until the practice was exposed in 1995, Queen Aiswarya received three million rupees annually from the oil monopoly and a rake-off from all foreign aid that passed through her powerful Queen’s Coordinating Council. The weak do what the powerful teach them: Traffic policemen shake down motorists, and beat cops hit up restaurants for protection money. By this standard, the Maoists are quite reasonable. They send neatly written, personalized letters to hotels, businessmen, teachers, NGOs, and even government offices requesting the payments. In typical Nepali fashion, they will negotiate the price. The business of extortion has now become so lucrative that the country suffers from a plague of fake Maoists. A group of tourists rafting in the Chitwan nature reserve was robbed last year by “guerrillas,” but an American diplomat told me that, of the four to five such encounters reported by tourists so far, only two involved genuine Maoists. In an effort to fight this corruption of their corruption, the Maoists began issuing receipts on official revolutionary letterhead, but they had to abandon this effort when├éÔÇöalso in typical Nepali fashion├éÔÇöfake receipts were rushed into circulation.

Pervasive government corruption has become the single greatest source of support for the guerrillas. “Look at Kathmandu,” says Barbara Adams, a textile expert living here since the early 1960s. “Most of the palaces were built with corruption money, taken from development funds and foreign aid. It’s an aid mafia, literally.” Originally from New York, Adams knows the inner workings of the Kathmandu elite better than almost any foreigner, having been the kanchi swasni├éÔÇö”unofficial wife”├éÔÇöof a prince in the 1960s. She still has the Sunbeam Alpine sports car given to her by King Mahendra’s brother.

Like a surprising number of people in Kathmandu, including intellectuals, members of parliament, and even army officers, Adams is eerily sympathetic to the Maoists in the hills. She believes they are patriots, fighting against a corrupt order. They actually care what happens to the majority of Nepalis, who can’t read and have no electricity. She quotes a Nepali friend: “We’re all Maoists now; there is no alternative.”

But the lack of alternatives is the very problem. King Birendra was quietly sending signals to the Maoists, who praised him and sent condolences on his death. The new government is a cipher, but will likely take a harder line to protect its wealth and position. Even a Sunbeam-driving sympathizer can see that every day that passes without a solution makes things worse. Like the Shining Path, the Khmer Rouge, and Chairman Mao himself, the more the guerrillas fester in mountainous isolation, the more paranoid and intolerant they become. “The longer this goes on,” Adams notes, “the harder the Maoists will get. And the next thing you know, we’ll have a Taliban.”

We summit one of Rolpa’s infinite peaks, and suddenly we’re looking down on the site of the rally. It is a broad, rounded spur the size of several soccer fields, reaching out over a deep valley. We hike down, pass beneath another Martyrs Arch and find a half-dozen huts and a long schoolhouse├éÔÇöthe hamlet of Babhang. A battery-powered public address system is lashed to poles, and a packed-earth platform with chairs awaits the speakers. After only a few minutes, there is the sound of chanting in the distance.

They come in village by village, spilling down into the rally with unfeigned hoopla. Sixty from one hamlet, 30 from another, 40 from a third, a stream of desperately poor, excited people waving their fists in the air. The men wear bland homespun skirts or worn-out tracksuits; the women dress in saris of royal blue, emerald green, earthen reds, and otherworldly purples. Within minutes, a second column begins to stream over a high peak in the distance. As they spot the rally site, men discharge their blunderbusses in thundering blasts that echo back and forth in the hills. A third column appears, snaking steadily up from the valley floor, hundreds more carrying banners and blasting off their own guns in reply.

The largest guerrilla rally I’ve read about featured 700 people; within an hour there are a thousand here, and then twice that, delegations from 52 villages across Rolpa. They march in crude military lockstep, barefoot or in blown-out sandals, and arrive chanting call-and-response slogans (“Communist Party of Nepal, LONG LIFE!” and “Marxism-Leninism-Maoism, LONG LIFE!”). Perhaps 200 Red Army soldiers wait, stonefaced. They’ve got Enfields├éÔÇölike the canvas sneakers on their feet, captured from the national police├éÔÇöand wear counterfeit Lowe Alpine backpacks. Comrade Strong Man appears from time to time to shout, “Here are the masses! The masses are coming!”

Village bands arrive, tooting on horns and banging drums. A group of black-clad boys dances into the rally, bells jangling on their ankles, and girls from the remotest peaks, who walked three days to get here, giggle and cover their faces at the sight. Every few minutes another black-powder gun detonates, launching a huge doughnut of smoke into the sky.

By noon there are 4,000 people, and still they pour in. A village militia arrives from some other century, clutching bows and carrying quivers of neatly fletched arrows, chanting, “No to feudalism!” Next is an entire girls’ soccer team armed with blue tracksuits and muskets. Student groups traipse in with neat flags, and associations of untouchables, and women’s groups chanting, “Murder and rape must stop!” The Maoists can sound progressive: They vow not only to fight police corruption, but to punish spousal abuse and hunt down rapists, while recruiting women guerrillas and political cadres. Likewise, they challenge the ancient caste system, which is nothing but racism, and the untouchables are among their most eager recruits.

Five thousand, six thousand, eight thousand people. The crowd fills the entire ground, each group parading under the Martyrs Arch with chants, and then marching to an assigned spot where they collapse into densely packed clusters. They open their umbrellas to make shade and light up chillum pipes, little chimneys of tobacco and marijuana casting puffs of smoke over the scene. There’s a flurry of excitement when a government helicopter circles (high) overhead, scanning the rally, but they might as well read it in the papers: The Nepali journalists are busy taking notes, and their dispatches will hit the Kathmandu front pages in about four days. (“maoists declare admn, vow to fight army.”)

Strong Man spots me taking my own notes. “You are preparing your speech,” he announces. No, I remind him, I won’t be giving any remarks. He seems disappointed but counters with the good news that two spoons have been found. A young guerrilla spoon-bearer is assigned to serve us lunch.

In midafternoon, with 10,000 peasants packed onto the spur, the propaganda starts. The main event is the declaration of the shadow government in Rolpa and several adjacent districts, and the new leaders of the revolution’s first official government are invited to step forward. There are 19 of them, a cross-section of the movement itself├éÔÇöa few tough Magar peasants from Rolpa, much like the attendees at the rally, but also an ambitious student leader from Kathmandu, and several older professional communist politicians. Comrade Strong Man turns out to be Rolpa’s new representative of “the intellectuals.” Invoking the name of the almighty Prachanda, he delivers a 30-minute speech about the teachings of the leader they follow but never see; after him the new vice-chairman gives a speech, and after him the district’s new top man, Chairman Santosh Buddha, gives an amazingly dull, hourlong talk. A typical politician, Buddha is lofty and affected, and seems to have practiced looking thoughtful in a mirror. Despite the sunshine, he preens about in a gray Gore-Tex coat, the only one at the rally. Seamus and I call him Chairman Gore-Tex behind his back.

My speech is a huge hit, although I have no idea what I said. With dusk approaching, Strong Man drags us onto the platform for a ceremonial welcome. Chairman Gore-Tex pins us with red ribbons and smears a thumbful of pink dye between our eyebrows, the traditional tikka blessing. As he lays a garland of lali guras flowers around my neck, he explains that these red blooms grow only at high altitude├éÔÇö”like the revolution.” I try to run for it, but it is too late: They push me at the microphone.

The second I open my mouth (“Greetings to the people of Rolpa district”) the crowd starts giggling. In a region where even radios are an unknown luxury, most of them have never heard a foreign language, and my brief clich├â┬ęs about peace and justice are buried beneath a rolling wave of laughter. After a lal salaam and a pathetic clenched fist, I slink offstage to a ragged cheer. I’ll never survive my Senate confirmation hearings now.

I’m replaced by another speaker, and then another, on through dusk, politicians, newly appointed cadres, the women’s representative, and then, in the dark night, a string of guerrilla officers, hard men in camouflage speaking hard words about “taking on” the army in a coming war.

By 10 p.m. all 10,000 Maoists├éÔÇöarmed men and women, kids and babies├éÔÇösimply lie down where they are, some sleeping, others smoking, everyone wrapped tightly in shawls against the mountain chill. I head for the alfresco bathroom, trailed by the usual guerrilla guard. This time I’m ready. Hidden in my backpack, I’ve found a handful of chemical light sticks, and I break a green one and give it to him. He’s never seen one before and rushes off in delight to show it around, leaving me in peace. The beam of my flashlight illuminates the bushes around me: wild cannabis, the source for Nepal’s hashish industry and one explanation for the laughter during my speech.

Back at the hut, my guard sits in a circle of Red Army men, their faces glowing green from the soft chemical light. One of the guerrillas throws an arm around me and says, “Good speech.” The valley still echoes with the words of the Red Army’s top officer, Comrade Lifwang. “War is a challenge,” he says. “Without war, nothing can be changed.” So many military terms here are borrowed from English that I can follow along as he describes a battle just days ago, in eastern Nepal. He tells of the first platoon attacking the police. He pantomimes a police helicopter circling overhead, trying to relieve the besieged POP, the machine finally chased away by rifles cracking in the night. The second platoon comes forward, and finally the POP is overrun. Victory for the revolution. I pass out.

By first light there is not a single person left on the field. I wander over the barren saddle of the mountains, wondering if the 10,000 chanting peasants were a dream, but the proof is on the ground, the dust still imprinted with the shapes of their missing bodies.

The guerrillas’ philosophy too is ghostly. So far we’ve had a propaganda massage without getting to ask any questions ourselves. Finally, at 10 a.m., with cold clouds blowing in, I am summoned to the schoolhouse, where the entire gang is assembled for a press conference. Gore-Tex, Strong Man, some Maoist schoolteachers, and several vice-flunkies are lined up on benches.

I sit on my bench, scuff my feet in the dirt, and finally ask the question I should have asked the crowd yesterday: How many people must die? The guerrillas like to cite the Shining Path as their fellow travelers in the Maoist cause. I point out that 30,000 people have died in Peru, without a Red victory. If that many people die in Nepal, will the revolution still be justified?

Yes, they all nod immediately. The true face of the revolution at last. “To protect a whole thing,” a schoolteacher says, “a part can be damaged. It is the rule of nature.”

Comrade Strong Man elaborates: “A big part of the people here believe it is not necessary to solve Nepal’s problems with violence.” He brushes aside this natural reluctance. “We clear their mind of this idea,” he says. “The people’s war is necessary.”

They dismiss offers of peace talks from the government, tricks designed to fool the people, weaken the country, and deliver it to the control of India. Ominously, Gore-Tex vows a “protracted war in rural areas,” and “armed├âÔÇ░urban rebellion,” the first hint of a guerrilla war in Kathmandu.

They descend quickly into jargon. They are for dialectical materialism and against reactionary power. Chairman Mao’s Cultural Revolution, in which mobs beat “class enemies” through the streets, was good, and will be imitated as soon as they come to power. Colonialism, feudalism, imperialism, capitalism, and revisionism are all bad. Peasants are good and politicians are bad. On this animal farm, four legs are good and two legs are bad.

Their policy about foreign tourists is clear: The more, the better.

“Not any foreign person is to be disturbed,” Gore-Tex announces, as Strong Man nods. They actually invite trekkers to visit their areas├éÔÇöwith permission├éÔÇöbecause they believe Westerners will be seduced by Maoism and spread the revolution to Europe and America. It’s a Red Tourism offensive. “We will inspire them to flourish the same movement in their country!” Strong Man boasts.

Strong Man presents me with several pages ripped from his notebook. This document begins with an error-riddled manifesto├éÔÇö”the C.P.N. (Moist) is guided the ideology of Marxism-Leninnism-Maosim against the reactionary power of Nepal which is preserved by Indian expansionis and world imperialist”├éÔÇöand continues with an executive summary of the press conference, which bears no relation to any of the questions I asked.

Q. How do you face Royal Army.

A. We will face it with the power of the people.

Q. How do you forward the production.

A. We forward it with the help of people.

Q. How do you bring about indigenous society.

A. We bring it according to Lenin’s ideology.

Q. How do you forward Negotiation with the government.

A. We are fighting total war.

As we talk, an early tendril of the monsoon season blows in, a thick, blasting rain of tropical density and high-altitude chill. We exchange endless good-byes in the dripping hut, while guards are found to escort us out of the base area.

During the wait, Strong Man teaches me the secret Red Army handshake (fore-fingers, pinkies, and thumbs meet in a tri-angle; then rotate on the thumbs into a soul shake). A dozen guerrillas crowd around to give me the shake. Overwhelmed by emotion, I hand out the remaining light sticks.

In a sopping-wet ceremony, Gore-Tex drops more flowers around our necks and rubs more tikka on our foreheads. He gives all of us, including the Nepali journalists, sealed airmail envelopes. I naively assume that these contain a letter, or a certificate, or some propaganda, and stuff mine into my pocket, ready to get moving. As I walk out the door, I notice that the Chairman’s Gore-Tex coat has soaked through completely. It’s as fake as he is.

The descent is a hallucination. We set off into howling rain, speed-hiking hour after hour in a downpour. We’re still wearing our lunch clothes from a week before; our raingear consists of garbage bags. We trudge through mud, ford streams, and cross cliffs on slate paths two feet wide. At times the guerrilla walking point disappears into fog and mist. Landscapes open abruptly, and worlds disappear between glances. There are few people on the trails. A herder driving goats and cows stands still and looks askance; in one barefoot hamlet, we draw the entire population in a shy, silent crowd. A patrol of Red Army soldiers hustles past, without even a lal salaam. Bells tinkle in the distance, and strange howls float down from the slopes. One long day, and we are out of topmost Maoist country. Climbing now with night coming on, we hit the road and hitch a ride into Libang.

At some point in here I drag the crumbling, soggy envelope from my pants pocket, slide a finger down the seal, and discover that it contains money. Not a letter, not a certificate, not a propaganda flyer, but a bribe. About $5 worth of rupees. Now I’m as dirty as everyone else in Nepal.

Alice wakes up from her dream, and time begins to move forward again, bringing with it small signs of the depressing realities that grip present-day Nepal. In Libang, I meet Chairman Gore-Tex’s nemesis, Harikrishna. He’s the government’s chief district officer for Rolpa, a conceited, high-caste politician who shows up an hour late, awash in flunkies. Although he can’t even visit most of his guerrilla-controlled territory, he insists that the Red Army rules by fear alone. “They have no support,” he tells me, cleaning his nails with the tip of a key.

We meet a 75-year-old refugee, Ratibhan Oli, one of hundreds of people the Maoists have chased out of their base areas. These are the “revisionists,” people who won’t, for one reason or another, toe the party line. And at a mud-floored boarding school the same day, 300 students assemble on the parade ground to hear me, at the insistence of their teachers, give another speech. Staring at their upturned faces, beneath guard towers, I am at a loss. Should I tell them to pay no mind to communist dingbats and court astrologers? Should I point out that the Maoist revolution will inevitably turn inward and eat its children, like every revolution everywhere?

I can’t think of a damn thing to say.

Another day of brutal road travel and a prop plane back to Kathmandu. In the terminal, I spot a plastic box for donations to the Red Cross and shove the remaining rupees, the Maoist bribe money that we didn’t spend on Fantas, through the acrylic slot.

Soon the king will die. Kathmandu, like the countryside, is already seething, as if by premonition. There’s another general strike on, one in a series that has paralyzed transport and turned the city into a ghost town. For days we wander avenues so quiet that the holy cows are confused by the lack of traffic and moo in despair. Without the pollution of tailpipes, the fresh mountain breeze is a reminder of an old Nepal. But the empty sidewalks and shuttered cybercaf├â┬ęs of Thamel also look like another Nepal, some future place where the Maoists have come to power and dispersed the modern world with a harmless cultural revolution, emptying the city like the Khmer Rouge with good manners.

There are Nepali journalists who predict just such a Maoist takeover, but that worst-case scenario is unlikely. The army will deploy, the old guard in Kathmandu will rally to defend itself, and India, China, and the United States will stir themselves from indifference. “The Maoists are a real problem,” says University of California, Berkeley professor emeritus of political science Leo Rose, a leading Nepal expert. “But it’s hard for me to see them overthrowing the present government. What are they offering? They don’t have any achievements or accomplishments. My own guess is they’ll be an irritant, a problem, but not an alternative.”

It is more likely that the Maoists will be undone by their own quest for ideological purity, by their faith in a violence that, as they themselves admit, is not supported by the Nepali people. The U.S. Embassy in Kathmandu argues that there may be as few as 2,000 hard-core communists, and that, as an American diplomat there told me, the “masses” backing the Maoists “are really ordinary people more disgusted with circumstances than Maoist in ideology.” Their support for the guerrillas is “wishful thinking in a desperate situation,” as Nepali political scientist Vijaya Sigdel puts it. But the more the Maoists expand, the quicker the people will learn that opposing a corrupt government is not the same as supporting a fanatical insurgency. Nepal can still evade the dark garden of Maoist dreams, but the exceptional kingdom is already losing its distance from the world, becoming instead a troubled, unexceptional place.

In the last days of the old Nepal, it is lovely to walk the strike-bound streets or roll about town in rickshas, pausing to watch aimless bands of students and communists march listlessly through the city, lifting their fists, occasionally tossing a brick. There’s something wonderfully feeble about the scene. Perhaps the Maoists’ grim ferocity will yet founder in the traditional incompetence of Nepali politics. There is always the hope of farce, rather than tragedy.

I stop around the royal palace a few times, but nobody is allowed to visit. The Gurkha guards in puttees and plumed hats shoo me away, and I have to settle for looking through the fence at the lush grounds, the pine trees, and the ornamental gardens.

In a few days the king will be dead. Long live the king.