It’s not easy to add up all the ways in which Lance Armstrong has earned the title of American hero.

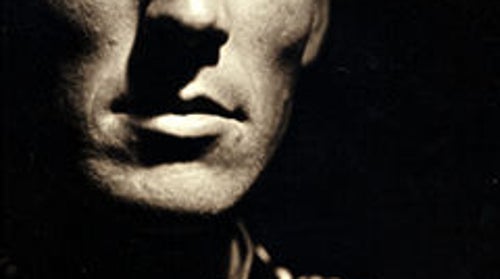

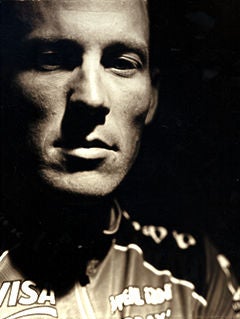

Lance Armstrong

Lance Armstrong

Lance Armstrong

First he was the fiery phenom, a brilliant athlete on the brink of greatness. Then he showed us the vulnerable, terrified, but always valiant young man who barefisted the cancer that nearly killed him. And then he became the determined comeback artist, reasserting himself step by step. Finally, in a rush of glory, he was the triumphant winner of the 1999 Tour de France; husband, father, and mature champion—a man now “leaner in body and more balanced in spirit,” as he puts it.

To which we would submit one more thought: A world that gives us Lance Armstrong is a world where it’s a lot more fun to ride a bike.

In the following pages, Armstrong and his coach, Chris Carmichael, reveal the surprising fitness strategy that got Lance ready for last year’s Tour—a plan that can put you at the head of the pack, too. After that, we celebrate the distinctive regional styles of bicycling in the U.S.A., and offer an array of bike reviews sure to make your head and pedals spin. All of this is inspired by the resolute Texan’s shining example.

In his forthcoming autobiography, It’s Not About the Bike, Armstrong tells of receiving a visit from a worried friend on the eve of the penultimate stage of the 1999 Tour, a crash-prone time trial. Armstrong’s friend advised him to go easy, not to gamble his lead by pushing too hard.

The soon-to-be-champion was having none of it.

“I’m going to kick ass,” he replied. “I’m giving it everything. I’m going to put my signature on this Tour.”

And so he did.

Back Off

Steady Burn

LANCE ARMSTRONG HAS BUILT A CAREER OUT OF DEMOLISHING OUR EXPECTATIONS. When he entered the pro ranks in 1992 at age 21, the cycling press billed him as “the next Greg LeMond,” eliciting the famous retort, “No, I’m the first Lance Armstrong.” His victory in the Clasica San Sebastian in 1995 sent the competition a not-so-subtle message about his tenacity—three years earlier he’d finished dead-last in the very same race. And his victory in the 1999 Tour de France redefined what it meant to be a cancer survivor. (As did his nekkid appearance in Vanity Fair shortly thereafter.)

But while Armstrong’s triumph over his disease and his rivals made him a superstar, the training plan that got him there—the same one he’ll use to defend his Tour title this July—may prove to be an equally stirring story. It enabled him to pull off one of the greatest comebacks in all of sports (a saga detailed in his memoir, It’s Not About the Bike: My Journey Back to Life, to be published later this month by G.P. Putnam’s Sons), yet it tramples the underlying tenet of most every athletic training program, no pain, no gain.

And if professional road cycling is about anything, it’s pain. “The tried-and-true approach is to sink yourself in Europe and race yourself into condition,” say Chris Carmichael, Armstrong’s coach of ten years. Each season begins the same way: Starting in early February, you push yourself to utter exhaustion at a race every weekend, ride easy for several days to recover, and then do a maximum-effort ride midweek, only to race again a few days later. Physiologically, we’re talking repeated high-intensity anaerobic workouts—bludgeoning your body to increase its capacity for pain.

When Armstrong returned to racing in 1998 after sitting out a year to recuperate from his cancer treatments, he jumped right back into the charming conventions of the peloton. It quickly became clear, however, that he wasn’t recovering between races as he should. In early March, at Paris-Nice, the first important stage-race of the season, he abruptly dropped out on the first day. His explanation? “I decided that I didn’t like the sport at all and wanted to quit and go home to Austin forever.”

His dicouragement faded fast; this was a guy, after all, who had been world champion in 1993. Before long he was back on his bike and talking to Carmichael about his training. “What his quitting did was make us take a different approach,” the coach says. “We had to improvise.” Instead of doing loads of anaerobic work, they backed off and began focusing purely on Armstrong’s aerobic system. To that end he logged endless hours in the saddle, doing fairly low-intensity aerobic workouts. “What we found was his body was actually adapting better,” Carmichael says. “We cut back the racing, and by keeping him fresh, it allowed him to stay focused, to stay with his training.”

The ’98 season wsa still young. After taking stock, coach and cyclist decided to skip the Tour and peak for the World Championships in The Netherlands in October. The results were astonishing: Armstrong won several second-tier races in June and Jule and then took fourth at Worlds. The man was back.

RING OF FIRE

The key to power is pace

THE PERFECT CADENCE MAY BE LIKE THE HOLY GRAIL TO THE enlightened cyclist, but finding it should prove to be a helluva lot easier. Just follow the directions below from Chris Carmichael, Lance Armstrong’s coach.

You’ll need to equip yourself with a heart-rate monitor and a bike computer that records pedaling cadence. Lay out two three-mile time trials along a route in such a way that you’ll have 15 minutes to recover between them. Ride as fast a pace as you can maintain for the duration of each trial. If you can’t do the second TT at the same pace, then you’re probably exceeding your lactate threshold. The course, not incidentally, should be windless, flat, and without traffic lights, angry dogs, or other distractions. Do the first trial, spin easily to the next, and repeat.

Follow this drill once a week for three weeks, making sure to keep the workout consistent down to the smallest details. “Do the same warmup the same time each day, and eat the same foods,” say Carmichael. The only factor you want to vary is your cadence (shifting gears as necessary). Ride at 80 pedal revolutions per minute the first outing, 90 rpm the second, and 100 rpm the third. It’s fine if your cadence drifts above your target rpm, but don’t let it dip below the mark.

After each TT, record your time, as well as your average heart rate and cadence. The goal is to ratchet up your cadence ever higher until one of two things happens: your heart rate jumps five beats per minute or, alternatively, your ride takes an extra 15 seconds. So long as you haven’t hit these marks, you can and should boost your cadence. For example, if at 90 rpm you finish in six minutes with an average heart rate of 170, but at 100 rpm can tick off the same three miles in six minutes and ten seconds with a heart rate of 174, you’d do well to train at 100 rpm.

Be warned: Changing a factor as critical as cadence is as awkward as tweaking your running stride. But, as Arnstrong will attest, the payoff can be huge.—G.L.

Sit and Spin

The next step was to look at what it would take to tackle the Tour the following summer. Armstrong started training immediately after Worlds, doing six-hour rides at 90 rpm or more—a fast cadence and a fundamental change made at Carmichael’s behest. “Lance is a small rider, compared with Miguel Indurain,” says the coach, referring to the Spaniard who is the Tour’s only five-time consecutive champ (Armstrong is 5-foot-10 and weighs 158 pounds). “Indurain has larger muscle mass, meaning he can use bigger gears. Lance needed to break this work into smaller segments. It’s like lifting 300 pounds. If you’re a gorilla, you can lift it all at once, but if you’re a little guy, you’d be better off lifting 100 pounds three times. In Lance’s case, it meant he had to pedal faster.”

The old Armstrong pedaled at 75 to 80 rpm on climbs, while the new Armstrong spins at 85 to 90. (To figure your optimal cadence, see “Ring of Fire,” previous page.) According to the cyclist, “I completely changed my training by going high gears, always staying in the seat, never standing up on the climbs.” The idea, according to Carmichael, was to train his aerobic system to adapt by elevating his heart rate. “The Catch-22 is you have to breathe more,” he says. “It wasn’t just ‘Lance, you’re going to time-trial faster if you can pedal faster.’ We had to give him the aerobic system to do that.”

Specifically, that meant making sure that during the bulk of his training Armstrong is fueling his muscle-cell contractions with glucose and oxygen, a sustainable process that creates no nasty by-products. In contrast, pumping along anaerobically and firing muscle contractions with stored glycogen creates leg-searing lactic acid. Even if you could ignore the burn, you’d quickly deplete your muscles’ glycogen stores, which are finite. You simply cannot sustain anaerobic metabolism without adequate recovery, which is why racing predominately on aerobic energy offers an edge in the three-week-long Tour.

RAGE WITH THE MACHINE

What really counts is watts

Every time Lance Armstrong rides his bike, he’s on the clock. But in addition to logging his work hours he has to keep track of precisely how much effort he’s expending. Likewise, if you’re serious about wanting to crush your riding buddies, consider a gadget called the Tune Power-Tap Prologue, a souped-up bike computer-and-hub combo that costs a whopping $500.

It displays cyclometer functions such as speed and distance, along with heart rate and cadence, but what sets the Power-Tap apart is another metric: watts. Speed is a flaky indicator of effort because of variables like wind and road gradient; heart rate is iffy because it can fluctuate for the same effort depending on whether you went for the triple or the quad espresso. But watts are watts. A reading of your wattage is an absolute number that tells you precisely how hard your body is working.

While some stationary trainers will gauge watts, the Power-Tap (877-520-2179, ) lets you do it outside, on the bike you typically ride. Wondering whether that new aero front wheel really makes you faster? Slap it on your Power-Tap-equipped bike and see how many watts it takes to go, say, 20 mph. If it takes less power than it did with your old wheel, you’ve got yourself a winner.

The Power-Tap consists of a handlebar-mounted computer, a chest-strap to transmit heart rate, and a special rear hub that measures torque. You have to build the hub into a wheel, but don’t sweat it—any good shop can help you pick the right rim, spokes, and nipples and then assemble everything for you. Beyond that chore, setting up the Power-Tap is no more complicated than any other bike computer. The real work, come to think of it, starts when you hop on your newly outfitted bike. —G.L.

This Magic Moment

The good news is that you can train your body to go harder before your anaerobic turbo boost kicks in. First, you have to be able to identify the point at which your body switches from creating energy aerobically to creating it anaerobically—your lactate threshold. Most athletes use heart rate to gauge their effort. But in January of his winning season Armstrong started using watts, an absolute measure of power output. Unlike heart rate, watts are not affected by variables such as how much sleep or caffeine you’ve had. If you know that you’re pedaling along at 300 watts, you know exactly how hard you’re working.

In the lab, Carmichael pinpointed exactly how hard Armstrong could work the cranks, in watts, before his muscles began accumulating lactic acid. “Determining that benchmark is what’s critical for us,” Carmichael says. Back out on the road, with the number in hand, Carmichael could direct Armstrong’s training to elevate his lactate threshold. In addition, given that one can calculate precisely how much power it takes to pedal, say, a 12 percent grade at 14 miles per hour (the formula for watts is simple physics), Carmichael knows just how high Armstrong needs to boost that threshold to win.

“When you define what it takes to ride with the leaders of the Tour in the hills, given Lance’s body weight, it requires about 460 watts for 30 minutes,” he explains. “Before, let’s say 60 percent of Lance’s power came from his anaerobic system. He could stay with the leaders one or two days, but by the third day he’d be screwed from all the lactate.” Today’s Tour-conquering Texan culls a greater amount of his power from his aerobic system, accumulating less lactic acid over the course of a race, which in turn allows him to sustain higher outputs day after day.

Change Is Good

Lance Armstrong Signature Edition bicycle

Armstrong’s coach, it should be noted, is no physiologist. He bases the new program on the sheer experience of working with one extraordinarily devoted athlete for a decade, and luckily for the Tour champ, science appears to back up his coach. “Carmichael shows a remarkable understanding of physiology and how training affects Lance’s body,” says Jim Martin, an assistant professor in the department of exercise science at the University of South Carolina and an expert in muscle mechanics. Martin adds that part of Armstrong’s new aerobic efficiency could be attributed to a change in the composition of his muscle fiber. In a number of studies on laboratory animals, he notes, muscles that are repeatedly stimulated eventually become more efficient by converting fast-twitch fibers to slow-twitch fibers. (All things being equal, the more slow-twitch muscle fibers you have, the more power you can produce at the same oxygen consumption.) “There’s no evidence to show you can do this with training,” Martin admits. “But if human muscle remodels itself the way animal muscle does, then Lance’s sub-threshold work may be converting his leg muscles into more efficient powerhouses.”

By happy coincidence, this program has psychological benefits as well. “Most people who train just go out the door and start blasting away as hard as they can, but they can only go a little harder than lactate threshold,” Martin says. “They can’t go much harder than that for very long, and they won’t go below that because they don’t feel like they’re doing anything. But lactate threshold represents what you can already do—so it’s not much of a training stimulus.”

It’s a situation that Carmichael encounters all the time with new athletes he coaches, who feel at first like they aren’t working hard enough. His star pupil, of course, got over that long ago and has kept his attention on the finish line of the Tour ever since.

We’ve learned by now not to take anything for granted when it comes to Armstrong, but this we know for sure: To him, the Tour is more than just a 2,000-mile race around the French countryside. “There is no reason to attempt such a feat of idiocy, other than the fact that some people, which is to say some people like me, have a need to search the depths of their stamina for self-definition,” Armstrong writes in his forthcoming memoir. “But for reasons of my own, I think it may be the most gallant athletic endeavor in the world. To me, of course, it’s about living.”

Garrett Lai, who has been riding and racing road bikes in Southern California since he was 11, is the senior editor of Bicycling magazine.

PONY UP FOR THE ULTIMATE EGO TRIP

If you’re still searching for that perfect centerpiece to your Lance Armstrong shrine, consider this sacred icon: Trek (800-313-8735, ) is now offering a replica of Mr. Maillot Jaune‘s race bike. Dubbed the Lance Armstrong Signature Edition, it’s a $4,500 facsimile of the rig he rode in the 1999 Tour (except in the time trials), complete with his reproduced John Hancock emblazoned on the top tube. Built around Trek’s gossamer 2.4-pound carbon-fiber frame and matching carbon-fiber fork, it features a full complement of Shimano’s top-shelf Dura-Ace components as well as a snazzy pair of Rolf Vector Pro wheels. All that vibration-damping carbon fiber makes it feel as if you’re piloting a hovercraft over cracks and scars in the pavement.

Trek’s producing only 1,999 of these souvenirs. Should you miss out, you’ll be happy to note that for $1,800 less you can snag the Trek 5200—the very same frame furnished with lower-tier components. (The parts are perfectly good, but they raise the weight of the bike by all of one pound; it’s a feathery 19 pounds versus a ridiculous18.) And who knows, if you were to donate the difference in cash to the Lance Armstrong Foundation for cancer research (800-496-4402), you might just have a shot of getting the champ to sign your bike himself. —ERIC HAGERMAN

Here On Planet Granite

Cross-country: White Mountains, New Hampshire

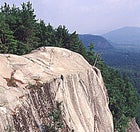

Cathedral Ledge

On the brink: edging along Cathedral Ledge

On the brink: edging along Cathedral LedgeKayakers scout rapids, climbers scout routes, and telemark skiers scout lines. Mountain bikers rely on momentum. Or at least that’s what I tell myself as I drop off a muddy knob roughly the size of a Volkswagen Beetle into a shallow stream of algae-slick babyheads three-quarters of the way up the Dickey Notch Trail. You know babyheads, the small, round granite boulders that litter trails throughout New Hampshire but are most prevalent in White Mountain National Forest, where I’m riding right now. Dry babyheads are no problem; a standard suspension fork will gobble them up like butter (“buttah” to a Yankee). Wet babyheads, though, are a big problem, especially when you hit them with momentum.

I should have scouted. My front tire slips off the first greasy skull, turns sideways, and wedges itself under the jawbone of greasy-skull number two, instantly terminating my bike’s momentum. My motion, however, continues. I gracefully breaststroke over the bars, click effortlessly out of my pedals, and auger my face and shoulders into the mud of the opposite bank—a process referred to in mountain-biking circles as “taking a soil sample.”

With blackflies feasting on the back of my neck, and the bones in my shoulders slowly squirming back into their sockets, I realize why I love riding in the Whites: It’s a constant challenge. Wide-open Western terrain allows riders to take their eyes off the trail and gaze dreamily at wildflower meadows. Try that in the dense hardwood forests of central New Hampshire’s White Mountains and you’ll be gazing dreamily under heavy anesthesia at the surgeon trying to salvage what’s left of your spleen. (Two local off-roading brothers I know have broken six collarbones between them.) It’s the only place I’ve ridden where it’s common to crash on the way up; climbs are relentless white-knuckle grunts up loose pitches spiderwebbed with roots that never seem to dry. If your front tire isn’t perfectly square when you hit one, you’ll go down mousetrap-fast. Descents tend to track straight down because New Hampshire soil is so rock-infested that it’s nearly impossible to carve switchbacks into the hills.

The U.S. Forest Service estimates that there are 700 miles of bikeable trails in this 1,250-square-mile backcountry, part of a massive system of single- and doubletracks between Plymouth to the southwest and Conway to the northeast. But the best rides in the forest are in the Pemigewasset Ranger District just north of Plymouth. Short sections of dirt roads connect trails that usually wind through notches, New Englandspeak for narrow valleys or passes. And even though this wooded nexus is just two hours north of Boston, seeing any people at all among the white pine, paper birch, and sugar maple is a rarity. Hikers prefer the steep, open granite of the higher peaks, terrain that mountain bikers usually avoid because it involves long hike-a-bike sections.

A word of caution: Ridge rides that gain elevation rapidly tend to be extremely technical and grueling. A seven-mile loop on such terrain may take as long as two hours and always leaves one bruised, bloodied, and bonked. It’s such a rugged topography that equestrians generally don’t bother. “You could probably pack a horse in,” a friend once explained to me, “but you’ll pack out the meat.”

Prostrate among the babyheads, feeling as though my meat is already half-packed, I crawl to my knees and drag my bike out of the ditch. Within ten revolutions, momentum returns and carries me, dependably, on up the trail. Maybe I’ll try a different line tomorrow.

The Dirt: The regional Forest Service (603-536-3373), which oversees WMNF, welcomes mountain bikers, and even produces a map of the Pemigewasset’s most popular rides ($4; 603-744-9165), including the Dickey Notch Trail. Parking passes are required at WMNF trailheads: $7 buys a seven-day pass; $20 covers your car for the year. Order one a few weeks before you go, or stop in any U.S. Forest Service office and buy one.

Cannondale F900 SX

VITALS: $2,700; 800-245-3872;

WEIGHT: 3.8 pounds frame, 25.4 pounds complete

FRAME: Butted, oversize aluminum tubes

FORK: Long-travel single-sided Lefty DLR (100mm of travel)

COMPONENT HIGHLIGHTS: Coda Expert Disc Brakes for antilock, wet-weather stopping THE RIDE: If you aren’t keen on getting eaten alive on tight root-and-rock-infested East Coast singletrack, you’ll want a hardtail with short overall measurements for quick steering and a high bottom bracket to clear all those bony obstacles. The F900 SX fits the bill. But what’s with that freaky fork? Conventional long-travel shocks would be the last thing you’d want here because they’re heavy and they pogo on climbs. The Lefty is a long-travel design that works, saving weight by amputating a leg and fighting pogo with a lockout lever that you can turn while riding. Lock the suspension for climbing, open it for descending, or leave it half-cocked for rollercoastering. The F900 SX also has a suspension seatpost, which helps you stay seated on technical climbs.

LITESPEED TANASI

VITALS: $2,800 (frame only); 423-238-5530;

WEIGHT: 3.1 pounds

FRAME: Rare, light, and strong 6AL/4V titanium tubes

FORK: Featherweight, air-sprung RockShox SID SL Race (63 or 80mm of travel)

THE RIDE: Titanium has a dirty little secret, and it is this: The stuff can act seriously spongy when you pour on the power. To eliminate any frame flex in their new Tanasi, the Ti-meisters at Litespeed have transformed its round tubes into laterally stronger shapes—squarish for the downtube and decagonal for the seat tube. This is no small achievement considering that those tubes are a 6AL/4V alloy, which is stronger and lighter than the 3AL/2.5V stock used in “cheap” Ti bikes but very difficult to manipulate. Litespeed’s own little secret is “cold-working” the tubes—carving and cutting them at temperatures that are far below normal, eliminating the use of excessive heat, which weakens the metal. So much painstaking work results in a frame that won’t cower under hard pedaling yet that maintains titanium’s trademark comfort. All of which makes the Tanasi easily worth the extra two grand. Right, honey? —ANDREW JUSKAITIS

Blacktop Beauty

Road Riding: Madison, Wisconsin

It’s the cows.

These three words have become the standard, slightly wry explanation for why there are so many sleekly paved roads in the 35-mile radius surrounding Madison, Wisconsin—hundreds and hundreds of winding miles of ’em. This is the Dairy State, after all, and milk is money; washouts, deep mud, and other excuses for missing the daily udder-to-market runs are unacceptable to farmfolk. Hence the flawless blacktop and attendant roadies. The cows, quite simply, have made Madison the unassailable nucleus of Midwestern road riding.

During the summer months, after spring rains have washed the salt from the asphalt, it’s not uncommon to see a paceline descend a twisting dairy road at 50 miles per hour, apparently without fear of potholes. And on weekends, the Madison-based 300-member Bombay Bicycle Club leads a peloton into the rippling pasturelands to hills like the Pinnacle, a climb with an 11 percent grade that tops out with a 360-degree view of the Holstein-dotted valleys below.

You probably wouldn’t expect hills to pucker up so steeply in these parts, but near Madison, they do. The last glacier to steamroll the Upper Midwest missed southwestern Wisconsin, leaving sweeping ridges that look more Catskill than flatland. Here there are climbs of 1,000 feet in less than a mile, sublime vistas of blue-gray escarpments, and corkscrew drops—all on roads so lightly traveled as to be almost empty.

Madison itself (population 200,000) is home to a strident Small-Is-Beautiful counterculture that has promulgated the cycling life by adding bike lanes on all major roads, opening bike shops (a dozen in and around town), forming 12 or so cycling clubs like Bombay, and hosting over 20 bike-related events each year. But the best riding is in the outskirts, near the old Norwegian town of Stoughton, 25 miles south of Madison. Phil Caravello, a 35-year-old local road racer who owns the town’s only bike shop, Stoton Cycle, is happy to give you a map of his favorite route, the Dunn This Tour, a 30-miler past red barns and green hillocks and through towns no bigger than ten revolutions of your wheels. Phil also organizes an informal weekly Thursday evening ride of 20 to 30 miles (sign sprints— between town line signs—are optional) that ends with micro-brews in the alley behind his shop.

Or forget the group, as I often do, and take a crack at the solo equation: just you, your bike, and the quiet chewing of cud. Every April, the lure of the hills works its magic on my muscles and I ride, venturing farther and farther afield on my beloved Bianchi, until one day I find myself hitting the drop bars and pushing the big ring down the beautiful, unblemished Wisconsin pavement, past fields of Holsteins that leave me reverential. You gotta love those cows.

The Dirt: The solo pedaler should refer to Milwaukee Map Service Inc.’s road map of southwestern Wisconsin ($6; 800-525-3822); it shows every farm road, dead end, and possum trot in remarkable detail. For group rides, call Bombay Bicycle Club (608-274-1886) or hook up with Phil Caravello at Stoton Cycle (608-877-1134). Road-bike rentals are scarce, so you’ll want to BYOB. If you’re feeling especially fit, sign up for Bombay Bicycle Club’s Wright Stuff Century Ride on September 4, which passes Taliesin, home of the late architect Frank Lloyd Wright.

SCHWINN PELOTON

VITALS: $1,630; 800-724-9466;

WEIGHT: 3.8 pounds frame, 19.6 pounds complete

FRAME: Schwinn’s chrome-moly tube set

FORK: Carbon-fiber Time Club

COMPONENT HIGHLIGHTS: A complete group of workmanlike Shimano 105 parts, including brake-lever shifters and lightweight Speedplay X3 pedals

THE RIDE: Nothing stands out as remarkably new here, but that’s just fine: The Peloton incorporates classic angles and frame materials. Unfortunately, the classic lugged construction method preferred by retrograde roadies—joining the tubes with ornate metal sleeves—is expensive, so Schwinn opted for TIG welding. Still, the Peloton possesses the same angles and quality steel tubing of the more expensive and beloved Paramount frame. Not that you or I could tell the difference—the ride quality is almost identical. A low bottom bracket promotes aggressive cornering and handling by positioning the rider’s center of gravity closer to the ground—all the better to see the pavement streaking by underneath.

SEVEN CYCLES AXIOM TI

VITALS: $2,595 (frame only); 617-923-7774;

WEIGHT: 2.7 pounds

FRAME: Hand-crafted 3AL/2.5V butted titanium tubes custom-built to match your measurements

THE RIDE: Cursed with long legs and a short torso like T. rex? No problem. The artisans at Seven will shorten the top tube so you can reach the drop bars in comfort. Created on the premise that a bike should fit like a custom suit, Seven Cycles can build a bike tailored to the sideshow freak in us all. And nowhere is a perfect fit more important than on pavement, where you spend long hours in a relatively static position, which makes the Axiom Ti quite the dream ride. Aside from size, the folks at Seven also handpick the diameter, thickness, and profile of the tubes—they claim to have infinite options available—to match your style of riding. To top things off, the Axiom’s seat stays are bent to absorb road shock, and the chainstays are bent to allow ample heel clearance. It’s about as close to perfect as you can get. —A.J.

Gravity’s Rainbow

Downhill: Sun Valley

Adams Gulch in Sun Valley

What goes up: descending Adams Gulch in Sun Valley

What goes up: descending Adams Gulch in Sun ValleyDrop off Bald Mountain’s 9,150-foot summit, plunge 3,400 vertical feet in ten miles on buffed western singletrack through sagebrush and pine, and you’ll realize why Sun Valley is fast becoming the downhill destination of choice. This place is all about speed. Unlike California’s Mammoth, a lift-served hot spot since the first Kamikaze Downhill race in 1985 and celebrated for fire roads covered in ankle-deep pumice, the trails on Sun Valley Resort’s Bald Mountain are hard packed, which means you can lay the bike over in corners and lay off the brakes in straightaways. Which means you can go fast. And fast, apparently, has its allure—at least to the estimated 4,000 riders who sampled the high-speed quad-accessed dirt during last year’s 98-day season.

Yet even on a “busy” summer day, riders are so spread out on Bald Mountain that it’s possible to experience a sense of utter seclusion. Consider it your own private Idaho—albeit one with water bars that double as launchpads on singletrack just three years old, perfect for heavily padded downhill racers on long-travel suspension bikes. Riders like local speed demon Clint Jones, a 30-year-old former motocross racer who routinely hits close to 45 mph while training for downhill bike races. Tag along with Jones and you’ll quickly discover another Bald Mountain bonus: No bike cops. (Beware the occasional biker and hiker.)

If you’re not ready for high velocity, take the mountain at your own pace on the moderate pitches of the Cold Springs and Warm Springs Trails. But do be sure to keep your pace in check: A wrong move at speed on Warm Spring’s 11.2-mile lodgepole slalom course could leave you emulating Wile E. Coyote or dangling upside down with your cleats still clipped in.

The Dirt: Lift fees are $14 for a single ride, $22 for a full day. For more information, call Sun Valley Ski Resort at 800-322-3432 or visit . Full-suspension bikes (four- to five-inch travel on shocks) are available for rental at the base of Bald Mountain next to the River Run Lodge for $35 per day.

KONA STAB PRIMO

VITALS: $5,000; 800-566-2872;

WEIGHT: 9 pounds frame, 48.5 pounds complete

FRAME: Oversize-aluminum-tubed rig with motorcycle-size rear swing-arm that provides upward of nine inches of travel

FORK: Marzocchi Monster T (7 inches of travel)

COMPONENT HIGHLIGHTS: Where to begin? Downright obese Nokian Gazzalodi DH tires, impact-resistant Race Face cranks, and foolproof downhill-specific Hayes disc brakes.

THE RIDE: With only enough gears for “fast” and “insanely fast” (there’s just one chainring in front, and it’s a big’un), this pig can be ridden in only one direction: down. Fully loaded right out of the showroom, the Stab Primo does its one task very well. It better, because you’ll need a chairlift or a truck to get it uphill. Once you’re there, hang on: The Stab’s suspension soaks up rocks, water bars, and small woodland creatures so smoothly that in three or four thunderous heartbeats you’ll be rounding corners at 40 mph. In fact, at speeds less than 30 mph the Stab is fairly unwieldy; good luck bunny-hopping logs on a 50-pounder without a full head of steam. For $5,000 you’d think they’d throw in some pads or a coupon for a free visit to your local emergency room, but it’s still cheaper than piecing together a custom downhill rig.

INTENSE M1-SL

VITALS: $2,750 (frame only); 909-678-4576;

WEIGHT: 8 pounds

FRAME: Heat-treated 6000 series aluminum monocoque with 8 inches of state-of-the-downhill-art travel

THE RIDE: With more U.S. podium visits than any other bike, the M1-SL defined the way gravity-dependent machines are built. (Competing teams have been known to purchase frames and disguise them with different paint jobs.) In addition to its monster-truck suspension, the M1-SL features unheard-of adjustability. Lower the bottom bracket height for the most stable center of gravity that conditions allow; incline the head tube angle for quicker handling on technical courses; extend the wheelbase for better tracking on faster slopes. The possibilities are endless. Indeed, riders in Vancouver are reportedly piloting their MI-SLs off of 32-foot cliffs. Yet it devours high-speed stutter bumps. Assemble it with the right parts and you could get it down to 38 pounds (the total price might be in the neighborhood of $6,500). Still, it’s probably best to hold off on the purchase until you’ve actually made the team.—ANDREW JUSKAITIS

Take the Express Lane

Track Cycling: Trexlertown, Pennsylvania

Lehigh Valley Velodrome

Race day at the Lehigh Valley Velodrome

Race day at the Lehigh Valley VelodromeIt was as a member of the 1968 U.S. Olympic skeet-shooting team at the Mexico City Games that millionaire magazine publisher Bob Rodale caught his first glimpse of a velodrome. “What a beautiful sport cycling is,” he would tell a reporter. “Almost like a dance.” Eight years later, still charmed, Rodale became a patron of the sport by financing the construction of the country’s tenth velodrome, in Trexlertown, Pennsylvania, not far from his Rodale Press headquarters. He commissioned the 333.33-meter track with extra-wide lanes and long turns, and laid its surface with Chem-Comp, faster stuff than traditional concrete—making it the most innovative velodrome in the country. Track cycling, in which riders on brakeless, single-gear bicycles careen around a steeply banked oval at upwards of 30 miles per hour, experienced its heyday in the early decades of the 20th century; the country went from having hundreds of wooden velodromes to none by the end of World War II. Since then it hasn’t exactly been a mainstream sport—perhaps in part because, to slow down, you have to apply backward pressure on the pedals or risk running headfirst into a wall. Even so, the day the Lehigh Valley Velodrome opened, 100 cyclists showed up to ride.

In 1976, T-Town’s speed course became a training ground for international Olympic track cyclists en route to the Montreal Summer Games. Today there are 20 such tracks in the United States, but Lehigh continues to nurture a disproportionate number of cycling champions—1988 Olympian Dave Lettieri and 1992 Olympian James Carney started out here—thanks largely to a free-for-the-public cycling program sponsored by local chemical company Air Products. The current buzz centers around T-Town native Marty Nothstein, 29, the silver medalist in the 1996 Olympic match sprint (a three-lap cat-and-mouse event that ends in a neck-whipping burst of speed) who’s considered to be a shoo-in for the U.S. team in Sydney.

T-town’s Olympic spirit will hit its peak this June, when the velodrome is scheduled to host a pre-Sydney sprint camp for top riders from New Zealand, Canada, Australia, and the U.S. Nearly the whole town turns out to watch pro-level racers—including local hero Nothstein—spin their bikes around the 28-degree banks. But this is an equal-opportunity course, and the excitement extends beyond elite athletes: Licensed U.S. Cycling Federation track riders can race T-Town themselves on Fridays, and neophytes can sign up for free, three-weekend-long clinics offered throughout the summer. Cyclists who discover they prefer road over track can join one of the many local training rides put on by the Lehigh Valley Wheelmen’s Association—enough two-wheeling to give recreational riders gold-medal fever.

The Dirt: Trexlertown is located eight miles west of Allentown, just off Pennsylvania 78 and the Pennsylvania Turnpike—an hour from Philadelphia and 90 minutes from N.Y.C. Check out the velodrome’s Web site, , for schedules and fees (610-967-7587).

GT GTB-1

VITALS: $761; 888-482-4537;

WEIGHT: 3.4 pounds frame, 19.2 pounds complete

FRAME: Chrome-moly steel

FORK: Chrome-moly steel

COMPONENT HIGHLIGHTS: Super-smooth Suzue hubs

THE RIDE: GT’s patented Triple Triangle design, which overlaps the seatstays with the seat tube (creating the third triangle), results in one of one of the stiffest production frames on the market. That’s exactly what you want in a track bike, since velodromes have roller-rink-smooth surfaces and there’s no need for your frame to have a forgiving ride. And considering the size of the average track cyclist’s quads, the stiffer the bike, the better. The GTB-1 is the vélocipède de rigueur of both aspiring track racers and the baddest of Big Apple bike messengers, who dig its spartan componentry. No brakes, no shifters—no way some thief is going to successfully make off with this bike.

LAND SHARK TRACK SHARK

VITALS: $1,400 (frame only); 541-535-4516

WEIGHT: 4 pounds

FRAME: The choicest steel cuts from Reynolds or Columbus

FORK: Chrome-moly steel

THE RIDE: Master welder and spray-paint artist John Slawta, who lives in Ashland, Oregon, configures your choice of high-end tubing to take advantage of your strengths. Are you the muscle-bound type inclined to bursts of out-of-the-saddle sprinting? Ask Slawta to build the main frame from Reynolds 853 tubing, which is heavier and stiffer than the other options and so won’t noodle around under your efforts. More of a finesse rider? Slawta will likely recommend a lighter frame crafted from Dedacciai Uno tubing. Regardless, rest assured that your frame won’t come apart at the seams: Slawta joins the tubes by means of the classic art of fillet-brazing, a time-consuming process that ensures foolproof bonds. When the metalwork is complete, Slawta hand-paints his masterpiece, ensuring your new bike, like Slawta himself, is one of a kind. —ANDREW JUSKAITIS

Slog Heaven

Swamp thing: sea of mud at the North Sea-Tac Course

North Sea-Tac Course

Swamp thing: sea of mud at the North Sea-Tac Course

Swamp thing: sea of mud at the North Sea-Tac CourseNasty weather, frigid temperatures, and a face caked with mud are three reasons why cyclocross racing is, and will always be, a niche sport. Yet in Seattle, where 36 inches of annual rainfall make foul-weather riding a fact of life for the serious cyclist, necessity and obsession give it mass appeal. “If you must ride, then you must adapt,” intones Tim Rutledge, 41, a local two-time national masters cyclocross champion. Every Sunday from October to December, Rutledge and some 180 other willing victims—many of whom race the modified road bikes to stay in shape during mountain-bike racing’s off-season—happily hurdle barriers, slide down rain-eroded steeps, and shoulder their bikes through quagmires of signature Seattle mud on the mile-long obstacle courses.

But for the rest of us, cyclocross needn’t be so extreme. You can ride your rig year-round on mountain-bike trails (you don’t need us to tell you how to find them) and cyclocross courses, of which the Seattle area has more than its share. There’s the Stelacom Park in Tacoma, where you’ll tackle steep, sandy runs; and Olympia’s Thurston Fairgrounds, a flat, fast track that snakes through a barn and some horse stalls—great for speed training. Just five minutes from the airport, the North Sea-Tac Course (host to the 1994 and 1996 national championships) corkscrews up and down grassy, gravelly hills that turn to soup after a good rain. At the other end of the runway, the South Sea-Tac track tests riders with long stretches of heavy sand notorious for sucking wheels to a standstill.

The Dirt: All four Seattle-area courses are open year-round. (For information, call 206-675-1424.) There’s no fee to ride, but there is a $15 charge to race on Sundays. Gregg’s Greenlake Cycle (206-523-1822) will be happy to fenderize your bike for rainy-day rides.

VOODOO WAZOO

VITALS: $1,416; 800-739-1900;

WEIGHT: 3.6 pounds frame, 19.1 pounds complete

FRAME: Handmade heat-treated Columbus chrome-moly steel

FORK: Kinesis aluminum

COMPONENT HIGHLIGHTS: Mudophilic Time Atac Carbon pedals

THE RIDE: True, cyclocross bikes are fast on pavement and dirt, but if you’re actually planning to get your new bike dirty it better be durable as well. Traditionally, riders bought stock ‘cross bikes and replaced weaker road parts with mountain components as they broke—an expensive and frustrating approach. No more. Log on to Voodoo’s interactive Web site and assemble your Wazoo right the first time without the expense that goes along with a custom bike. However you trick it out, the Wazoo’s lightweight steel frame absorbs the harshest of rocky descents without compromising lateral rigidity for sprinting. Too bad you don’t have any choice about the aluminum fork, which transmits every bump and thump directly to your forearms. As if the sport wasn’t brutal enough.

INDEPENDENT FABRICATION

VITALS: $1,295 (frame and fork); 617-666-3609;

WEIGHT: 3.8 pounds frame only

FRAME: Hand-crafted chrome-moly steel constructed of a custom mix of lightweight Reynolds and True Temper tubing

FORK: Italian Deddacciai Uno steel

THE RIDE: There’s hand-built and then there’s hand-crafted. The former simply means that a person has welded together a set of tubes, but the latter means that after the initial work is done someone painstakingly finish-miters every junction, machines the bottom-bracket shell for perfect installation, and seals the tubes to keep out moisture. Independent Fabrication’s bikes are hand-crafted, which is particularly important in the case of its Planet Cross because the very elements that make cyclocross so much, well, fun—rain, snow, road salt—eventually eat most steel bikes from the inside out. Designed with an extra-tall head tube for plenty of shouldering room while portaging and bridgeless chainstays for extra tire clearance in muddy conditions, the Planet Cross has been ridden to both national and world championships. Your performance may vary. —ANDREW JUSKAITIS

Get a Grip

Tread design demystified (it’s not you, it’s the tires)

In a perfect world, the Volvo/Cannondale mountain-bike team’s support van meets you at the trailhead. Chief mechanic Dave Arnauckas hops out with an armful of new tires at the same time World Champion downhiller Anne-Caroline Chausson, having just inspected your trail, pedals up. A quick discussion ensues and in a blur of skilled motion Arnauckas swaps out your ratty treads for a pair perfectly suited to the conditions. Five minutes later you’re cranking up pitches you typically hike, lugeing down sections that usually send you cartwheeling.

“Bikes don’t come stocked with tires designed to work in every area of the country,” Arnauckas explains. “Tire selection on a muddy day can be the difference between two hours spent walking or two hours spent riding.” Likewise for sand, roots, and rocks. Put simply, picking the right tires will keep you on your bike and off your feet—or your chin. The idea is to balance traction and speed, both of which are functions of the size, shape, and pattern of a tire’s knobs, or lugs. Big, widely spaced lugs offer superior traction, but they slow you down. Short, tightly spaced lugs have less rolling resistance, but they leave you wallowing in mud. Know your knobs, and you’ll master your terrain.

That is, assuming you also know your tire pressure. Too much will make the plushest full-suspension rig ping all over the trail; too little will render the stiffest aluminum hardtail as sluggish as a vintage beach cruiser. “Try to find that fine line,” advises Arnauckas, “between something that will roll fast but still stay in good contact with the ground.”

As for determining a tire’s lifespan, you’ll just have to watch for wear. First check the braking edges—the sides of the lugs closest to you as you look down from the saddle. On the rear tire, eyeball the opposite edges of the lugs, which grip the trail. And be sure to inspect the lugs along the tire’s edges. “If the cornering knobs are worn,” says Arnauckas, “when you lay your bike over you’ll wash out. That wouldn’t be good.”

Of course, Volvo/Cannondale racers use tires for no more than a week, but that’s the luxury of getting them free from Hutchinson. You, on the other hand, will have to pay. As a non-sponsored duffer, though, at least you’re free to choose any model you want. That’s why we called upon riders from reputable shops in seven core mountain-biking spots to recommend the best tires for their terrain. The following picks are only suggestions; consider buying a second pair for spells of unusual weather. And remember that tire selection, like mountain-biking itself, is not an exact science. That’s what keeps it interesting.

NORTHEAST

MICHELIN WILDGRIPPER COMP 1.9

520 grams

($40; 800-346-4098)

For the technical riding over mud, roots, and rocks endemic to New England, Slade Warner, co-owner of Rhino Bike Works in Plymouth, New Hampshire, uses this light, zippy, and très French tire on both wheels. Other cross-country treads, with their clusters of short knobs, bog down in loamy soil, yet deep-lugged models are no better because they roll about as smoothly as paddlewheels on the dirt roads that link trails. Warner says mud just doesn’t stick to Michelin’s gaudy green rubber compound, thus leaving the WildGripper Comp’s treads free to grip. “When you get up to speed,” he says, “centrifugal force just blows the mud right off the back.”

SOUTHEAST

SPECIALIZED DIRT CONTROL COMP 1.9, TEAM MASTER COMP 1.9

front: 520 grams; rear: 620 grams

($35 apiece; 408-779-6229)

Mike Rice, head mechanic at River City Bicycles in Chattanooga, Tennessee, figures there must be between 700 and 1,000 miles of prime off-road riding in the area. Trails tend to run along ridges that drain quickly, leaving a surface of bony hardpack, which would be fine if it weren’t for the countless stream crossings and fallen logs. It’s too solid for mud tires and too technical for slicks. So Rice recommends the Dirt Control Comp up front, and the Team Master Comp in back, which balance speed and traction. The Dirt Control’s short triangular lugs point in the direction of the rotation, which reduces rolling resistance and helps the tire track straight, yet stops quickly because the braking edges hit the turf squarely. In back, the Team Master’s midsize lugs and its square profile provide solid bite on bark-stripped logs and creek banks.

MIDWEST

PANARACER FIRE XC PRO 2.1

560 grams

($36; 510-790-2967)

The upper peninsula of Michigan is veined with subalpine singletrack that dips and rolls through the woods. It’s a little rooty, a little mossy, rarely muddy—a mild recipe that would call for skinny semi-slicks, save for the frequent pockets of deep sand. To float over them, sales manager Shane Whyatt of Brick Wheels in Traverse City recommends the Fire XC Pro. “The interrupted center lug pattern on the Fires gives good bite in sand, but because the lugs are short there isn’t much rolling resistance,” he explains. The tight pattern of uniform block-shaped knobs works for both the front and rear.

ROCKY MOUNTAIN WEST

WILDERNESS TRAIL BIKES VELOCIRAPTORS

front and rear: 670 grams

($39 apiece; 415-389-5040)

“It won’t rain for two months and then it will rain every day for six weeks,” says Klaus Kracht of the weather in Crested Butte, Colorado, where he owns the bike shop Alternative Sports. “The trails go from moon dust to liquid black mud. You need a tire that can handle a variety of conditions.” In the Butte, where granny gear climbs last upwards of three hours, and where you’re likely to encounter any of the above conditions on any given ride, that’d be the VelociRaptors. Hit a section of silt at 12,000 feet on a climb and you’ll be glad WTB didn’t skimp on the size of the beveled blocks studding the rear tire—they will not slip. On the downhills, the big, widely spaced cornering knobs cut through deep dust, greasy mud, or loose talus. They’re a little heavy and knobby for spinning along on roads, but the Rockies are all about singletrack anyway.

SOUTHWEST

GEAX SEDONA 2.25

659 grams

($37; 800-350-0688)

Moab may be famous for the Slickrock Trail, but when you venture off this theme-park route you’ll need tires that can handle both sandstone and its post-erosion sibling, plain ol’ sand. For that, bike mechanic Joan Martocello and the rest of the crew at Poison Spider Bicycles ride the chubby Sedona. “The rubber on the Sedona adheres to the sandstone real well, but the lugs are short enough that they don’t shear off,” says Martocello. As for its performance in sand, the Sedona’s sparse pattern of sickle-shaped lugs, combined with its raftlike 2.25-inch-wide profile, let it float over the deep stuff like a Lunar Lander.

CALIFORNIA DOWNHILL

TIOGA FACTORY DH 2.3 FACTORY DH 2.1

front: 900 grams; rear: 800 grams

($50 apiece; 888-468-4642)

Downhill racing as we know it started at Mammoth Mountain, California, on the Kamikaze course, and the scene is still all about speed. Whether you’re riding the lifts at the ski resort or running your own shuttles on the 13-mile Lower Rock Creek Downhill, take the advice of the so-called freeriders at Mammoth Sporting Goods and go big—as big as your full-suspension frame will accommodate. To cut through the pea-size pumice that litters most trails, they suggest the Factory DH in the massive 2.3-inch width up front and a 2.1-inch in back. (Don’t judge these knobbies strictly by their numbers; even the 2.1 dwarfs every last tire on these pages.) Extra-thick nylon cords in the casing enable them to withstand big hits and make them virtually immune to pinch flats. And the quarter-inch-tall lugs make your bicycle look like a motorcycle.

NORTHWEST

IRC MUD MAD 1.95

front and rear: 550 grams

($30 apiece; 510-441-0126)

As the service manager at Portland’s Fat Tire Farm, not to mention a former amateur state champion in both cross-country (Texas) and downhill (Oregon), Butch Wells speaks of mud like Smilla speaks of snow. “It rains eight months a year out here,” he says. “There’s that muddy runoff that doesn’t stick to your tires but gets you real dirty and makes the surface slick, and then there’s that nasty clay that instantly clogs tires.” For a pure mudder that can handle these extremes as well as every earthen viscosity in between, Wells recommends the Mud Mad, which comes in separate tread patterns for the front and rear wheels. Both tires have deep, conical lugs that grip like a colony of leeches but are spaced well-enough apart to shed even the most adhesive quag with ease. Best of all, the Mud Mad’s sub-two-inch width slices right through surface slop to hook up solidly with terra firma—such as it may be.

Do the Javelina

Desert Riding: Tucson, Arizona

Santa Catalina Mountains

Streaking past saguaros on the 50-Year Trail in the Santa Catalina Mountains

Streaking past saguaros on the 50-Year Trail in the Santa Catalina MountainsNot all Sonoran desert mountain-biking hazards have needles, as I was reminded on a recent ride. I was peeling down a stretch of craggy Tucson Mountain singletrack, my mind so focused on avoiding the flesh-tearing saguaro cacti that I didn’t notice a pack of javelinas (snouted, piglike beasts about as tall as a tire) milling around the arroyo at the bottom of a hill. Seconds from impact, I hiked my feet high above the top tube and flew into the middle of the bifurcated herd, sending panicked javvies leaping left and right like flumes of parted water. They shrieked; I shrilled. When at last I stopped and looked back, the biggest of the bunch stamped a hairy hoof, and I beat a retreat, leaving their indignant porcine faces in the dust as I wheeled off down the trail.

Cactus-cruising around Tucson isn’t just about dodging obstacles. Sure there are chollas and rattlers, but there’s also serene beauty. Head up to the granite-strewn trails of the 20,000-acre Tucson Mountain Park (just a 20-minute ride from town) at sunrise and you’ll see what I mean. I’ve lived here all my life, but I never tire of watching the Sonoran Desert morph from pink to gold to ocher, or the phantasmagorical cactus-shadow show cast on rock mounds. Part of a 26-mile network of paths, the seven-mile, javelina-heavy Yetman Trail in the northeast corner of the park is one of my early-morning favorites; in addition to guaranteed wildlife encounters, including coyote and red-tailed hawk, the beginner-friendly web of double- and singletrack sweeps over exposed rock, around 20-foot saguaros, down arroyos, and through sandy stretches of parched emptiness.

Or throw your bike on a rack and head to Catalina State Park, 17 miles north of Tucson, where technically superior riders can tackle the 50-Year Trail, an out-and-back route named for a half-century land lease that protects it from development. Red, hard-packed double- and singletrack twist through an ocotillo-studded landscape where granite rocks are jumbled up in unearthly formations. You’ll need some quad power to crank up the steeper climbs, but once you make it to the extreme north end of the 18-mile trail, at the foot of the ragged Santa Catalina Mountains, you’ll be rewarded with spectacular views of the canyon-cut Oro Valley. And if, like me, you embrace your inner masochist, seek out the technical Deer Camp Loop (the folks at Full Cycle, the largest bike shop in Tucson, can provide directions), a locally prized ring of unmarked singletrack just off the 50-Year where sharp rocks jut from the desert floor on steep climbs, just waiting to trip you up and send you reeling into the outstretched limbs of a particularly prickly patch of desert flora—or fauna, as the case may be.

The Dirt: To familiarize yourself with the near-limitless riding options in the region, pick up Map-Trails of the Tucson Area at Full Cycle($12, 520-327-3232), where you can rent both hardtails ($25 per day) and full-suspension bikes ($45). You can ride to Tucson Mountain Park (520-740-2680) from town, but you’ll need a vehicle to reach Catalina State Park (520-628-5798). Wherever you ride, remember that this is the desert: Summer temperatures can climb into the hundreds, so get an early start, or better yet, ride in spring or fall.

Giant XTC DS/1

VITALS: $1,875; 800-874-468;

WEIGHT: 4.2 pounds frame (including rear shock), 26.8 pounds complete

FRAME: Super-lightweight aluminum-tubed four-bar linkage design with air-sprung RockShox SID rear shock (3.75 inches of travel)

FORK: RockShox SID air (80mm of travel)

COMPONENT HIGHLIGHTS: Light and strong Race Face Prodigy cranks and powerful Hayes disc brakes

THE RIDE: Out West, where the terrain is relatively smooth and fast, riders have often grudgingly traded precise handling at slow speeds for the high-speed control of full-suspension rigs. With the Giant XTC DS-1, they no longer have to compromise. When you’re in the saddle hammering, the XTC doesn’t bob, yet it still soaks up moderate impacts with zeal. It accomplishes this with a design that positions the pivots so that pedaling doesn’t activate the suspension. The rear shock hovers patiently, waiting to soak up the worst hits a trail can dish out. Even though the XTC—like all full-suspension bikes—still pogos when you stand up to sprint, it has the least bob for the buck of any bike to date. Not to say $1,875 is cheap, but given that a full-suspension frame of this caliber would cost $1,600 without a single component, the XTC is a bargain.

TURNER O2

VITALS: $1,995 (frame only); 909-696-9143;

WEIGHT: 5.5 pounds

FRAME: Lightweight aluminum hand-crafted by suspension guru David Turner, and a lightweight air-sprung Fox rear shock (3.1 inches of wheel travel)

THE RIDE: David Turner perfected his craft working with Horst Leitner, originator of the Horst Link, which allows four-bar linkage suspension to work so well. Turner’s frames blend that modern-day technology with the very best in Old World craftsmanship. Run your fingers over the beautiful TIG welds. Take note of how easily the rear wheel slips into the dropouts. Scan the length of the down tube and notice how the rear wheel is perfectly centered. That’s Turner making sure each bike that leaves his shop in Eagle, Colorado, is arrow-straight. The best part about the O2 isn’t how it looks, but how it climbs. The back tire hooks up tenaciously on rough terrain, while the steepish head and seat angles keep your weight forward as the ascent gets vertical. The O2’s steepish price rewards Turner for all his hard work. Place your order now and maybe you’ll see your bike in July. —ANDREW JUSKAITIS