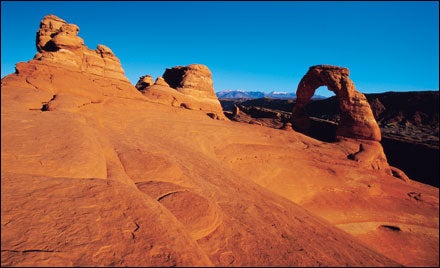

ABOUT 10,000 YEARS ago, some Indians found a sweet little piece of ground in the red-rock desert. They drew pictographs, snacked on antelope, and camped out a while but generally left the scenery intact. Centuries passed with little disturbance except for Manifest Destiny and the wind. Then, in 1929, President Hoover placed Utah’s rock spires and delicate formations under government protection. That didn’t change things too much: Even after the birth of the interstate highway system, only 127,000 people ventured into Arches National Monument in 1966. But in 1971, Congress voted to change Monument to Park, and within five years, annual traffic jumped to nearly 300,000. Today, it’s at 860,000. The lesson? For any plot of earth worth loving, that four-letter word is a khaki-colored stake through the heart.

Declaring an area a national park is asking for it to be exploited. And I’m not even talking about the budgetary shortchanging that was reported by the National Parks Conservation Association in late June. (The nonprofit’s survey gave the parks C’s and D’s in everything from air quality to upkeep and raised serious concerns about adjacent construction and highways within the protective boundaries.)

No, my beef is simple: Color it green on the road atlas and the expectation is that it will be, well, a park—a safe, manicured humanscape maintained for the enjoyment of people. Take the same piece of land, color it brown, and call it a national monument and visitorship is cut in half. Call it a wildlife refuge and another 50 percent won’t bother to show up. The parks could use more money, but mostly they need to stop being, well, parks. That’s right: Adios, Acadia. Sayonara, Saguaro.

The logic of national parks baffles me. We identify our most breathtaking, often endangered ecosystems for protection. We run environmental studies on them, catalog the wildlife, and elevate them incrementally through the gamut of designations before crowning them parks. Then the construction begins: Roads are cut and graded; 18,000-square-foot visitor centers are framed; stairs and railings emerge from cliffs and canyons. Soon, hotels and pancake houses bloom near the gates—or, worse, an entire neon tourist trap takes root, like Gatlinburg did at the edge of Great Smoky Mountains. It’s only a matter of time before second-home owners are tazing wildlife on their morning jogs. Take note, all ye backers of schemes for Maine Woods and Mount Hood national parks: Do you really want go-cart tracks and a petting zoo on your doorstep?

But if designations are what have doomed our splendid vistas, they’re also the solution. Let’s ban new national parks and downgrade the ones we can still save from the creeping plague of mall-like visitor centers, boardwalks, and “scenic loops.” Then rename the areas with more traditionally bureaucratic titles. Who would expect a paved campground at the Glacier National Frozen Precipitation Conservatory? Or the Rainier Extinct Volcano Near Seattle? I might be tempted to keep driving if I encountered signs for the Great Sand Dunes Deposited Silica Preserve. Try fitting that on a commemorative spoon.

The truth is, we love our parks, and we’ll probably never get rid of the fancy hats and gift-shop shot glasses. They’re as American as Twinkies. But we have to start managing them like what they are: highly sensitive ecosystems, not items on a checklist of RV destinations.

So what can you do? If you must visit the parks, then use them: Actually walk them instead of driving the loop. Give the superintendents reason to allocate more money for restoration instead of well-lit toilets and overflow parking. Better yet, seek out your own personal park that doesn’t carry the label. There’s plenty of public land as beautiful as, and less crowded than, official parks. Try an obscure refuge, national forest, or state park.

One of my favorite places is the 100,000-acre Valle Vidal, in northeastern New Mexico. It’s designated a mixed-use area—and sure enough, the Japanese don’t know about it. True, there’s an occasional worn-out refrigerator dumped there and you’ll sometimes find empty shotgun shells and beer cans. It could use more protection from loggers and drillers. But there are no visitor centers or hot-dog stands. And it gives me what the Grand Canyon and Yellowstone promise but can no longer deliver: solitude and nature in its raw form.