FOR MOST AMERICANS, coming of age means getting a job or finishing a triathlon (or, let’s be honest, a keg). For a few, however, as the authors of two new books make clear, the boys-to-men moment that shapes a person can nearly destroy him in the process.

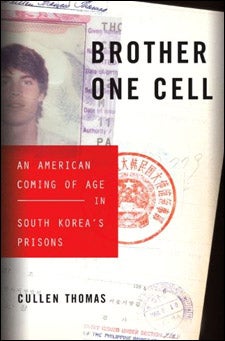

Brother One Cell

In 1994, while visiting the Philippines, 23-year-old Cullen Thomas mailed two bricks of hashish to the post office in Seoul, South Korea, where he was working as an English teacher. When he returned to cash in, he was busted and sentenced to three and a half years. In Brother One Cell: An American Coming of Age in South Korea’s Prisons (Viking, $25), the first-time author chronicles his kimchee-laced Midnight Express odyssey in reflective, often highlighter-worthy prose. Thomas sleeps on cold concrete in Taejon Prison’s Block 6, a “criminal United Nations” for Korea’s 50 or so weigookeen (foreign) felons. But physical discomfort is the least of his worries as the months drag on, he battles isolation, guilt, and rage. Thomas, now a Brooklyn-based freelance writer, lyrically describes his Zenlike efforts to stay sane through shoe-factory work and prison basketball. “I don’t know if life will ever again give me something so pure and hard and unrelenting, so savagely true to itself,” he writes. “As trying as it was, I would never give the experience back.”

It’s hard to say whether Marine captain John Bissell feels the same about his mid-sixties stint in South Vietnam. But his son Tom Bissell, author of 2003’s Chasing the Sea, hopes to find out when he and his dad revisit the region 40 years later, a trip movingly chronicled in The Father of All Things: A Marine, His Son, and the Legacy of Vietnam (Pantheon, $25). As they crawl through Vietcong tunnels, shoot AK-47’s, and visit former battlegrounds like Saigon and Tuy Phuoc where a booby trap almost took John’s life Bissell prods his taciturn father to reflect on his own past. But like an entire generation’s feelings about the war itself, the old soldier’s response to their journey is ambivalent, oscillating between regret, pride, and indifference. Every vet should return to witness a healthier, recovered Vietnam, Tom argues: “That’s how you kill a ghost. You replace it with one that’s real.” His father’s reply: “That’s very easy to say when you’re not the haunted one.”

Buy and ��