WITH HIS BEARD and tweedy jacket, Richard Lindzen looks like a cheerful physics professor from the fifties, inspiring nostalgia for the age of space exploration and other grand, forward-looking American endeavors. On a cold March evening in New London, Connecticut, the 67-year-old atmospheric scientist from MIT is trying to serve up a little optimism about the gloomiest topic of our time: global warming.

Richard Lindzen

Richard Lindzen

Richard LindzenInconvenient Expert

Optimism? Yeah, as in: Don’t worry about a thing. Just now, Lindzen is scoffing at the widely accepted view that CO2 buildup is to blame for the heat waves, prolonged droughts, and intense hurricanes that the U.S. and other countries have experienced in recent years. At a time when much of the nation’s political, intellectual, and business leadership accepts the idea that people are the cause of global warming, Lindzen loudly disagrees.

“All scientific issuesÔÇöand this is no differentÔÇöare difficult to understand,” he tells a group of cadets and locals assembled in an auditorium at the U.S. Coast Guard Academy. “Extreme weather events are always present. There’s no evidence it’s getting better, or worse, or changing.”

Lindzen’s relaxed delivery gives the audience a comfortable sense that they, like him, are smart enough to question the pronouncements of nervous scientists and high-octane advocates like Al Gore. Skepticism is a good idea, he says, since so many people who sound off about global warming don’t bother to read the documents that supposedly forecast climate apocalypse. “The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report, if you read itÔÇöand no one does …” he says, and that phrase alone prompts laughter.

This ability to put people at ease helps explain why, after nearly two decades of effort, Lindzen has achieved exalted status among the current crop of global-warming doubters. He has personally briefed President Bush’s top science adviser on climate change and is very popular with senior GOP lawmakers on Capitol Hill. He publishes opinion pieces in The Wall Street Journal and speaks publicly several times a month, both in the U.S. and abroad. With so many Americans searching for answers on climate change, an endowed MIT professor with pithy quotes offers a level of assurance that few can rival.

In doing so, however, Lindzen is challenging the scientific establishment, which tends to sing in scary harmony about this issue. The UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is an international scientific body, 2,500 researchers strong, that weighs in on the planet’s climate health every five years or so. Earlier this year, the IPCC rolled out a series of three massive documents asserting that global warming is an established fact and outlining where it all will lead.

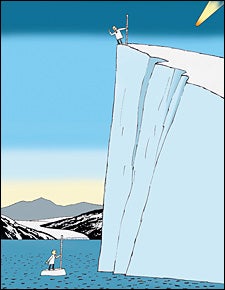

The reports maintain that there’s more than a 90 percent chance that human activityÔÇöprimarily the burning of fossil fuels, resulting in increased levels of atmospheric CO2ÔÇöis responsible for the earth’s recent warming, which amounts to a 1.2-degree-Fahrenheit rise in global mean temperature over the past 100 years. Noting that the current atmospheric concentration of CO2 is higher than it’s been in the past 650,000 years, the IPCC predicts that human-induced climate change could spell extinction for 20 to 30 percent of the world’s species by the end of this century, cause increasingly destructive weather patterns, and flood coastal cities.

Lindzen doesn’t dispute that the planet has warmed up in the past three decades, but he argues that human-generated CO2 accounts for no more than 30 percent of this temperature rise. Much of the warming, he says, stems from fluctuations in temperature that have occurred for millions of yearsÔÇöexplained by complicated natural changes in equilibrium between the oceans and the atmosphereÔÇöand the latest period of warming will not result in catastrophe.

Whether such arguments are true, false, or nuts, they seem to make an impression on the Coast Guard crowd. Edward Hug, a Massachusetts retiree who came to hear Lindzen speak, is exactly the kind of person the professor wants to sway. Hug, who used to work in underwater acoustics for the Naval Undersea Warfare Center, says he’s been diligently trying to educate himself about global warming.

“I’ve seen Al Gore’s film twice, but I’ve also read Michael Crichton’s State of Fear, which makes a compelling case on the other side,” says Hug, referring to the controversial 2004 novel in which CrichtonÔÇöusing scientific arguments that were hotly challenged by criticsÔÇöridiculed the global-warming consensus as the work of conspiratorial alarmists.

Hug sees the IPCC as “the closest thing to a gold standard when it comes to science,” but he still wants to know whether Americans have to change their lifestyles radically in order to save the planet. “The question is,” he said earlier as he settled in to hear Lindzen, “is it worth making the sacrifice?”

By evening’s end, he decides to join the skeptical camp. “I find him very convincing,” Hug says of Lindzen, recalling how he invoked scientific data and theories to buttress his points. “He’s just as good as Michael Crichton.”

SOMETIMES THE AMERICAN people seem convinced that global warming means everything has to change; sometimes they don’t. An April poll conducted by The Washington Post, ABC News, and Stanford University showed that 70 percent of U.S. voters think the government should take action to ward off climate change. But even though 84 percent of the poll’s respondents said they believed the world’s temperature has been rising over the past century, only four in ten said they are “extremely” or “very” sure it is happening.

Meanwhile, in late May, President Bush vowed to alter his hands-off attitude about climate change, announcing that the U.S. would lead talks among the world’s largest greenhouse-gas producers in an effort to reach a new accord before he leaves office. But whether he will follow through on that remains to be seen. As for the rest of us, how about all those Live Earth concerts? Did they inspire you to change anything other than your TV channel?

In recent months, Lindzen’s circle of allies has appeared to be expanding rather than shrinking. In late May, Michael Griffin, administrator of NASA, which conducts considerable amounts of climate research, told National Public Radio that he was not sure climate change was “a problem we must wrestle with” and that it was “rather arrogant” to suggest that the climate we have now represents the best possible set of conditions. Alexander Cockburn, a maverick journalist who leans left on most topics, lambasted the global-warming consensus last spring on the political Web site CounterPunch.org, arguing that there’s no evidence yet that humans are causing the rise in global temperature. Other skeptics include Czech Republic president V├íclav Klaus; Roy Spencer, a principal research scientist at the University of Alabama in Huntsville; and Patrick J. Michaels, a senior fellow in environmental studies at the libertarian Cato Institute.

Cockburn based much of his article on the work of Martin Hertzberg, a consultant from Copper Mountain, Colorado, who worked as a U.S. Navy meteorologist for three years. According to Hertzberg, the increase in CO2 is happening because the world’s oceans are warming upÔÇöa natural process that’s been occurring since the end of the most recent ice age, 12,000 years agoÔÇöand in doing so they’re releasing their dissolved carbon into the atmosphere.

Most climate experts react harshly to such backtalk. Sir John Houghton, a British atmospheric physicist who chaired the IPCC’s Scientific Assessment Working Group from 1988 to 2002, says skeptics have conducted a “misinformation campaign” in the U.S. that must be brought to an end. Earlier this year, Boston Globe columnist Ellen Goodman hurled one of the worst insults imaginable at the skeptics’ camp. “I would like to say we’re at a point where global warming is impossible to deny,” she wrote in February. “Let’s just say that global warming deniers are now on a par with Holocaust deniers, though one denies the past and the other denies the present and future.”

This sort of declaration, understandably, makes global-warming skeptics feel persecuted. Lindzen lost almost all of his father’s family and most of his mother’s to the Holocaust, and he says he considers Goodman’s comments “mostly stupid, and a bit disgusting as well.”

Other skeptics argue that the normal processes of scientific debateÔÇögathering and analyzing data in order to make a case for a particular set of ideasÔÇöare getting pushed aside with this issue, leading to dangerous groupthink about how best to prepare for the future.

Danish writer Bj├Şrn Lomborg underscores this point in his new book, Cool It: The Skeptical Environmentalist’s Guide to Global Warming. Though he agrees that global warming is happening and that human-generated CO2 is a contributing factor, Lomborg questions whether “hysteria and headlong spending on extravagant CO2-cutting programs at an unprecedented price is the only possible response.”

The skeptics’ campaign has drawn fire from some of the nation’s top scientists, who say their problem with Lindzen and other doubters is simple: They’re wrong. Lindzen’s critics say his dissent consists of taking cynical potshots at the consensus model of global warming and that he chooses to pick his fights before general audiences who don’t understand the science.

“He is treating this issue like a smart defense attorney,” says John Holdren, a prominent environmental scientist and past president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. “He’s trying to get his guilty client off. Dick’s guilty client is the proposition that the human impacts on global climate are dangerous.”

Senator Barbara Boxer, an influential California Democrat who chairs the Environment and Public Works Committee, is just as critical of Lindzen. “The world’s leading scientists are saying we know enough to act now,” she says. “If, in the past, we had listened to a small number of skeptics, we wouldn’t have addressed dirty air or endangered species or toxic-waste sites, and our quality of life would have suffered greatly.

“It would be irresponsible,” she adds, “to let a few skeptics stand in the way of doing what we need to do to stabilize the world’s climate.”

LINDZEN DOESN’T MIND getting bashedÔÇöthe criticism bolsters his sense that he’s fighting for the truth. “I feel that my field is being raped, and someone should do something about it,” he says.

John M. Wallace, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Washington who has known Lindzen since their grad-school days in Cambridge, Massachusetts, says Lindzen’s challenge to climate-change orthodoxy is driven, in large part, by his inner resistance to backing down. “That is Dick’s natural personalityÔÇöto be somewhat of a contrarian,” Wallace says. “He feels he can work the argument and win.”

Lindzen is also accustomed to charting his own course and trusting what his brain seems to tell him. Raised in the Bronx by immigrant parents, Lindzen graduated from the Bronx High School of Science in 1956, started college at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, then transferred to Harvard after two years, graduating in 1960 with a bachelor’s degree in physics. He didn’t intend to specialize in climatology when he stayed at Harvard to pursue a graduate degree, but he won a fellowship in atmospheric and ocean science that allowed him to continue studying his first love: applied mathematics and physics.

Early on, Lindzen’s exceptional math skills helped shape his career. For a series of papers he published in the late sixties and early seventies, he chose to tackle a complex phenomenon involving thermal currents in the atmosphere that scientists had been trying to explain for decades. “Lindzen figured out how to mathematically solve the problem,” says Wallace. In 1977, this work helped get Lindzen elected to both the National Academy of Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He was awarded an endowed professorship at MIT in 1983.

In 1990, two years after NASA scientist James E. Hansen issued his now famous warning about climate change during a congressional hearing, Lindzen started taking a publicly contrarian stance when he challenged then-senator Gore by suggesting in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society that the case for human-induced global warming was overstated and that natural climate variability could explain things just as easily. In 1992, he served up similar arguments at a Vienna conference on the science and economics of global warming that was hosted by OPEC and marked by unruly protests from environmentalists.

Lindzen tends to relate these stories with mild sarcasm, implying that the listener is surely sophisticated enough to perceive his opponents’ foibles. “They were actually trying to climb in the building,” he recalls in a deadpan tone. “It was kind of strange, but these were Europeans.”

Lindzen’s critiques usually focus on how current climate models can’t explain everything and how their proponents conveniently ignore facts that don’t fit their assumptions. He points out, for example, that there’s been a period of global cooling since the 18th-century onset of the Industrial RevolutionÔÇöfrom the 1940s to the 1960sÔÇöand that average temperatures rose in Europe between 1050 and 1300, even though there was no heavy industry going on back then.

At the moment, Lindzen is pursuing a theory that says increased amounts of water vaporÔÇöfrom warming surface temperaturesÔÇöwill reduce heat-trapping high-cirrus clouds, which will help balance the planet’s temperature. This concept is significant, because most climate scientists believe water vapor will exacerbate the warming effect of greenhouse gases. Lindzen and some scientists at NASA have offered a hypothesis that warming in the tropics will reduce high-cirrus cloudiness there, which will increase outgoing heat more than it increases the heating effect of incoming sunlight. While this theory has sparked serious academic debate, most experts took a pass after a group of researchers criticized it in a 2002 paper for the Journal of Climate.

Stanford University climatologist Stephen H. Schneider, who helped write an important chapter of the IPCC report on global warming’s potential impact, has debated Lindzen frequently in academic forums and compares his critique to the traditional scientific method of Karl Popper, which involves testing a theory by looking for flaws. But Lindzen has gone too far, Schneider says, because, given the complexity of the subject, it makes no sense to focus on a few unexplained aspects of human-induced warming when the overwhelming indicatorsÔÇöalong with current temperature and weather patternsÔÇösuggest that the theory is right.

Schneider recognizes that global warming may not wreak catastrophic changeÔÇöin fact, he puts the chances at roughly 50-50. But given those odds, he argues, we’re better off acting as if catastrophic warming is a 100 percent lock. “The chance of an asteroid hitting the planet is one in a hundred million, so we don’t worry about that,” he says. “Significant climate change is a coin flip, so we do.”

Many critics don’t give Lindzen as much credit as Schneider does, suggesting that he’s a tool for Big Oil. In 1995, Ross Gelbspan, writing in Harper’s, pointed out that in 1991 Lindzen testified before Congress as an expert witness and that the Western Fuels Association, an industry group, paid his trip expenses to Washington.

While Lindzen did accept the expenses, this doesn’t mean he’s on anybody’s payroll. He charges for his speeches, but so do prominent scientists who disagree with him about climate change. (Lindzen gets between $5,000 and $10,000 for speaking to a corporate group and between $1,000 and $2,000 for noncorporate gigs like the Coast Guard Academy appearance.) As his friend Wallace would attest, his main motive is conviction. He’s sure he’s right, and he revels in his contrary ways.

This is, after all, a chain smoker who thinks the evidence linking secondhand smoke to lung cancer is iffy. With a wife and two grown sons, he lives the classic, comfortable life of a New England professor, residing in a wooden clapboard house in Newton, Massachusetts, filled with shelves crammed with books and LPs of classical music, opera, jazz, folk, and musical comedy. He remained a Democrat until 1991, even as he questioned whether global warming mattered, switching to the GOP only after many prominent Democrats had excoriated him.

Lindzen doesn’t have any use for most environmentalists, and even when he does something “green,” he sniffs at the idea that he’s following their lead. He uses compact fluorescent lightbulbs in many of his lamps at home but emphasizes, “It’s not to save the world. It’s to save on our electric bills.”

LINDZEN’S ACTIVISM HAS earned him plaudits from conservative politicians like Senator James Inhofe, the Oklahoma Republican who has labeled global warming “the greatest hoax ever perpetrated on the American people.” Inhofe has hailed Lindzen for presenting “a clear and coherent scientific counter to unfounded climate alarmism.”

Lindzen’s professional colleagues have been less kind, and there’s no doubt that climate-change believers are aggressive proselytizers. But Lindzen insists that scientists cannot say precisely what the future holds, because they’re just beginning to analyze some of the more complicated responses to climate change, such as how quickly ice sheets melt and to what extent this will raise sea levels. To him, these uncertainties are the heart of the matter, and they’re why he feels justified about voicing dissent.

While the two sides differ on a number of questions, the debate really comes down to one thing: whether the warming we’ve begun to see poses a pressing problem or is something the world can adapt to over the long haul. According to Kalee Kreider, a spokeswoman for Al Gore, it is this question, more than any other, that embodies the difference between Lindzen and the former vice president.

“Where [Lindzen] disagrees is the issue of urgency,” she says. “We just feel he’s out of step with the mainstream scientific community.”

To some extent, Lindzen has enjoyed success in getting his message out. The Washington Post/ABC/Stanford poll found that, while 70 percent of respondents want the U.S. government to do more to address climate change, 56 percent believe the academic community remains divided on the issue.

Meanwhile, book sales and TV ratings seem to indicate that global-warming skepticism is finding an audience. The Great Global Warming Swindle, a recent documentary featuring Lindzen and other skeptics, attracted 2.5 million viewers in Britain, prompting the Australian Broadcasting Corporation to buy the international rights so they could air it this summer.

The market is currently awash in books that, like Lomborg’s Cool It, attack the majority viewÔÇöincluding Crichton’s novel, Christopher C. Horner’s The Politically Incorrect Guide to Global Warming and Environmentalism, and Unstoppable Global Warming: Every 1,500 Years, by Dennis T. Avery and S. Fred Singer.

Chris Rapley, who directs the British Antarctic Survey, watches the success of what he calls “the professional confusers” with horror: After the documentary aired in Britain, the mother of one of his most talented ice-core analysts called her son to make sure he was certain climate change was really a problem. The film skewed key facts, Rapley said, but its real power lay in the fact that it appealed to people who don’t want to think they’re helping usher in an era of environmental disaster. “It’s a message people wanted to hear,” he says.

But while Lindzen and his allies are competitive in the marketplace of ideas, they’re losing in America’s cloakrooms and boardrooms. Democrats, who control Congress, aim to pass legislation in the coming months that will impose the same regulatory scheme that Lindzen opposes, a cap on CO2 emissions. And a host of traditional foes of such government-driven fixes, including the Big Three automakers and ConocoPhillips, now endorse it.

The 2008 election may determine whether Lindzen will continue to have a meaningful role in the public debate over climate change. If any of the Democratic candidates wins, Lindzen will be sidelined even further, since all of them are prepared to regulate emissions. The GOP field remains mostly in lockstep on the issue: John McCain backs mandatory cuts in greenhouse gases, but the remaining Republican candidates are much less enthusiastic about the prospect of such massive regulation.

Even more telling, though, is the attitude of businessmen, who increasingly see the wisdom of investing in CO2-mitigation strategies. Last winter in Miami, during a private meeting convened by an outfit called the Tudor Investment Corporation, more than a hundred portfolio managers gathered at the Mandarin Oriental Hotel to hear opposing speeches from Lindzen and Schneider on whether to factor global warming into investment decisions.

The two men separately made their case. Lindzen told the group that future warming wouldn’t be dire. But when Schneider spoke, he appealed to the audience on blunt economic grounds. Catastrophic climate change, he argued, amounted to the kind of “low-probability, high-consequence risk” that investors usually seek to avoid. Tudor analysts could make their own decisions about whether he or Lindzen would end up being right, he added, and that decision would have huge financial consequences.

“I’m going to be right,” Schneider added, drawing a laugh. “So then it’s going to be a good thing you hedged.”

After Lindzen and Schneider spoke during an afternoon session, Tudor’s CEO, Paul Jones II, asked Schneider to come to his suite the next morning to chat about the company’s future. “We had a long conversation on how they should invest,” Schneider recalls. “It was not a matter of when, but how.”

Lindzen left Miami without having done more than engage in cocktail chatter with Jones. He headed back to Newton and readied himself for the next PowerPoint presentation he had to deliver in a darkened room. But he wasn’t bothered by the snub, since he believes he’ll be vindicated eventually.

“My best guess is, 20 years from now it will be accepted that global warming is not an issue, and everybody will claim they knew it all along,” he says, adding that he’s not holding out hope of being recognized for his work by future generations. “Chances are, 20 years from now I’ll be dead,” he jokes, “and someone else will want to take credit.”