IT’S 9:30 a.m. on a Friday in September, almost ten hours after the midnight start of his attempt to parachute off Twin Falls, Idaho’s Perrine Bridge 50 times in 24 hours, and BASE jumper Miles Daisher is sitting unusually still. He’s slouched in a folding camp chair 486 feet below the bridge in the Snake River Canyon, near his landing zone. A large, open-sided tent emblazoned with the logo of his primary sponsor, Red Bull, shades Miles from the midmorning sun, while a small crew of his close friends pack parachutes and glance worriedly at the man they’re here to support.

JUMP HAPPY: Miles Daisher photographed on November 1, 2005

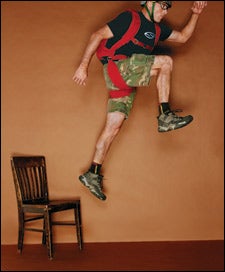

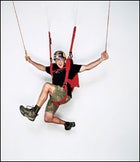

JUMP HAPPY: Miles Daisher photographed on November 1, 2005 FLYING MAN: “Jumping is relaxing for me“, says Daisher.

FLYING MAN: “Jumping is relaxing for me“, says Daisher.

MIGHT AS WELL JUMP: BASE specialist Miles Daisher -Photo by Art Streiber

MIGHT AS WELL JUMP: BASE specialist Miles Daisher -Photo by Art Streiber“The pace is definitely slowing down, dude,” says Miles, 36, as he munches joylessly on a banana. “Gotta rally.”

While the rest of the world has been sleeping, Miles has thrown himself off the bridge 31 times—six more than the previous record of 25, set in February 2002 by American Ed Trick during a day of jumping off the 900-foot KL Tower, in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. After each jump, Miles has clawed his way back up to the canyon’s rim, a 15-minute scramble through scree, boulders, and poison oak, amassing 15,000 vertical feet of hiking in ten hours—equivalent to climbing to the top of the Empire State Building 12 times.

If the whole record attempt seems a bit contrived, that’s because it is. Most of the BASE jumpers in attendance had no idea beforehand who the previous record holder was or even that such a record existed. BASE jumping—the acronym stands for “buildings, antennae, spans, and earth,” the four main categories of fixed launchpads for low-altitude parachute jumps—has no governing body, no fixed set of standards, and a corps of practitioners with little interest in quantifying or publicizing the sport. All of which makes Miles and his record attempt something of an anomaly.

But for Miles, the record is just one part of a multifaceted event—a reunion of his jump buddies, most of whom are from the Tahoe area, where he used to live; a beacon of positive attention for his peripheral sport and himself; and a fundraiser for the Magic Valley Regional Medical Center Foundation’s program to help local children with disabilities. (Miles’s 29-year-old wife, Nikki, is an occupational therapist who works with special-needs children.) At this moment, Miles is still 19 jumps and seven hours shy of the 5 p.m. charity raffle and gala tailgate (complete with “music, munchies, and libations”) that he’s planned to coincide with his 50th jump. Still further off is his “real” target: 60 jumps and hikes—roughly equivalent, he likes to say, to a climb from sea level to the top of 29,035-foot Mount Everest in a single day. Now he just has to get going again.

Miles threw down an astonishing ten jumps and hikes in the first two hours and sent his heart-rate monitor into paroxysms of beeping, topping 170 beats per minute. “It doesn’t feel like I’m doing anything exerting; it’s just fun,” Miles insisted while taking a brief break at 2 a.m. to let his heart rate drop. In an instant he was off again, singing, “Well, I’m hot-blooded. Check it and see. I got a fever of a hundred and three . . .”

But that was then. Right now, Miles has managed only two jumps in the last hour. Hiking back up after jump 31, he stumbles slightly. His friends begin to wonder aloud if he has the juice left to make even 40 jumps, let alone 50 or 60. There’s a cheer from the small crowd in the observation area on the canyon rim, and then Miles is hurtling through the air again. Thirty-two down. When he walks back into the tent, he collapses onto the carpet: “I’m just gonna lay down for a bit.”

Just then, the walkie-talkies strewn about crackle to life with the voice of Shane McConkey, 36, extreme skier, fellow BASE jumper, and Miles’s “best bro.” He’s just flown in from Truckee, California, in a Cessna piloted by another of their buddies.

“Hey, is there a world-record holder down there?” Shane asks.

“I did ten in the first two hours, blew my wad a little fast,” Miles says. “I’m regrouping.”

“Well, get your ass up here so we can jump.”

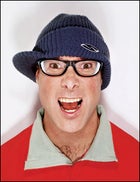

TWIN FALLS, POPULATION 38,000, at first seems an unlikely home for a thrill-seeking former ski bum. There is little in the compact, flat grid of downtown or the sprawl to prepare you for the animated, excitable five-foot-nine-inch man with the loud voice, bouncing gait, receding hair, and arms too long for his body. Miles doesn’t exactly blend in.

“They don’t speak California Dude here,” says Mike Vail, 35, another of Miles’s friends from his Tahoe days. “Which is a problem, ’cause that’s the only language Miles knows.”

When Miles moved to Twin Falls from Truckee a year and a half ago with Nikki and their daughter, Dorothy, now 18 months old, it was partly a concession to the family-guy role he’s still growing into. Nikki’s family is from Twin Falls, so the move gave them a support network and an opportunity to invest in some real estate. They live in a three-bedroom house in a suburbanized tract west of town, and also own three rental properties and a fixer-upper that Miles has spent the last year renovating.

But there is another perk for Miles in Twin Falls: the Perrine Bridge. A massive steel arch supporting a 1,500-foot-long span, it carries the four lanes of U.S. 93 across the Snake River Canyon. Daredevils are nothing new here—Evel Knievel tried and failed to jump the canyon on a jet-propelled motorcycle in 1974—but lately the bridge has attracted a new breed.

Owing to Idaho libertarianism and overlapping jurisdictions, jumping here is what it rarely is on such man-made objects elsewhere: legal. While it’s legal to jump off many cliffs and natural objects (excluding those in national parks), the owners or overseers of bridges, towers, and buildings are reluctant, for obvious liability reasons, to grant jumpers permission. The constant threat of prosecution means that most BASE jumping happens covertly, often under the cover of night. As word has spread that there’s a beautiful bridge you can leap from in the light of day, BASE enthusiasts from all over the world have arrived in force. More than 100 of them showed up for a jumpfest this past Labor Day weekend. And the town has opened its arms to jumpers, even featuring them on the hats and T-shirts sold in the visitor center near the bridge.

Miles began his jumping odyssey in 1992 while a student at California’s Chico State University. His friend Jim Fritsch, founder of a local bungee outfitter, hired Miles for his ground crew. Miles began doing jumps, and from the start his experience with gymnastics and diving showed in his acrobatic flair. After graduating in 1993, Miles made the short hop up to Squaw Valley, California, in the Lake Tahoe area, and stayed 11 years. He ski-bummed, worked bungee, and took odd jobs to support a jump habit that grew to include skydiving after he received certification in 1995. He soon fell in with a group of jump-happy friends at the nearby Parachute Center, in Lodi, California, a crew that included Shane and Frank “the Gambler” Gambalie, Miles’s roommate at the time and the man responsible for getting the rest of them into BASE jumping.

A leader of the sport’s late-nineties new wave, Gambalie eventually agreed to mentor Miles and Shane, teaching them skills like BASE-specific parachute packing, the ability to judge wind direction, speed, and object height, and how to approach different types of landing zones. Sadly, in 1999, after a successful but illegal jump off El Capitan, Gambalie drowned in the Merced River while being chased by Yosemite park rangers.

Such tragedies dot the history of BASE jumping. Unlike skydivers, whose reserve parachutes and high-

altitude jumps allow them to fix certain problems, if something goes wrong during a BASE jump, it tends to go irreparably wrong. In the past 25 years there have been nearly 100 BASE fatalities—at least six in 2005 alone—the vast majority from impact with the BASE object itself. (Miles broke his shoulder skydiving but has avoided any BASE-related mishaps.)

In spite of its obvious dangers, BASE is in the midst of a growth spurt, emerging, like other “extreme” sports before it, from the outlaw shadows into the pale light of mild exposure. “We’ve had a huge growth wave in the last five years,” says Tom Aiello, 33, head of the Snake River BASE Academy, in Twin Falls. Growth, however, is relative. Statistics are a tricky thing in a sport that is still mostly underground; current estimates put the number of BASE jumpers worldwide at about 5,000, though the number who jump regularly is probably a quarter of that.

But none of this deters Miles. “I’m all about proving that BASE is a total spectator sport,” he says, explaining the larger purpose of his record attempt. He dreams of BASE being in the X Games and wants to convince a wider audience to see jumpers as athletes rather than as lunatics.

His publicity-hungry attitude has attracted criticism from some in the BASE community, who see Miles as a glory hound whose antics could endanger the sport’s legality in places like Twin Falls. But he’s determined to take BASE off the fringes, partly out of necessity. Although Miles has several paying sponsorships (including Red Bull, Patagonia, Smith, and Teva), has started a jump school in Twin Falls, and is hopeful that a TV pilot about his record attempt will be picked up for a cable series (“a reality show built around jumping off stuff”), BASE jumping isn’t paying all the bills yet.

“If this idea works,” he says, flashing a grin, “this is a catalyst for hugeness.”

TWO DAYS BEFORE THE START of the attempt, Miles was standing on his front lawn, bent over an ailing mower that, like every other mechanically driven item associated with him—cars, boats, power tools—seemed to have had its last legs amputated years ago. The Daisher homestead suggests suburban domesticity slightly tweaked, the white vinyl siding concealing a garage full of parachutes, kayaks, and bowling balls.

“Can’t have the lawn half mowed when everyone starts showing up for this thing,” Miles said. “Plus mowing the lawn’s kind of a Zen thing for me. It’s like therapy, makes you forget about all the other stuff.”

The pre-event frenzy was a constant reminder that, though adventurous lives like Miles’s are easy to romanticize, prosaic details are not easily escaped. There were diapers to be changed, bills to be paid, and dogs to be fed. The house phone and two cell phones rang constantly. Nikki handled most of the calls. She’s quieter and more pragmatic than her husband and has learned to take the danger element of what he does in stride. He is a safety fanatic, she pointed out, “and he’s good about keeping his head about him. I trust him to make the right decisions.”

But Miles was clearly feeling the weight of the upcoming record bid. “I’m almost starting to get nervous,” he told me as we cruised to Costco in Blue Thunder, his 1990 Subaru wagon with 300,000-plus miles on it. “Not about the jumping but all the logistics of this record-attempt thing.” His publicity efforts, at least, were starting to pay dividends. Regular plugs on local radio (“This Friday, for one day only . . .”) and extensive coverage in the Twin Falls Times-News meant that he’d arrived as a local celebrity.

“I saw your face in the paper,” said the old woman in the optical department at Costco when we dropped by to pick up a new pair of glasses Miles had ordered. “You jump off bridges.”

“Yeah, that’s me,” he responded, laughing shyly. The glasses, it turned out, were not ready yet, which was a problem, because without them he would have a hard time seeing well enough to land safely at night.

“I’m so sorry,” she said. “I’ll call and tell them you need them as soon as possible, and that you jump off bridges. They won’t believe me, but I’ll tell them.”

At our next stop, the guys at the tool-rental shop called Miles crazy, then asked him to autograph their newspaper, gave him half off on the generator price, and threw in all the halogen lights he needed at no charge. At Quiznos, the teenage boys making our sandwiches asked some excited questions about jumping and gave us a 75 percent discount, most of which Miles then stuffed into their tip jar. Miles never did get the lawn mower working that day, but things were looking up. ESPN2 had confirmed they’d be doing live interviews with Miles every 15 minutes for an hour and a half on their morning show, Cold Pizza.

“This is going to be huge, man,” said Miles. “It’s all exploding.” As Nikki came out of the house holding Dorothy, Miles turned to her. “My head’s blowing up, baby.” Then he lowered his face to the infant’s level. “What do you think of your daddy, Dorothy?”

“You’re not there yet, honey, you’re not there yet,” said Nikki, cutting off Miles’s self-congratulatory baby talk and handing him their daughter. “Keep it real.”

EVENTUALLY THERE WAS NOTHING LEFT for Miles to do but jump. Ten minutes before his start time of 12 a.m. Friday, September 16, after a flurry of last-minute delegation, the look on his face could only be called one of relief. “Jumping is relaxing for me,” he says. “It’s everything else that’s stressful.”

A reporter from the radio station went live via his cell phone at 11:59 p.m.: “He’s up on the rail now, the crowd egging him on, and he’s awaiting his final countdown.” The crowd of friends, fans, and reporters counted down from ten. Then Miles smiled, shouted his standard exit line (“Ready, set, see ya!”), and plummeted into the canyon, lit by the full moon and the floodlights and doing an impossible number of flips and twists. By 7:40 a.m., Miles had done 27 jumps and was grinning his way through an ESPN interview. He’d become a sort of rock star, the crowd swollen with adults on their way to work and kids on their way to school, all cheering, snapping photos, touching him.

“Oh, man. It’s getting huge up there!” Miles says now, at 11 a.m., after landing number 33, which featured Shane and Miles throwing near-synchronized triple gainers (forward-facing backflips of three rotations) off the safety rail.

“Dude, you’re the world’s greatest BASE jumper,” Shane says, after high-fiving Miles in the landing zone.

“I thought you were, dude,” responds a rejuvenated Miles.

“No, I’m the greatest BASE jumper in the world,” says Shane. They laugh at their well-worn Abbott and Costello–type routine. By noon, Miles has tallied 37 jumps; by 2 p.m., 43.

“I’m getting my fourth wind now,” Miles says, returning to the tent after jump 43, his voice slightly hoarse from the woo-hooing. “It’s all that energy from those people up there, dude, and now when I’m running through, all these kids are running over to high-five me. It’s unreal.”

At 4:30 p.m., there begins a gradual exodus of Miles’s friends from the tent to the top for the group jump that will mark number 50. The crowd now numbers more than 500. “There he is!” shouts one of them when Miles hikes into view, igniting a chorus of cheers and whistling. Miles bounces down the walkway to the middle of the bridge, Nikki and Dorothy beside him. He stops to give a quick interview and kiss Nikki, and then he and four of his friends tumble off the bridge simultaneously, followed by a cascade of cheers and two more jumpers a few seconds later. After they all land, Miles gathers everyone for a group cheer.

“Thank you, Twin Falls!”

As his friends slap him on the back, Miles is looking around for a packed parachute. With news of a storm blowing in and more jumping yet to do, there’s no time to savor the moment or its dual milestones: His 50th jump of the day also marks his thousandth lifetime BASE jump.

“My baby girl’s waiting up there for me, and Everest is only ten hikes away,” he says. Then he’s off again.

WHEN MY PHONE RINGS at 11 the next morning, I’m not surprised that it’s Miles. His fun ended prematurely last night when a big windstorm blew in at 8:30 p.m. and stalled him at 57, three short of his Everest. He was having a hard time with the morning-after return to maxed-out credit cards and domestic duties, and spent the day with his bros breaking down the landing zone and other detritus from the record attempt. He also began planning another distraction. Which involves me. And the bridge.

Miles and I discussed the possibility of my jumping before I got to Twin Falls. He insisted it was no big deal. I felt differently, until I completed the first few levels of a skydive-certification course and found that I was strangely excited by the prospect.

The thought of jumping has persisted during my time in Twin Falls as a constant uneasiness in my gut, and as I sit on a cooler in Miles’s garage two days after the record attempt, watching him pack a parachute “with your name on it,” the uneasiness hardens into genuine fear. Miles will be standing behind me, holding my pilot chute to make sure my canopy opens properly. Once I land safely, he’ll jump. Shane will be standing next to me, his helmet cam recording for posterity the precise facial expression of a grown man who might soon need diapers. I am to land in the water, which is less dangerous for first-time jumpers, who may lack the steering skills to manage a ground landing amid the endorphin rush. Mike Vail will be waiting there in a boat to pick me up and film another angle of my triumph—or humiliation.

“It’s not gonna be butterflies in your stomach when you step over that rail for the first time, dude,” Miles told me earlier in the week when describing what a first jump might feel like. “Those’ll be bats.”

And then it’s happening. Step over the rail, ignore the shuddering of the bridge with each passing semi truck because, as Shane reminds me, “You’re going off anyway, one way or another.” Eyes on the horizon, don’t look down. High-five Shane, glance at Miles, eyes on the horizon. Then a voice, my voice, says something that I hear but am not fully conscious of saying: “Three, two, one . . . Jump!”

My memory goes blank for a second, in this case an eternity. Then I’m floating down in an amazing stillness nothing like the jolting rush of air during a skydive. I look up to check my canopy and find my hands already gripping the steering toggles, though I don’t recall grabbing them. I flare my canopy twice, steer out over the middle of the river, absorb the sight of the canyon walls on either side of me and my inflated parachute above me. One final flare, and then I drop the last few feet into the cold water and it’s over. Now I’m the one woo-hooing.

“Dude, you stomped it! I totally knew you would!” Miles says, smiling proudly, as we pick him up at the landing area. My induction as a very junior member of the flying fraternity has been a success. There is much high-fiving. “It kind of makes all that other stuff go out of your head, doesn’t it?” Yes, it does.