THE HEAT SENT the blood screaming through my veins, and the humidity was so thick I could hardly inhale. When I did manage a breath, I could feel a scalding sensation in my throat. As the sweat cascaded off my body, I found myself thinking how nice an IRS audit would be compared with this.

I wasn’t marooned in a sweltering jungle somewhere in the tropics; rather, I was in a country without a single jungle, a country that intersects with the Arctic Circle, in fact, and I was seated in a hexagonal box. More precisely, I was sitting in a roomy Nordic spruce sauna in Heinola, Finland—a dull industrial town some 80 miles northeast of Helsinki—sampling the agony that tomorrow’s competitors would experience during the most skin-scorching event on the planet, the Sauna World Championships.

When I entered the sauna, the thermometer read 230 degrees Fahrenheit. (For comparative purposes, the record high temperature in Death Valley is 134.) But when jets of water hit the stove and the air filled with steam, it felt even hotter. For, as everyone knows, it’s not the heat but the humidity that destroys you. The sweat-loving Finns had, of course, installed a special 18-kilowatt stove—the Terminator—and this kiuas (Finnish for “stove”) was cooking. Where, I wondered, were all those mood-boosting, calm-enhancing negative ions that reputedly dance around in saunas? My mood was wretched, and I was anything but calm.

After two very long minutes, I made a dash for the door, whereupon Kimmo Turunen, a 37-year-old, happy-go-lucky guy from Lahti, Finland, who was training for the SWC, shot me a perplexed look. Later he told me that when I bolted from the sauna, he wasn’t even hot.

Obviously he could take the heat. Finns seem to spend much of their lives in saunas, which, thanks to their special stoves, are much steamier than our arid American counterparts. Virtually every home, office building, and prison has one, and Finns believe that steam can cure almost anything, from bodily aches to sexual dysfunction, from depression to a difficult pregnancy. According to a popular proverb, if a sauna and liquor don’t help, your condition’s fatal.

Some Finns consider the Sauna World Championships just another nutty event, like the Wife-Carrying World Championships or the Anthill Competition or the World Mosquito-Killing Championship their country has hosted over the years. Yet it’s not a matter of national pride to squat naked on an anthill longer than anyone else, or to haul your wife the fastest. Sitting in a sauna is, and that’s why so many Finns take this event so seriously. Besides, the men’s winner gets a week’s vacation in sunny Agadir, Morocco—far from the frozen sludge of a Scandinavian winter.

This year, the Australia-based online betting agency Centrebet.com, the only betting outfit in the world that seems to handicap weird sports like futsal (sort of like soccer) and bandy (sort of like ice hockey), has listed Leo Pusa, a 57-year-old, three-time Sauna World Champion from Helsinki, as the odds-on favorite. But Leo has some stiff competition: First he has to fend off last year’s champion, a 34-year-old welder from Lahti named Timo Kaukonen. According to Leo, he—not Timo—should have won last year, but the judges pulled him from the sauna prematurely because, they said, he was slipping into unconsciousness. Leo maintains that he was simply lost in thought.

Then there’s the upstart Belarusan, a slight, 110-pound 50-year-old named Aleaksandr Katlabai. But he, Kimmo firmly maintains, is no match for the Scandinavians. “A non-Finnish person will never win the Sauna World Championships,” he declared. “Of that you can be sure.”

LAST AUGUST, A FEW days before the event, I visited Leo Pusa at his summer house on the outskirts of Helsinki. Eager to reclaim his world-champion status, Leo immediately invited me to join him in—surprise!—his backyard sauna. In typical Finnish fashion, we stripped naked, sweated it out, then—wrapped in towels—ate and drank our way through a spread of sandwiches, sausages, and a dozen or so beers that Leo’s wife, Marja, had laid out on the picnic table. After the feast we returned to the sauna for more steamy air.

Leo’s electric stove ran on only eight kilowatts, much less powerful than the Terminator. Still, the sauna was 195 degrees and humid enough to make me wish I’d brought along my scuba gear. Leo, who’s built like a bear with a large paunch, was training the way he always does: by logging time in the hothouse. After we sat down on the aspen bench, I asked my host how he perseveres in the face of, if not imminent combustion, at least extreme discomfort.

“For one thing,” Leo said, “you need to sweat a lot, and I sweat so much that it’s dripping off me even when I eat spicy food. But you’ve also got to have sisu.”

Sisu, not to be confused with sissy, is a Finnish word whose rough translation is “guts.” If you have sisu, you can hold on to a rope for a few minutes while dangling over a precipice—and then a few extra hours. Sisu is what sustained the Finns in fighting multiple wars with Russia, while losing virtually every one of them.

“How can I get sisu?” I asked. At the moment I needed something that would help counteract my fear of frying.

“It comes with mother’s milk,” Leo replied, “so you probably have it.”

Maybe because my mother fed me infant formula, I left the sauna right after this exchange. Fifteen or so minutes later, when Leo emerged, he was holding the half-full can of beer that I’d inadvertently left behind. The beer, I noticed, was boiling.

So why doesn’t one’s blood boil, too? Because the human body is a better-designed heat-removal apparatus than a can of beer. The hotter it is, the more we perspire, and our perspiration balances the temperature differential between the surface and the core of our bodies. Of course, this apparatus works for only a relatively short time. A Finn named Reino Tarkiainen told me that he’d once survived a sauna temperature of 300 degrees—for more than two minutes. If he hadn’t gotten out when he did, he would have been toast. Once the temperature of the human body reaches between 105 and 107, irrevocable cell damage begins to occur. It’s only a matter of time before you die.

While Leo and I were training, the other competitors, like Luke Edwards, a 26-year-old dark horse from Australia, were hydrating with beer. Jolly, relatively fit, and about six foot two, Luke was competing in the SWC for the second year in a row. He’d also competed in the World Cell Phone Toss, the Gloucester Cheese Roll, and the Air- Guitar-Playing World Championships. In 2003’s Sauna World Championships, Luke informed me proudly, he was “the Southern Hemisphere record holder,” though he’d lasted only four minutes. He quickly admitted that no one else from the Southern Hemisphere had entered the competition.

“Last year the skin on my ear lobes split open from the heat,” he said.

“Then how come you’re doing it again?” I asked.

“Stupidity outweighs discomfort,” he grinned. “Besides, this gives an unathletic person like me a chance to compete at a sport. I mean, all you’ve got to do is sit and sweat.”

I mentioned that the odds against him winning, according to Centrebet, were 46 to 1.

“Are they that good? They were 81 to 1 against me last year,” Edwards said. “But that’s OK. You have more fun when there’s hardly any chance of winning.”

Before we parted, I asked Luke if he had sisu.

“What’s that, mate?” he said.

APART FROM SITTING in a hot sauna, there’s not a whole lot to do in Heinola, unless sitting in an even hotter sauna qualifies. About ten years ago, a group of nominally sane locals began doing just that, competing with one another to see who could endure the most heat. These fiery matches eventually went national, then international, and finally, in 1999, the Sauna World Championships was born.

On this August afternoon, the first day of the sixth annual SWC, the sky is cloudless, the temperature is 75 degrees, and a breeze is blowing off Heinola’s Päijänne Lake. It’s a perfect setting for watching 78 male and 18 female contestants from 11 countries swelter inside one of two overheated saunas elevated on a capacious stage. The stage is surrounded by a grandstand filled with about 1,500 beer-drinking, sausage-devouring spectators.

The rules for the SWC go like this: The first day there are 13 preliminary heats (aptly named), with six contestants per sauna. The two men from each heat who are the last to leave the sauna under their own steam move on to the qualifying round. The 12 qualifying winners move on to the next day’s semifinals. The six winners of that round move on to the final, where the champion is crowned.

The temperature starts out at 230 degrees; every 30 seconds a half-liter of water hits the stove, which provides the drama of a scorching blast yet doesn’t induce the health risks of an increased temperature. To show they’re still alive, the competitors must give a thumbs-up sign at regular intervals. The only other movement they can make is to wipe the sweat off their faces. They can’t disturb their fellow competitors or even talk to them, which means no cremation jokes.

“I go for sauna bath every day,” observes a Finnish woman seated next to me on the bleachers, “but this competition—it is only for crazy peoples.”

“So why are you here?” I ask.

“I am a nurse,” she replies. “They may need me.”

There are also two paramedics and a doctor standing by. Additionally, before being allowed to compete, each contestant needs to have a clean bill of health from his or her doctor.

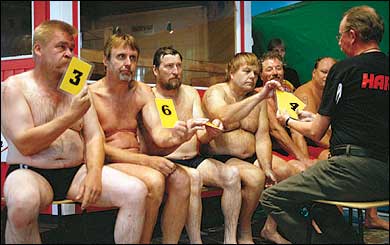

At 1 p.m. the first round begins. Five large Nordic guys and one small Japanese man, Kazuhiko Nishio, walk onstage dressed in Speedos or competition-length swim trunks (no longer than eight inches down the leg), then step blithely—rather too blithely, in my opinion—into the sauna.

From the grandstand, it isn’t easy to look into the sauna—the tiny windows are fogged and the Japanese Television Network’s nine-person crew is hogging the space. No matter. An enormous video screen gives the crowd an insect’s-eye view. It’s a strange sort of voyeurism: We can see every blob of sweat, every pained grimace, and every increasingly feeble thumbs-up in bold Technicolor.

After three minutes and 13 seconds, Kazuhiko—apparently not familiar with the concept of sisu—rushes from the sauna and disappears behind the stage, where he steps into a brisk shower. He’s soon followed by three of the five Nordic guys, who look a little like slabs of rare roast beef. This is thanks to their inflated capillaries: In a typical sauna, the blood flow through the skin can be 20 to 40 times faster than at room temperature. Here it’s probably closer to 50 times, which means the competitors’ hearts are beating at almost twice their normal rates.

Several minutes later, the last two men—Finnish, of course—exit the sauna within seconds of each other, walking so casually that, except for their scarlet, half-naked bodies, they might be a pair of boulevardiers going for a stroll. As heat follows heat, it becomes clear that Kimmo was right: The only ones not making speedy exits are the Finns.

“Hell could not possibly be hotter than that sauna,” one of the Germans tells me backstage. He had to withdraw after the first round, having made the crucial mistake of training in a dry rather than a steam sauna.

Many of these guys are suffering, but, as spectators, we’re hoping they’ll suffer more, subject themselves to higher and higher doses of heat, climb to as-yet-unachieved summits of pain. Call it the Vicarious Displeasure Principle: An ordeal, whether on a mountain, on an ice floe, or in a sauna, can be quite gratifying—as long as someone else is experiencing it.

Suddenly the Swedish spectators, instantly identifiable because they all have their nation’s flag painted on their faces, are cheering and blowing into bullhorns. Their country’s top-seeded competitor, 37-year-old Anders Mellert, has made it to the qualifying round.

“This is big surprise,” the nurse tells me. “We Finns think Swedes are . . .” She uses a Finnish word I don’t know and can’t spell.

The gentleman sitting behind me taps my shoulder. “I think the equivalent word in English is ‘candy-assed,’ ” he says.

As it turns out, Anders, candy-assed or not, lasts only 3:43 in the qualifying round and doesn’t make the semifinals, which will be held tomorrow.

Meanwhile, for Leo, the three-time world champion, the first two rounds are a piece of cake. He might as well be sitting at home in front of his TV. He remains in the sauna for 9:16 and easily qualifies for the semis.

“Last year the kiuas was only 16 kilowatts,” he tells me later. “This year it’s got two more kilowatts, so now the sauna is just right.”

Back on the video screen, Luke, the Australian, is looking as though he’d rather be Down Under, and every one of his approximately 2.3 million sweat glands seems to be in overdrive. After 4:03, he rushes out, forfeiting his slim shot at world champion.

Later, backstage, he’s interviewed by a Reuters reporter. “The door is hope,” he says. “You’re looking at it, and you say to yourself, If I don’t get out of here now, I’m history.”

“Would you do it again?” the reporter asks.

“Of course.”

THE NEXT DAY, Luke has traded his trunks for a Superman cape and matching leotards and is standing on the stage with a microphone, delivering a dramatic play-by-play of the women’s competition. Having failed to make the semifinals, he’s been asked by the organizers to put his charisma to work as emcee. He tells a joke about the difficulty of finding a phone booth in a country where everyone uses a cell phone, but the crowd doesn’t get it, and when he exhorts them to “cheer on the gals in that sauna,” almost no one cheers.

At first I think the problem is his Aussie English. Then I notice that hardly anyone, even the female spectators, is paying attention. The only rapt ones are two little kids, who start crying at the sight of their sweat-drenched mother on the video screen. I ask a Finn reading a newspaper what’s going on.

“Sauna competition is man’s sport, not woman’s sport,” he says.

“Isn’t that a bit sexist?”

“Finn people do not approve of sex in sauna. Sauna should be like church.”

“What I mean is, it seems unfair to women.”

“That may be so, but your sport of baseball is unfair to women, too . . .”

Fair enough, I think, and direct my attention back to the men, who are getting ready for their semifinals—which means guzzling electrolyte-charged sports drinks.

Yesterday’s winners—Kimmo, Leo, Timo, eight other Finns, and the Belarusan—for the most part have oversize necks, asymmetrical shoulders and hips, and a certain amount of belly flab. You could call this the survival of the least fit. Fat insulates the body not only from cold but also from heat, and the greater the quantity of subcutaneous fat, the better the insulation. In addition to their body mass, it seems the Finns, anyway, have tapped into another secret weapon: denial.

“Finnish men do not like to acknowledge pain,” Riku Jaro, the SWC’s project manager, tells me. He’s worried that one of these hulking specimens might be in agony and still not leave the sauna. It’s the sisu mentality taken to its limit.

At 12:45 p.m., as six of the 12 semifinalists enter the sauna, Luke begins singing an Australian bush song called “Get Your Gear Off.” Nobody listens. Aleaksandr, the Belarusan, doesn’t seem to be having much fun, and as he hustles toward the door, Kimmo gives him the same look that he gave me. A look that seems to say, What’s the rush?

At this point the crowd starts cheering raucously for their fellow Finns. They’re so intent on the video screen that they seem oblivious to Luke’s attempts to get them to do the wave.

Finally, at 3:30 p.m., the six finalists—Leo, Kimmo, and Timo, along with three countrymen, Markku Mustonen, Ahti Merivirta, and Raimo Tuomisto—step into the sauna one last time. All they have to do is sit and sweat. It’s hard to imagine a less vigorous test of endurance. And yet I would rather undergo a Monster Challenge Octathlon or snowboard down Everest than get punched in the face again by those blasts of steam.

Three minutes pass, then, at 3:58, Raimo makes a dash for the door. The timer hits six minutes. Kimmo, for once, looks uncomfortable, and at 7:27 he charges out of the sauna. Nearly two minutes later, Markku bolts. I wonder whether the rising tide of sweat on the sauna floor will turn this into an aquatic event.

At 10:15, Ahti departs the sauna. Now only Leo and Timo, last year’s champion, are left. Leo is bent into what looks like a meditative pose and is gazing serenely, maybe even fondly, at the Terminator. He’s taking shallow breaths in order to prevent his throat and lungs from getting seared. Both he and Timo appear to have achieved a state of mind over matter: If you don’t mind, it doesn’t matter.

Eleven minutes pass, and at 11:41 a beet-red Timo bolts out of the sauna. Four seconds later Leo comes out and raises his arms in triumph.

Backstage, I find the champ replenishing lost electrolytes with Gatorade. I give him a congratulatory handshake, then ask him what he was thinking about as he sat his way to victory.

“I was thinking about whether I’d get back home in time for a sauna.”