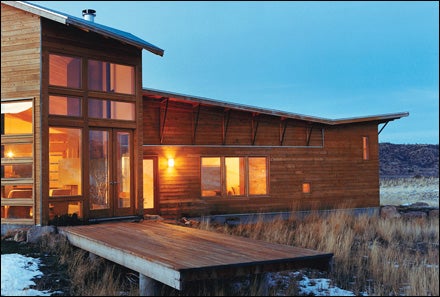

PAST A DRAB TWO-STORY Bozeman motel, its parking lot jammed with pickups and a marquee out front announcing GUN SHOW TODAY, past the pawnshop with whitewater kayaks stacked in the window, past the gingerbread-trim Victorians just off Main, past the SEE GRIZZLY BEARS, EXIT NOW! billboard on Interstate 90 and the nouveau timber mansions squatting resolutely on the bald land,a dirt road leaves the pavement and veers up a gravel drive through a keyhole in the hillside. Only then do you see it: a long, narrow house with a vaguely wavy metal roof, improbably modern, settled into its grassy hollow like a snowdrift and wearing its honey-gold siding like a skin. Surrounded by rural, ranchy Montana, it is the sleek new incarnation of sustainable architecture.

Eco-Chic House

Nave in the kitchen/greenhouse area. The cabinets are made of Douglas fir, and the counters are recycled steel (foreground) and sustainable massaranduba

Nave in the kitchen/greenhouse area. The cabinets are made of Douglas fir, and the counters are recycled steel (foreground) and sustainable massarandubaBut as incongruous as it seems, it’s not the only house of its kind around here. Its owners, husband-and-wife designers Brett Nave and Lori Ryker, have conceived half a dozen such homes in and around Livingston, about 30 miles south of Bozeman, as part of their crusade to modernize western architecture┬Śand green it up in the process. This house is their personal laboratory of sustainable building, and the boxy, wood-clad studio adjacent is their architectural HQ. Ryker, who wrote the book on modern sustainable design with 2005’s Off the Grid: Modern Homes + Alternative Energy, calls their aesthetic “contemporary vernacular,” drawing on Montana’s frontier-cabin legacy but spiffing it up with a slew of cool eco-finds like denim insulation, sunflower-seed plywood, and wheat-board cabinetry.

“One of our big goals is to make beautiful buildings and help people understand that green materials don’t predetermine a certain style,” says Ryker, whose new book, Off the Grid Homes, is due out in May from Gibbs Smith. “Yeah,” Nave translates, “we’re not talking about Earthships.”

Nave, 36, has thinning brown hair, a puckered chin, and a slow, mumbly drawl left over from his childhood in Birmingham, Alabama; he’s funny in an understated, joke’s-on-him kind of way. All of which makes him the alter ego of Ryker┬Śsunny-blond and serious┬Śwho was raised in Texas and has a master’s in architecture from Harvard. The couple met in Auburn, Alabama, more than a decade ago, started Ryker/Nave Design in 1995, and moved to Livingston three years later. In addition to her design work, Ryker, 43, teaches Remote Studio, a field program for architecturestudents that combines hands-on design with backcountry adventure to explore, as she puts it, the “intersection between nature and creativity.”

When it came time to build their own live/work compound on 40 acres of khaki wheatgrass just west of Livingston, in 2004, they chose a rutted-out old cow wallow as their construction site, deliberately building low┬Śthe 2,300-square-foot house steps down seven feet from west to east, and the roof is 18 feet tall at its highest┬Śso that the complex is all but invisible to their neighbors.

As much as the house belongs to this ridge, and to the Montana prairie wavering off in all directions, stylistically it’s a surprise: part wooden houseboat, part luxe and streamlined lean-to, part modern ranch┬ŚLincoln Log brown and as skinny as a double-wide. Nave and Ryker hunted for local, recycled, and sustainable products that were practical without being boring, innovative but not exorbitant. All told, the 4,000-square-foot project cost roughly $175 per square foot, excluding the cost of the land. Nave estimates that the national average to build green today is about $225 per square foot┬Śonly about 10 percent more than the conventional route, although where you live is a big factor.

THE HOME’S DOUGLAS fir siding was harvested from a forest 30 miles away, and the blocky master-bath wing is sheathed in untreated, cold-rolled steel, one of the most recyclable materials available. The concrete floor serves as a heat sink that absorbs sun and radiates it out at night. Nave built the soaker tub out of redwood reclaimed from a nearby barn and salvaged the greenhouse’s floor-to-ceiling windows from the old Livingston post office. The greenhouse supports citrus and succulents and, at night, the couple’s pet mallards, Thibideau and Boudreaux, who spend their days outside in a duck pond replenished by roof runoff.

But the greenest stuff is what you can’t see, like a spray-in, open-cell foam insulation called Icynene┬Śso benign, Nave claims, “you can eat it”┬Śand an elaborate water-catchment system that harvests some 14 inches of rain annually off the butterfly roof and uses it, along with gray water from both bathrooms, to irrigate a riparian garden of native grasses, willows, and aspens. Twelve solar panels provide up to 40 percent of the compound’s power on sunny days; the rest comes from the grid. And this spring, the couple plans to install a geothermal heating system that will pipe liquid heat from six feet underground, where the earth’s temperature hovers at a stable 50 degrees year-round, and warm it to 160 degrees to provide the home’s hot water and, in winter, radiant heat in the floors.

As with all sustainable strategies, the Ryker/Nave system does not run itself. Human interaction is part of the package┬Śwhich, the couple believes, makes it all the more green. “If you want to live in a passive-solar house, you have to open windows. You have to participate,” says Ryker. “Sustainable design is about creating a place that allows you to interact with the environment, not shut yourself off from it.”

Of course, it’s also about making a house that feels good inside. Even on this gray and unwelcoming day, the house is snug and inviting, with just the right combination of light and texture, scale and contradiction: exposed wood against polished concrete; airy, open kitchen funneling into a bowling-lane-narrow entrance hall bookended by tidy private alcoves; square north-wall portholes opposite floor-to-ceiling south windows streaming with sunlight.

“A professor once told me that the best place to learn architecture is where there is none,” says Nave, who credits Buckskin Gulch, a 15-mile-long sandstone slot canyon in southern Utah, as an inspiration for all his designs. “If the most beautiful space you’ve been isn’t architecture, but you can somehow translate it and then make something that begins to approach people in here“┬Śhe taps his chest┬Ś”that’s not intellectual. That’s awe.”